FORT JACKSON, S.C. (June 11, 2015) -- The drill sergeants in training lay prone in pairs in the predawn light, aiming at tiny silhouettes two meters away, their laser optics bouncing about like red fireflies.

Pop! . . . Pop! . . . Pop-pop! their M-16s hiccupped, forcing through the air invisible sound waves that shook stomachs and legs, and assaulted the tiny hairs of each Soldier's inner ear, bending

them, perhaps breaking them.

These are the sounds drill sergeants hear every day, continuously as they instruct Basic Training Soldiers on how to fire their weapons. Such constant and prolonged exposure to noise can damage hearing permanently -- insidiously but as profoundly as an explosive burst in wartime.

And that is why, after shooting M16s at Range 1 on Tuesday, a handful of drill sergeant candidates also threw back slugs of an orange liquid containing D-Methionine, which initial tests have shown can alleviate or even repair noise-induced hearing loss if taken before noise occurs or within 24 hours after. Candidates at Fort Jackson's Drill Sergeant Academy are test subjects in Phase 3 clinical trials that must be completed before the substance can be released publicly.

"The Drill Sergeants School has been superb" in its contributions to the blandly named Army Research Project, said Kathleen Campbell, an audiologist and researcher from Southern Illinois University-Springfield who developed and patented the liquid. "I cannot believe the level of their cooperation.

"Not only are these troops, they're model Soldiers" working to spare colleagues from the effects of noise poisoning.

"(Noise) is a toxin," Campbell said. "It absolutely is a toxin."

And hearing loss "is an invisible disorder" that occurs more often -- and costs more to treat -- than post-traumatic stress disorder, as well as being one of the most common reasons Soldiers cannot be redeployed to war zones.

The Defense Department has given Campbell and her team of researchers $2.5 million to administer Phase 3 of testing prescribed by the federal Food and Drug Administration.

'We have to do better'

The pop! of an M16 registers at about 155 decibels, said Elizabeth Bullock, a research nurse with the Army Research Project. Foam ear protectors shave 25 to 30 decibels from that, leaving the count still higher than the 85 decibels at which damage occurs.

"Even with ear pros, you're 40 decibels above what's safe," Bullock said. "And that doesn't even account for what's going through the skull directly" and to the delicate hairs of the inner ear.

"So we have to do better. This (M16) is the kindest weapon we have. Everything else is noisier."

Staff Sgt. Tyler Durden of the Joint Readiness Training Center at Fort Polk, Louisiana, already experiences tinnitus, a ringing in the ears caused by hearing damage. He was a ready volunteer for the trials because "this is a huge opportunity to make things better for everybody" subject to hearing loss.

On Tuesday, he slugged back a dose of the orangish liquid, whose taste he said reminded him and other waggish Soldiers of the excretions of an animal none of them is likely to have encountered. Even so, Durden did not request the proffered water, juice or peppermints nurses had brought with them to alleviate the taste of the medicine.

Sgt. Hollie Tyson of the 299th Brigade Engineering Battalion, 1st Brigade Combat Team, 4th Infantry Division at Fort Carson, Colorado, grimaced slightly after downing her little brown bottle of meds.

She said she couldn't guess whether she had been taking the actual medicine or a placebo -- the study is randomized and double blind, and doses are titrated according to each Soldier's weight. Even Campbell does not know who receives which. The data from her study go to Yale, to keep the drug's performance data "at arm's length" from its inventor.

"I've compared (its effects) with others to see what our bodies go through," Tyson said, "but it all seems the same."

The science behind the studies

D-Met is an amino acid/micronutrient that messages replacement electrons to the atoms of degraded hair cells. The substance occurs naturally in such foods as yogurt and cheese, but a person would have to eat 4? pounds of cheese twice a day to get the effect of one swig of liquid.

The substance also appears in almost every form of animal "chow."

Campbell wants to develop a pill, which would be easier for Soldiers to carry on the battlefield and might alleviate the noxious taste some experience when they swallow the liquid. But developing a pill form, she estimates, would cost about $1 million. Plus, she would need a licensure partner, someone willing to chart a new path and something she does not yet have.

Campbell has been testing D-Met in humans for 10 years. In the lab, she had used chinchillas, whose ears have the same construction as humans'.

Because she is so cautious about noise -- and knows what it can do -- Campbell carries ear protection with her everywhere.

Why Fort Jackson?

In Phase 1 of testing, Campbell worked with a small biotech company that since has dissolved. Researchers there reported no adverse reactions. Because hers is the first treatment for hearing loss to come before the FDA, Campbell must help develop her own testing procedures -- the FDA has no protocol to which it can refer.

In Phase 2, she tested it with patients who had head or neck cancers, patients prone to chemotherapy-induced hearing loss. Again, researchers cited the drug's effectiveness and reported no adverse effects.

Phase 3 is the last phase of testing, a phase Campbell worried for a time she would not be able to complete. She needed test subjects who regularly experienced noise bombardment, but she could not ethically induce it herself.

After searching for 10 years, she found the Army by chance: an Army audiologist who met Campbell at a conference suggested that Soldiers would make willing and compliant subjects.

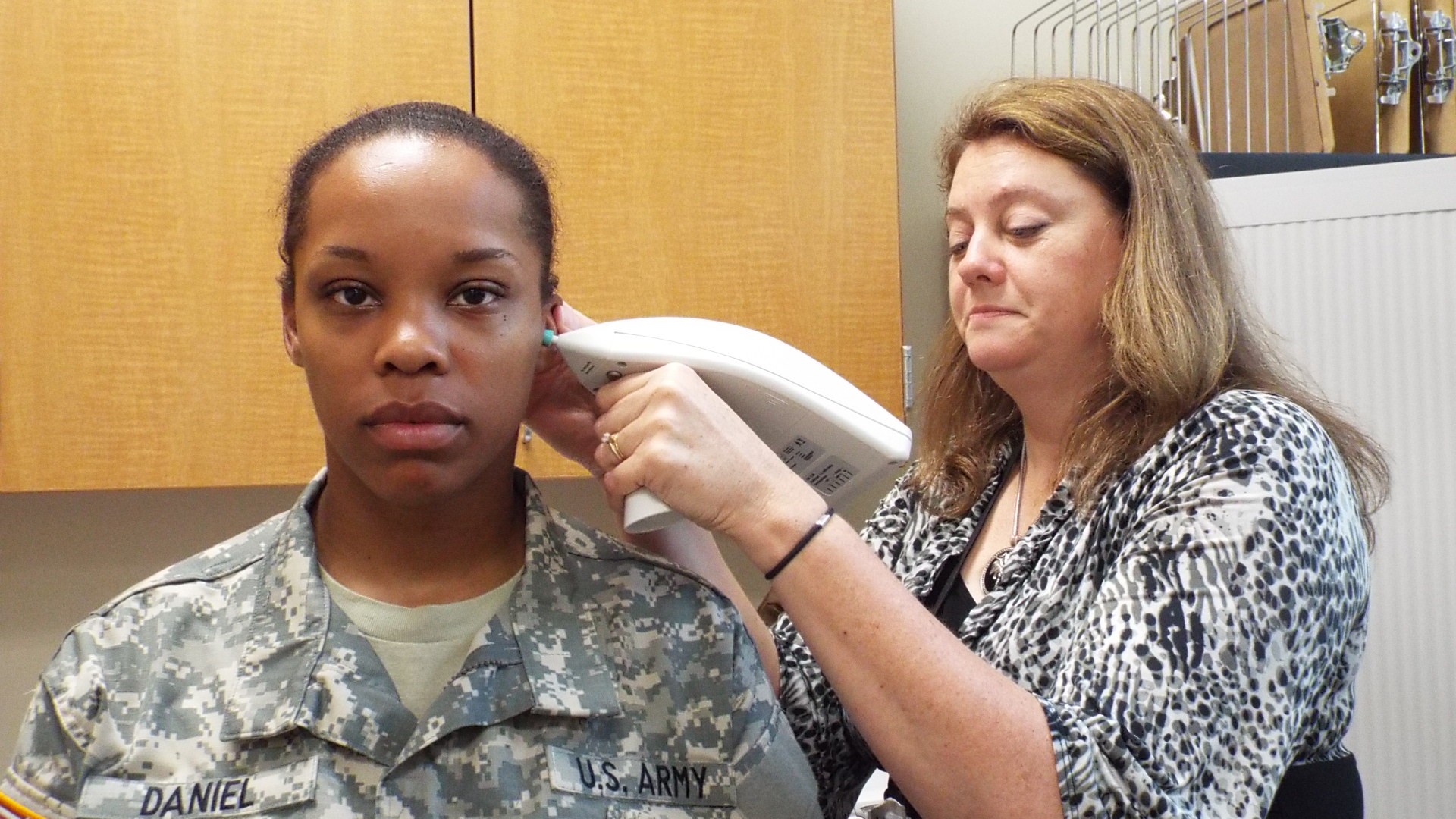

And so she is at Fort Jackson, where she and her two research nurses use the former break room of the Drill Sergeant Academy to administer hearing tests and questionnaires that ask about potential side effects, and linger at the shooting range to administer D-Met at chow time.

All of the test subjects are volunteers who rotate into and out of the DSA. So far, Campbell's team has tested approximately 200 subjects. It's aiming for 600 and does not know how long that will take to accomplish.

Social Sharing