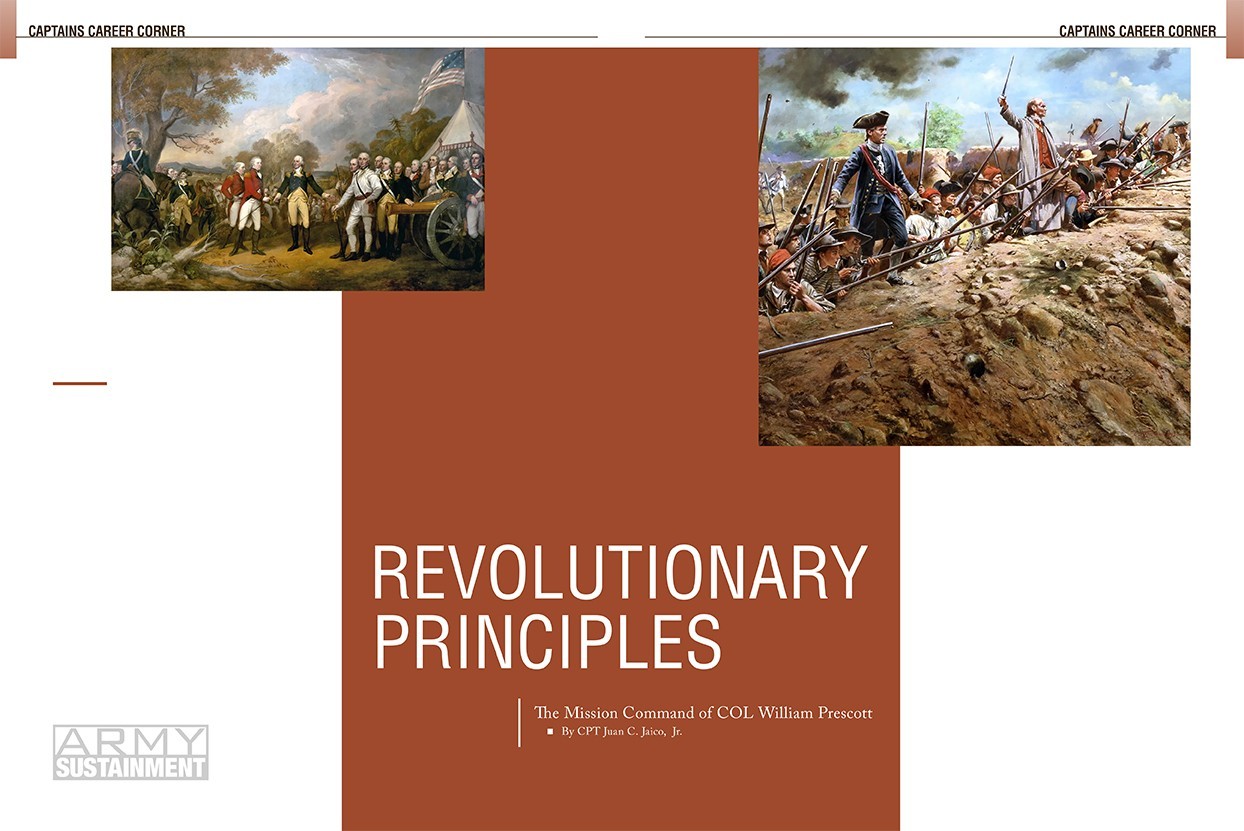

Right: Redoubt at the Battle of Bunker Hill, June 17, 1775. COL Prescott is accurately depicted in his long coat, minus his floppy hat he wore that day. (“Bunker Hill” By artist Don Troiani) VIEW ORIGINAL

Introduction

On June 17, 1775, the impact of British naval guns and the steady advance of seasoned troops threatened to shatter the colonial siege of Boston. Directing an effective engagement within a hastily improvised fortification on Breed’s Hill, COL William Prescott, commanding 1,200 Massachusetts militiamen armed with limited ammunition and raw resolve, seized the initiative by ordering, “Wait until you see the white of their eyes.” His leadership presence and clear directives under fire forged cohesion among the inexperienced militia.

In the span of three British assaults, the militia delivered coordinated, massed volleys that blunted the British attack and inflicted over 1,000 casualties on the enemy, reshaping British perceptions of colonial resistance in the early days of the American Revolution. Prescott’s actions exemplify how adaptive leadership and command principles can shape the tactical outcomes against a superior force. He successfully executed the mission command principles of competence, shared understanding, disciplined initiative, and risk acceptance.

History

William Prescott, born in Massachusetts in 1726, served in provincial militia campaigns during King George’s War in 1745 and the French and Indian War in 1755, earning recognition for field engineering and leadership. In 1774, Prescott was commissioned colonel of the Pepperell regiment of Minutemen, and in 1775, the Massachusetts Committee of Safety placed militia around Boston under the command of GEN Artemas Ward. On the night of June 16, 1775, Ward ordered Prescott to occupy Charlestown. The Charlestown peninsula showed two predictable landing sites: Copp’s Hill and the Mystic River shore, constraining British operational options and directing any assault into narrow corridors. Recognizing this, Prescott deliberately occupied Breed’s Hill to exploit its steep slopes and muddy flanks, which canalized enemy formations into predesignated kill zones. He also integrated lessons from earlier colonial skirmishes, adapting fortification techniques to the irregular militia.

Under the cover of darkness, he oversaw the construction of a 160-foot redoubt and connecting breastworks, then coordinated musket drills. Despite the chaos of construction at night, he organized sentries and rotating digging teams to maintain operational security and endurance. He inspected each sector, ensuring that the trenches and fortifications conformed to his design for effective engagement. British eyewitness accounts later noted the militia’s readiness at first light. This rapid fortification also sent a message that colonials were no longer content to besiege Boston but were prepared to seize the initiative and contest control of the high ground.

At dawn, British ships opened fire as Prescott moved among the works, adjusted barriers, and rallied Soldiers. After three assaults and a famous close-range volley, the exhausted militia withdrew to Cambridge, having inflicted heavy losses on the British forces at the cost of over 400 American casualties, a testament to effective defense and emerging colonial command proficiency.

Competence

Competence as defined by Army Doctrine Publication (ADP) 6-0, Mission Command: Command and Control of Army Forces, is “tactically and technically competent commanders, subordinates, and teams,” which are “the basis for mission command. An organization’s ability to operate using mission command relates directly to the competence of its Soldiers.” Prescott’s understanding of field fortifications, musketry, and small-unit leadership embodied competence and underpinned every decision.

His 30-year militia career began at age 17, serving at Louisbourg in 1745 and Fort Beausejour in 1755, where he perfected rapid entrenchment and coordinated volley fire. Drawing on this experience, he engineered a hexagonal redoubt 8 feet high on all faces, flanked by angled breastworks to deflect British fires and mask dead ground. Additionally, he supplemented his technical skills with hands-on training, such as demonstrating trench digging, followed by live-fire demos in adjacent fields so his militiamen understood the importance of volley timing and barrel alignment. This direct mentorship accelerated battlefield proficiency and exemplified leader presence as a force multiplier.

Prescott’s real-time corrections, such as shouting measured cadence commands and repositioning of muskets, ensured that even his inexperienced militiamen performed like seasoned troops at critical moments. His presence during battle also bolstered morale. Soldiers dug deeper, adjusted traverses, and prepared coordinated fire sectors. Without competent leadership, massed volleys would have lacked cohesion, and the redoubt might have collapsed under British cannon fire. This level of professional expertise fostered confidence among the militiamen, directly influencing their willingness to hold fire until the decisive moment.

Prescott’s engineering choices also reveal a solid grasp of terrain advantages on the battlefield. His proficiency ensured structural integrity and fire discipline. Transitioning from personal craft to the collective purpose, Prescott forged a shared understanding of intent, terrain, and mutual support across his inexperienced militiamen.

Shared Understanding

Shared understanding within the scope of ADP 6-0 is that of “an operational environment, an operation’s purpose, problems, and approaches to solving problems.” Prescott created a unified mental model through clear commander’s intent and aligning subordinate awareness of terrain and timing. He ordered company and platoon leaders to the redoubt’s edge, declaring the task as delaying the enemy by massed volleys at close range, conserving ammunition and protecting the flanks. He sketched likely landing beaches along the Mystic River and identified fire sectors for each unit. Throughout the night, lieutenants relayed these instructions to squads, rehearsing the volley rhythm that would occur at 50 yards.

By distributing hand-drawn terrain sketches to his lieutenants, Prescott created a common operational picture at the platoon level, mirroring today’s digital common operational picture that synchronizes situational awareness across echelons. Additionally, subordinate leaders marked firing points with entrenching tool handles, creating visual anchor points for untrained militiamen. On the battlefield, this shared understanding synchronized fire: when British troops charged through smoke into open ground, every musket erupted in a single, disciplined wave, scattering the first two assault columns.

Prescott’s clear intent and continuous reinforcement prevented piecemeal firing, absorbed the shock of naval and infantry pressure, and welded individual actions to a cohesive defense. Additionally, the rehearsal drills that occurred before execution refined volley timing and fostered mutual trust. By aligning the force cognitively, Prescott set conditions for decentralized adaptation; subordinates innovated local defenses without fracturing overall unity toward achieving the end-state.

Disciplined Initiative

ADP 6-0 defines disciplined initiative as “the duty individual subordinates have to exercise initiative within the constraints of the commander’s intent to achieve the desired end state.” Under Prescott’s clear intent, junior leaders exercised disciplined initiative. On the left flank, CPT Thomas Knowlton observed British infantry attempting a riverine landing. Remembering Prescott’s intent to channel attacks into kill zones, Knowlton ordered his men to create a section of rail fence, forcing the enemy column into a single file. Simultaneously, LT John Moore redirected a two-pound swivel gun to cover a gap in the fortification, firing into the enemy’s open flank. These autonomous measures relieved pressure on the center and slowed British envelopment, enabling the main fortification’s massed volleys to strike a compressed target. Moreover, CPT William Brodie established a sharpshooter position atop a collapsed wall on the right flank that enabled targeted fire on British officers. Additionally, SGT John Parker improvised a reserve volley line behind the main fortification when ammunition ran low in forward positions.

Prescott’s guidance provided the framework for local adaptations. Each platoon acted in concert with its overarching scheme, preserving ammunition and maintaining lethal effect. By trusting subordinate judgment, Prescott multiplied combat power without micromanagement. Having empowered initiative among junior leaders and subordinates, he then balanced opportunity with the calculated risk required to seize the high ground.

Risk Acceptance

ADP 6-0 demands recognition that operational risk can never be fully eliminated; commanders must weigh risk against potential gain. Prescott chose Breed’s Hill over the more defensible Bunker Hill. He considered terrain and the impact of directly challenging British naval dominance against the inherent risks. Prescott also evaluated alternative schemes, such as delaying fortifications until dawn, which risked exposure to naval bombardment, or reinforcing Bunker Hill, which lay beyond effective threat to the British fleet. He concluded that a nighttime operation on Breed’s Hill offered the optimal balance of risk and operational effect.

Another part of risk assessment is found in the quartermaster records, which indicate the militia stockpiled roughly 20,000 musket rounds, far fewer than a British infantry brigade’s daily expenditure. This forced Prescott to ration fire and meticulously plan volley sequences, which aligns with sustainment considerations in risk acceptance.

Prescott’s professional rapport with GEN Ward, honed during earlier service, afforded him the authority and latitude to conduct nighttime entrenchment without explicit approval. Although some council members feared naval counterfire, Prescott convincingly argued that a bold fortification at that location would disrupt British operations and bolster colonial morale before the winter siege.

Under the cover of darkness, Prescott’s militiamen worked under the arc of naval searchlights and the risk of discovery. Prescott’s acceptance of risk on the line signaled to every militiaman that he was sharing their fate. Primary accounts emphasize the confusion inherent in the nighttime operation, showcasing Prescott’s leadership in mitigating disorientation.

At the third British assault, Prescott’s risk calculus paid dividends: the enemy suffered approximately 1,054 casualties, which was more than double the colonial losses, losing momentum for three critical assaults before the militia withdrew. By embracing risk to achieve surprise and terrain advantage, Prescott forced the British into a frontal attack under lethal conditions. His risk calculus underscores that seizing opportunities often requires tolerance for exposure and uncertainty. His deliberate positioning under British guns illustrated an understanding of risk-reward tradeoffs central to the conduct of operations.

Conclusion

In conclusion, COL Prescott executed the mission command principles of competence, shared understanding, disciplined initiative, and risk acceptance. His technical competence in rapid entrenchment and fire discipline established resilient defenses under naval bombardment. By articulating intent with an emphasis on terrain, he ensured shared understanding, melding a synchronized, diverse militia element into a unified lethal force. Trusting subordinate leaders to act within his intent unleashed disciplined initiative. Prescott’s deliberate acceptance of risk seized the operational initiative and inflicted disproportionate casualties on trained British troops. The preservation of Breed’s Hill as a monument underscores the battle’s symbolic importance in American heritage. The actions observed in the Battle of Bunker Hill affirm that mission command principles are a lived practice, honed under pressure and adversity.

The foundational principles Prescott demonstrated remain just as relevant for today’s complex battlefield. Future leaders who cultivate deep expertise, foster shared understanding, empower disciplined initiative, and embrace calculated risks can transform their teams into resilient, decisive forces that achieve bold objectives and inspire lasting commitment.

--------------------

CPT Juan C. Jaico Jr. is currently a student in the Logistics Captains Career Course at Army Sustainment University in Fort Lee, Virginia. He previously served as executive officer for a forward support company supporting a field artillery battalion in the 10th Mountain Division in Fort Drum, New York. He served as an operations officer in 10th Mountain Division G33 in support of Operation European Assure, Deter, and Reinforce in 2023. He is a graduate of the Basic Officer Leaders Course under the Ordnance branch. He has a Bachelor of Arts degree in psychology from City University of New York, York College.

--------------------

This article was published in the winter 2026 issue of Army Sustainment.

RELATED LINKS

The Current issue of Army Sustainment in pdf format

Current Army Sustainment Online Articles

Connect with Army Sustainment on LinkedIn

Connect with Army Sustainment on Facebook

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Social Sharing