FORT MEADE, Md. -- The ferocity of the Tet Offensive, which began 51 years ago this week, surprised most Americans, including service members manning the television station in Hue, Vietnam.

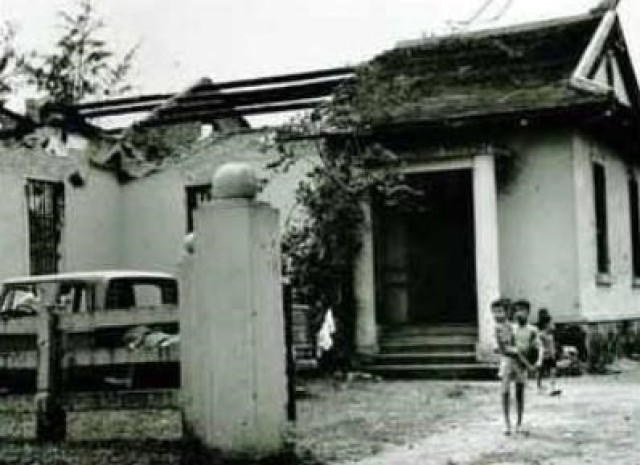

Detachment 5 of the American Forces Vietnam Network (AFVN) was located in a villa about a mile outside the main U.S. compound in Hue, in a neighborhood considered relatively safe from attack.

After the AFVN crew had signed off the air that night and settled into their billets, they heard an explosion down the street. Some of them were already asleep, but a few were still up watching fireworks through their window, since it was the first night of Tet, the Vietnamese lunar New Year.

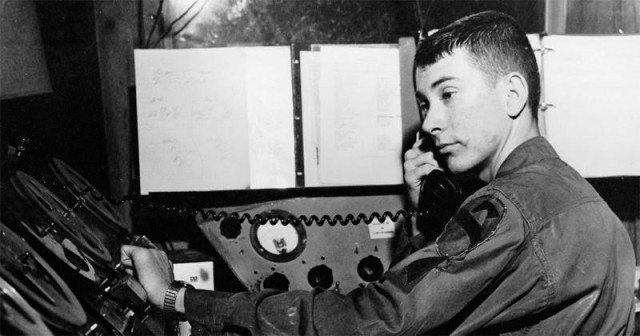

"Then the real fireworks started," said Harry Ettmueller, a specialist five and broadcast engineer at the time.

Mortars and rockets began to blast the city landscape and tracer rounds could be seen in the distance.

"It was quite a light show," said former Spc. 4 John Bagwell, a broadcaster who jumped out of bed once he heard the noise.

One mortar round hit the maintenance shed next to their TV station, which was located behind the house where the AFVN team of eight slept.

The team then pulled out their weapons: World War II carbines along with a shotgun, three M14 rifles, and an M60 machine gun that jammed after two shots.

They took up positions in doorways and windows to stop possible entry. They even handed a carbine to a visiting NBC engineer, Courtney Niles, who happened to be an Army veteran.

BATTLE FOR HUE

Station commander, Marine 1st Lt. James DiBernardo, called the Military Assistance Command-Vietnam, or MAC-V office in Hue, and was told to keep his crew in place. A division-sized force of the North Vietnamese army, along with Viet Cong guerrillas, was attacking locations all across the city.

They had even captured part of the citadel that once housed Vietnam's imperial family and later became the headquarters of a South Vietnamese division.

The NVA attack on Hue was one of the strongest and most successful of the Tet Offensive. Even though more than 100 towns and cities across the country were attacked during Tet, the five-week battle for Hue was the only one where communist forces held a significant portion of the city for more than a few days.

On the second day of Tet, the power-generating station in Hue was taken out and the telephone lines to the AFVN compound were cut. The crew became isolated.

STATION BACKGROUND

AFVN had begun augmenting its radio broadcasting with television in Saigon in early 1967. Then TV went to Da Nang and up to Hue.

The U.S. State Department decided to help the Vietnamese set up a station for local nationals in what had been the consulate's quarters in Hue. AFVN set up their equipment in a van just outside the same villa and began broadcasting to troops in May.

Hundreds of TVs were brought up from Saigon and distributed to troops. Ettmueller said he was often flown by Air America to units near the Demilitarized Zone (DMZ) to distribute them.

In January 1968, with the 1st Cavalry Division and elements of the 101st Airborne Div. moving up to the northern I Corps area of operations, AFVN decided to add radio broadcasting to the TV station in Hue.

Broadcasters Bagwell and Spc. 5 Steven Stroub were sent from 1st Cavalry to help set up the radio operation. They arrived a day and a half before Tet erupted.

16-HOUR ASSAULT

For the next five days, sporadic fire was directed at the AFVN billets, Ettmueller said. The staff members remained in defensive positions at doors and windows.

Bagwell said they were hopeful MACV would send a rescue mission for them, but by the fifth day, they were running out of food and water.

As night fell Feb. 4, the North Vietnamese launched a company-sized assault against the AFVN compound. Dozens of Vietnamese rushed the house and the Americans kept up a steady fire through the windows.

Each time the WWII carbines were fired, though, the magazines fell out and had to be reinserted, Ettmueller said. But he had an M14 and put it on full automatic.

During the assault, a young boy appeared in the window where Bagwell was on guard. The boy was trembling as he pointed his weapon at Bagwell, who hesitated.

"He shot and one bullet came close to my ear and I could hear it whiz by," Bagwell said. "The next bullet he shot came close to the other ear. I realized if I didn't kill him, he'd kill me."

He pulled the trigger on his M14 and the boy fell backward.

North Vietnamese rushed the house repeatedly during the night. Sgt. 1st Class John Anderson, the station's NCOIC, was awarded a Silver Star for manning the living room door with a shotgun to turn back assault after assault.

"He personally was responsible for inflicting deadly fire on the attacking enemy force," reads the citation, adding that Anderson held his post despite being severely wounded by enemy grenades.

At one point, a Vietnamese soldier came running toward the door with a satchel of explosives strapped around him. Ettmueller said when one of their bullets hit the soldier's satchel, it exploded, taking him out and a couple of others near him.

During the course of the night, at least three rocket-propelled grenades were fired at the house and a B40 rocket went right through the front window and hit the back wall. The wall collapsed on Ettmueller and Marine Sgt. Tom Young, forcing both men to crawl out from underneath the debris.

"They pretty much… leveled the house," Bagwell said.

BREAKOUT AND CAPTURE

By morning, the house was on fire and the AFVN crew was beginning to run low on ammunition.

They decided their best chance was to try and make a run for the MACV compound. NBC engineer Niles said he knew the layout of the city the best, so he volunteered to be the first one out the door. Bagwell was close behind him.

The plan called for both men to cross the road into a ditch so they could lay down covering fire for the rest of the team. However, Niles was fatally shot. Bagwell applied a quick tourniquet, but said it did not help much.

Anderson and others in the house saw the direction of the gunfire. After a brief pause, the seven of them ran out the door and turned in the opposite direction. They made it through a hole in the fence line and sneaked around a North Vietnamese team manning a machine gun on the second floor of a building under construction.

They made it through another hole in a fence into a small rice paddy, when they came up to the U.S. Information Services library next to a concrete wall topped with barbed wire.

There, the North Vietnamese caught up to them.

Young stepped out to lay down covering fire and was killed by automatic gunfire from the machine-gun position.

Ettmueller described the chaotic situation: "There we were, trapped. More rounds coming in; more grenades being thrown. Chickens running all over the place, jumping up in the air and flying. More rounds coming in."

Stroub was shot in the left arm and had an open fracture. He passed out, Ettmueller said. Anderson was shot with a bullet that penetrated his flak jacket and grazed his diaphragm. He began to hiccup.

As the AFVN team began to run out of ammo, the North Vietnamese closed in and captured them.

The prisoners were bound with wire and had their boots removed, and then ordered to march forward. Ettmueller helped Stroub up, but it was not long before he stumbled and fell. An NVA soldier opened fire from above with the machine gun and executed him.

SOLE ESCAPE

Meanwhile, Bagwell was left alone outside the station after Niles was fatally shot. The North Vietnamese had taken off in pursuit of the rest of the AFVN team.

Bagwell, who had been in Hue only a few days, had no idea which way to go and he was out of ammunition.

He wandered the streets, not sure what to do. "I was quite amazed with all the fighting going around that I hadn't been shot."

Then he looked down at his boot and spotted a hole. With his adrenaline pumping, he had not felt anything, but "the next thing I knew I was in pain."

Bagwell looked up and saw a Catholic church. He knocked on the door and pleaded with a priest to help him. About 100 Vietnamese civilians were already hiding in the church.

The priest insisted Bagwell change his clothes. They buried his uniform and M14 in the courtyard. Then the priest wrapped Bagwell's face in bandages.

"His idea was to make me look as much like a Vietnamese as possible," Bagwell said.

Not long afterward, North Vietnamese soldiers burst into the church looking for Americans.

"They came by and started pointing their rifles right at my face," he said. "I just closed my eyes and thought, 'there's no way they're not going to know I'm not Vietnamese.'"

But the North Vietnamese walked on past him. Bagwell was then taken by the priest up into the bell tower of the church to hide.

Other American forces, however, had been told that NVA fighters were hiding in the church, Bagwell said. So, they began to shell the church and hit the bell tower.

Part of the tower collapsed. "I just crawled out of all the mess and crawled back downstairs," Bagwell said.

The priest then rushed up to him and said, "You know, you're kind of bad luck. We need to get you out of here." He pointed across rice paddies to a light in the distance and said he thought that was an American unit.

As he crawled through the rice paddies, Bagwell said a U.S. helicopter began circling him and shining its search light down, thinking he was Vietnamese, since he had no uniform.

"Actually, during that time, I counted about 12 times that I should have been shot and killed," Bagwell said. "Six by the North Vietnamese and six by the Americans."

When the sun came up, Bagwell was near a U.S. signal unit. He took off his white shirt and put it on a stick, yelling "Don't shoot! Don't shoot! I'm an American!"

They held a gun to him and asked if he was really an American.

"You can't tell with this Okie accent?" Bagwell replied.

"Well, what were you doing out there?" a Soldier asked.

"I was with the TV and radio station," Bagwell said.

"No, I don't think so; they're all dead or prisoner," the Soldier insisted. "The only body we haven't found is Bagwell."

AFTERMATH

The North Vietnamese executed an estimated 3,000 South Vietnamese civilians in Hue during Tet for sympathizing with American forces. Bagwell said he learned that a Catholic priest was executed for hiding a U.S. Soldier in a church, and he knew that Soldier had to be him.

The prisoners of war from AFVN Det. 5 -- Ettmueller, DiBernardo and Anderson, along with Marine Cpl. John Deering and Army broadcast engineer Staff Sgt. Donat Gouin -- were forced to walk 400 miles barefoot through the jungle over the next 55 days.

For five years, they were tortured, interrogated and moved from one POW camp to another, until released from the infamous Hanoi Hilton in the 1973 prisoner exchange.

Bagwell and Ettmueller were inducted into the Army Public Affairs Hall of Fame in 2008. The Army Broadcast Journalist of the Year Award is named in Anderson's honor.

(Editor's note: Bagwell and Ettmueller were interviewed this month by phone. Retired Master Sgt. Anderson was interviewed in 1983 when he was a civilian public affairs officer at Aberdeen Proving Ground, Maryland.)

Social Sharing