(Image courtesy of the National Guard Bureau) VIEW ORIGINAL

While many historians have written about the tactics and strategy employed during the 1863 Battle of Gettysburg, they generally overlook the mental and physical demands of the Soldier. For the Army of the Potomac, the battle began as a foot race to secure advantageous ground and ended as a desperate fight to retain that ground. The victory at Gettysburg was not only a result of tactics and strategy, but it was also a triumph of the individual Soldier’s toughness. Their toughness had an impact before, during, and after the fight. Understanding this critical factor can further military leaders’ appreciation of decisions and tactics. Military professionals would do well to understand this well-known but rarely discussed factor of the Union victory.

Toughness Defined

Toughness involves physical, mental, and spiritual components. Current U.S. Army doctrine does not singularly define toughness. “Resilience” comes close. The Army defines resilience as “demonstrating the psychological and physical capacity to overcome failures, setbacks, and hardship.”[1] The U.S. Navy more directly defines toughness in three ways: “1) the ability to take a hit and keep going, 2) perform under pressure, and 3) excel in the day-in and day-out grind.”[2] The Army’s “resilience” and the Navy’s “toughness” are similar; however, neither adequately addresses the character of infantry combat at Gettysburg. A definition of toughness that describes what Soldiers in the Army of the Potomac had to endure is required. Accordingly, toughness, in this sense, is moving dozens of miles, fast, on foot with little food or sleep, and upon arriving at the battlefield, being prepared to engage in vicious close combat. Their actions were all conducted without the benefit of modern equipment and medicine. Simply put, these men were tough. Nowhere was this more evident than in the troop movements to the fight.

(Graphic courtesy of the Library of Congress) VIEW ORIGINAL

Tremendous Marches

In the days preceding the battle, the Army of the Potomac marched hard to give Major General George Meade tactical flexibility. “Our new commander is determined not to let the grass grow beneath our feet,” stated one officer.[3] Starting on 29 June, the left wing of the Union Army marched more than 30 miles to reach Emmitsburg, MD, some 5 miles from Gettysburg.[4] One Soldier described these movements as “tremendous marches.”[5] On 1 July, after hearing reports that a general engagement was occurring at Gettysburg, the First and Eleventh Corps commanders, Major General John Reynolds and Major General Oliver O. Howard, made haste toward the front. Upon arrival, they ascertained that whoever could marshal troops more quickly and efficiently would have the advantage in the coming fight.[6] With no major railroads to utilize, Soldiers of the Army of the Potomac would now have to move quickly over dozens of miles through the rough terrain of Maryland and southern Pennsylvania. Consequently, the battle’s outcome now depended on the physical toughness of individual Soldiers enduring forced marches in the summer heat.

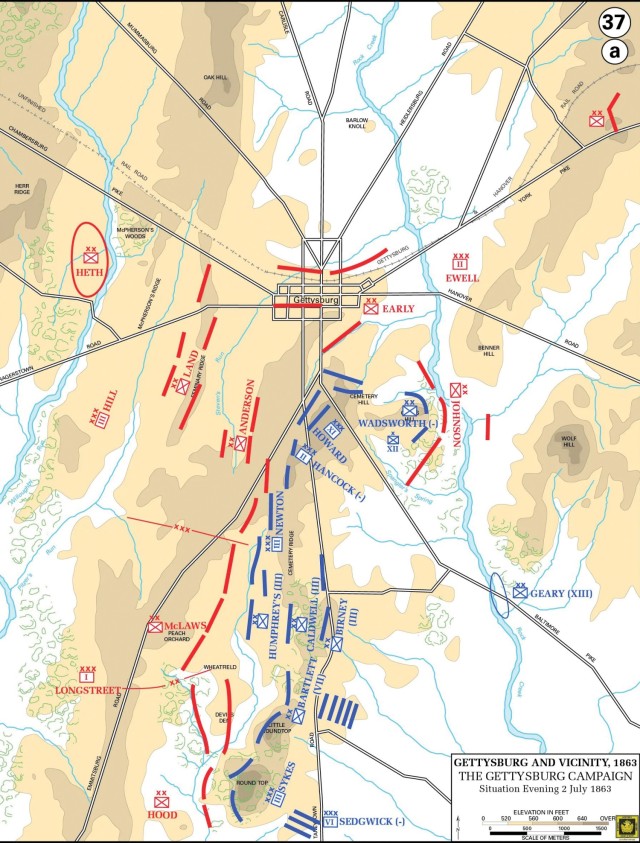

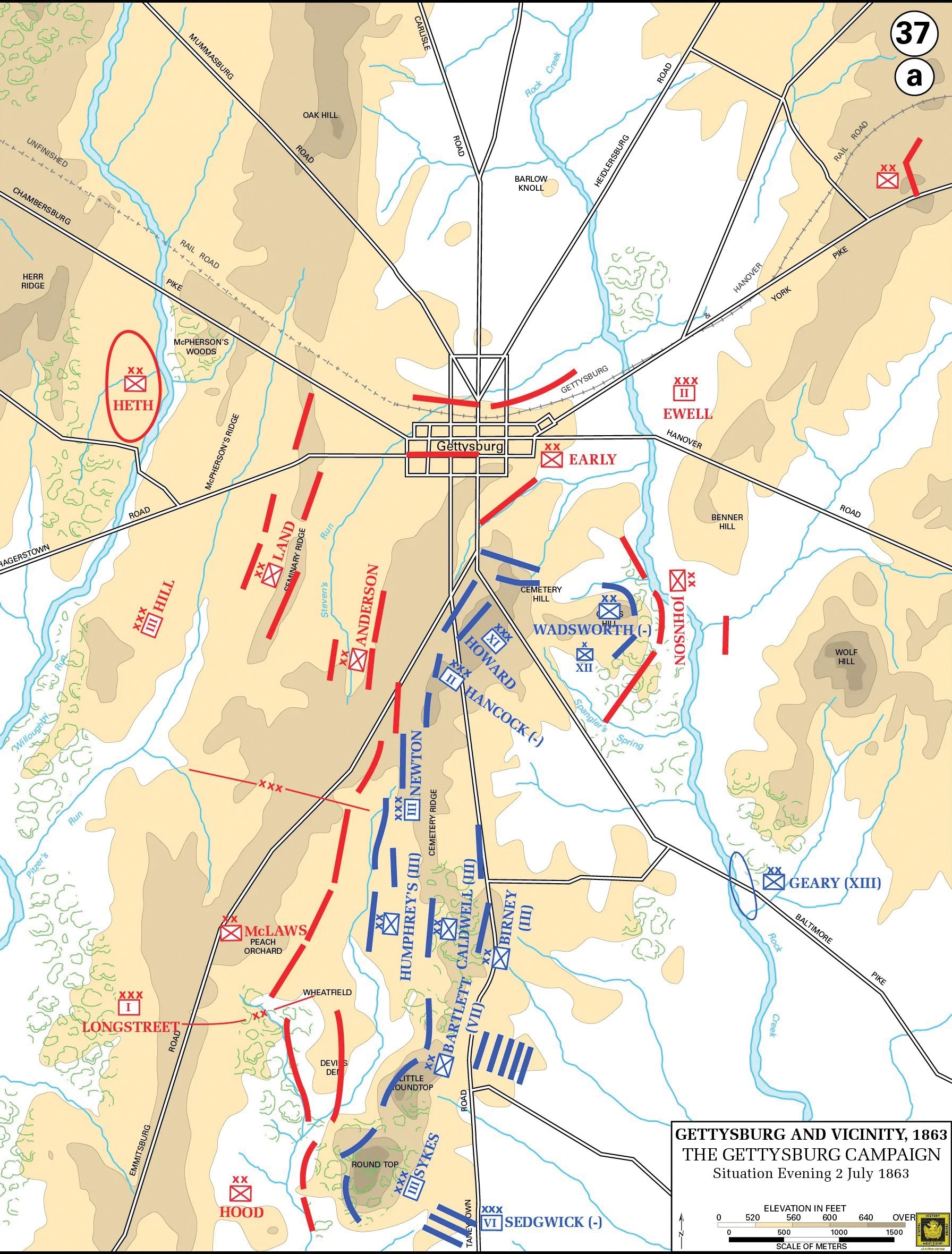

The left wing of the Union Army held the Confederates for most of the day on 1 July, but Meade’s decision to commit the remainder of the Army to Gettysburg came later that evening. As a result, massing forces quickly became imperative for the Union. The Third Corps was close, but the remainder of the Army was further away. The Fifth Corps marched 23 miles on 30 June and stopped at Hanover, PA. At around 1800 on the 1st, they began a forced march of about 12 miles to Gettysburg, where they arrived the following day.[7] By noon on 2 July, most of the Army of the Potomac had arrived at Gettysburg except for the Sixth Corps.[8] The Sixth Corps, the most robust corps in terms of numbers for the Army, began 1 July some 35 miles from Gettysburg.[9] It was imperative that they arrive to influence the battle’s outcome. Accordingly, Major General John Sedgwick put his Soldiers on the road. For the next 19 hours, the Sixth Corps marched 35 miles in the hot July sun and reached the battlefield around 1700 on the 2nd.[10] By that evening, the Army of the Potomac had successfully massed enough combat power to counter the Confederate assault. If the Army had not been able to mass quickly on 1 and 2 July, the Confederate Army could have rapidly taken the commanding terrain surrounding the town. The Federals’ ability to mass was due to the toughness of Soldiers.

It is essential to understand these marches in the context of the equipment of the time. Compared with today’s Army, a Soldier’s kit during this period was primitive and not designed for maximum comfort. There were no Danner boots, Jet Boil stoves, or Camelbaks. Union Soldiers wore wool uniforms and carried blankets and bivouac kits, even in the summer. Kits would weigh around 50 pounds with weapons, ammunition, and everything they needed for a march.[11] There were no carbo-loaded Meals, Ready-to-Eat (MREs). Soldiers on the march ate hard tack, foraged for food, and occasionally had a hot meal. The “Brogan” was the typical footwear issued to Union Soldiers. These were crudely designed and made left and right by breaking them in on the march.[12] If you were a Confederate Soldier, matters were even worse, as many marched barefoot due to supply shortages. In short, marching to Gettysburg with this equipment took a physical toll on the body, and these men had to fight immediately upon arrival. The summer heat made conditions more miserable.

The hot, humid weather around Gettysburg exacerbated Soldiers’ discomfort. Temperatures hovered around the 80s, with a high of 87 degrees Fahrenheit on the final day of the battle.[13] As a result, water was imperative for Soldiers to continue fighting. But collecting drinking water was no easy task. Union Soldiers typically carried one canteen and filled water from streams or springs. Heat stroke became a factor. There were an estimated 7,000 cases of heat stroke during the Civil War.[14] Additionally, the dust created by long lines of marching Soldiers created another discomfort.[15] As one Soldier described it: “To see men fall from exhaustion, clothes wet, faces and teeth black with dust, lips parched, eyes sunken, feet blistered, then driven on at the point of the bayonet.”[16] Despite the heat, dust, and limited water, the Army of the Potomac pressed on to the fight. Their physical toughness gave the Union a decisive edge, but merely getting to the fight did not secure victory.

(Photo courtesy of the Library of Congress) VIEW ORIGINAL

Close Combat

After all-night marches with little rest, Soldiers had to summon the mental toughness and fortitude to fight the enemy in close quarters using 19th-century tactics. During that period, discipline was paramount, and with good reason. In 1863, the maximum effective range of a rifle with the new Minnie ball ammunition was around 400 yards, with a rate of fire of about three shots per minute.[17] While the Minnie ball had a better range than earlier ordnance, Soldiers still marched shoulder to shoulder within shooting range of their enemy to concentrate fire. A Soldier breaking ranks could disrupt the line and lead to chaos. As a result, Soldiers generally used Napoleonic tactics with more modern weapons. Naturally, this led to more casualties. In today’s Army, a medical evacuation within 60 minutes (the Golden Hour) of serious injury is the standard, but in 1863, there was no such thing. Medicine was still crude, and amputation was the accepted practice. To keep order, officers and NCOs used swords, revolvers, bayonets, or the threat of firing squads to enforce compliance. Consequently, even after pushing themselves beyond their physical capacities, these Soldiers had to face the hell of fighting a determined enemy using crude tactics. Adding to the ferocity of the fight were the motivations of each side.

Each army had a deep sense of purpose leading up to the battle. According to modern U.S. Army doctrine, “purpose” is the reason for Soldiers to achieve desired outcomes.[18] Confederate forces entered Pennsylvania confident of their fighting abilities. The Confederate Army was motivated to take the war to their enemy’s home territory and inflict the suffering they had felt in previous years. The Army of the Potomac was determined to defend its home territory and wanted to avenge recent losses. Additionally, each side sensed that the next fight would be decisive. As a result, fighting took on a more intense and personal character.

The combination of the weapons, tactics, physical conditions, and motivations made infantry fighting at Gettysburg a brutal and visceral experience. Hand-to-hand combat, urban sniping, multiple bayonet charges, and the largest artillery barrage of the war highlight the ferocity of this battle. Some of the most intense small-unit actions in American history occurred at Gettysburg including Chamberlain’s defense of Little Round Top, the Wheatfield, Devil’s Den, the First Minnesota charge, and finally the defense of “The Angle” which repulsed the famous Pickett’s Charge on the final day of the battle. The Army of the Potomac could not have carried the day if it’s Soldiers had not possessed the toughness required to secure the victory under the aforementioned conditions. Indeed, their determination and sacrifice must be noted as a decisive factor in the battle’s outcome.

Modern Applications

For the Infantry, Gettysburg is a reminder that toughness matters. Tactics, strategy, and leadership are useless unless Soldiers can endure the demands of combat. Merely being in shape is not enough. Infantry Soldiers must be able to tolerate conditions that routinely push or exceed their physical and mental limitations. These men marched distances we now use for special operations selection courses with little rest and nutrition. Gettysburg demonstrates that routinely living and working on limited food and sleep is the norm and not the exception. The Russo-Ukrainian War provides a modern example. In a sensor-saturated environment, dispersion tactics increase the demands on the fitness levels of individual Soldiers, creating operating conditions reminiscent of World War I.[19] Accordingly, U.S. Army infantry leaders should focus their training programs on the reality of operating under the toughest conditions. This takes demanding, combat-focused leadership at all echelons.

Additionally, Gettysburg’s physical and mental demands remind us that, sometimes, a military leader must push his people beyond their physical and mental limits to achieve the mission. At Gettysburg, Meade did not vigorously pursue Lee immediately after the battle, which, to President Lincoln, prolonged the conflict. A number of historians agree with Lincoln’s assessment. However, this kind of decision is easier said than executed. At Gettysburg, Meade knew his Army and understood that pressing his forces further meant more sacrifice and could potentially expose his army to attack.[20] No one can blame Meade for having these concerns. However, military leaders must know when to keep pushing despite the objections of staff or subordinates. The art of leadership is understanding the capabilities of one’s organization and judiciously applying them. Accordingly, leaders must be able to steward the mission, even in the face of physical and mental exhaustion.

(Map courtesy of the U.S. Military Academy’s Department of History) VIEW ORIGINAL

Conclusion

Soldiers in the Army of the Potomac pushed beyond their limitations and won the war’s most decisive battle. Arguably, their raw toughness preserved the Union. From a historical perspective, toughness, as described above, is not unique in war, but at Gettysburg it resulted in a strategic outcome. It is a compelling illustration of why the Infantry must train and build Soldiers who can endure in the most challenging circumstances. The Army of the Potomac marched hard leading up to the fight, quickly secured the key terrain, and fought off repeated attempts by the enemy to dislodge them. Only mentally and physically tough Soldiers, fortified with a strong ethos, could withstand such conditions and carry the day. As Meade put it in his General Order on 4 July 1863: “The privations and fatigue the army has endured, and the heroic courage and gallantry it has displayed, will be matters of history, to be ever remembered.” Despite the changing character of war, the nature of combat will remain human, and human fighting involves the Infantry. Thus, future studies by military leaders must discuss how physical and mental toughness impacted Gettysburg’s outcome and influenced Meade’s decisions. Even after these Soldiers gave all they physically could, they gave some more. To prepare Soldiers for future conflict, the U.S. Army should look to the toughness of the Army of the Potomac at Gettysburg for inspiration.

Notes

1 Army Doctrine Publication (ADP) 6-22, Army Leadership and the Profession, August 2019, 51, https://armypubs.army.mil/epubs/DR_pubs/DR_a/ARN18529-ADP_6-22-000-WEB-1.pdf.

2 Navy Education and Training Command, “Warrior Toughness Terms,” https://www.netc.navy.mil/Warrior-Toughness/Warrior-Toughness-Terms/.

3 Stephen W. Sears, Gettysburg (New York: Houghton-Mifflin, 2003), 131.

4 Ibid., 144.

5 Ibid.

6 Ibid., 158.

7 Ibid., 246.

8 Ibid., 247.

9 Ibid., 240.

10 Ibid., 248.

11 “Answering the Call: The Personal Equipment of a Civil War Soldier,” Army Heritage Center Foundation (blog), n.d., https://www.armyheritage.org/soldier-stories-information/answering-the-call-the-personal-equipment-of-a-civil-war-soldier/.

12 Sarah Kay Bierle, “On the March: A Few Notes on Shoes and Boots,” Emerging Civil War (blog), 7 April 2022, https://emergingcivilwar.com/2022/04/07/on-the-march-a-few-notes-on-shoes-boots/.

13 Sue Boardman and Elle Lamboy, “An Historic Weather Report,” Celebrate Gettysburg (blog), 23 August 2017, https://celebrategettysburg.com/curb-appeal-copy/.

14 Tracey McIntire, “‘Suffocating at Each Step — Sunstroke in the Civil War,” National Museum of Civil War Medicine (blog), 19 June 2023, https://www.civilwarmed.org/sunstroke-in-the-civil-war/.

15 Ibid.

16 Sears, Gettysburg, 145.

17 Mark Grimsley and Brooks D. Simpson, Gettysburg: A Battlefield Guide (Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press, 1999), 192.

18 ADP 6-22, 26.

19 Charles McEnany and COL (Retired) Charles Roper, “The Russo-Ukrainian War: Protracted Warfare Implications for the U.S. Army,” Association of the United States Army, 1 October 2024, https://www.ausa.org/publications/russo-ukrainian-war-protracted-warfare-implications-us-army.

20 Kent Masterton Brown, Meade at Gettysburg: A Study in Command (Chapel Hill, NC: The University of North Carolina, 2021), 326.

LTC David Chichetti is an Infantry officer with more than 20 years of experience. He has a Master of Science in National Security Strategy from the National War College and a Master of Arts in Security Studies from Kansas State University. He previously commanded 2nd Battalion, 14th Infantry Regiment, which fought at Gettysburg near Houck’s Ridge on 2 July 1863.

This article appears in the Winter 2025 issue of Infantry. Read more articles from the professional bulletin of the U.S. Army Infantry at https://www.benning.army.mil/Infantry/Magazine/ or https://www.lineofdeparture.army.mil/Journals/Infantry/.

As with all Infantry articles, the views herein are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the Department of Defense or any element of it.

Social Sharing