WASHINGTON (Army News Service, Feb. 22, 2008) -- During the final allied offensive of the Korean War, Master Sergeant Woodrow Wilson Keeble risked his life to save his fellow Soldiers. Almost six decades after his gallant actions and 26 years after his death, Keeble will be the first full-blooded Sioux Indian to receive the Medal of Honor.

The White House announced Friday morning that Keeble will receive the Medal of Honor posthumously in a ceremony scheduled for 2:30 p.m. March 3.

Keeble is one of the most decorated Soldiers in North Dakota history. A veteran of World War II and the Korean War, he was born in 1917 in Waubay, S.D., on the Sisseton-Wahpeton Sioux Reservation, which extended into North Dakota. He spent most of his life in the Wahpeton, N.D. area, where he attended an Indian school. In 1942 Keeble joined the North Dakota National Guard, and in October that year, found himself embroiled in some of the fiercest hand-to-hand combat of World War II on Guadalcanal.

Guadalcanal

"Guadalcanal seemed to be on his mind a lot," Russell Hawkins, Keeble's stepson, said. "His fellow Soldiers said he had to fight a lot of hand-to-hand fights with the Japanese, so he saw their faces. Every now and then he would get a far-away look in his eyes, and I knew he was thinking about those men and the things he had to do." At Henderson Field on the South Pacific Island, Keeble served with Company I, 164th Infantry - the first Army unit on Guadalcanal.

"I heard stories from James Fenelon, who served with him there, and he would talk about how the men of the 164th rallied around this full-blooded Sioux Indian whose accuracy with the Browning Automatic Rifle was unparalleled," Hawkins said. "It was said he would go in front of patrols and kill enemies before his unit would get there."

The Sioux have a word for that kind of bravery, according to Hawkins - wowaditaka. "It means don't be afraid of anything, be braver than that which scares you the most." Keeble personified the word according to fellow Soldiers, and earned the first of four Purple Hearts and his first Bronze Star for his actions on Guadalcanal.

Korea

Keeble answered the call to arms again when war broke out in Korea. He was a seasoned, 34-year-old master sergeant serving with 1st Platoon, Company G, 19th Infantry Regiment, 24th Division.

According to eyewitness accounts, while serving as the acting platoon leader of 1st Plt. in the vicinity of the Kumsong River, North Korea, on or about Oct. 15. 1951, Keeble voluntarily took on the responsibility of leading not only his platoon, but the 2nd and 3rd Platoons as well.

In an official statement 1st Sgt. Kosumo "Joe" Sagami of Co. G said, "All the officers of the company had received disabling wounds or were killed in action, except one platoon leader who assumed command of the company." The company's mission was to take control of a steep, rocky, heavily fortified hill.

Hawkins recalled how the man everyone knew as "Woody," described the terrain. "We were driving through Colorado on a trip, and Woody was pointing at something out the window," Hawkins said. By that time, Keeble had suffered seven debilitating strokes and lost the ability to speak.

"I pulled over and realized he was pointing at a large, rocky cliff with an almost sheer drop. I asked Woody if that was what it was like during that battle in Korea and he nodded, 'yes,'" Hawkins said. "It wasn't quite a straight drop down, but you could get up the hill faster on your hands and knees than on your feet."

Sagami wrote that Keeble led all three platoons in successive assaults upon the Chinese who held the hill throughout the day. All three charges were repulsed, and the company suffered heavy casualties. Trenches filled with enemy soldiers, and fortified by three pillboxes containing machine guns and additional men surrounded the hill.

Following the third assault and subsequent mortar and artillery support, the enemy sustained casualties among its ranks in the open trenches. The machine gunners in the pillboxes however, continued to direct fire on the company. Sagami said after Keeble withdrew the 3rd platoon, he decided to attempt a solo assault.

"He once told a relative that the fourth attempt he was either going to take them out or die trying," Hawkins said.

"Woody used to tell people he was more concerned about losing his men than about losing his own life," he added. "He pushed his own life to the limit. He wasn't willing to put his fellow Soldiers' lives on the line."

Armed with grenades and his Browning Automatic Rifle, Keeble crawled to an area 50 yards from the ridgeline, flanked the left pillbox and used grenades and rifle fire to eliminate it, according to Sagami. After returning to the point where 1st Platoon held the company's first line of defense, Keeble worked his way to the opposite side of the ridgeline and took out the right pillbox with grenades. "Then without hesitation, he lobbed a grenade into the back entrance of the middle pillbox and with additional rifle fire eliminated it," Sagami added.

Hawkins said one eyewitness told him the enemy directed its entire arsenal at Keeble during his assault. "He said there were so many grenades coming down on Woody, that it looked like a flock of blackbirds." Even under heavy enemy fire, Keeble was able to complete his objective. Only after he killed the machine gunners did Keeble order his men to advance and secure the hill.

"When I first started hearing these stories I was amazed that a man of Woody's size (more than six feet tall and 235-plus pounds), could sneak up on the enemy without being noticed," Hawkins said. "So one day, I was out helping him mow the lawn, and I asked him how he did it. He just shrugged his shoulders.

"I joked with him and told him those soldiers must have been blind or old or something, because he would never be able to sneak up on a young guy like me." Hawkins said he continued to mow then was startled when Woody popped up from behind some bushes near him. "He could have reached out and grabbed me by the ankles, and I didn't even know he was there!" Keeble had slid on his back behind the brush. Although Hawkins was not positive, he believed Keeble might have used a similar maneuver when attacking the pillboxes.

Keeble's selfless acts on that rugged terrain in 1951 did not come without a price. According to Sagami and other eyewitnesses, he was wounded on at least five different occasions by fragmentation and concussion grenades. "His wounds were apparent in the chest, both arms, right calf, knee and right thigh and left thigh." Sagami cited blood at the wound locations as evidence.

Hawkins said 83 grenade fragments were removed from Keeble's body, but several others remained. "You could tell that the wounds bothered him sometimes, but he never complained."

Sagami wrote in his statement that Keeble did not complain on the battlefield either. "At no time did he allow himself to be evacuated during the course of the day. Only after the unit was in defensive positions for the night did he allow himself to be evacuated."

According to Hawkins, every surviving member of Co. G signed a letter recommending Keeble for the Medal of Honor on two separate occasions, once in November 1951 and then again in December that same year. On both instances, the paperwork was lost. Keeble was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross Dec. 20, 1952 for his actions in Korea, not the Medal of Honor his men believed he deserved. He also earned the Purple Heart (First Oak Leaf Cluster); Bronze Star (First Oak Leaf Cluster); and the Silver Star as a result of his heroics throughout his tour in Korea. He was honorably discharged March 1, 1953.

Life after the Army

Even after his discharge, Keeble never severed his ties with the Army, Hawkins said, and was a champion for veterans and their causes. "He was always going to different veterans events and he supported the Disabled American Veterans organization. He would wear his uniform in parades, and was the first in line for any type of fundraiser."

Though Keeble knew of his unit's failed attempts to award him the Medal of Honor, Hawkins said he never sensed any bitterness from him. "Whenever someone would bring it up, he just shrugged. He wasn't there to get medals; he was there for his men and his country. He enjoyed the small things in life, and concentrated on what he had, not what he didn't have."

Those who didn't know Keeble the Soldier saw him as a kind-hearted, gentle man full of humility, according to Hawkins. "Woody was a very upbeat person. If you didn't know his war record, you'd think he was just a happy-go-lucky guy. His glass was always half full, never half empty."

In later years, Keeble fell on hard times and was forced to pawn all his medals. He had one lung removed, and in the months and years following the surgery suffered more than a half dozen strokes that Hawkins said eventually left him speechless. "But his mind remained sharp, and he was the same man inside."

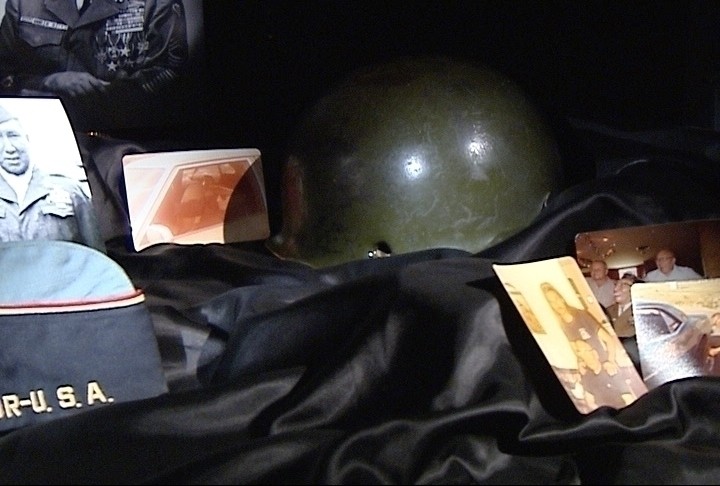

Keeble's family was presented with a duplicate set of medals in May 2006, and they, along with his uniform and other memorabilia, are housed at the University of North Dakota in Grand Forks.

Long Road to Medal of Honor

The family's battle to upgrade Keeble's Distinguished Service Cross to the Medal of Honor began in 1972, when both Woody and his wife, Dr. Blossom Hawkins-Keeble, were still alive. According to Hawkins, the family unknowingly started off in the wrong direction. "We thought the paperwork had been lost, but were unaware that it no longer existed. It didn't just get lost on the battlefield, it never made it off the battlefield." When the family finally realized this fact, they sought the support of the Sisseton-Wahpeton tribe and gathered recorded statements from the men who served with Keeble.

The team soon learned that since the statute of limitations for awarding the Medal of Honor was three years from the date of the heroic action, it would literally take, "An Act of Congress," to realize the goal. Beginning in 2002, the tribe involved senators and representatives from North and South Dakota. Armed with written evidence, eyewitness accounts and letters from four senators supporting the effort, tribe officials contacted the Army, which reviewed the evidence and concluded Keeble's actions were worthy of the medal. Finally, on March 23, 2007, North Dakota Senator Byron Dorgan introduced a bill, cosponsored by Senators Kent Conrad (ND), Tim Johnson (SD) and John Thune (SD), authorizing the president, "To award the Medal of Honor to Woodrow W. Keeble for his acts of valor during the Korean conflict." Congress passed the bill in early December 2007.

Hawkins will represent Keeble in a White House ceremony March 3, where he will accept the Medal of Honor on his behalf.

"We are just proud to be a part of this for Woody," Hawkins said. "He is deserving of this, for what he did in the Armed Services in defense of this country."

Hawkins added that this victory is as important for the Sisseton-Wahpeton tribe and North and South Dakota as it is for Keeble and his family. "We are all extremely proud that Woody is finally receiving this honor. He epitomized our cultural values of humility, compassion, bravery, strength and honor."

He added that Woody was the embodiment of "woyuonihan," or, "honor," always carrying himself in a way so that those who knew him would be proud of him. "He lived a life full of honor and respect."

Hawkins said his feelings about Keeble echo those of all who knew him. "If he was alive today, I would tell him there's no one I respect more, and how he is everything a man should be: brave, kind and generous. I would tell him how proud I am of him, and how I never realized that all this time, I was living with such greatness."

Social Sharing