This article is part of a series that will delve into the history of the Trinity Site Test, which marked its 80th anniversary on July 16, 2025, and the commemoration of the growth and evolution of White Sands Missile Range, which marked its 80th anniversary on July 9, 2025. A commemoration of the establishment of White Sands Proving Ground, now called White Sands Missile Range, will take place on Oct. 17 at WSMR and an observance for the test at Trinity Site will take place on Oct. 18 at the Trinity Site Open House.

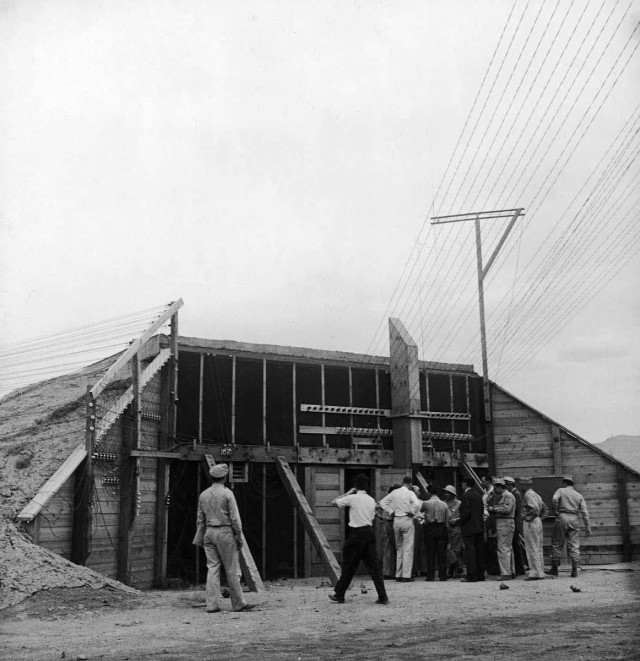

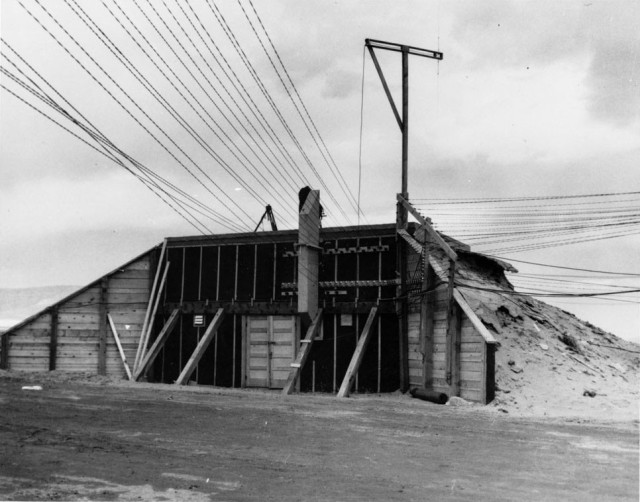

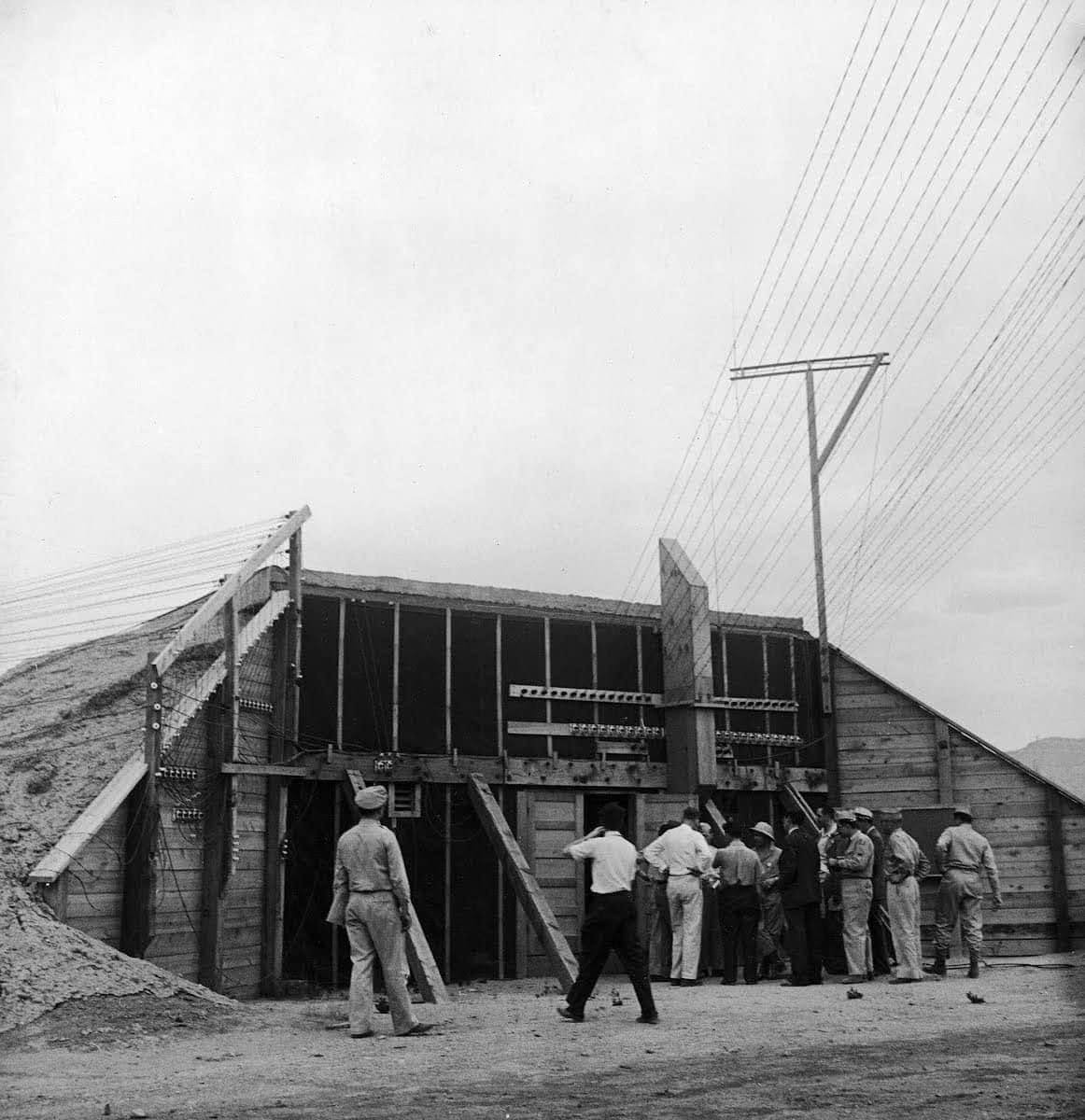

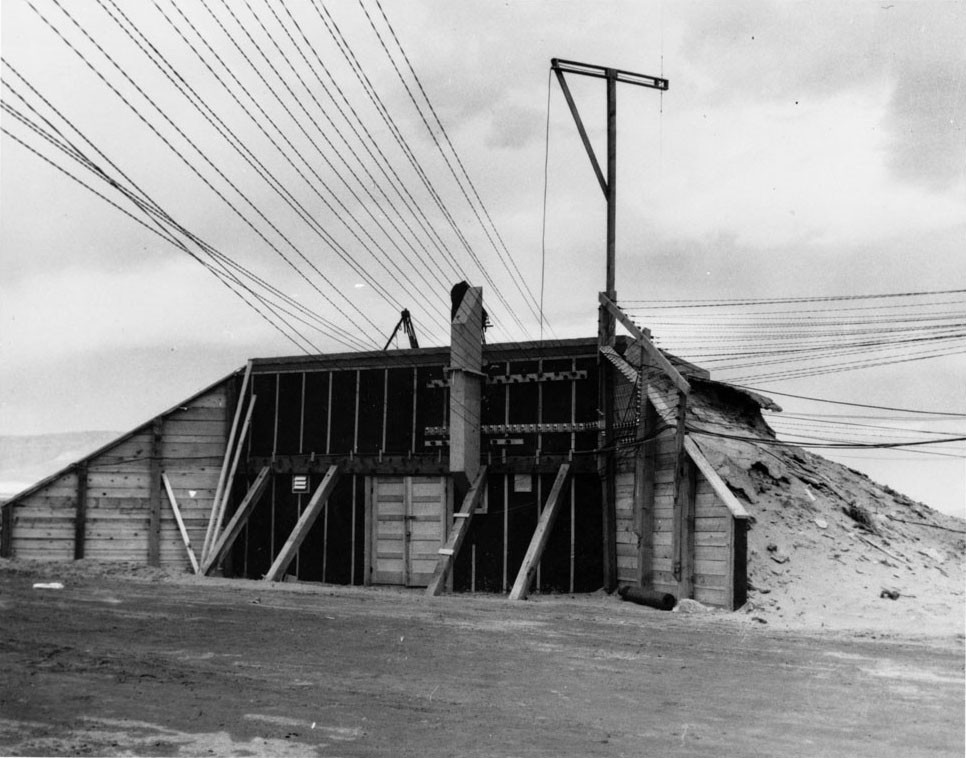

In preparation for the test, three observation points were established at 10,000 yards from ground zero to the south, north and west, and each had a direct line-of-sight to ground zero. These bunkers were known as South 10k, North 10k and West 10k. These were concrete shelters protected by wood structures and earthen berms. These three bunkers were the closest manned positions to ground zero during the test.

South 10k was the control center for all test activities and where the device was triggered. Due to deterioration, the Army dismantled South 10k in 1965, leaving only a concrete slab to mark this historic location. The concrete bunkers at North 10k and West 10k remain but the supporting wood structures and earthen berms were removed.

The test leadership were at different locations during the test: Dr. J. Robert Oppenheimer, head of Los Alamos National Lab, was at South 10k and controlled the execution of the test; while the Director of the Manhattan Project, Maj. Gen. Leslie Groves, observed the test from base camp, ten miles southwest of ground zero and four miles from South 10K; and Dr. Edwar Teller, a leading project scientist, watched from Compania Hill, 20 miles northwest of ground zero.

According to Jim Eckles in his book “Trinity,” a few small instrumentation bunkers were also constructed closer to ground zero. One of those bunkers, which can be seen when driving into the site, is only 800 yards from ground zero. That bunker was originally built to protect Fastax cameras. These bunkers are small and were only built to protect test equipment.

According to Berlyn Brixner, Los Alamos photographer, he had to change plans for some of these cameras. Tests determined that cameras close to ground zero, like the ones at the west 800-yard bunker, would be exposed to high levels of radiation and the film would never survive. Before the test, the cameras were moved to a sled outside the bunker. Brixner and his team fabricated lead boxes to protect the cameras. The boxes were mounted on the sled that was placed at the 800-yard bunkers. The cameras were pointed straight up through windows made of leaded glass. Mirrors were positioned over the cameras and angled so each camera was focused on the tower. These “periscopes” protected the cameras from the direct effects of the test.

After the test, the crews used the thousand-foot cable attached to the sled to pull it back to their position. This eliminated any unnecessary exposure to the high levels of radiation in the immediate ground zero area right after the explosion.

Eckles goes on to write that on the night of the test, personnel stationed at various bunkers didn’t receive much information about the rain delay from 4:00 a.m. to 5:30 a.m. for the detonation. On one of his visits to Trinity Site, Brixner told Eckles he knew there was a delay at 4 a.m. but had no idea of the new test time. Brixner was on top of the North 10k (he was one of the few people allowed to watch the test from outside a bunker) as he operated a 35mm Mitchell motion picture camera mounted on a machine gun turret that allowed him to track the fireball and cloud. The camera was equipped with a 75mm lens and was running at 24 frames per second.

According to Eckles, Brixner said he was never told the new detonation time, but some seconds before the blast his camera powered up, so he knew it was time to go to work (the camera was switched on by the automatic sequencing system located in the South 10k). Then the switch was thrown to start the process, cameras and other instruments sprang to life, flares were ignited, and the device was triggered at a precise moment in the sequence, and history was made in the New Mexico desert.

Social Sharing