SARATOGA SPRINGS, N.Y. -- "Nobody wants to talk very much about the recent battle," New York National Guard Chaplain Father Francis Duffy wrote in his diary entry in October 1918.

"It was a nightmare that one does not care to recall. Individual acts do not stand out in actions of this kind. It is a case of everybody going ahead and taking the punishment," Duffy recalled.

The punishment that Duffy's unit, the 165th Infantry Regiment -- formerly the 69th Infantry of the New York National Guard--took during the month of October 1918 was heavy indeed.

The 165th started the month with 3,564 men and officers. On October 31 the unit reported 1,908 men and officers present for duty, according to the American Battle Monuments history of the division.

The 165th, part of the 42nd "Rainbow" Division made up of National Guard units from 26 state was smack in the middle of the Meuse-Argonne offensive.

With 1.2 million Doughboys committed -- more than the 500,000 GIs who fought in the Battle of the Bulge or the 156,000 who landed in Normandy during World War II--the Meuse-Argonne is still the largest American battle in history. Twenty-seven divisions were involved in the fighting.

During the battle, which kicked off September 25 and continued until the end of the fighting on November 11, some 26,277 Americans were killed and 95,786 wounded; a casualty rate of 10 percent.

The 42nd Division began the battle after their refit from the September St. Mihiel offensive with a nearly full complement of 26,794 Soldiers and officers. One month later the division reported a strength of 20,119 on October 31.

The Doughboys were fighting not only against formidable German defenses but also dealing with difficult terrain. In the Argonne Forest visibility could be limited to 20 feet.

But for other Soldiers, like those in the 42nd Division, the fight would carry them through open fields of fire near the Meuse River where the enemy could easily spot them.

From the first artillery barrage of September 25, three weeks of difficult fighting had exhausted numerous Army divisions for little gain.

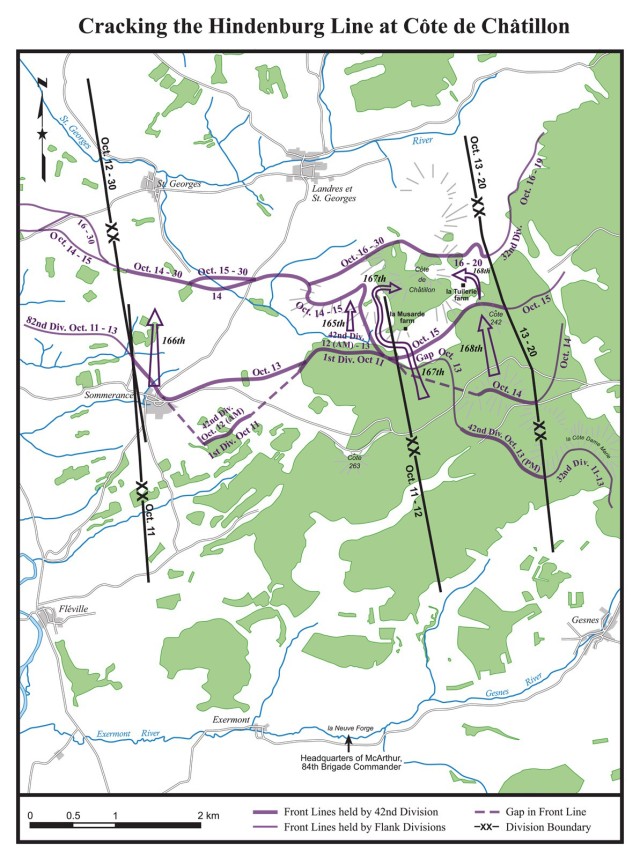

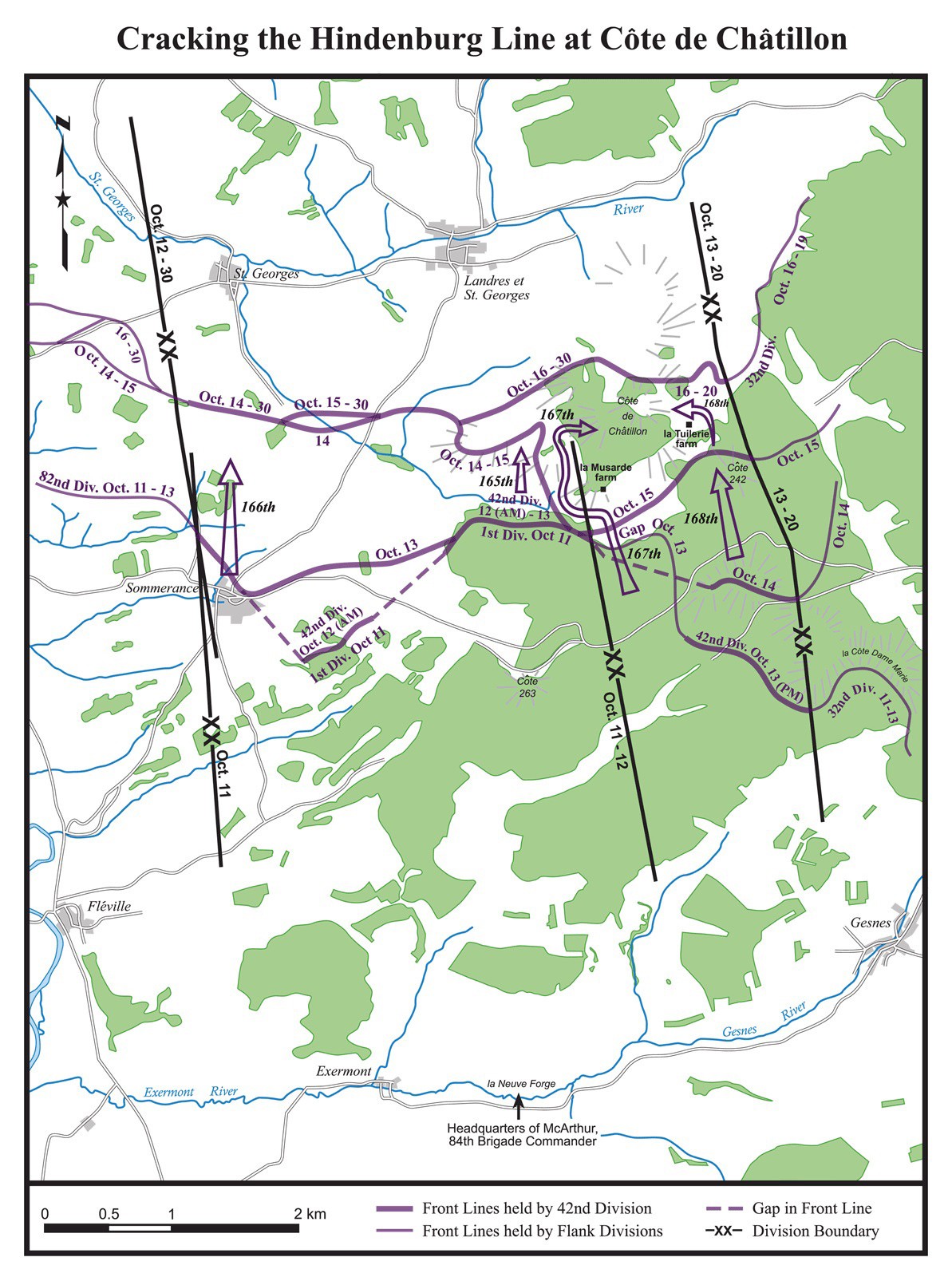

In mid-October, the 42nd Division entered the battle, bringing fresh troops to the fight. The Rainbow Division attack would cross open ground to formidable German defensive lines just three kilometers ahead.

"Our attack had to be made over open ground with the purpose of carrying by direct assault wired entrenchments," Duffy wrote of the terrain. "It was the warfare of 1916 and 1917 over again."

The objective was the German stronghold at Côte de Chatillon, part of the defensive line known as the Kreimhilde Stellung. The Rainbow would attack with all four regiments of the 83rd and 84th brigades abreast.

Maj. Gen. Charles Summerall, commander of the Army's V Corps, visited the 84th Brigade, under the command of then-Brig. Gen. Douglas MacArthur, October 13 before the attack began.

"Give me Chatillon or a list of 5,000 casualties," Summerall told MacArthur. The former Rainbow Division chief of staff replied that if they failed, the entire 84th Brigade would be on the casualty list, with his name at the top.

In two days of bloody fighting, MacArthur and his Alabama and Iowa Soldiers almost reached Summerall's casualty count, with MacArthur constantly at the front lines, ignoring the threat of shrapnel and bullets to set an example for his troops.

From the start, problems arose. A gap formed between the advances of the two brigades. The New York and Ohio Soldiers of the 83rd Brigade advanced farther, as MacArthur's regiments tackled defensive farms that drew in their manpower.

This exposed the New York regimental flank to devastating German fire.

The New York Soldiers of the 165th Infantry found themselves facing machine gun and mortar fire from two sides, trapping them short of their objective.

"The situation was a stalemate," Duffy noted in his 1919 Father Duffy's Story. "We had made an advance of three kilometers under desperate conditions, but in spite of our losses and sacrifices we had failed to take our final objective. Well, success is not always the reward of courage."

Infantry regiments lost some two-thirds of their fighting strength in the initial 24 hours of fighting.

The 165th Infantry, for example, crossing open ground and facing flanking fire, had only 186 Soldiers remaining in its 1st Battalion, 480 in the 2nd Battalion, and 496 in the 3rd Battalion.

Consolidating after the first day, MacArthur devised a plan for a night attack using only the bayonet to seize Côte de Chatillon. The belief was that enemy machine guns would not be able to locate Doughboys without the flash the of their rifle fire.

The Soldiers of the Alabama and Iowa regiments were spared the daring assault when Maj. Gen. Charles Menoher, the division commander, canceled the operation in favor of a renewed artillery barrage the following morning.

General John J. Pershing, commanding the entire American Expeditionary Force, noted the difficulties in the American advance in the 1923 Records of the Great War by Charles Horne.

Divisions were fighting "to the limit of their capacity," Pershing said. "Combat troops were held in line and pushed to the attack until deemed incapable of further effort because of casualties or exhaustion."

By October 16th, with German forces spent almost as much as the Doughboys, the Rainbow Division's 84th Brigade reached the crest of Chatillon and held it against German counterattack, allowing the division's line to reach its objective.

With Company M of the Alabama 167th Infantry Regiment was Private Thomas Neibaur, a replacement National Guard Soldiers from Sugar City, Idaho. When Neibaur's fire team moved around a hilltop objective to provide enfilading fire, his element met a German counterattack.

"I looked up..I saw about 40 to 45 Germans coming up directly toward me," Neibaur recorded after the war. "I quickly turned my automatic rifle on them and fired about fifty shots."

Wounded three times in both legs, his two teammates killed, Neibaur fought off the counterattack with his automatic rifle until only 15 enemy were in close range. Neibaur killed four Germans and captured the remaining eleven. He received the Medal of Honor for his actions.

Relieved on October 18, the Rainbow Division was not quite through with the campaign. Refit with replacements and equipment, the division was back in the line by November 5, pursuing retreating German forces.

"The retreating Germans were almost always only about an hour ahead of us," said Lawrence Stewart, a medic in the Iowa 168th Infantry Regiment in his 1923 account, Rainbow Bright. "The rear guard put up a fight, but the columns in advance gave a lifelike imitation of a foot race."

In the final hours of the war, the American objective was the French city of Sedan, where France had surrendered to Germany in 1871, ending the Franco-Prussian War. With the 42nd and 77th Divisions under the command of I Corps and the 1st Division from V Corps all attacking towards Sedan, Maj. Gen. Summerall allowed his 1st Division to cross the corps boundary in an effort to encourage speed in taking Sedan.

But crossing boundaries has its own risks for confusion, traffic and friendly fire when units intermix.

On the night of November 6, with Rainbow Division Soldiers of the 165th Infantry in the outskirts of Sedan at Wadlaincourt, a patrol of the 1st Division led by a lieutenant detained an odd-looking prisoner.

"All he saw in the gathering dusk was an important looking officer walking around, attired in what looked like a gray cape and a visored cap with a soft crown, not unlike those the Crown Prince wore in his pictures," wrote Raymond Thompkins in his 1919 The Story of the Rainbow Division.

Capturing the odd-looking officer near the front, "they got him back to a brigade headquarters of the 1st Division, before Brig. Gen. Douglas MacArthur, commanding the 84th Brigade of the Rainbow Division, could convince them that it was himself and not an officer of the German Army."

The race to Sedan was set aside the following day when French forces liberated their city. With American forces across the Meuse River, Germany began to seek peace terms November 8.

As Rainbow Division Soldiers reorganized to continue the allied attack, word spread through the lines that fighting would end at the 11th hour of the 11th day of the 11th month. The Great War was over.

During the World War I centennial observance the Division of Military and Naval Affairs will issue press releases noting key dates which impacted New Yorkers based on information provided by the New York State Military Museum in Saratoga Springs, N.Y. More than 400,000 New Yorkers served in the military during World War I, more than any other state.

Social Sharing