As our final command post exercise (CPX) ended, the morale and spirit of the sustainment enterprise across the 1st Armored Division (1AD) was high. We validated our standard operating procedures, exercised our systems and processes, and developed a strong concept of support at both the division and brigade levels — or so we thought.

During the CPX III after-action review (AAR), we realized that despite all our hard work and efforts, the sustainment enterprise was not able to get beyond 48 to 72 hours in terms of sustainment planning and execution. Throughout the exercise, it felt like 1AD sustainers were in a knife fight during all phases of the operation. Despite their best efforts, sustainers kept getting dragged back into the current operations (CUOPS) fight instead of getting to the future operations plan horizon, which is where they needed to be to assure proactive versus reactive sustainment.

If the sustainers of 1AD really wanted to extend operational reach and prolong endurance, they needed to figure out a way to forecast sustainment requirements out to the 96- to 120-hour time horizon. At the start of operations, MG Curtis Taylor, commanding general (CG), 1AD, provided clear guidance for the sustainment enterprise: he said that sustainers must “anticipate requirements and echelon sustainment assets forward on the battlefield to enable the division to maintain pace and tempo without culminating.” Given the CG’s guidance, sustainers began developing a plan to get beyond 72 hours.

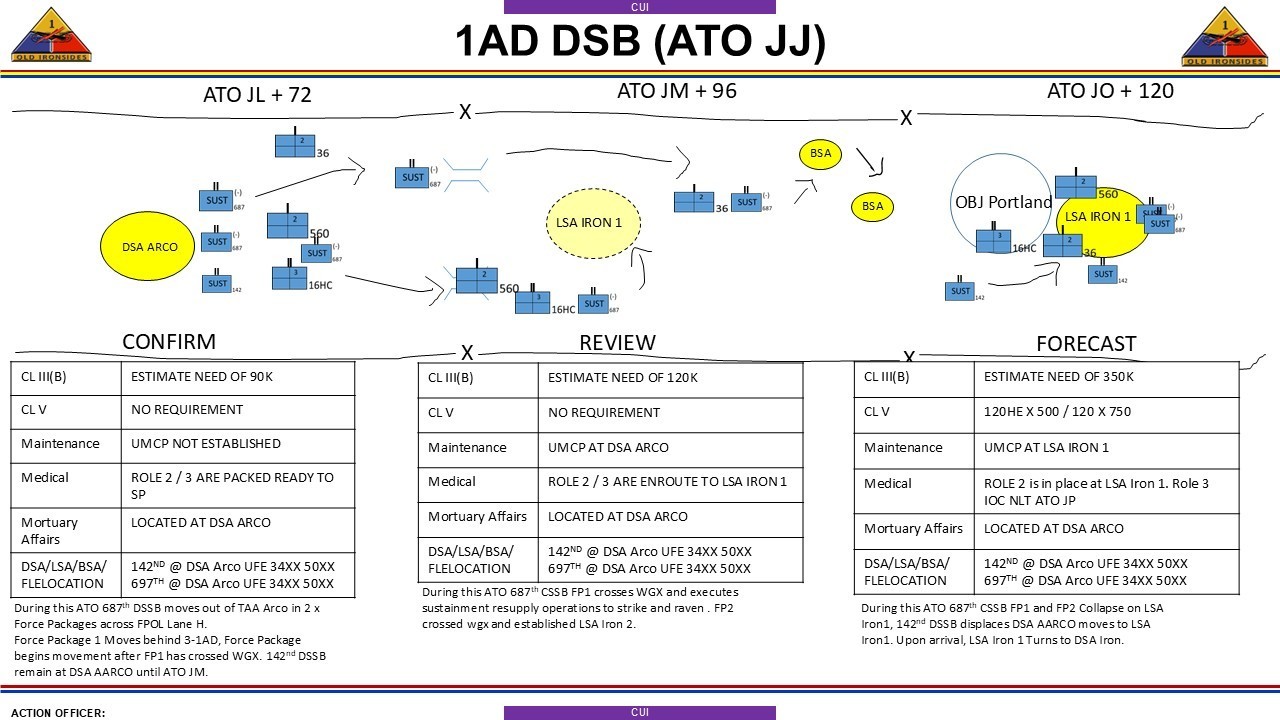

When the division arrived at Fort Leavenworth for academics before Warfighter Exercise (WFX) 25-1, it was mentored by Retired MG Kurt Ryan, who provided invaluable insights and guidance on ways to achieve our goal of planning sustainment operations 96 to 120 hours out. One of his many recommendations was to reevaluate our logistics running estimates and develop logistics limits of advance (LOAs) based on the maneuver concept and existing sustainment architecture in time and space. Doing this enabled the 1AD CG and the deputy commanding general for support (DCG-S) to see how far sustainers could sustain the operation with critical commodities before needing to echelon sustainment nodes forward. The LOA products that we developed enabled 1AD to better understand and integrate sustainment capabilities and shortfalls into the overall maneuver plan. By combining sustainment and maneuver planning efforts, we sought to reduce unforeseen requirements and eliminate friction points within the 24- to 48-hour execution timeline. From MG Ryan’s perspective, friction within the 24- to 48-hour execution timeline was the leading factor in the sustainment enterprise’s inability to get beyond the CUOPS fight. Using this guidance, we began focusing on producing LOA’s for Class III(B), Class V, Maintenance, Medical, and Mortuary Affairs.

MG Ryan and the 1AD Division Sustainment Brigade (DSB) commander, COL Delarius Tarlton, also advised us to reevaluate our sustainment critical path, verify whether we had the right people attending each meeting, and, most importantly, if we had the right inputs and outputs. The division G-4 planners and DSB support operations (SPO) began reevaluating the critical path, the inputs and outputs, and the products used in each meeting.

As expected, we determined that some battle rhythm events were duplicates of other events, except for the title. We eliminated duplicate events, changed the timing of each event, and updated the inputs and outputs. The resulting schedule was more logical and enabled us to prevent unforeseen requirements and move beyond the 48- to 72-hour time horizon. We also updated our sustainment products to make meetings more efficient. We drastically changed our logistics synchronization (LOGSYNC) and sustainment working group slide deck, which enabled units to produce the required information more quickly and encouraged collaboration among the brigades.

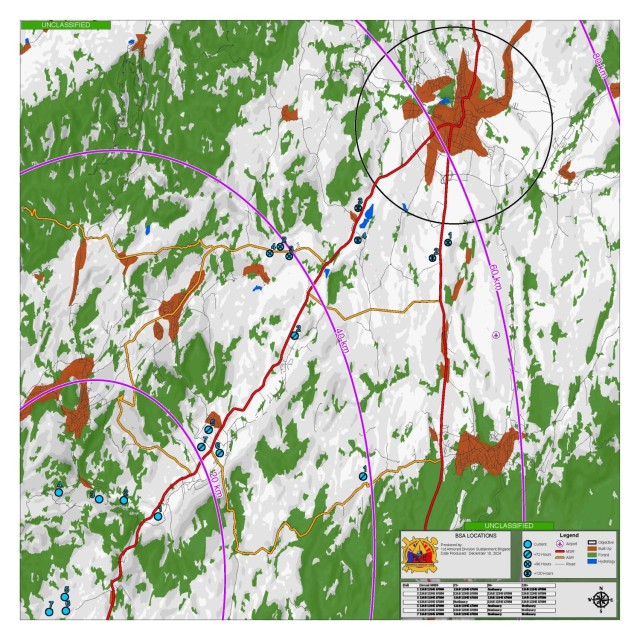

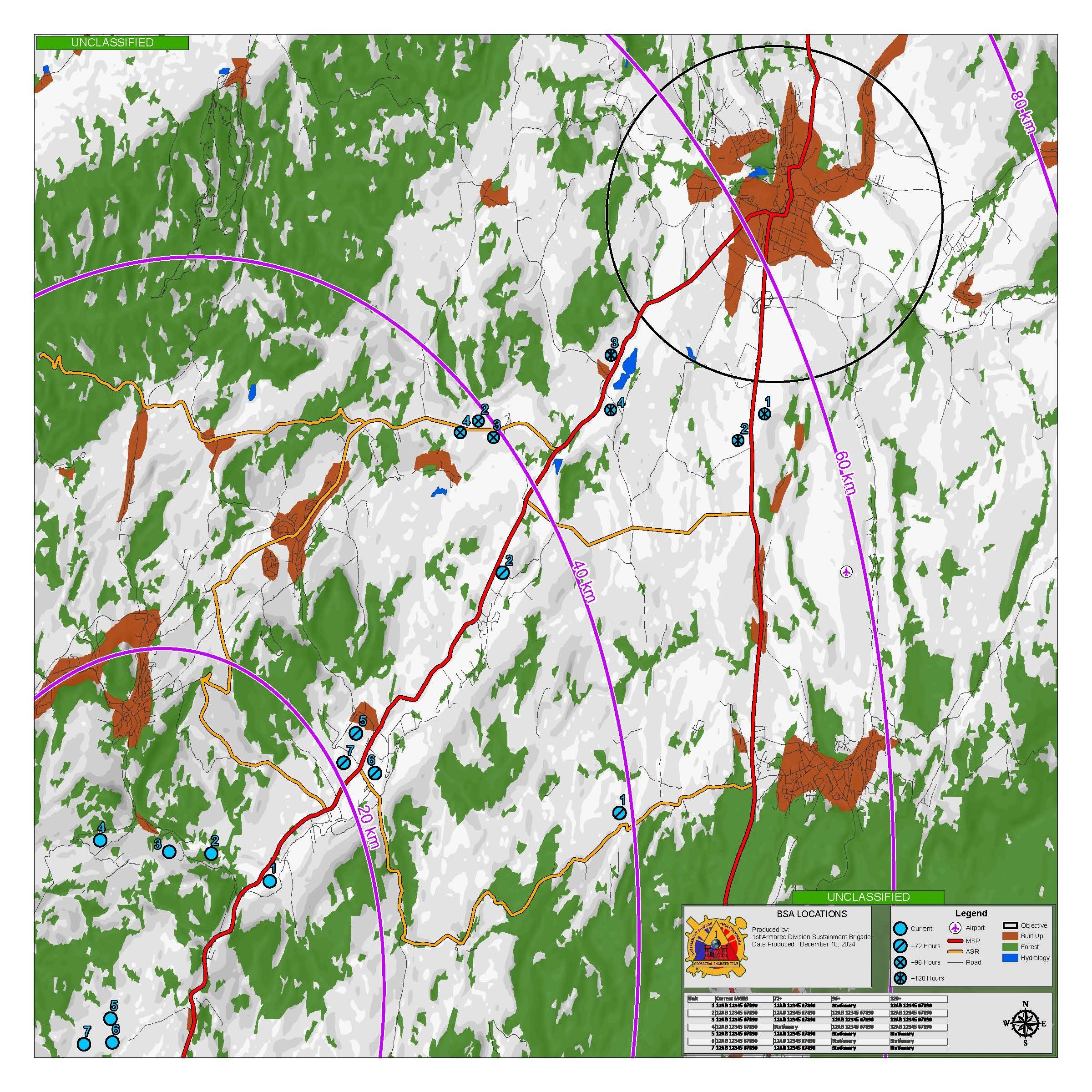

While revising fighting products and the critical path, we also leveraged other assets within the DSB to increase shared understanding of key sustainment nodes. We realized that the S-2 (intelligence) geospatial team could provide more than just route or terrain analysis. The team can identify additional main supply routes and alternate supply routes. They can also provide imagery of key terrain, detailed analysis, recommendations for division support area (DSA)/brigade support area (BSA) locations and field hospital locations.

The geospatial team also aided in the establishment of the division’s Iron Forge reconstitution site. The team worked closely with the division’s fires, protection, and G-4 maintenance sections and recommended a location that was outside enemy medium artillery range for the execution of reconstitution operations. The reconstitution site was critical to the success of the division.

After disseminating the new battle rhythm and sustainment critical path throughout the division, it was time to execute. We executed a successful sustainment rehearsal and immediately began WFX 25-1. Just like in CPX III, our DSB team started out with a sustainment synchronization matrix that included templated sustainment resupply operations out to 96 hours and planned operations out to 120 hours. By the end of day 1, the DSB started receiving unplanned and/or emergency resupply requests. These emergency resupply requests were once again keeping sustainers in the CUOPS fight and prevented us from reaching our goal of planning sustainment operations out to 96 to 120 hours. At the end of day 1, MAJ Cardenas, 1AD DSB SPO officer, gathered the team, and analyzed all emergency resupply requests. The team realized that based on sustainment running estimates, calculations, and unit logistics status reports, none of the emergency resupply requests were actual emergencies.

All brigades were above 2-plus days of supply (DOS). However, the war on terrorism mentality and experience of always operating in the green was evident. Brigades were not used to fighting in the red or with one DOS. To prevent further emergency resupply requests, we refocused all subordinate units during the LOGSYNC. The DSB and G-4 team, with oversight from BG Jared Bordwell, 1AD DCG-S, established a procedure to make the LOGSYNC quicker, more direct, and solely focused on answering one question: “Can you sustain the fight for the next 24 hours?” The DSB SPO officer developed and provided the brigades with a nine-line sustainment LOGSYNC template that captured the pertinent information needed to assess the sustainment posture of each unit and validate any unforeseen requirements before they became emergencies. As the division SPO officer, MAJ Cardenas was empowered to adjudicate what constituted an emergency.

At the midpoint AAR, sustainment operations were going well, and sustainment planning was out to 72 hours, but the division had not yet reached its goal of 96 to 120 hours. We were coached to think about whether the number of sustainment missions we were executing daily was reasonable and feasible. In the simulation, the plan seemed to work. However, in a real fight, we would have been pushing our crews to their limits. On average, we were executing 11 sustainment missions daily. Our organic division sustainment support battalion and supporting combat sustainment support battalion had the assets and capabilities to execute, but protection assets were limited, and availability became scarce as the battle went on.

As we transitioned to the second phase of WFX 25-1, we reassessed the amount of sustainment resupply missions that were necessary to maintain tempo and cut the number of daily sustainment missions from 11 to four. We incorporated the priorities of support published by the division G-4, our logistics LOAs, and included input from the brigades during our sustainment working group to determine the appropriate number of missions. During our working group, we started focusing only on sustainment operations at 72 to 96 hours and 120 hours. We used a simple course of action sketch slide, and each brigade discussed their concept of support for these timeframes. This practice enabled shared understanding across the division. Brigades were able to assist and share assets, which led to more efficient use of sustainment platforms and made maneuver plans more supportable. During the working group, we also provided brigades with a map that contained the location of key sustainment nodes, such as the DSAs/BSAs at 72 to 96 to 120 hours out. By the end of WFX 25-1, we were planning sustainment operations 120 hours out and were confident that 1AD had the appropriate systems and processes in place to continue this standard going forward.

Key Takeaways and Lessons Learned from WFX 25-1

- In large-scale combat operations (LSCO), brigades must get comfortable fighting in the red and trust that the sustainment plan is nested with the maneuver plan and any contingencies that might arise. Sustainment critical path meetings and anticipatory sustainment will ensure that planned and scheduled resupply operations are already in the pipeline and will arrive before the unit needs them.

- Division rear command post (RCP) and DSB command post must be nested and share the same common operational picture. The DCG-S and DSB commander must strictly enforce the sustainment critical path and must ensure that the appropriate attendees are present and that each meeting includes inputs and outputs that enable the sustainment enterprise to see the battlefield and potential friction points 96 to 120 hours out. The sustainment critical path must be continuously reassessed and updated when necessary to afford sustainers the maximum flexibility to sustain the division.

- In LSCO, it is imperative that collaboration and coordination with higher and adjacent units is the norm. Divisions and brigades must be in constant coordination and communication with adjacent units and exploit windows of opportunity gained by the actions of another unit. There is nothing wrong with divisions working with adjacent divisions to solve a similar problem. Parallel planning is critical.

- Sustainers must be creative and maximize internal/external assets to enable sustainment operations. DSBs must leverage corps and expeditionary sustainment command (ESC) assets to assist the division with executing the sustainment plan. The ESC is a critical enabler and can also be used to establish and operate key sustainment nodes and logistics supply areas for a specific battle period in support of the division. Partnering with the ESC enables DSBs to echelon sustainment as far forward as possible to extend the operational reach of the division.

- Divisions must leverage the ESC and request that the ESC provide throughput to forward BSAs when possible. These actions must be rehearsed and included in the sustainment plan. Doing this allows the DSB to manage critical and finite resources while increasing sustainment velocity. Key times for the ESC to provide throughput to BSAs are when the DSA is preparing to displace and while the DSA is moving. The ESC can also enable divisions to achieve tempo at the start of operations before forward passage of lines by prepositioning critical fuel, maintenance, medical, and distribution assets in the division tactical assembly area, enabling DSB assets to remain packed and ready to move.

- Maintaining combat power across 1AD was challenging given the amount of combat losses, limited availability of critical Class IX repair parts, and Class VII end items. To overcome this challenge, the DSB’s material readiness branch, the division G-4 section, and the field support battalion’s division logistics support element partnered up and established the division’s reconstitution site where battle damaged equipment was retrograded for repair. In coordination with the 13th Armored Corps Sustainment Command (ACSC) and III Armored Corps G-1, personnel replacements, Class VII end items, and critical Class IX parts were delivered via throughput to execute reconstitution operations. Iron Forge was the name given to this reconstitution operation. Iron Forge later became the name used to identify the process for reconstitution efforts across the division, which included retrograding all battle losses and battle-damaged equipment from the brigades to a single location in the rear area. Iron Forge was now an entity that existed solely to manufacture combat power incrementally and in sub-units. In less than 48 hours, the 1AD Cavalry Squadron went from 20% combat power to more than 65% combat power and returned to complete its new mission. Iron Forge was successful, and the division staff realized it could generate considerable results if adequately resourced. Iron Forge not only remained operational, but it also became a requirement.

During LSCO, combat losses will often exceed the capability of the supply system to get personnel and equipment into the fight. In WFX 25-1, III Armored Corps had to prioritize limited Class VII and personnel replacements among two divisions, which resulted in very limited Class VII replacements or in a long time frame in which Class VII replacements were arriving to 1AD. Iron Forge provided a necessary capability that enabled the division to overcome this challenge by allocating personnel and resources to receive personnel and equipment replacements, repair broken equipment, and conduct training to ensure a qualified crew moved forward with equipment as it was returned to the fight. Divisions must develop an Iron Forge-like capability to overcome the demands that LSCO places on the supply system. - Units must maximize training and learning opportunities for Soldiers, NCOs, and junior officers. Staff NCOs and officers must be encouraged to provide their insights, analysis, and recommendations. Doing so will ensure that junior leaders are confident and know that their input is critical to the success of the operation.

Conclusion

1AD was very successful during WFX 25-1 due to the hard work and dedication of the entire sustainment enterprise. Sustainment professionals from across the division took the lessons learned from all the training events leading up to the WFX and improved with each iteration. The amount of improvement shown by the members of the 1AD Sustainment Brigade and the 1AD RCP was nothing short of stellar. From figuring out the RCP layout/DSB division materiel readiness center integration and updating the sustainment critical path and RCP fighting products, everyone maintained a professional and positive attitude, enabling an open collaborative working environment.

Through a combination of advanced data analytics, refined forecasting models, and enhanced communication with adjacent divisions and the 13th ACSC, 1AD successfully achieved its sustainment planning goal of forecasting sustainment support 96 to 120 hours out. This achievement significantly improved mission readiness, reduced logistical bottlenecks, and ensured the continuous flow of critical commodities during a dynamic and challenging WFX against a very capable opposing force.

--------------------

COL Delarius Tarlton serves as the commander of the 1st Armored Division, Division Sustainment Brigade, at Fort Bliss, Texas. He recently served as the chief of sustainment of the 1st Cavalry Division at Fort Hood, Texas. He previously served as the commander of the 15th Brigade Support Battalion, 2nd Armored Brigade Combat Team, 1st Cavalry Division, at Fort Hood. He was commissioned as a lieutenant of Air Defense Artillery through the Army ROTC Program at Florida A&M University. He later received a branch transfer into the Quartermaster Corps. He has a Master of Science degree in business with a concentration in supply chain management and logistics from the University of Kansas, and a Master of Strategic Studies from the U.S. Army War College.

MAJ Jerrie Cardenas serves as the support operations officer for the 1st Armored Division Sustainment Brigade, 1st Armored Division. He previously served as the lead integrator for sustainment experimentation at the Joint Modernization Command, S-4 for the 36th Engineer Brigade, and commander of Echo Forward Support Company, 123rd Brigade Support Battalion, 3rd Bulldog Brigade, 1st Armored Division. He was commissioned as a lieutenant in the Ordnance Corps. He has a Master of Business Administration degree with a concentration in management from Texas A&M International University.

--------------------

This article was published in conjunction with the fall 2025 issue of Army Sustainment.

RELATED LINKS

The Current issue of Army Sustainment in pdf format

Current Army Sustainment Online Articles

Connect with Army Sustainment on LinkedIn

Connect with Army Sustainment on Facebook

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Social Sharing