WASHINGTON -- Sergio Rosas sat alone in the bedroom of his home in Raeford, North Carolina. The sergeant had just decided to leave the Army and the Soldiers he considered to be his second family.

At the time, he was recovering from a difficult surgery. Building his body back to meet the Army's physical fitness standards seemed like a daunting task.

The five-inch scar above his forehead served as a grim reminder of the pain he endured and the depression that swept over him as a result of his surgery. Unable to exercise and out of shape, he feared he might not return to the physically fit, mentally tough Soldier he had been during deployments to Afghanistan and Kuwait.

He felt like a shell of his old self.

Six months before, doctors at Duke University Hospital removed an abnormal vein growth on the top of his skull. After enduring a two-part surgical procedure, he faced a difficult recovery.

In the weeks that followed, Rosas suffered from spells of dizziness. Headaches plagued him daily.

Now, 20 miles from the bustle of Fort Bragg in his one-story home, he lit a candle, unsure if he had might the right choice to leave the service. He pulled out the purple emblem with a photo of Jesus Christ. Like he and his family had done so many times in their small residence in Lima, Peru, Rosas knelt, bowed his head, and began to pray.

A LIFE LEFT BEHIND

To Victor Rosas, his younger brother Sergio would always be known as "Chocho," the baby-faced boy who tagged along with him on the streets of Lima. There, Sergio's family lived in the back of his parents' dusty hardware store, where they sold tools, bathtubs and toilets.

The two brothers would often walk or take the bus together to the markets and carnivals. Chocho followed Victor to gatherings at friends' houses. Clutching his younger brother's hand, Victor would bring him to the local shoe store each year, where Sergio would try on different pairs of shoes until he found the perfect fit.

"He was like my son," said Victor, who is 12 years older than Sergio.

Lima, located along South America's rugged western coastline, lies in a desert strip between the Andes Mountains to the east and the Pacific to the west. Sergio and Victor lived there with their parents and three other siblings before immigrating to the United States.

Known for its rainforests and its stunning Mayan ruins, Peru houses one of the world's most colorful cultures. But that cultural allure hid the ugliness of political violence in its capital.

In the late 1980s and early 1990s, protesters turned Lima's downtown district into a hotbed of violence. Victor, a teenager at the time, remembers when terrorists from the communist activist group Shining Path bombed a local bank in his neighborhood.

In 1990, two years before the Rosas family left for the United States, more than 3,000 politically-related murders had been reported, and the economy was devastated by government corruption. The Rosas family felt its impact. At times they did not even have running water.

"It was very alarming for us," Victor said. "We (said) 'we can't live here.'"

In October 1992, Victor and older sister Monica left Peru for the United States. It would be the first time Sergio would be separated from his older brother, whom he idolized. In December of that same year, Sergio, his brother Omar, and his mother Rosa left for the U.S. The family reunited in New York City.

Within six months of arriving in New York, the family departed for the busy Miami, Florida, suburb of Hialeah, to meet up with Sergio's father, Sergio Sr., who had traveled directly from Lima to Miami.

At that time, both of Sergio's parents and three of his four siblings had made it to the United States. His oldest sibling, Veronica, wouldn't arrive in the U.S. until 2000.

In Florida, the family's life began to move quickly.

In Miami, Sergio's parents started a flower business to support the family. But that meant long working hours for his parents and Victor. The fond childhood days of family dinners and walking with his brother to the market had ended.

Victor, then 20, attended college courses and spent much of his time helping his parents sell flowers. He'd wake before the sun rose and leave the family's two-bedroom flat to pick up a shipment of flowers at the nearby Miami International Airport. Then he would drive to different corners of Hialeah where they would walk the streets until darkness fell. They sold roses from shopping carts they pushed along city streets.

Meanwhile, Sergio, at 8 years old, began taking classes at James H. Bright Elementary School in Hialeah. With his parents and older brother away, he learned to wake up for school and do his classwork on his own.

"He was thinking on his own," Victor said. "He was kind of forced to do that. He matured really fast -- faster than, I think, anyone in the family."

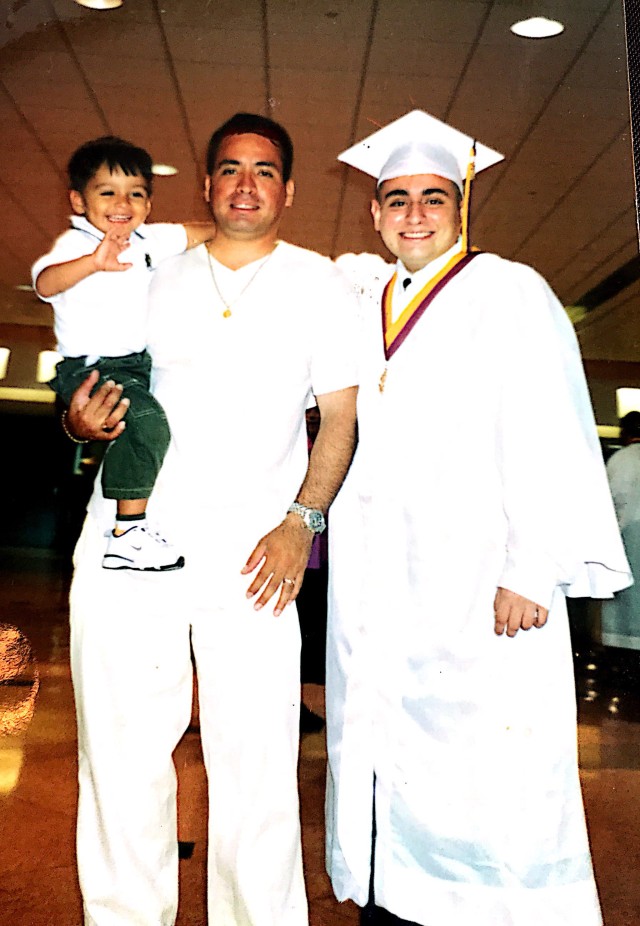

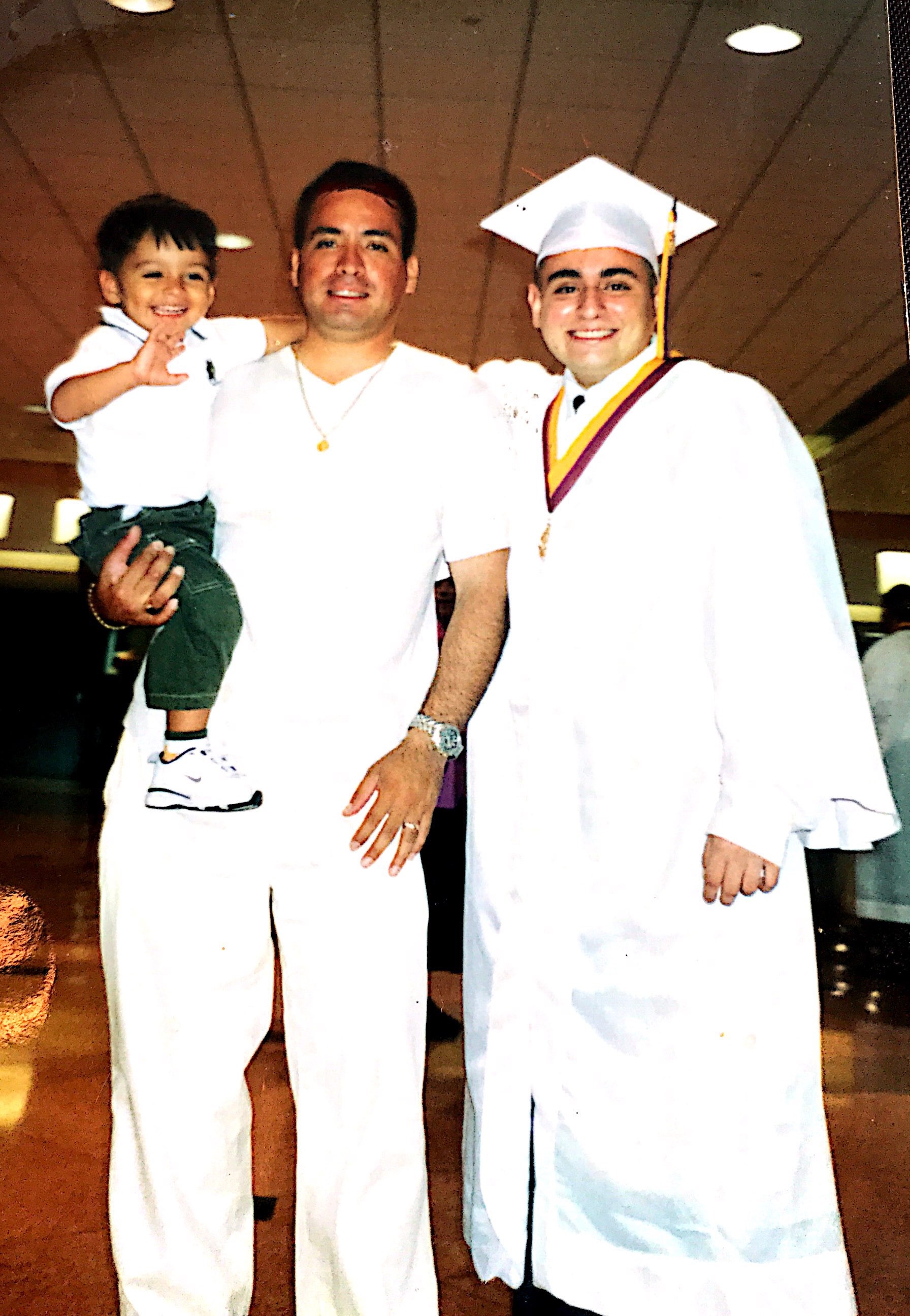

By the time Sergio graduated from Barbara Goleman Sr. High School in 2002, he had begun helping his mother with the flower business.

Like his older siblings, Sergio sold roses out of the family van. He helped grow the family business, appropriately named "Rosa & Rosas" and helped his mother move operations into a local shop located in the industrial district on the northwest side of Hialeah.

But he admittedly lost his way in finding a career path. Under the encouragement of Victor, who had already joined the Army and who still serves today as a warrant officer, Sergio also decided to serve his new country.

SIGNS OF FAITH

Weeks before Sergio left for basic training at Fort Sill, Oklahoma, his mother gave him a small embroidered emblem of "Señor de los Milagros" or "the Lord of Miracles," a portrait sacred to Peruvians.

"This belonged to your Uncle Victor," Rosa said to her son in Spanish, placing the emblem in his hand. "Take it with you. It will protect you."

The elder Victor Rosas had served in the U.S. Army in Vietnam during the 1970s and had carried the emblem with him into combat. Sergio took it with him when he joined the Army.

According to lore, an African slave painted a portrait of Jesus Christ in the 1600s. In 1655 a devastating earthquake rocked Lima, destroying much of the city. Many buildings fell, but the small adobe hut with the painting remained unscathed. Another quake struck the city in 1687, and once again the portrait survived.

Today, the Church of Nazarenas, an old cathedral in the heart of Lima's downtown, houses the portrait, which Peruvians believe has healing powers. Every October, thousands flood the downtown streets in a procession carrying the Shrine.

"I still maintain my faith," Rosas said. "Even through the good times and the bad times."

In 2009, Rosas boarded a plane from Miami to Fort Sill, Oklahoma.

It was there, after receiving the close-shaved military haircut during basic training, that he first noticed a bump protruding on the top of his head. It wasn't until later, however, when stationed at Joint Base Lewis-McChord, Washington, that doctors told Rosas he had an "arterial abnormality," and suggested surgery.

That surgery wouldn't come until the end of a year-long deployment to Kuwait. During that deployment, Rosas was assigned the grim task of reporting casualties and logging their details. Soldiers tasked with this duty would sometimes run across a name of a Soldier they had served with. Rosas said he remembers that a Soldier in his unit broke down in tears after reading the details of one such report.

"It could affect you dramatically," Rosas said.

The symptoms of that arterial abnormality grew stronger for Rosas, he said. The headaches became more frequent and intense. Finally, he sought the medical help needed to remove the swelling.

In July 2016, doctors at Duke University Hospital performed surgery to untangle the swollen veins and detach them from his skin.

SAVED

Two days after his head surgery, Sergio awoke in a daze with his pillow soaked in his own blood. Sergio turned to his mother and niece, who still lay asleep in his hotel room near Duke University. Instead of waking them, he picked up the Lord of Miracles emblem from the nightstand next to him, held it close to his chest and began to say a prayer.

"Spiritually," Sergio said, "I felt like something woke me up."

Minutes later, he woke his mother and niece. Wearing plastic gloves, they carefully unraveled his bandages. They cleaned around in the incision. They replaced the gauze and wrapping, tying the binding tighter, and drove him to the emergency room.

Doctors said recovery would take up to three months. During that recovery, he would not be able to work full days and had to refrain from strenuous physical activity. The stitched-up incision caused radiating pain in his head.

"Those kinds of things put me down," Rosas said. "Do I really want to go through this?"

During Sergio's recovery, Rosa sat with him and told him stories of his homeland on South America's western coast. They talked about the plane ride to New York City, the months they spent living in a tiny two-bedroom apartment in Brooklyn to gain their work visas, and the years they spent peddling flowers on street corners in Miami.

She reminded him of how far he had come from the small boy who followed his brother around; how he had helped grow her business from peddling flowers on street corners to becoming a respected local shop owner.

She told him how proud he had made her.

Others encouraged him as well, including his first sergeant, platoon sergeant, his girlfriend Karlene Gacita, and of course his brother Victor.

"It was a nucleus of support," Rosas said.

And in his darkest moments, Sergio turned to a higher power, clutching the purple emblem symbolizing the painting Peruvians hold sacred.

RECOVERY

For six months, Rosas remained on limited duty. He could not engage in strenuous physical activity or even run.

Rosas did all that he could to speed his recovery. He ate healthy. He drank a green veggie shake in the mornings, and ate mostly broccoli, quinoa and boiled chicken. He later began taking brisk walks.

Out of breath running at Fort Bragg's Hercules Fitness Center, Rosas was shocked when he could no longer run a mile. He could not perform a single pull-up.

"I wanted to push myself," Rosas said, "but I couldn't."

Each day Rosas tried to endure a bit more, but it proved to be a tough slog. The sergeant started with walking long distances, and slowly began to jog.

"I would try to run," Rosas said. "But I would feel my head moving."

When his recovery seemed in doubt, he would light a candle in his room and put his faith in the Lord of Miracles.

"Sometimes I would have bad days where my head would hurt," Rosas said. "I would pray just to take the pain away."

Then, in the middle of his recovery, and when he was at his lowest -- when he'd decided to leave the Army -- his first sergeant at Fort Bragg delivered promising news: he had been chosen to interview for a position at the Pentagon, working for Vice Chief of Staff of the Army Gen. James C. McConville.

Rosas talked over the position with Victor and his family. CW4 Jamie Alonso, his supervisor in the First Sustainment Command, told him that the Army could use more leaders like him.

RETURNING TO FORM

By the time Rosas left Fort Bragg, he was running farther distances. A mile turned into two. Two became four. It would be nearly a year by the time Rosas inched closer to equaling his best two-mile time: 14:19 seconds. After overcoming the hurdle of doing a pull-up again, he began to perform push-ups and sit-ups at a greater pace.

"I had to be mentally strong," Rosas said. "I had to remember why I joined the Army."

Two months after beginning his new duties as an administrative noncommissioned officer for the Army's vice chief of staff, he took his first physical training test since his recovery. He passed easily.

PENTAGON DUTY

In the hallways of the Army headquarters at the Pentagon, the Soldiers assigned must remain diligent and courteous. At any moment, a four-star general or Department of Defense official may walk into their office.

In the Pentagon, Rosas works in an office that serves two Army senior leaders. On one side of the room, a small hallway leads to the office of the Vice Chief of Staff. On the other side, another hallway leads to the office of Chief of Staff of the Army Gen. Mark A. Milley.

Rosas greets each visitor to the office with a spirited hello and an attentive gaze. He said he learned the value of customer service watching his parents serve patrons at their hardware store in Lima.

"He is of sound mind that his condition will not hinder his position in life," said CW5 Yolondria S. Dixon-Carter, assistant executive officer to the Vice Chief of Staff of the Army.

Working in the VCSA's office invigorated Rosas. And he recently earned a prestigious honor in his career field: being named the Adjutant General Non-Commissioned Officer of the Year.

Rosas has also earned his bachelor's degree in human resources, and plans to pursue a graduate degree. Eventually, he said, he will try to join his brother in the warrant officer ranks.

Sergio's success doesn't surprise his older brother.

"He had the potential even before he joined the service," Victor said. "(He's) very committed to do any task. Whatever he's being told, he's going to do it. That's the Sergio I know."

Social Sharing