In the Middle Ages, knights-whose view of the battlefield was limited to what they could see through tiny slits in metal helms-recognized the need to be able to better identify friend from foe. Rather than clatter around the battlefield and hope they were fighting the right person, the knights decided to create a system of identification. So, the knights painted their shields with the colors and symbols of their clans or fiefdoms.

Thus, heraldry was born.

However, traditional heraldry did not exist in the U.S. officially until 1957, when Public Law 85-263 was signed, allowing the secretary of the Army to provide heraldic services to all agencies within the federal government, Charles Mungo, director of The Institute of Heraldry, explained.

"This ultimately led to the creation of The Institute of Heraldry in September 1960," Mungo said.

On Sept. 15, 2010, TOIH celebrated its 50th anniversary. The institute held a symposium on heraldry in the U.S., explaining the institute's origins and current processes, as well as the relevance of heraldry in the military today.

When the colonists declared independence from Britain in 1776, heraldry was found in every aspect of European life; religious communities, trade guilds and aristocratic households alike had coats-of-arms, TIOH's website states.

To sever the United States from any associations with the monarchy and nobility, the Founding Fathers believed that honors, titles and privileges given to Europe's elite had no place in the new republic. For more than a century, the government and military had no centralized authority to register, record or regulate the design and use of military symbols, or insignia.

But during World War I, President Woodrow Wilson considered having the wide variety of insignia present in the military cataloged.

"He confided in the secretary of war at the time to see if he could create a heraldic program office that would oversee the development of insignia for the Army," Mungo said. "So our roots were very Army-centric, and we were created just to oversee the development of the different types of insignia for the Army uniform."

In 1919, the first heraldic program office was created under the Army staff, Mungo said. When World War II began, the office expanded, providing heraldic services to all branches of the armed forces. That expansion continued until 1957, when the program office began providing services to all federal government agencies.

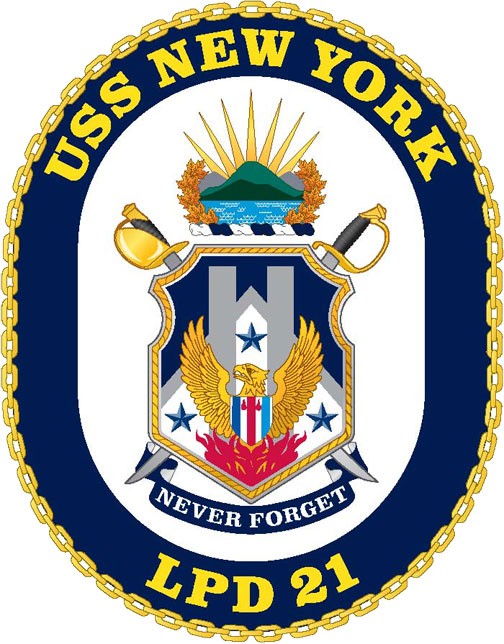

Today, TIOH designs heraldic symbols such as coats of arms, medals, flags, textile insignia, qualification badges, decorations and organizational seals. Their customer base includes the Office of the President of the United States and all federal agencies and branches of the military.

"Heraldry is a very narrow field of art," Mungo said, "and there are not many schools or institutions that really study the art of heraldry, so a lot of what we do resident here is the only agency in the federal government that has this kind of knowledge base."

The institute has three divisions, each playing a key role in the design and maintenance of heraldic items.

The Heraldic Services and Support Division is in charge of project management, research, library maintenance, some policy maintenance and website administration, said Petra Casipit, chief. This division keeps the heraldic work flowing seamlessly and answers questions from the public and various agencies about heraldry.

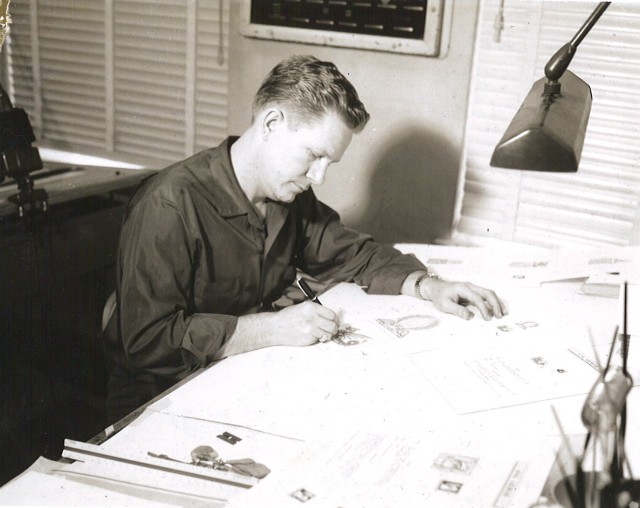

The Heraldic Design Division, run by Pamela Madigan, conceptualizes and designs heraldic symbols, from shoulder sleeve insignia and streamers to coats-of-arms and flags.

There are basically three ways of designing an image, Madigan said. Sometimes, people will approach them with an idea of what they want, possibly even a sketch, and the design division helps them finalize the design and makes sure colors and metals are finished appropriately.

Sometimes, the designs are already finished and the unit or agency just needs TIOH to manufacture the item. Other times, there is no design idea and the division must conceptualize the item in coordination with the client, Madigan explained.

The design division employs several illustrators. Some prefer to sketch ideas while others prefer to work entirely on the computer, but all agree that developing a heraldic item takes artistic precision and careful research.

"You have to be able to draw and design," said Costella Alford, illustrator. "It's a big part of what we do."

Sarah Leclerc, another illustrator, added, "You're hired as an artist, but you have to learn the language of heraldry, which means that you have to (read different books on heraldry). It all has its own language."

Leclerc enjoys her job, one she says allows her to see the fruits of her labor, whether in the shoulder sleeve insignia on a Soldier or on a crest.

In addition to traditional heraldic designs, the division also manufactures general officer certificates.

"We do calligraphy here; we do general officer certificates," Madigan said. "There's a hand done certificate that states (congratulations) on their promotion from the office of the president and signed by the secretary." Only between eight and 10 of those certificates are produced a year, and TIOH only makes them for the Army. The other services make their own.

Thomas Casciaro's Technical and Production Division is responsible for manufacturing requirements. Anything that needs to be made comes through this division.

"I have an industrial specialist for medals, and industrial specialist for textiles," Casciaro said, "Depending on what it is, it will go to one or the other. Then, we will develop a purchase description of what we want and then we will work with one of our certified manufacturers," to produce the item.

The production division is also responsible for the manufacturing certification program, Casciaro explained, which involves a six-month certification process under Army Regulation 672-8 and the Code of Federal Regulation Title 32. During the process, a demonstration package is sent out, and the manufacturer is required to reproduce the item in the package and return it to TIOH.

Casciaro's division then inspects the samples for quality and ensures the item can be made to the institute's standards. Once the manufacturing certification is complete, it lasts for five years.

This division maintains the "cartoons," or textile blueprints, for insignia. "They're huge. They're like 50 times the actual size, but it shows exactly where every stitch goes, how many stitches there are, and what type of stitch," Casciaro said. "An average shoulder sleeve insignia is eight or nine thousand stitches."

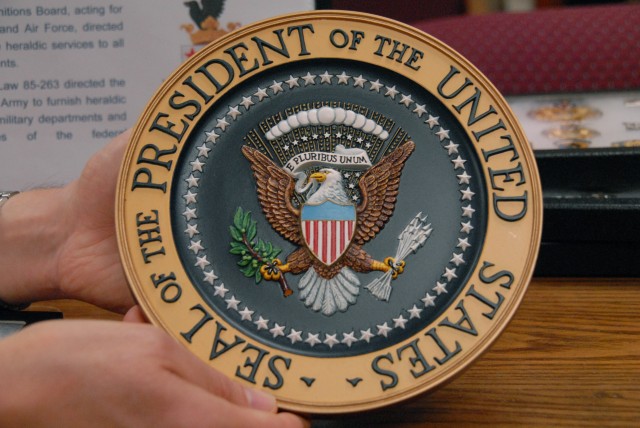

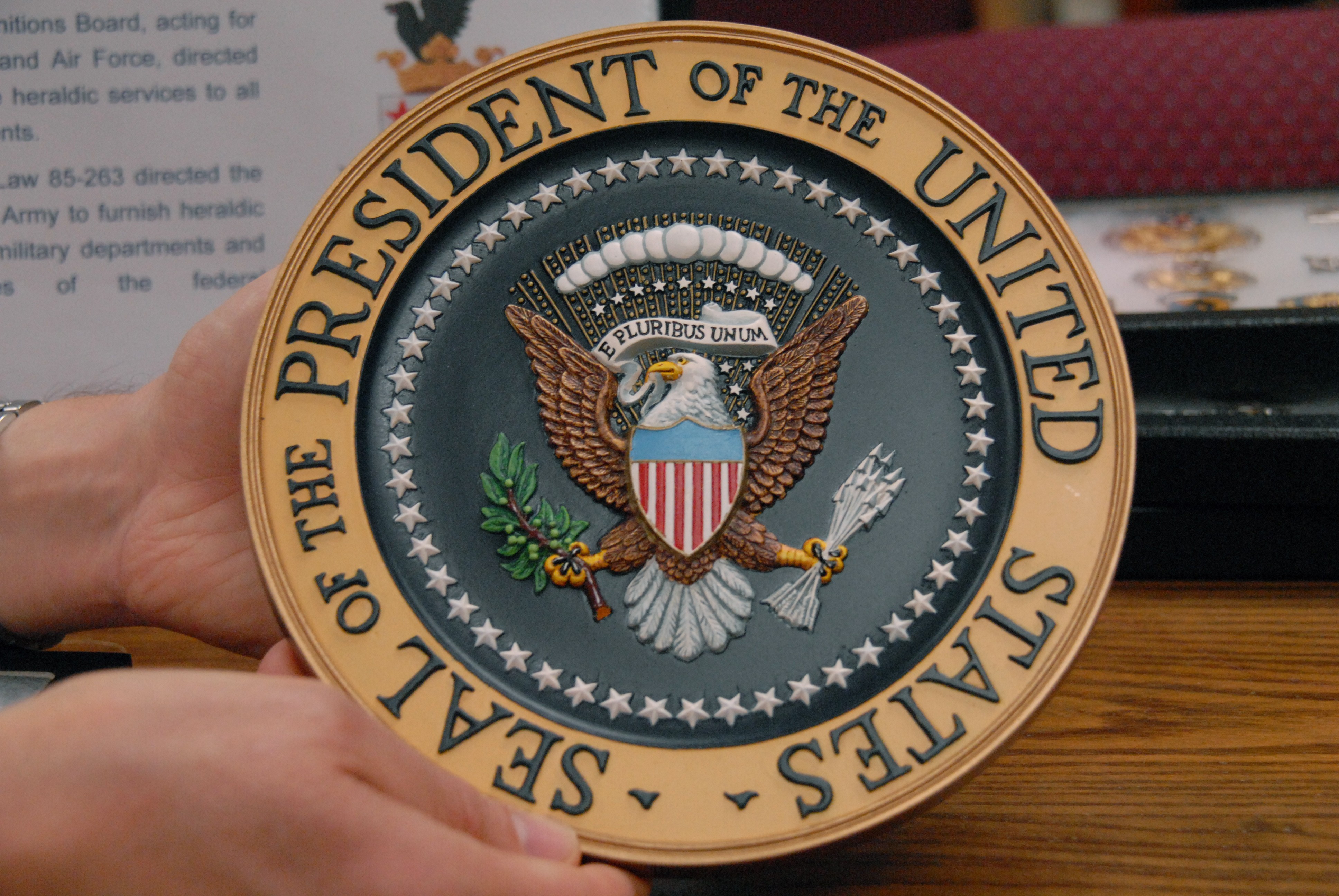

Presidential seals and other official plaques are made and maintained through the production division, as well. Rhonda Reiner and Michael Craghead, cast, paint and repair seals-which can be delicate and painstaking work.

"To make a plaque it takes about a week, because we fabricate them and then we paint them," Reiner explained.

To clean and repair a small seal or plaque takes an average of four hours, because the work is so delicate, Reiner said. She carefully scrapes away dirt and repaints them before applying a clear varnish.

A finished plaque is kept at TIOH for reference.

"That's why we have a lot of these," Craghead said. "If they ever wanted a duplicate we'd have all the colors right in front of us."

The biggest current project in the technical division is converting all the textile shoulder insignia to combat service identification badges for the new Army Service Uniform, Casciaro said. The division tries to convert about 100 insignia a year and they exceeded that goal for 2010.

"These are a hot item right now with the Soldiers. Everybody wants their badge now," he said.

For half a century, through ever increasing and evolving demands, TIOH has continued to adhere to the highest standards for manufacturing and maintaining heraldic items. The institute's men and women are honored to preserve the attention to detail and strict quality controls required to support an evolving Army.

"I'm very proud to be here at the time of the 50th anniversary," Mungo said. "That milestone is pretty exciting."

Social Sharing