THE Forensic Analysis Division at the U.S. Army Criminal Investigation Laboratory at Fort Gillem, Ga., is extensive, comprising seven analytical areas. Most are the usual things you might think about when you think of forensics: DNA, trace evidence, drug chemistry, latent prints and firearms and toolmarks.

'However, two areas don't immediately come to mind: forensic documents and digital evidence.

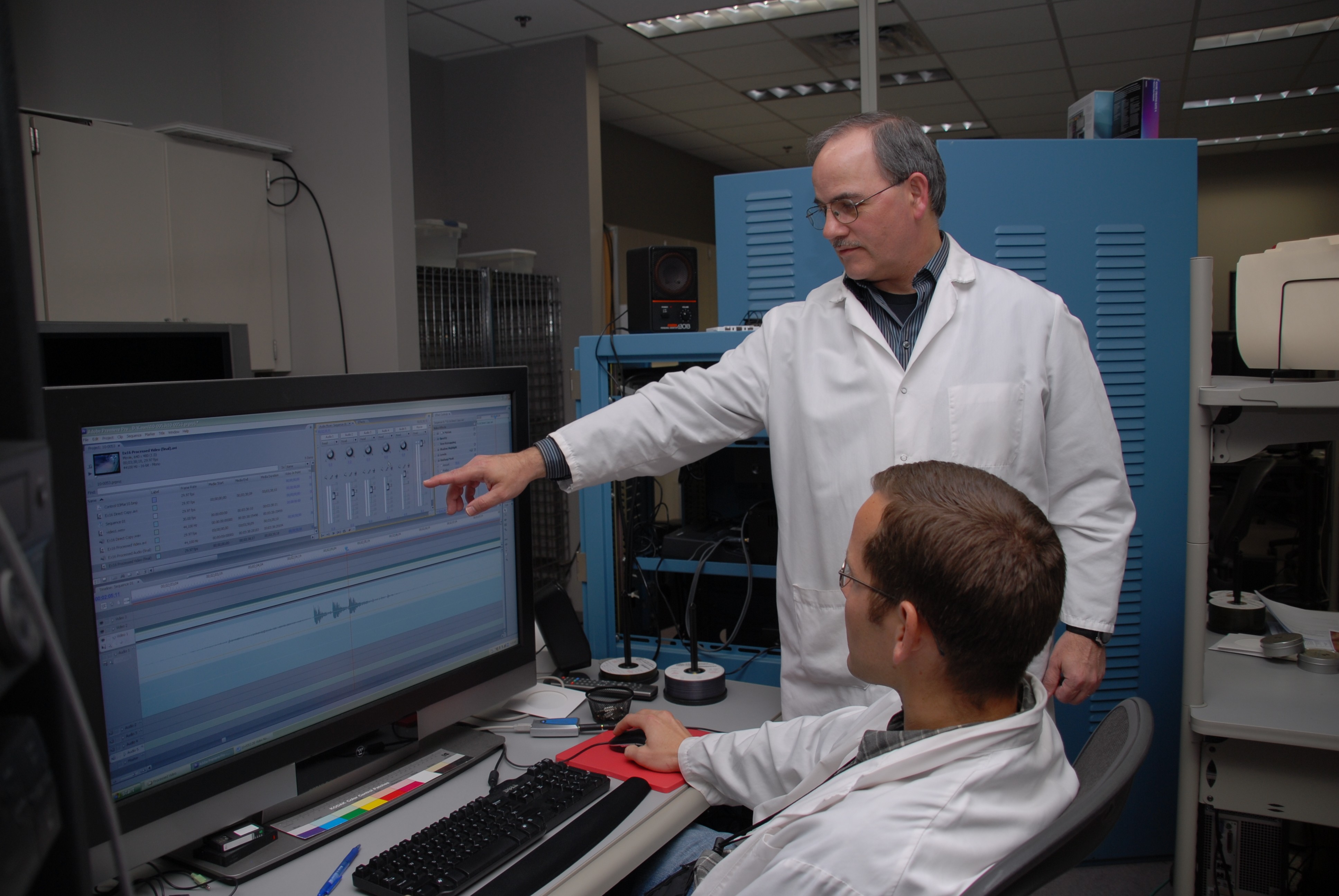

'The Digital Evidence Branch analyzes computers, mobile phones, e-mails, video and photos for CID and all other military law enforcement agencies, David Deitze, branch chief, explained. It's divided into three main sections: photographs or imaging, which is what the branch has historically focused on, computer forensics, and audio/video enhancement.

'About 50 percent of our work here is (related to) child pornography, 20-25 percent is (related to) sexual assaults, and the rest consists of fraud, larceny, suicide-anything that is an offense in the military,' Dietze said of the variety of cases that come through the branch from across the services.

'Everything that comes into the branch is copied onto 'sterile media' (a wiped hard drive or blank digital storage device), during the analysis process, so cases won't be mixed up. Once on the sterile media, the analysts perform string searches with terms that are indicative of the case being worked, and the computer will pull up matches, Dietze explained. The matches are examined and the results burned onto a disk, to be sent back to the special agent or prosecutor.

'Often it takes weeks or months to process digital evidence, due to the volume of information. One case the branch is working has 16 terabytes of data, Dietze said.

'Each of our sections has specialized training. The imaging section is a two-year course, the audio/video enhancement is a two-year course, and (computer forensics) is a one-year course,' Dietze said. 'We generally hire people, especially into this section, that already have certification in computer forensics.'

'In the audio/video section, analysts process evidence using new digital techniques to make images clearer, and authenticate evidence to ensure it wasn't altered, Carl Kriigel, team leader, explained.

'Christina Malone, a digital-evidence trainee, explained that her section analyzes photographic comparisons and image alterations, looking for inconsistencies in the image, perspective, pixel size, or the direction of light.

'One of the fancier things we have now is the 3-D scanner,' Malone said. The scanner uses a laser grid to determine how far objects are from the scanner, creating a three-dimensional image.

'This tool is primarily used for documenting crime scenes, but can also be used for blood-spatter interpretation measurements, Dietze said.

'Another useful tool in the imaging section is the military uniform uniqueness statistical estimator, which detects pattern matches in military uniforms, and uses statistics to determine the likelihood of that portion of a pattern appearing in a specific place on a uniform, Malone said. The tool will match the pattern sample to a database, and trace it to a suspect.

'Uniform patterns are seemingly random, much like handwriting, but an expert eye and a little help from a good tool go a long way, Malone added.

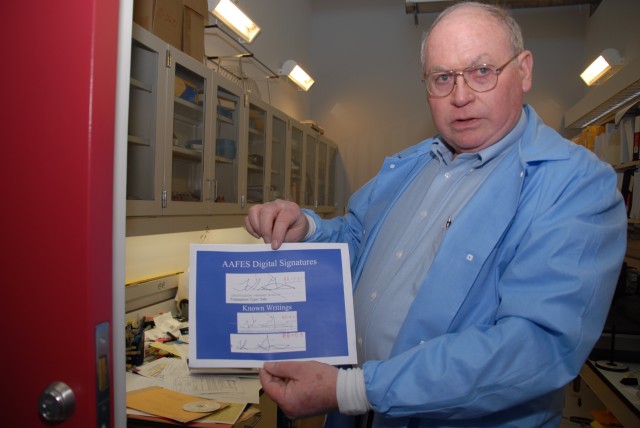

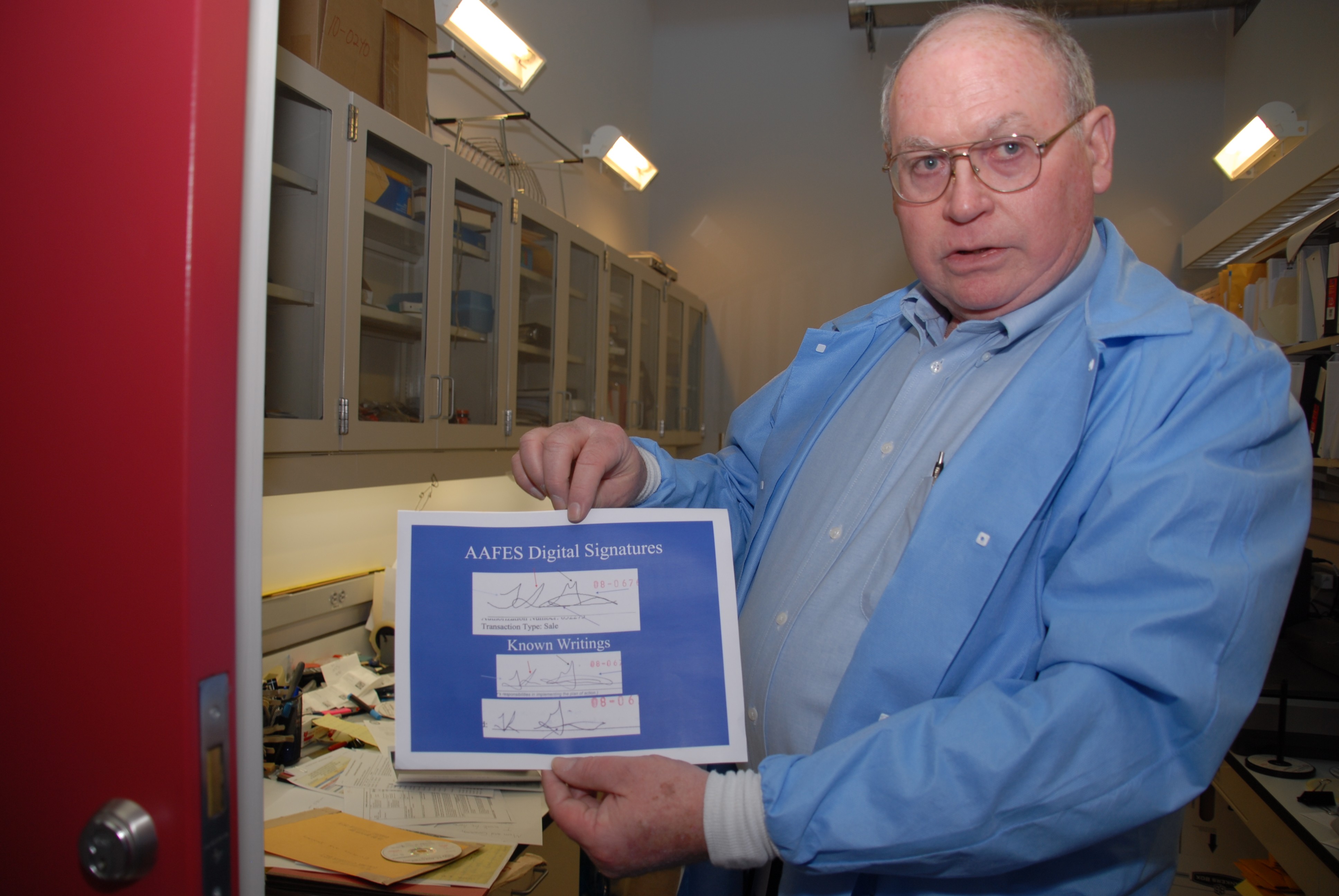

'The Forensic Document Branch conducts mostly handwriting analysis, Joseph Parker, division chief, explained.

'We don't tell personalities from handwriting, nor do we believe that it can be done,' Parker cautioned. "The research that has been done on that shows that there is no consistency in the results...we only work for identification of someone.'

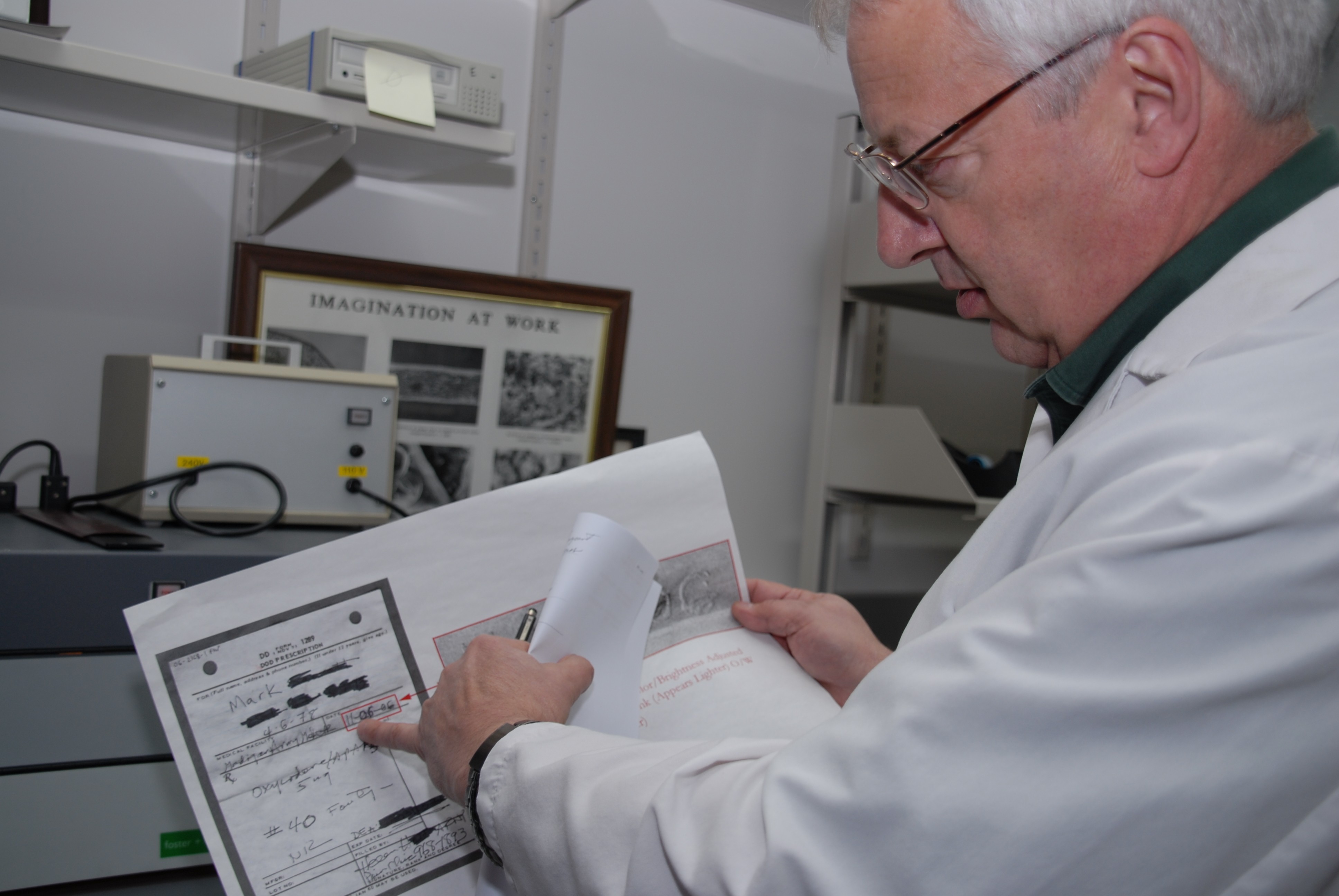

'A good portion of the analysis the branch conducts is forgeries, like altering medical prescriptions, but they also analyze other writing samples, such as suicide notes. Handwriting-analysis training is extensive; the program takes full-time students a minimum of two years to complete. The students look at tens of thousands of writings, Parker said, and discuss them with experienced examiners "so they can learn what's important and what's not important for identification or elimination purposes.

'What we're doing is subjective, I have to convince the judge and the jury that I know what I'm doing, and here's why,' Parker added.

'The most effective tool at the division's disposal is its people. 'Most of our work, particularly for handwriting, occurs between our ears,' Parker said.

'Academic research conducted over the past several years has supported as much, indicating that when there are two examiners, one reviewing the work of the other, the resulting error rate is close to zero, he added.

'Jerry Gayle, forensic-document examiner, explained that handwriting is made unique by small changes in letters individuals accumulate over time, as writing becomes more of an innate process.

'These characteristics accumulate, and by the time a person becomes an adult it's habit, and it's the totality of these characteristics that makes writing identifiable,' Gayle said.

'Most of the obvious writing characteristics are the way letters are formed, slant of the writing, and so forth, Gayle said. Some of the less obvious characteristics are 'I' dots and 'T' crossings, the upper and lower extenders, and internal proportions of tall letters to the main body of the handwriting.

'No one of those characteristics like that is sufficient for identification, but taken together, enough uncommon characteristics make it possible to identify a person's handwriting,' Gayle said.

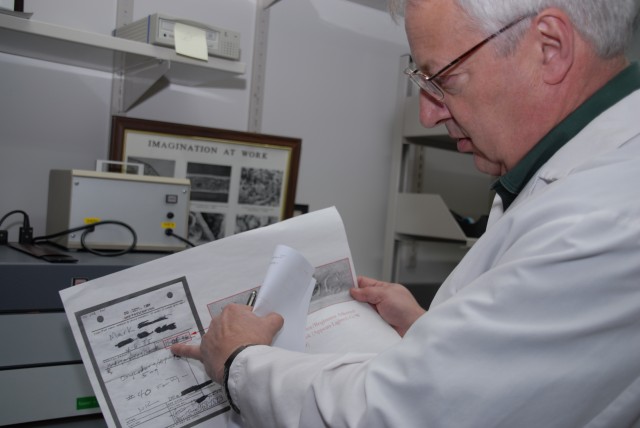

'To conduct an examination, investigators compare a collection of known writings (writings known to be by the subject), and a collection of questioned writings.

'During the examination process we sit down and we go through the questioned and known handwriting letter by letter, comparing it to see if matching characteristics are found, or if characteristics are found that are distinctly different,' Gayle explained.

'We have a range of conclusions of different strengths to describe the strength of evidence that we found, and of course, in some cases, for varying reasons, we can't reach a conclusion at all. And that's one of our conclusions, that the person could neither be identified or eliminated,' he added.

'The human eye does most of the handwriting examinations, but examiners also employ stereomicroscopes to look at details in the ink line, Gayle explained.

'Despite the subjective nature of handwriting analysis, it can be very effective if the examiner is well trained, Parker said.

'While forensic document analysis and computer forensics may not seem as glamorous as some of the other disciplines within CID, they are integral parts of the organization, providing valuable information and insight to investigators.

Social Sharing