Fort Jackson has had a lasting impact on almost everyone who has served here. For one individual, his service changed the armed forces.

Isaac Woodard Jr. enlisted in the Army at Fort Jackson on Oct. 14, 1942. He served in the Pacific theater as a longshoreman and was promoted to sergeant. He received an honorable discharge and separated at Camp Gordon, Georgia in 1946. As he traveled back to his family in North Carolina on a Greyhound bus, his life, and the lives of countless others, were changed forever -- he was beaten and blinded by police officers in a South Carolina town.

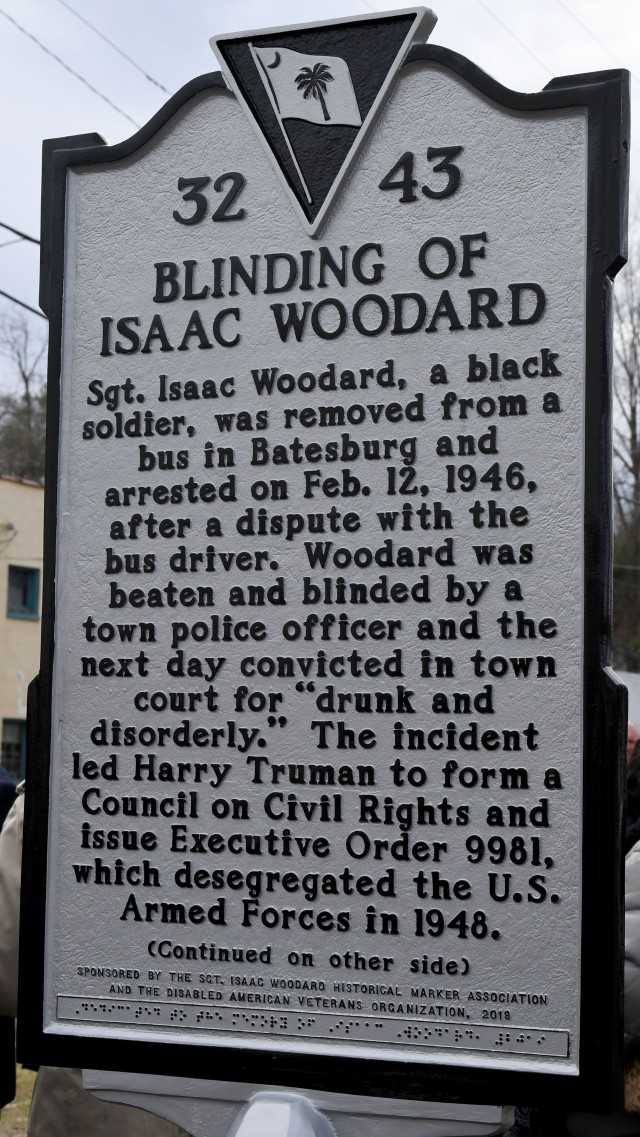

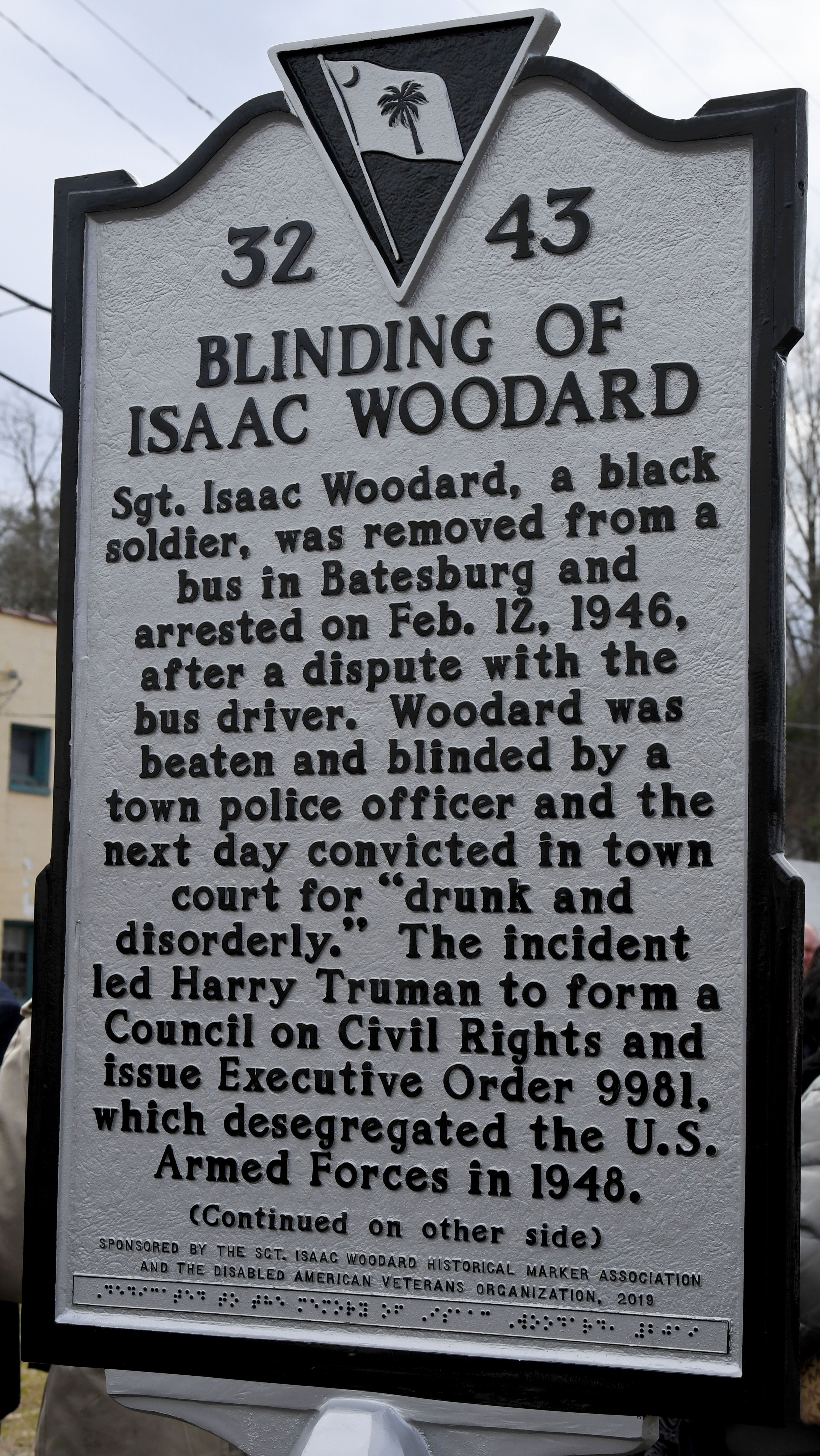

On Feb. 9, the town of Batesburg-Leesville memorialized the attack on Woodard and dedicated a plaque to acknowledge the brutal beating.

The ceremony recognized Woodard's family, and several speakers told the story of how this event changed their lives.

Brig. Gen. Milford H. "Beags" Beagle, Jr., Fort Jackson commander, talked during the ceremony about how he appreciates the sacrifice of Woodard and how far the Army has come since he was attacked.

"If I had 10 minutes with Sgt. Woodard, and if he could have his sight back for those 10 minutes, there are a few things I would show him," Beagle said.�

Those things included showing Fort Jackson's weekly graduating recruit classes of 1,000.

"He could see for himself men, with his own eyes, a fully integrated formation of men, women and a sea of skin tones," Beagle said. "In my heart, I believe he would think his sacrifice was worth (it) ... He helped build the bridge that many like me used to cross the river of inequality."

At the unveiling of the marker Batesburg-Leesville Mayor Lancer Shull, no relation to Chief Shull, apologized on behalf of the town to Woodard's 81-year-old nephew, Robert Young, of New York City.

The incident started like any other day.

Woodard asked the bus driver if he could get off the bus to relieve himself just outside of Augusta, Georgia. After a short argument, the bus driver agreed. Woodard returned to the bus and the trip continued.

When the bus stopped in Batesburg, South Carolina the bus driver contacted the local police and reported Woodard for disorderly conduct. Several officers, including the Chief of Police Lynwood Shull, removed Woodard from the bus and took him to an alley and began to beat him with their nightsticks.

While Woodard was in jail, Shull beat and blinded him. Woodard requested medical attention, but remained in the jail for two days before a doctor was finally called in. Woodard was taken to a hospital in Aiken, South Carolina, where he remained for almost three weeks. Once his family reported him missing, he was taken to an Army hospital in Spartanburg, South Carolina. Doctors determined there his eyes were damaged beyond repair.

The NAACP worked to publicize the incident nationally and Woodard's story was soon covered in major national newspapers. Orson Welles, the actor and filmmaker, advocated for the punishment of the men who had attacked Woodard.

A meeting between NAACP Executive Secretary Walter Francis White and President Harry S. Truman in the Oval Office on Sept. 19, 1946, set in motion a chain of events that would change many lives. The next day Truman wrote to his Attorney General Tom C. Clark and demanded that action be taken to address South Carolina's refusal to try the case.

Six days later the Justice Department opened an investigation into the case.

Shull and several of his officers were indicted in the U.S. District Court in Columbia, South Carolina.

Shull's trial ended after the jury deliberated for only 28 minutes and he was acquitted.

The judge who presided over the trial, U.S. District Judge Julius Waties Waring, was upset at the outcome and became a proponent of the civil rights fight and continued to push for justice and equality until he died.

Truman initiated several changes in 1948. In February he sent the first comprehensive civil rights bill to congress. In September Truman issued Executive Order 9980, which integrated the federal government, and Executive Order 9981, which banned racial discrimination in the U.S. Armed Forces.

Social Sharing