Imagine you had Marty McFly's DeLorean DMC-12, a time machine that could transport you back to America in the mid-1960s. What would you see?

Lyndon Baines Johnson is the president. The United States is involved in a war on the other side of the world in a small country few Americans have heard of called "Vietnam." Cassius Clay (a.k.a. Muhammad Ali) is the heavyweight champion and behemoths from Detroit like the 4,500-pound Cadillac Sedan de Ville rule the road. Imagine also that you live in one of the industrial cities of Lake Erie like Buffalo, Cleveland, or Toledo.

Time out-of-mind, human beings have clustered around bodies of water like oceans, rivers and lakes. These bodies of water have provided a readily available source of food; a convenient transportation system for people and products and a variety of recreational opportunities. Some even hold a religious significance. There are rivers with names like "Ashtabula," which in the Lenape language means "always enough fish to be shared around." "Buffalo" is said to have come from the French expression "beau fleuve" for "beautiful river." Then there is the meandering Cuyahoga from the Iroquoian for "crooked river."

With the advent of industrialization and urbanization came change and another more sinister use: many rivers and lakes became unregulated sewer systems.

Looking through the lens of our 1960's time machine, we see that industrial wastes from Detroit's auto plants, Toledo's steel mills, paper plants of Erie and color factories in Buffalo have helped turn Lake Erie into a cesspool. Agricultural runoff has added to the problem. Only 3 of 62 beaches along the United States' Great Lakes shoreline are classified as safe for swimming. Wading is perilous with as many as 30,000 sludge worms carpeting each square yard of lake bottom. Each day, over 120 municipalities fill Erie with 1.5 billion gallons of inadequately treated wastes, including nitrates and phosphates. And the rivers? Growths of algae suck oxygen from the water impacting valuable commercial and game fish like blue pike, whitefish, sturgeon and northern pike, almost wiping them out. Lake Erie and its tributaries are slowly dying by suffocation. Rivers whose names used to reflect natural attributes now carry monikers associated with their new status. The Cuyahoga, for example, is known as "the river that burns."

2012 marks the 40th anniversary of the Clean Water which significantly expanded the role of the federal government from that of the Federal Water Pollution Control Amendments of 1948. The Clean Water Act established the goals of eliminating releases of high amounts of toxic substances into water, eliminating additional water pollution by 1985, and ensuring that surface waters would meet standards necessary for sports and recreation by 1983.

Section 404 of the Clean Water Act is also the authority under which the Corps of Engineers exercises jurisdiction over discharge of dredged or fill material in waters of the United States, including wetlands. The Act and its amendments mark a new and important chapter in terms of environmental protection; however, as important as this legislation is, there is a human component to the story that needs to be told.

Laws by themselves are only words on paper. The real story deals with what solders call "boots-on-the-ground," citizens who took it upon themselves take a stand, to become environmental activists before that term even existed. It is fitting, therefore, that on this 40th anniversary of the Clean Water Act we recognize Stanley "Stan" Spisiak. Who is Stan Spisiak? President Lyndon Johnson knew who he was. Thanks to his niece Jill Spisiak-Jedlicka, Executive Director of Buffalo Niagara RIVERKEEPER, Stan's story can be told.

Stanley P. Spisiak (1916-1996) was the 15th of 16 children of Polish immigrants. He grew up near Red Brook, a small tributary about 10 miles upstream from the mouth of the Buffalo River. As a young boy, he would lay along the banks of the Buffalo River, "watching the Spot-tail dace swim around."

Stan, an orphan at 16, went into the jewelry business with the sum of $1.96. Selling jewelry was his livelihood; it was not his life. For Stan, environmental alarm bells had been going off since the 1930s. He first became involved in preserving the Lake Erie's resources when he protested against the dredges that used to flock to Buffalo to suck up the sand off Woodlawn Beach where he swam as a boy. With the help of a local assemblyman Stan was able to put an end to the dredging.

What of Stan's beloved Buffalo River? It had degraded into one of the most polluted rivers in America. In 1968, the United States Department of the Interior described it as, "a repulsive holding basin for industrial and municipal wastes. It is devoid of oxygen and almost sterile." In 1969, the Buffalo River was declared "dead." In 1987, the river achieved the dubious distinction of being listed as a "Great Lakes Area of Concern."

For over 50 years, Stan, "Mr. Buffalo River," not only fought for the Buffalo River, but the Niagara River and Lake Erie as well. He became chairman of the Water Resources Committee of the New York State Conservation Council and received the presidential "Water Saver of the Nation" award.

As you can imagine, Stan was not popular with some politicians and industrialists. He literally pursued polluters and was reportedly even shot at. According to an article in Sports Illustrated, Stan began carrying a pistol "after part of his nose was torn loose from his face by two thugs who had been hired to throw him down the stairs after one of his speeches."

Stan's greatest achievement, beyond grassroots advocacy, left an indelible mark on the United States: he was instrumental in changing our national environmental policy. How, you may ask, is it possible for one man to do such a momentous thing?

After receiving the "Water Conservationist of the Year" award from the National Wildlife Foundation in 1966, Stan met with a lifelong advocate for beautifying the nation's cities and highways. Her motto was, "Where flowers bloom, so does hope." This woman, Claudia Alta Taylor, also happened to be the wife of a VERY powerful man. Claudia was better known to the American people as "Lady Bird Johnson." Stan invited Lady Bird to Buffalo for a personal tour of the Buffalo River. Here's what happened.

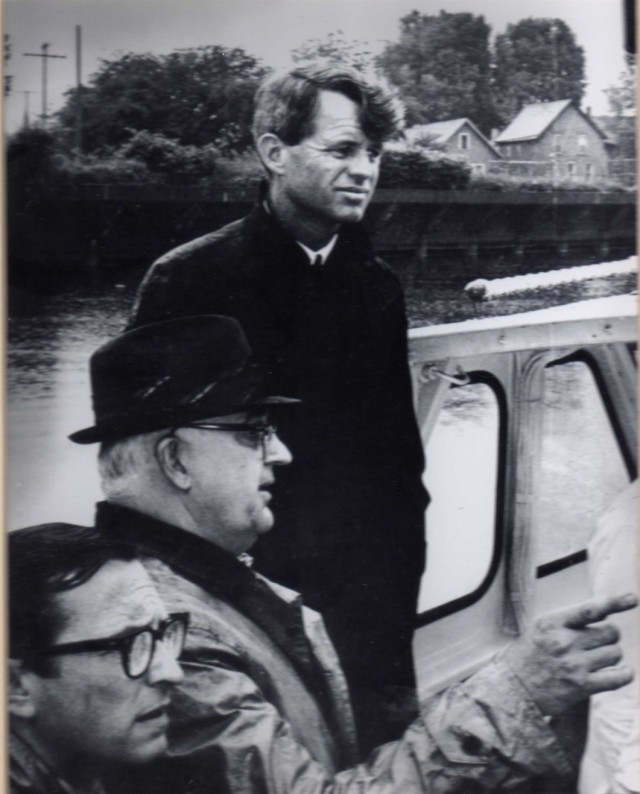

On August 25, 1966, Lady Bird not only showed up with President Johnson and then New York Governor Nelson Rockefeller, but a host of VIPs. Stan recounted, "President Johnson was my guest for three-and-a-half hours. I showed him a bucket of sludge from the Buffalo River and gave him a big spoon to stir it with." LBJ's words to Stan were simple and right to the point: "Don't worry. I'll take care of it." And he did.

Two weeks later, President Johnson signed an Executive Order banning open-water placement of polluted dredged sediment in Lake Erie, a restriction that endures to this day. Over the next few years, the Corps of Engineers embarked on an ambitious program to build "Confined Disposal Facilities" throughout the Great Lakes to safely contain polluted sediment dredged from waterways.

Let's get back in our time machine and move forward to August 16, 2011.

It is a beautiful summer day in Buffalo. A crowd gathers at a place along a revitalized section of waterfront known as "Canalside," an area built in 1825 as the western terminus of the Erie Canal. They are guests of the Buffalo River Restoration Partnership, a multi-agency team that includes the Corps of Engineers; the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency; the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation; Buffalo Niagara RIVERKEEPER and Honeywell, Inc.

The Partnership is working to remediate the Buffalo River thereby delist it as a Great Lakes Areas of Concern. Among the VIPs are: Cameron Davis, Senior Advisor to the Administrator, U.S. Environmental Protection Agency; Rep. Brian Higgins, 27th New York Congressional District; Hon. Byron H. Brown, Mayor, City of Buffalo; Lt. Col. Stephen H. Bales, commander of the Corps of Engineers, Buffalo District; Canadian Consul Marta Moszczenska; State Senator Tim Kennedy; representatives from the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation and officials from Honeywell, Inc. Jill Spisiak-Jedlicka, Stan's niece and Director of Ecological Programs, Buffalo Niagara RIVERKEEPER, proudly stands in this assemblage, albeit with her leg in a cast. Local media outlets are all present, jockeying for the best angle. So are a number of key stakeholders and ordinary citizens curious to see what all the excitement is about.

As the event unfolds and the words of speakers waft through the air, an ethereal form can be seen standing at a nearby railing, gazing up the Buffalo River--a young man about 16 years old, dressed in clothing from a bygone era. He turns towards the woman at the podium, smiles and shakes his head as he notices the cast, and utters a single word in Polish: Dziekuje --"Thank you."

Social Sharing