Timeline

Loyalty, Service & Sacrifice

During National Hispanic Heritage Month, recognized from September 15 to October 15, we pause and reflect on our shared history as Americans and celebrate the rich mosaic of people and cultures who build and strengthen our Army and our nation.

Hispanic Americans possess a unique and storied history in the U.S. Army — serving and fighting in almost every war since our nation's birth. In total, 44 Hispanic American Soldiers have been awarded the Medal of Honor, the country's highest military decoration.

The timeline below provides a chronological overview of Hispanic American contributions to U.S. Army history. Although it is not a full account of every person and event, the highlights provide insight into each era.

CIVIL WAR

Overview

Like other ethnic groups of Americans, Hispanics were divided in their loyalties, fighting heroically for both the Union and Confederate armies. Most Hispanics were integrated into the regular Army or volunteer units, although some served in predominantly Hispanic units with their own officers. Hispanics were especially instrumental in protecting the Southwest against Confederate advances, most notably in California, Arizona and New Mexico.

At the outbreak of the conflict, some 1,000 Hispanics joined the regular Army. A short time later, the New Mexico Volunteers, a mostly Hispanic militia unit, joined the Union cause. The 2nd Regiment, commanded by Col. Miguel E. Pino, a Mexican American, fought in the battle of Valverde in February 1862, and at Glorieta Pass a month later, helping to defeat a Confederate invasion of New Mexico. Later in the war, the Union raised several companies of mostly Hispanic cavalry in Texas and California. Those units guarded supply trains, fought against bands of Confederate raiders, and participated in the Union's limited campaigning in the southwest. Hispanic American units formed during the Civil War were not retained after the cessation of hostilities. Hispanics continued to serve in the Army, but were assimilated into it in much the same manner as European immigrants had been decades earlier.

Gen. Alexander Webb, on white horse, leads the Union attack. Art is part of the Gettysburg Cyclorama painnting by Paul Philippoteaux. Photo courtesy of the National Park Service.

Joseph De Castro: First Hispanic American Medal of Honor recipient

Joseph De Castro, born in Boston, Massachusetts, was the flag bearer of the 19th Massachusetts Infantry and fought at Gettysburg. On July 3, 1863, the third and last day of the battle, he and his regiment faced the fury of Pickett’s Charge — the bloody Confederate infantry assault against the Union positions on Cemetery Ridge.

Under intense fire, De Castro charged forward and captured the enemy flag. He then broke through the lines and without saying a word handed the prize over to Col. Arthur Devereux before rushing back into the fight. It was an emblematic moment in one of America’s most epic battles.

On December 1, 1864, De Castro became the first Hispanic American to be awarded the Medal of Honor.

SPANISH-AMERICAN WAR

Overview

On February 15, 1898, an explosion of unknown origin sank the battleship U.S.S. Maine in the Havana, Cuba harbor, killing 266 of the 354 crew members. The sinking of the Maine incited United States’ passions against Spain, eventually leading to a naval blockade of Cuba and a declaration of war.

Ostensibly on a friendly visit, the Maine had been sent to Cuba to protect the interests of Americans there after riots broke out in Havana in January. An official U.S. Naval Court of Inquiry reported on March 28 that the ship, one of the first American battleships and built at a cost of more than two million dollars, had been blown up by a mine without laying blame on any person or nation in particular, but public opinion in the United States blamed the Spanish military occupying Cuba anyway. Subsequent diplomatic communications failed to resolve the matter, leading to the start of the Spanish-American War by the end of April.

The conflict ended with Spain losing most of its overseas empire and the U.S. emerging as a world power. After only a few months of fighting and a series of American victories in the Caribbean and the Pacific, the Treaty of Paris was signed on December 10, 1898, officially ending the war. As a result of the treaty, Cuba received its independence and Puerto Rico and Guam were ceded to the U.S. The U.S. also purchased the Philippines from Spain for $20 million.

Several thousand Hispanic volunteers, mostly from the Southwestern United States, fought with distinction in the U.S. Army during the Spanish-American War.

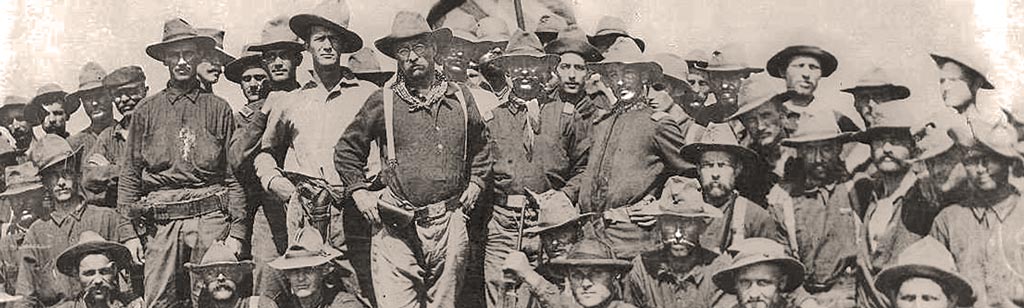

Col. Theodore Roosevelt and his Rough Riders are shown at the top of the hill, which they captured, during the Battle of San Juan, 1898. Photo by William Dinwiddie, courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Capt. Maximiliano Luna was one of the Rough Riders' four captains and the highest-ranking Hispanic in the famous regiment. He served in all the major battles fought in Cuba and played a key role as a translator when the Spanish surrendered.

Photo courtesy of the Donald Deesen Collection, Southwest Center for Research, University Libraries, University of New Mexico.

Capt. Maximiliano Luna

Originally from New Mexico, Capt. Maximiliano Luna fought in the Spanish-American War as the only Mexican American officer in the 1st U.S. Volunteer Cavalry — better known as the Rough Riders, famously commanded by the future 26th president of the United States Theodore Roosevelt.

While serving in the Philippine-American War, Luna drowned while crossing the Agno River on the island of Luzon on November 18, 1899. His name is the first listed on the Rough Riders Memorial in Section 22 of Arlington National Cemetery.

WORLD WAR I

Overview

At the beginning of World War I, the U.S. Army had approximately 200,000 active personnel. An act of Congress was passed in 1917 to obtain needed manpower, and the Hispanic community was eager to serve its country. They included both native-born Soldiers, mostly of Mexican descent, new immigrants from Latin America, Mexico, Cuba and the newly acquired territory of Puerto Rico. In May 1917, two months after legislation granting United States citizenship to individuals born in Puerto Rico was signed into law, and one month after the United States entered World War I, an authorized unit of volunteer Soldiers mustered and headed to the Panama Canal Zone.

After the end of the Spanish-American War in 1898, Puerto Rican Soldiers had served as volunteers in the 1st Puerto Rican Infantry Battalion and the 2nd Puerto Rican Mounted Battalion. From 1899 to 1917, the 1st and 2nd Battalions reformed into the Puerto Rican Regiment of Infantry, and the first Puerto Rican Soldiers became commissioned officers in the U.S. Army. After the United States entered World War I on April 6, 1917, the Regiment of Infantry was sent to the recently completed Panama Canal to prevent the Central Powers from using it to fight the Allies. U.S. Army policy at the time restricted most segregated units to noncombat roles, even though the regiment could have contributed to the fighting effort. Besides the infantry regiment, 18,000 other Puerto Rican men and women served in the armed forces throughout various fighting and support units.

At the end of World War I, the Army reduced in size to pre-war levels. During the drawdown, the Puerto Rican Regiment of Infantry was re-designated the 65th Infantry Regiment of the regular U.S. Army. The regular Army differed from the state volunteers and militias that made up the units before World War I as it was a full time, professional force. Since the 65th was re-designated into the regular U.S. Army, its officers automatically received American citizenship regardless of birthplace.

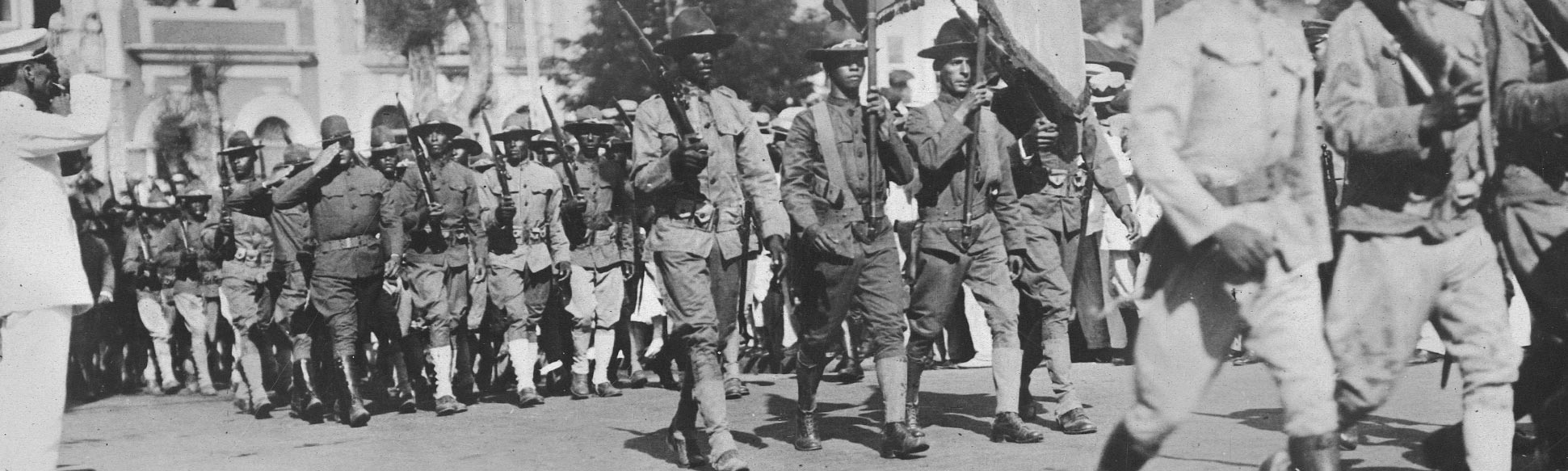

Puerto Rican Soldiers of the 375th Regiment Infantry pass before the grand stand at the Liberty Day demonstration in Puerto Rico. Photo by Underwood and Underwood, courtesy of the National Archives.

First Company, 2nd Puerto Rico Mounted Battalion. Photo courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Puerto Rican Volunteer Units

Puerto Rican Soldiers served as volunteers in the 1st Puerto Rican Infantry Battalion and the 2nd Puerto Rican Mounted Battalion. From 1899 to 1917, the 1st and 2nd Battalions reformed into the Puerto Rican Regiment of Infantry, and the first Puerto Rican Soldiers became commissioned officers in the U.S. Army. After the United States entered World War I on April 6, 1917, the Regiment of Infantry was sent to the recently completed Panama Canal to prevent the Central Powers from using it to fight the Allies.

Pvt. Marcelino Serna poses for a photo in his uniform. Courtesy photo.

Mexican Americans serve with distinction in WWI

Pvt. Nicholas Lucero of the 23rd Divsion and originally from Albuquerque, New Mexico received the French Croix de Guerre for destroying two German machine gun positions and for keeping constant fire on enemy positions for more than three hours.

Pvt. Marcelino Serna was an immigrant from Mexico who moved to El Paso, Texas, during World War I. Serna volunteered to join the Army and declined to be discharged when it came to light that he was not a U.S. citizen. He shortly thereafter went to war in France.

On Sept. 12, 1918, while acting as a scout, he followed a German sniper back to a trench. Alternating between throwing grenades and firing his rifle — all the while changing positions to deceive the enemy into thinking they were under attack from a larger group — Serna killed 26 and captured 24 enemy soldiers single handedly.

On Nov. 7, 1918, just four days before the armistice, a sniper shot Serna in both legs. During his recovery at a French hospital, Gen. John J. Pershing, the commander-in-chief of the American Expeditionary Forces, presented Serna with the Distinguished Service Cross, the second-highest American combat award. Serna was the first person of Hispanic descent to receive the award.

He additionally received two French Croix de Guerre with palms for his actions.

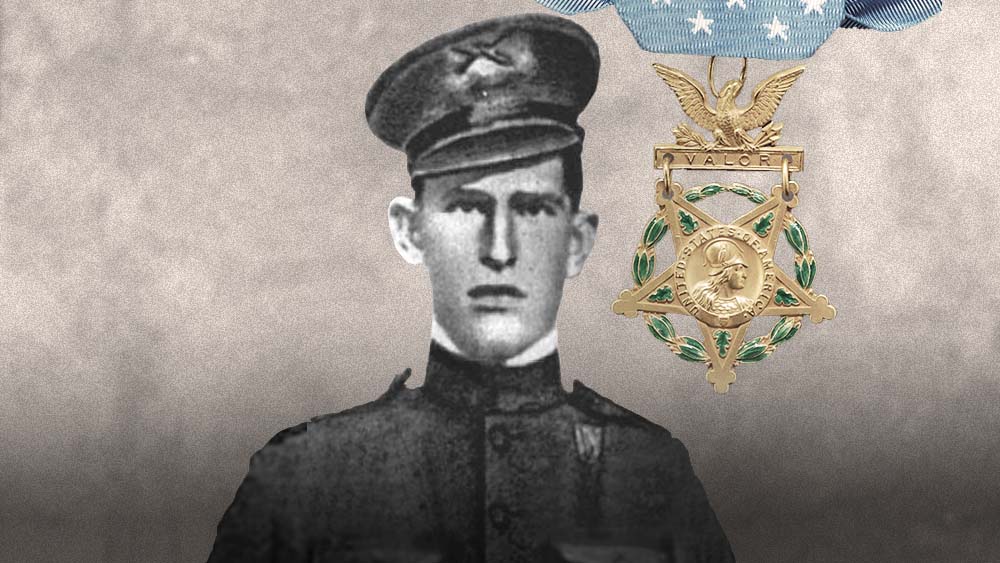

Pvt. David Barkley, the only Hispanic American to receive the Medal of Honor in WWI. Courtesy photo.

Pvt. David Barkley awarded Medal of Honor

Pvt. David Barkley was born in Laredo, Texas to Joseph Barkeley and Antonia Cantu. At 17, Barkley enlisted in the Texas National Guard in April 1917, shortly after the United Stated entered World War I. It is believed that Barkley decided to enlist under the anglicized version of his name in order to avoid being placed within a segregated unit.

In August 1918, Barkley arrived in France and was assigned to Company A, 356th Infantry, 89th Division.

On Nov. 9, 1918, Barkley, along with Pvt. Waldo Hatler, volunteered for a reconnaissance mission. This mission entailed swimming across the Meuse River near Pouilly, France, to obtain information on the enemy’s position, deployment and strength while scouting behind enemy lines, hopefully returning with drawn maps of the enemy encampment.

On the way back, Barkley’s legs cramped and he drowned. The mission succeeded, though, as Hatler made it back.

After his body was retrieved, Barkley was honored by being laid to rest in state at the Alamo. He was the second soldier to have received such an honor, and he was later interred at the San Antonio National Cemetery.

Because of his heroic sacrifice, Barkley was posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor — the only Hispanic American to receive the medal in World War I. Barkley also received a Purple Heart, a French Croix de Guerre and an Italian Croce al Merito di Guerra for his actions.

WORLD WAR II

Overview

About 500,000 Hispanics served in the U.S. military during World War II. Although they were integrated throughout the armed forces, many National Guard and Reserve units mobilized from southern and southwestern states contained high percentages of Hispanic Americans. The Arizona National Guard's 158th Infantry won fame as the "Bushmasters" of the southwest Pacific. The regiment spent 312 days in combat in New Guinea and the Philippines and was hailed by General Douglas MacArthur as "one of the greatest fighting combat teams ever deployed for battle." Another unit from the American southwest, the 141st Infantry of the Texas National Guard, also distinguished itself in the European Theater. Fighting in Italy and France for almost a full year with the 36th Division, the regiment suffered almost 7,000 battle casualties many as part of the ill-fated Rapido River crossing in Italy. Soldiers of the 141st received 3 Medals of Honor, 31 Distinguished Service Crosses, almost 500 Silver Stars, and some 1,700 Bronze Stars.

Out of 440 Medals of Honor awarded to American servicemen during World War II, twelve were received by Hispanics. In fighting near Metzwillers, France on March 15, 1945, Pfc. Silvestre S. Herrera, 142nd Infantry, 36th Infantry Division, advanced alone against an enemy strongpoint, capturing eight German soldiers. He continued his advance toward a second strongpoint until he was severely wounded in an enemy minefield. Despite his wounds, he continued to fire upon the enemy position until it was overrun by another squad. Pfc. David M. Gonzalez of the 127th Infantry, 32d Infantry Division, received his Medal of Honor for actions along the Villa Verde Trail on the island of Luzon in the Philippines. On April 25, 1945, with his company pinned down by enemy fire, Gonzalez rushed forward to assist five fellow soldiers who had been buried in the explosion of a 500-pound bomb. Using bare hands and an entrenching tool, he was able to rescue three of the men before he was hit by enemy sniper fire and fell mortally wounded.

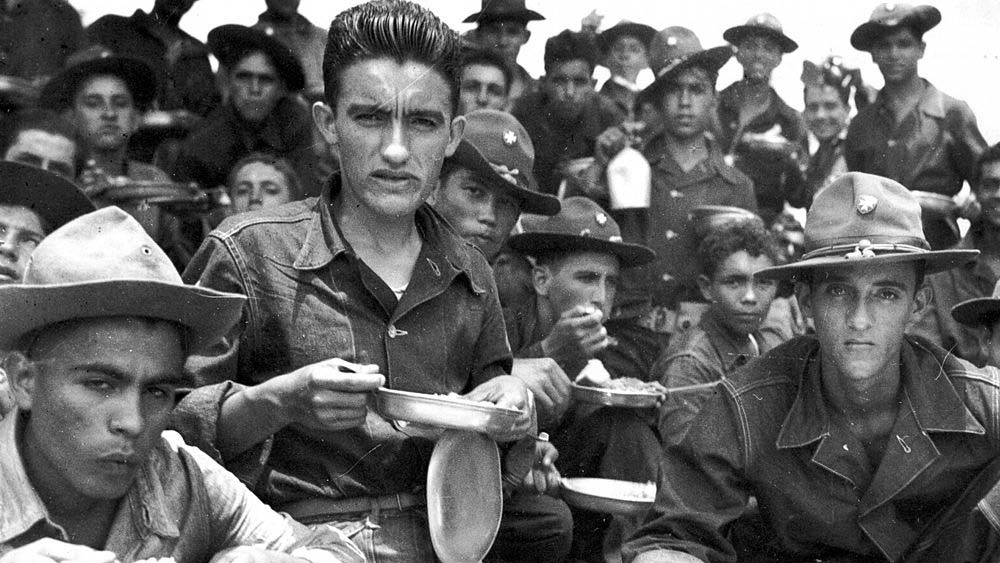

Group photo of Charlie Company 158th Infantry Regiment “Bushmasters” named after the venomous pit vipers found in Central America. Guadalupe “Lupe” Lopez (second row from the back, sixth person from the right) was awarded a Silver Star for fearless actions on Jan. 14, 1945, which became known to the Bushmasters as “Bloody Sunday” and was the largest number of casualties sustained by the 158th in any battle during the regiment's history. Photo Courtesy of the Lopez Family.

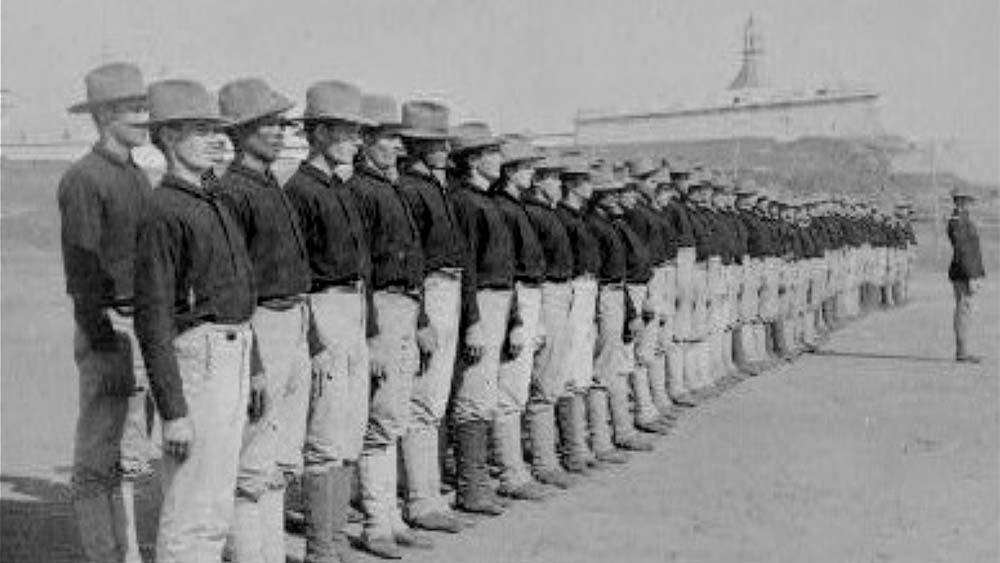

Soldiers of the 65th Infantry Regiment training in Salinas, Puerto Rico; August, 1941. U.S. Army photo.

The 65th Infantry Regiment

Although Puerto Rico lies almost 5,000 miles east of Pearl Harbor, the events of December 7, 1941 had a profound effect on the island’s people and way of life. Puerto Rico mobilized its population and economy for the war effort, rationing and sacrificing alongside Americans throughout the country.

Thirteen months after Pearl Harbor and the U.S. entrance into World War II, the 65th Infantry deployed in January 1943 to the Panama Canal Zone, where their predecessors served 26 years earlier — continuing a legacy of service from World War I.

On February 4, 1944, the 65th Infantry was ordered to North Africa in preparation for the invasion of Europe. While there, the Puerto Rican Soldiers conducted amphibious training and security operations. In North Africa, Col. Antulio Segarra, a native of Cayey, Puerto Rico, took command of the 65th Infantry. In doing so, Segarra made history as the first Puerto Rican officer to command a regiment in the regular U.S. Army.

Finally, in October 1944, the 65th Infantry was assigned to the Seventh Army to help defeat German forces in southern France and end the war.

Members of the 158th Infantry Regiment conduct jungle warfare battle drills in Panama in 1942. Frequent dealings with the deadly snakes of the jungle, lead to the unit adopting the name “Bushmasters” after the venomous pit vipers found in Central America. Photo Courtesy of the Arizona State University Libraries Collection.

The Bushmasters — From Arizona to Japan in 5 years

In the World War II Army, the 158th Infantry, Arizona National Guard, was unique. Descended from the 1st Arizona Volunteer Infantry of the Civil War era, the regiment consisted of Mexican American Soldiers and representatives from twenty Native American tribes.

It formed part of the 45th Infantry Division when that unit went on active duty in 1940, but after Pearl Harbor, it went to the Panama Canal Zone as a separate regiment. There, it conducted security patrols and helped with jungle warfare training. It also adopted the nickname Bushmasters after the venomous snake that inhabited the region.

In January 1943, the regiment deployed to Australia. After a period of security duty, it entered combat for the first time at the end of the year near Arawe, New Britain, as part of MacArthur’s New Guinea campaign. Through the spring of 1944, the Bushmasters participated in hard fighting in New Guinea, killing an estimated 920 Japanese soldiers but losing 330 of their own.

Joining MacArthur’s return to Luzon, Philippines, in January 1945, the Bushmasters took heavy casualties in attacks against dug-in Japanese troops along the Damortis-Rosario Road. In “Two-Gun Valley,” Company G earned the Presidential Unit Citation for capturing 2 Japanese howitzers and killing 164 enemy troops. In April, the regiment advanced through Luzon’s Bicol Peninsula as part of the overall objective of clearing the Visayan Sea passage through the central islands of the Philippines.

It completed its Pacific odyssey by landing in Yokohama in October 1945 to participate in the occupation of Japan. General MacArthur would later say of the Bushmasters, “No greater fighting combat team has ever deployed for battle.”

Carmen Lozano Dumler was one of the first Puerto Rican women to become a United States Army officer. Photo courtesy of the National Archives.

Hispanic American women join the ranks

Many Hispanic American women have also put their lives on the line to serve this country and protect what it stands for.

Carmen Lozano Dumler, RN, one of the first Puerto Rican women to become a U.S. Army officer, shows the dedication of Hispanic American women to serve our country.

In 1944, because of War World II, the U.S. Army sent some members of the Women’s Army Corps to Puerto Rico to recruit more people. That’s where Dumler heard about this opportunity to help out. Upon graduating from Presbyterian Hospital School of Nursing in the spring of 1944, Dumler volunteered as an Army nurse. As one of 13 selected applicants, she became a second lieutenant. She described it as the happiest day of her life.

Dumler served in different hospitals, providing her knowledge as a translator and her support to the patients who appreciated having someone to talk to who shared the same language. She trained as a nurse at the Rodriguez General Hospital in San Juan, Puerto Rico. Dumler later served in the British West Indies, where she attended to wounded Soldiers returning from France.

Members of the 1st Battalion, 141st Infantry Regiment, 36th Infantry Division. A battalion cut off by the Germans for six days in the Belmont sector, France. October 30, 1944. Photo courtesy the of the National Archives.

The 141st Infantry Regiment — The "Lost Battalion" stand their ground

Another unit from the American southwest, the 141st Infantry of the Texas National Guard, also distinguished itself in the European Theater.

Fighting in Italy and France for almost a full year with the 36th Division, the regiment suffered almost 7,000 battle casualties. Many of the units losses came as part of the ill-fated Rapido River crossing in Italy in January, 144.

Additional casualities were experienced after being cut off by the Germans in the Vosges Mountains in October, 1944, becoming the “lost battalion” in Europe in World War II. The battalion was later rescued by the 442nd Regimental Combat Team — an all-Japanese American unit known by their motto: “Go for Broke!”

Soldiers of the 141st Infantry Battalion went on to receive 3 Medals of Honor, 31 Distinguished Service Crosses, almost 500 Silver Stars and some 1,700 Bronze Stars.

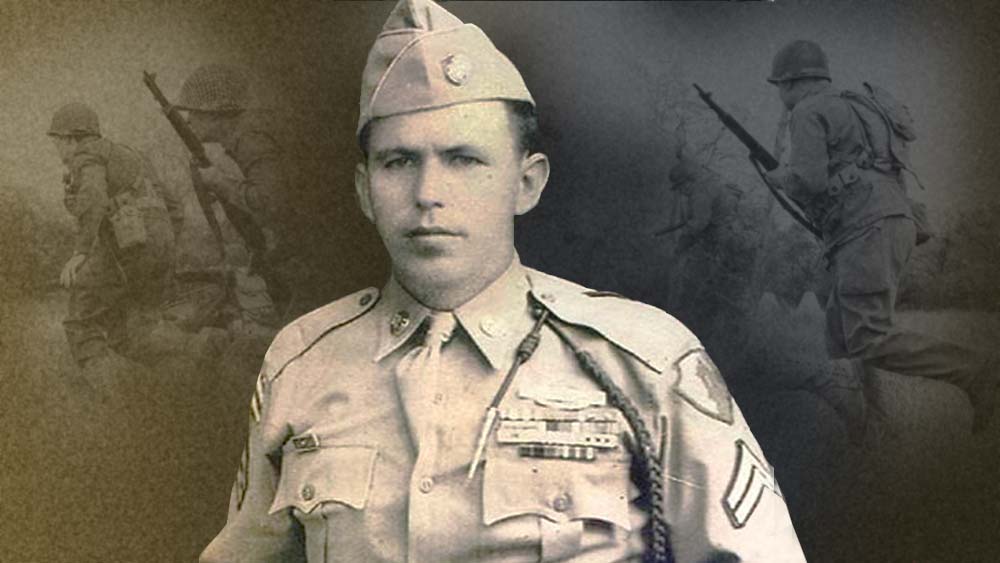

Sgt. 1st Class Agustín Ramos Calero, known as the “One-man Army,” was the most decorated Hispanic American Soldier of World War II.

Sgt. 1st Class Agustín Ramos Calero — "One-man Army"

Sgt. 1st Class Agustin Ramos Calero enlisted in the Army in 1941 as an Infantryman. He was assigned to Puerto Rico’s 65th Infantry Regiment at Camp Las Casas in Santurce, Puerto Rico.

Upon the outbreak of World War II, Calero was reassigned to the 3rd Infantry Division and was sent to Europe with the 65th Infantry Regiment.

In 1945, Ramos’ company was in the vicinity of Colmar, France, and engaged in combat against a squad of German soldiers in what is known as the Battle of Colmar Pocket. Calero attacked the squad, killing ten of them and capturing 21 shortly before being wounded himself.

Following these events, he was nicknamed “One-man Army” by his comrades. For his actions he was awarded 22 decorations, including the Silver Star.

During the Korean War, he returned to fight with the 65th Infantry Regiment in Busan, Korea. In Korea, the Soldiers played a vital role pushing North.

Calero later retired from the Army in 1962.

Donald Lopez sits inside the cockpit of his P-51C Mustang "Lope's Hope III," in Chiahkiang, China, Nov. 11, 1944. Photo courtesy of the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum.

Flying Aces

In order to become an “ace,” a fighter pilot must be credited with shooting down at least five enemy aircraft during aerial combat.

During World War II, several Hispanic Americans became “aces.”

Capt. Michael Brezas of the 48th Fighter Squadron is credited with 12 kills in two months during the war in Europe. He received the Silver Star, Distinguished Flying Cross and the Air Medal with eleven oak leaf clusters.

1st Lt. Oscar Perdomo of the 464th Fighter Squadron became an “ace in a day” after downing six Japanese aircraft on Aug. 13, 1945. He received the Air Medal with one oak leaf cluster and the Distinguished Service Cross.

Lt. Col. Donald Lopez flew more than 100 combat missions while based in China with the 23rd Fighter Group. He is credited with shooting down five Japanese planes. He received the Distinguished Flying Cross and the Silver Star. Lopez also went on to aid in planning the construction and opening of the National Air and Space Museum, part of the Smithsonian Institution, and later served as the deputy director of the museum.

KOREAN WAR

Overview

Altogether, 148,000 Hispanics served in the U.S. military during the Korean War — including 61,000 Puerto Ricans. During that war, many earned awards for valor, from Bronze Star Medals to Medals of Honor. Among the notable recipients is Gen. Richard E. Cavazos, who served with the 65th Infantry Regiment in Korea and later in Vietnam. The largest single contingent deployed with Puerto Rico's 65th Infantry, which, with a total strength of over 4,000 troops, was the largest U.S. infantry regiment in the war.

Other Hispanics served in integrated units throughout Korea, many with distinction. Pfc. Joseph C. Rodriguez served as a rifleman and assistant squad leader with the 17th Infantry, 7th Infantry Division. On 21 May 1951, near Munye-ri, South Korea, he singlehandedly destroyed five enemy emplacements and forced the remaining defenders to flee. For his actions, Rodriquez received the Medal of Honor. Another Medal of Honor recipient during the Korean War was Cpl. Benito Martinez of the 27th Infantry, 25th Infantry Division. On December 29, 1953, while manning a listening post forward of the main defensive line, Martinez was attacked by a company-size enemy force. Ordering three other Soldiers manning the position to the rear, the corporal elected to remain at his post and inflicted numerous casualties using a machine gun and automatic rifle. After resisting enemy attacks for six hours, Martinez reported that the enemy was closing in on his position. Although he was overrun and mortally wounded, his determined resistance allowed his unit to hold its position and repel the enemy assault.

Painting depicting Soldiers of the 65th Infantry Regiment with bayonets fixed to their rifles charging enemy positions held by the Chinese 149th Division just south of Seoul during Operation Thunderbolt, Feb. 2, 1951. Painting by Dominic D'Andrea, commissioned by the National Guard Heritage Foundation and courtesy of the National Guard Bureau.

Fighting from 1950 to 1952, the men of the 65th Infantry Regiment won four Distinguished Service Crosses and 125 Silver Stars, among numerous other awards. Courtesy photo.

The Borinqueneers — The 65th Infantry Regiment serves in Korea

By the Korean War era, the all-Hispanic 65th Infantry Regiment had adopted the nickname “The Borinqueneers” — a soubriquet that stems from Borinquen, the Taino name for the island of Puerto Rico. Many members of the 65th were direct descendants of Taino descent.

Although senior commanders and some staff officers were “continentals” from the regular Army, the regiment was overwhelmingly Hispanic. The regiment deployed to Korea in September 1950, taking part in the breakout from the Pusan Perimeter and the drive northward.

The 65th Infantry Regiment, along with the rest of the 3rd Infantry Division, helped to hold open mountain passes as the 1st Marine Division withdrew from Chosin, and then formed part of the defensive perimeter around Hungnam harbor as United Nations forces evacuated the city.

During service in Korea, Soldier with the regiment received four Distinguished Service Crosses and 125 Silver Stars. The 65th also received Presidential Unit Citation, the Army Meritorious Unit Commendation, two Korean Presidential Unit Citations and the Greek Gold Medal for Bravery.

The regiment was finally integrated in March 1953 and remained in Korea until November the following year. By the end of the Korean War, Puerto Ricans served throughout the Army.

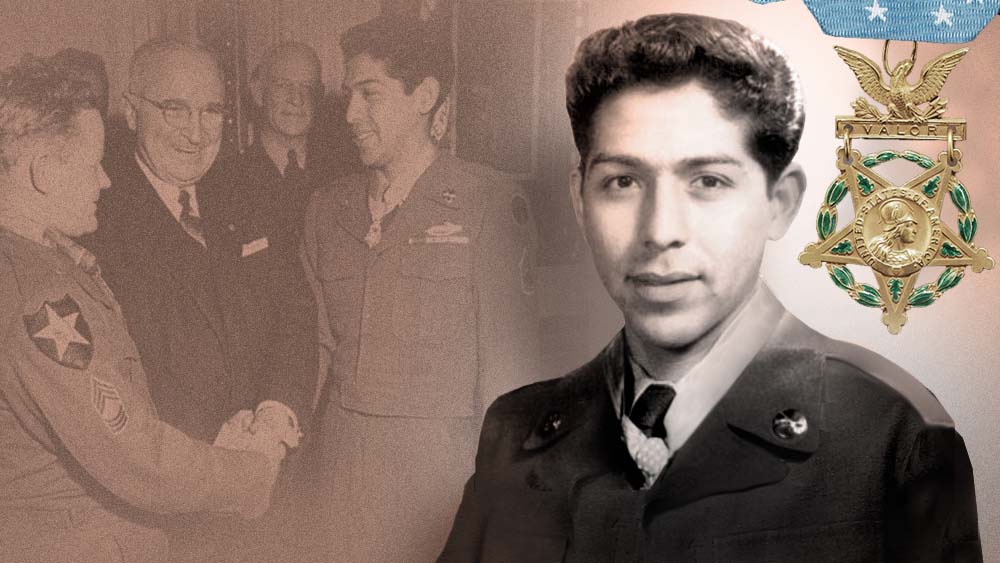

Then-Pfc. Joseph Charles Rodriguez earned the Medal of Honor for his actions near Munye-ri, Korea, during the Korean War. On February 5, 1952, President Harry S. Truman bestowed upon Sergeant Rodríguez the Medal of Honor in a ceremony held in the Rose Garden in the White House. Courtesy photo.

Then-Pfc. Joseph Charles Rodríguez earns the Medal of Honor

On May 21, 1951, then-Pfc. Rodriguez led a squad from F Company, 17th Infantry Regiment of the 7th Infantry Division, on a mission to take a strategic hill near the small village of Munye-Ri, Korea. That mission resulted in Rodriguez being awarded the nation’s highest honor.

The effort was part of a massive counter attack by the U.S. to regain ground in the Korean War. But the hill was firmly entrenched with Chinese forces. F Company had attempted to take the hill three times only to be repelled. Then a squad from 2nd Platoon, which included Rodriguez, got the call to attempt another assault up the high ground.

The group immediately came under heavy fire and the squad was unable to press forward or withdraw. With progress halted and frustration building, Rodriguez seethed. He couldn’t see where the enemy fire was coming from, only aware it was coming from high up on the hill.

“I felt something had to be done,” Rodriguez said. “I didn’t even think about it. I just did it.”

Rodriguez sprang from his pinned position and sprinted toward the top of the hill. The jaunt was 60 yards into the teeth of five machinegun nests, which Rodriguez silence with grenades.

Rodriguez’s actions, according to his Medal of Honor citation, “exacted a toll of 15 enemy dead and, as a result of his incredible display of valor, the defense of the opposition was broken, and the enemy routed, and the strategic strongpoint secured. His unflinching courage under fire and inspirational devotion to duty reflect highest credit on himself and uphold the honored traditions of the military service.”

He was subsequently promoted to sergeant and was decorated with the Medal of Honor on Feb. 5, 1952, by President Harry S. Truman during a ceremony in the Rose Garden at the White House.

Rodriguez made a career of the Army, becoming a commissioned officer in 1953 with the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. He served more than 30 years, including four assignments in Latin America. He retired as a colonel in 1980.

Cpl. Rodolfo "Rudy" Hernández was awarded the Medal of Honor for his selfless actions in May 1951. U.S. Army photo.

Cpl. Rudy Hernández — Valiant on Hill 420

Cpl. Rodolfo “Rudy” Hernandez and Company G, 2nd Battalion, 187th Airborne Regimental Combat Team were dug in at Hill 420, about 15 miles south of the current Demilitarized Zone near Wontong-ri, South Korea, May 31, 1951.

They heard the North Korean bugles that heralded a charge at about 2 a.m. A much larger force attacked their position with heavy artillery, mortar and machine gun fire. They quickly ran low on ammunition and began to withdraw. Not Hernandez. Although he had been wounded by a grenade, he wanted to buy his comrades time. He fixed his bayonet and rushed the enemy. He killed six enemy fighters before losing consciousness from his injuries.

His actions momentarily halted the enemy advance, giving his unit a chance to retake the lost ground. A medic found Hernandez at daybreak, wounded so severely that he was declared dead at the aid station. Medics were preparing to zip him in a body bag when one of them saw his finger move.

After months of rehab, Hernandez was able to stand for his Medal of Honor ceremony in April 1952. He eventually joined the Department of Veterans Affairs, working with other wounded veterans in North Carolina.

VIETNAM WAR

Overview

By the 1960s and the Vietnam War, the U.S. Army was fully integrated and Hispanic Americans served throughout the force. There were no all-Hispanic units and the military did not record separate data on Hispanic participation. Approximately 80,000 Hispanic Americans served in the U.S. armed forces during the war. A U.S. Senate resolution from the 115th Congress recognizing the 2017 Hispanic Heritage Month stated Hispanic Americans suffered 5.5% of Vietnam War deaths and made up 4.5% of the general U.S. population.

As in previous wars, Hispanic American troops performed admirably. One was sgt. 1st Class Isaac Camacho, a member of a U.S. Special Forces team supporting a Civilian Irregular Defense Group camp at Hiep Hoa. When the camp was attacked and overrun by a reinforced Viet Cong battalion in November 1963, Sgt. 1st Class Camacho returned fire from his mortar position until he was captured by enemy troops. Held captive for almost twenty months, Camacho managed to escape in July 1965, and made his way back to friendly positions. For his role in the defense at Hiep Hoa and for his successful escape, he was awarded the Bronze Star and the Silver Star. Promoted to master sergeant, he later received a battlefield commission to captain.

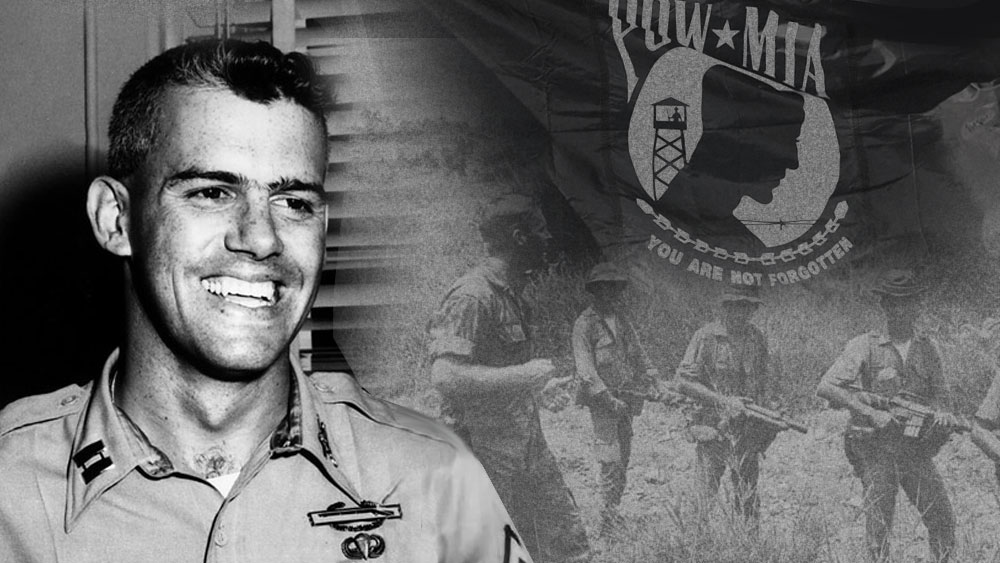

Isaac Camacho, was awarded the Bronze Star and Silver Star for his role in the defense of Hiep Hoa, after his successful escape from a POW camp. Courtesy photo.

Capt. Humbert Roque "Rocky" Versace, a selfless, brave and devoted Soldier was awarded the Medal of Honor for his actions during the Vietnam War. U.S. Army photo.

Capt. Humbert Roque "Rocky" Versace

Born to an Army colonel father and a Puerto Rican author mother, Capt. Humbert “Rocky” Versace received his commission at the U.S. Military Academy at West Point, New York, in 1959. After graduating from Ranger and Airborne schools, he served in Korea with the 1st Cavalry Division. He then volunteered to go to Vietnam as an advisor.

In October 1963, Versace’s South Vietnamese unit came under intense mortar, automatic weapons and small arms fire during a mission to destroy a Viet Cong command post. Although he was severely wounded in the knee and back, Versace continued to fight and resist capture as long as he had ammunition.

After he was finally taken prisoner, Versace, who could speak French and Vietnamese, withstood exhaustive interrogations, torture and abuse for 23 months without breaking. He attempted to escape four times and inspired other prisoners of war. In fact, the last time they heard his voice, he was singing “God Bless America.”

Versace was finally isolated from other POWs in a series of jungle camps, caged, manacled and placed on extremely reduced rations. The North Vietnamese announced his execution, Sept. 26, 1965. His body has never been recovered. Versace was nominated for the Medal of Honor in 1969 when an escaped POW documented his bravery, but the award was downgraded to a Silver Star. He was finally awarded the medal in 2002.

THE COLD WAR ERA

Overview

After the 1959 Cuban revolution, hundreds of thousands of Cubans fled their homeland, some of which took the chance to fight communism as part of the U.S. Armed Forces. In addition to the Cuban migration during the 1960s, the post-Vietnam War era coincided with increased immigration from Latin America and the Caribbean for myriad socioeconomic reasons. The phenomenon renewed and magnified the connection between military service and the quest for inclusion.

In March 1976, in response to rising concerns over disproportionate numbers of Black Americans in combat arms units, the Department of the Army formed a Standing Committee on Equal Opportunity, to review policies regarding the treatment of and opportunities for minorities. In 1978, the resulting plan for the Army required the collection of more detailed data on ethnic minorities and recommended that the service employ U.S. Department of Commerce standard classifications of white, Black, Hispanic, Asian and Native Americans.

Soldiers would now be identified as Hispanic Americans and provided equal promotion protections and opportunities. Over time, Hispanic Americans earned promotions to the top ranks of the U.S. Army. In 1982, Gen. Richard E. Cavazos, a Mexican American, became the service's first Hispanic American four-star general.

Col. Maritza Sáenz Ryan broke barriers as a member of one of the first co-ed classes at the United States Military Academy, where she later went on to become the first woman and first Hispanic American department head. U.S. Army photo.

Col. Maritza Sáenz Ryan — Among the first Hispanic American women to graduate from West Point

In 1975, President Gerald R. Ford signed legislation allowing women to attend all service academies beginning the following year. On July 7, 1976, the first 119 women arrived at West Point for “Reception Day” and the start of their Cadet Basic Training.

Despite the obstacles that they faced upon their arrival, the majority of the women soon thrived at West Point. At the beginning of their second academic year, 69% of the first women who arrived remained at the academy, a rate only 10% lower than their male peers, and a remarkable feat given the challenges they faced. Women soon made strides in the realm of academics and athletics. In the second year at West Point, the top academic student in the class of 1980 was a woman. The nascent women’s basketball and volleyball teams won their respective state titles in their first year, earning a varsity status and their peer’s respect. When graduation arrived on May 27, 1980, 61 of the original 119 women walked across the stage on The Plain of West Point to receive their diplomas and Army commissions.

One example was Maritza Sáenz Ryan who in the late 1970s was accepted to West Point. Sáenz Ryan was a member of only the third class to include women cadets at West Point. She graduated from West Point in 1982 and was commissioned as a second lieutenant in the field artillery. In 2006 she went on to become head of West Point's Department of Law — which requires a presidential nomination and confirmation by Congress. This made her the first woman and first Hispanic American to serve as a West Point department head.

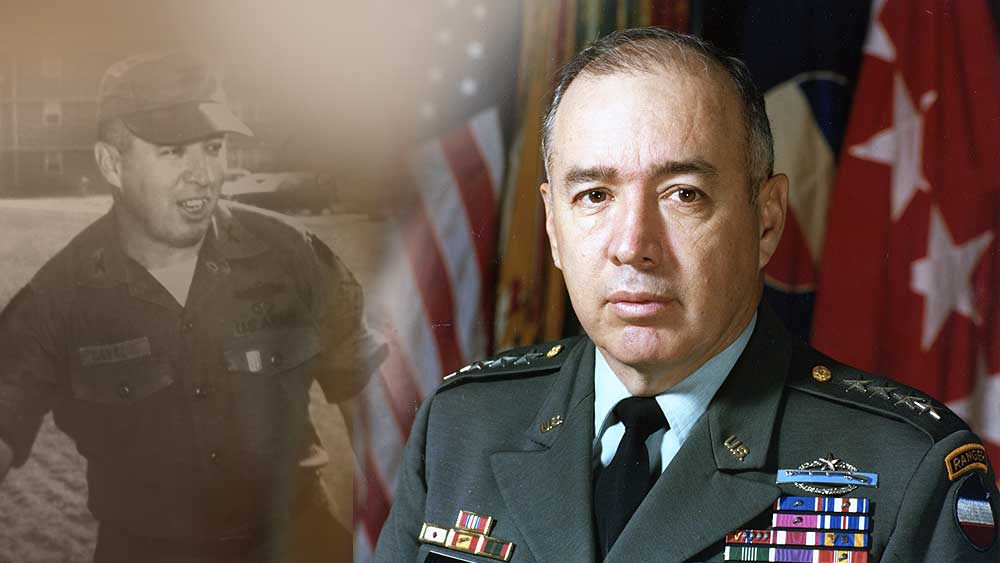

From growing up on a cattle ranch, sustaining a career-ending football injury in college, and facing enemy forces in both the Korean and Vietnam Wars, Gen. Richard E. Cavazos learned from his life experiences and used them to become one of the Army’s finest Soldiers. He served as the first four-star general of Hispanic descent in Army history. U.S. Army photo.

Gen. Richard E. Cavazos — First Hispanic American four-star general

Gen. Richard Edward Cavazos was the first Hispanic American four-star general in the United States Army. Raised in Kingsville, Texas, he graduated from Texas Technological College, now Texas Tech University, in 1951 with a degree in geology, but he chose to follow in his father's footsteps and join the Army. After his college graduation, Cavazos received his commission. During the Korean War, he led the renowned 65th Infantry Regiment, also known as the Borinqueneers, the Army's only all-Hispanic unit attached to the 3rd Infantry Division.

Throughout his 33 years of distinguished service in the military, including serving in the Korean and Vietnam Wars, Cavazos demonstrated exceptional leadership and bravery. Because of this, he earned multiple service medals, including two Distinguished Service Crosses, a Silver Star, five Bronze Stars and a Purple heart. The Distinguished Service Cross is the second-highest military award that can be given to a member of the Army for extraordinary heroism in combat. In 2023 Fort Hood, the third-largest U.S. military base, was redesignated Fort Cavazos in honor of his distinguished service.

GULF WAR

Overview

In 1990 and 1991, 20,000 Hispanic Americans took part in Operations Desert Shield and Desert Storm. At that time, they comprised 4.2 percent of the Army. By December 2008, 45.4 million Hispanic Americans constituted about 15.1 percent of the U.S. population. Of those, 53,571 served in the enlisted ranks of the Army, making up almost 12 percent of the enlisted force. Another 5,429 served as officers, about 6 percent of the total officer strength. Altogether, some 59,000 Hispanics made up about 10.8 percent of the active Army's personnel strength of 542,565.

On 2 July 1998, Louis E. Caldera, a Mexican American and West Point graduate, became the highest-ranking Hispanic American to hold office when he became Secretary of the Army. During his tenure the Army began a transition from its Cold War orientation to a rapidly deployable expeditionary force. Secretary Caldera's encouragement of programs to upgrade enlisted Soldiers' skills and education opportunities helped to prepare the Army for the Information Age.

U.S. Army Soldiers assigned to the 82nd Airborne Division's 1st Battalion, 505th Parachute Infantry Regiment, take a water break while conducting machine gun drills during Operation Desert Shield. U.S. Army photo.

Operation Desert Shield & Operation Desert Storm

Operation Desert Shield and Operation Desert Storm provided another opportunity for Hispanics to serve their country. This war brought together a coalition military force composed of NATO member countries to oppose Iraq’s invasion of our ally Kuwait on Aug. 2, 1990.

Approximately 20,000 Hispanic American servicemen and women participated in Operations Desert Shield and Desert Storm. According to Defense Manpower Data Center statistics, they comprised 4.2 percent of the Army representation in the Persian Gulf theater.

Lt. Gen. Edward Baca poses for his official portrait. U.S. Army photo.

Lt. Gen. Edward Baca — First Hispanic American to serve as chief of the National Guard Bureau

Lt. Gen. Edward Baca enlisted in the U.S. Army in November of 1956, with the 726th Anti-Aircraft Artillery Battalion of the New Mexico Army National Guard. Upon graduation from Officer Candidate School in July 1962, he was assigned as a platoon leader of the 3631st Maintenance Company. Soon after, he volunteered for Active Duty and for overseas deployment to Vietnam. Baca was released from Active Duty in 1966 and returned to the New Mexico Army National Guard, where he assumed command of the 3631st Maintenance Company. In 1977, Baca became the state military personnel officer and was assigned the state assistant, G-1. A short time later, he was appointed the adjutant general, New Mexico National Guard. Commanding both the Army and Air National Guard of New Mexico, Baca led the state guard to a position of national prominence as a vital component of the “total force.”

Baca spearheaded a nationwide National Guard force modernization effort and directed the first fielding of the Chaparral and Hawk missile battalions in the U.S. Army Reserve. In October of 1994, Baca was promoted to lieutenant general and assigned as chief, National Guard Bureau, a position he held until his retirement in 1998.

Louis Caldera poses for his official portrait. U.S. Army photo.

Louis Caldera — First Hispanic American Secretary of the Army

Louis Caldera was the 17th United States Secretary of the Army, from July 1998-January 2001. Caldera is of Mexican descent, born on April 1, 1956, in El Paso, Texas.

He earned a Bachelor of Science degree in 1978 from the United States Military Academy at West Point, New York, then served on active duty in the U.S. Army from 1978 to 1983, retiring as a captain. He went on to enroll at Harvard University and in 1987 earned a joint Juris Doctor and Master of Business Administration degree from Harvard Law School and Harvard Business School, respectively.

THE WAR ON TERROR AND BEYOND

Overview

The international military campaign from the Sept. 11, 2001 attacks started the Global War on Terrorism, Operation Iraqi Freedom and Operation Enduring Freedom. As a result of this, thousands of Hispanic American U.S. Army Soldiers placed their boots on the ground in more than 120 countries around the world. In 2013, President Barack Obama announced that the United States would no longer pursue a “War on Terror,” as the military focus should be on specific enemies rather than a tactic.

Hispanic American Soldiers continue to engage in contingency operations throughout the world — fighting the enemy on distant shores, as well as protecting the homeland in the most noble of endeavors. Today, just as in generations past, Hispanic American Soldiers — both men and women — can be especially proud of their significant contributions to the war effort and embodying the U.S. Army's values that unite all service members as one.

The Hispanic community continues its selfless sacrifice in bringing freedom to people in other countries, making major sacrifices and risking their lives to bring justice to terrorists and lay a foundation for a sustainable peace. Hispanics have a proud and indeed enviable record of military service, dating all the way back to the Civil War. Whether their heritage can be traced to Spain, Cuba, Puerto Rico, Mexico, or one of dozens of other Spanish-speaking countries or cultures, they've answered the call to duty, defending America with unwavering valor and honor.

Profiles of Hispanic Americans in the U.S. Army Today. Left to right: [1.] U.S. Army Spc. Marcos Nunez, a field artillery firefinder radar operator assigned to 3rd Infantry Division Artillery; [2.] U.S. Army Chief Warrant Officer 2 Mathew D. Macias, a rotary wing aviator assigned to 3rd Combat Aviation Brigade, 3rd Infantry Division; [3.] U.S. Army Lt. Col. Alexis “Pancho” Perez-Cruz, the 3rd Infantry Division operations officer; [4.] U.S. Army Sgt. Stacy Ortiz Kuilan, an aviation operations noncommissioned officer assigned to Headquarters and Headquarters Company, 3rd Combat Aviation Brigade, 3rd Infantry Division; [5.] U.S. Army Pfc. Israel Vital, an indirect fire infantryman assigned to 6th Squadron, 8th Calvary Regiment, 2nd Armored Brigade Combat Team, 3rd Infantry Division.

Leroy Arthur Petry is a retired United States Army Soldier. He received the U.S. military's highest decoration, the Medal of Honor, for his actions in Afghanistan in 2008 during Operation Enduring Freedom. DOD photo.

Then-Sgt. Leroy Arthur Petry awarded Medal of Honor

While assigned to Company D, 2nd Battalion, 75th Ranger Regiment, then-Staff Sgt. Leroy Petry participated in a rare, daring daylight raid to capture a high-value target in Paktya Province, Afghanistan, May 26, 2008. He was clearing a courtyard with another Ranger when an enemy combatant opened fire, wounding Petry in the legs and hitting his comrade in his side plate.

Petry helped his Soldier take cover and threw a grenade toward the enemy to cover the arrival of a third Soldier. An enemy grenade injured both of the other Soldiers, and then a second landed a few feet from them. As Petry grabbed the grenade to throw it away from his fellow Rangers, it detonated and amputated Petry’s right hand. Petry then assessed his own wound and placed a tourniquet on his right arm.

At that point other Rangers were able to target and destroy the enemy. Petry became the second living Medal of Honor recipient from the War in Afghanistan in July 2011. He retired from the Army as a master sergeant in 2014.

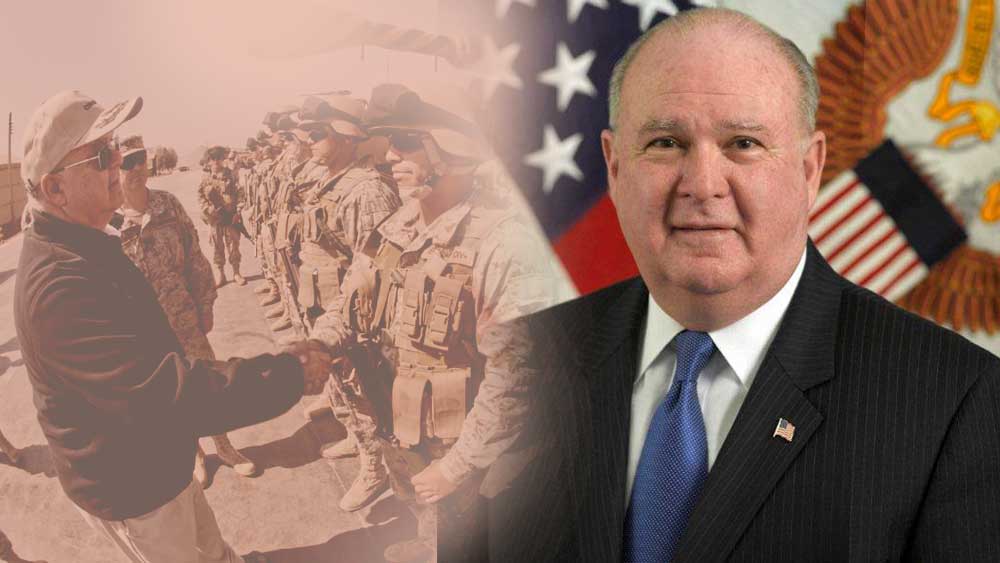

As the 30th Undersecretary of the Army Dr. Joseph W. Westphal advocated and improved diversity and opportunity across the Army; developed and expanded relations with Congress, business and academia and had been a tireless advocate for supporting wounded warriors. U.S. Army photo.

Dr. Joseph W. Westphal — First Hispanic American Undersecretary of the Army

Dr. Joseph W. Westphal served as the 30th under secretary of the Army, and in that position he was responsible for providing trained and ready forces for combat commanders. As the 30th under secretary of the Army, from September 2009 to March 2014, Westphal’s tenure in the position was the second longest in U.S. Army history.

The 21st Secretary of the Army John McHugh stated that during Westphal’s tenure, the former under secretary contributed to increasing education and professional development for Soldiers, Civilians and Family members; engineered the Army’s business transformation as its first chief management officer; advocated and improved diversity and opportunity across the Army; developed and expanded relations with Congress, business and academia; and had been “a tireless advocate” for supporting wounded warriors.

Westphal was born in Santiago, Chile, received his bachelor’s degree from Adelphi University, his master’s degree from Oklahoma State University and his doctorate in political science from the University of Missouri-Columbia.

Left to right: Sgt. 1st Class Melvin Morris, Master Sgt. Jose Rodela and Sgt. Santiago J. Erevia. All three earned the nation’s highest award for battlefield gallantry during the Vietnam War. They are among 24 Soldiers from World War II, the Korean War and the Vietnam War that originally received the Distinguished Service Cross, but had their awards upgraded after a congressionally directed review. DOD photo by E.J. Hersom.

Valor 24 - One of the largest Medal of Honor ceremonies in history

Congressional review and the 2002 National Defense Authorization Act prompted a review of Jewish American and Hispanic American veteran war records from World War II, the Korean War and Vietnam War. As a result, 24 Soldiers received long-overdue Medals of Honor — 17 of the recipients were Hispanic Americans.

Brig. Gen. Irene M. Zoppi Rodríguez became the first Puerto Rican woman promoted to the rank of brigadier general in the U.S. Army Reserve in 2017. U.S. Army photo.

Brig. Gen. Irene M. Zoppi Rodríguez — first Hispanic American woman promoted to general in the U.S. Army Reserve

Brig. Gen. Zoppi became the first Puerto Rican woman promoted to the rank of general in the U.S. Army Reserve on Aug. 28, 2017. After promoting, she served as the deputy commanding general for the 200th Military Police Command, the largest military police organization in the Department of Defense, and on the civilian side was a program director for the National Intelligence University — which is run by the National Security Agency.

Notable Military Unit Histories

158th Infantry Regiment — The Bushmasters

During World War II this Arizona National Guard unit was one of the first to see combat in the Pacific; they were nicknamed the “Bushmasters” and described by General MacArthur as “one of the greatest fighting combat teams ever deployed.

200th Coast Artillery

200th Coast Artillery was a New Mexico National Guard unit sent to bolster Philippine defenses during WWII; when Japan attacked the Philippines six hours after Pearl Harbor the 200th became among the “first to fire” in the Pacific theater; later captured, the 200th was forced on the 85-mile “Bataan Death March” to a Japanese prison camp where they remained for three and half years; only half of the unit survived.

65th Infantry Regiment — The Borinqueneers

The only all-Hispanic unit to serve during the Korean War; nicknamed the “Borinqueneers” in honor of a native Puerto Rican Indian tribe; earned numerous awards and citations.

141st Infantry Regiment

Elements of the 141st Infantry Regiment have fought in the Spanish-American War, Cuban Occupation, Civil War, World War I, World War II, and The War on Terrorism. During the WWI the regiment distinguished itself with participation in one of the greatest chapters in its combat history, the Meuse-Argonne campaign. Notable achievements of the 141st during the WWII include claim to the first to land in Europe, first to land in Southern France, first of the Seventh Army to cross the Moselle and first of the 36th Division to enter Germany.