Army Aviation developed rapidly during World War I with significant advancements in aircraft types, weapons, ordnance, instruments and flight gear, including parachutes. Initially, parachutes were developed primarily for balloon observers who were forced to jump from their observation baskets when attacked. Unfortunately, early parachutes were too heavy and bulky for most small aircraft and many pilots perished in their burning aircraft grimly nicknamed "flaming coffins"

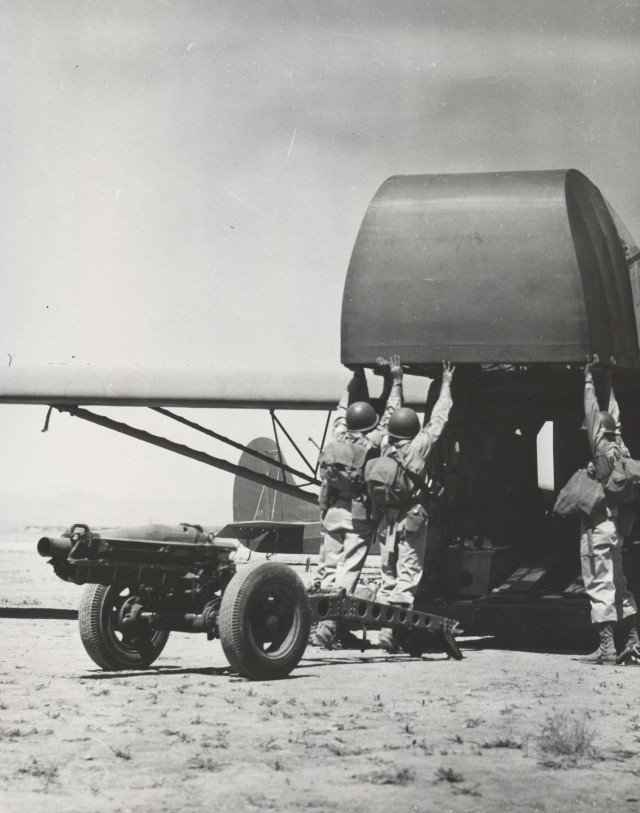

As aircraft developed during the interwar period, military planners also experimented with parachutes both to save lives and to insert troops into combat. Gliders were also developed to deliver troops, artillery and supplies. The outbreak of World War II in 1939 provided an opportunity to implement and refine airborne doctrines. The German military had some notable early airborne successes in Norway, Belgium and Crete; lessons not lost on Army planners.

Recognizing the potential of airborne forces, the Army moved to create airborne units shortly before America's entry into World War II. A test platoon was formed in June 1940 to help develop airborne tactics and equipment. The 82nd Infantry Division was redesignated and the 101st was activated on 15 August 1942 as the Army's first two airborne divisions. The 11th, 13th and 17th Airborne Divisions were activated by 1943. A typical airborne division included a mix of parachute and glider infantry regiments, with artillery, engineer and support units.

Planning for the first large-scale airborne assault in Army history, the invasion of the Italian island of Sicily, was led by Major General Matthew B. Ridgway, commanding the 82nd. Codenamed Operation Husky, the invasion had the strategic goals of removing the Axis base, which operated against Allied shipping in the Mediterranean, and pressuring the Italians to exit the war. The joint operation of United States, British and Canadian air, land and naval forces began with four airborne drops, two British and two American, shortly after midnight on the night of 9 -10 July. The American contingent was primarily the 505th Parachute Infantry Regiment, 82nd Airborne Division, making its first combat jump. Adverse winds impacted the drops, and only about half of the airborne force reached their assigned positions. Although scattered, the paratroopers disrupted German and Italian patrols and communications, thereby drawing away some enemy assets from the conventional ground forces.

Unfortunately, poor communications among the Allies led to a tragic friendly fire incident on 11 July. Antiaircraft gunners on Allied ships who were jumpy from German air attacks misidentified American aircraft flying a reinforcement mission, and thirty-three of the 144 C-47 transports were shot down for a loss of over 300 paratroopers. Despite these losses Sicily eventually fell to the Allies on August 16th. Combined with the loss of Libya and Pantelleria, and the July 19th bombing of Rome, the Sicilian campaign helped motivate a bloodless coup that deposed Italian dictator Benito Mussolini. Italy withdrew from the Axis in September and in due course even made some contributions to the Allied war effort.

The accomplishments and lessons learned during Operation Husky were applied in the planning for subsequent airborne assaults in the European and Pacific Theaters of Operation. Today, airborne units remain a potent force in the Army's land power capabilities.

Social Sharing