Imagine you’re a second lieutenant (2LT) in an armored brigade combat team (ABCT) and you’ve just been placed in charge of your first platoon. You’re now responsible for not only a few dozen Soldiers, but also a platoon’s vehicles and ancillary equipment. How does a leader ensure these vehicles and supporting equipment function as designed? The broad answer is an effective maintenance program. At a minimum, maintenance must be managed at the platoon level. All platoon leaders should prioritize maintenance, as platoons train most effectively when their equipment is fully operational. Platoon leaders should become experts on their equipment status report (ESR), maintain effective platoon maintenance standard operating procedures (SOPs), and know how to conduct maintenance in all environments.

When I reported as a new mechanized infantry platoon leader in the 1st Battalion, 8th Cavalry Regiment (1-8 CAV), I encountered challenges related to maintenance operations and equipment readiness. After two years with 1-8 CAV, including my current role as the battalion maintenance officer (BMO), I have learned more about maintenance than I ever thought possible. Much of the knowledge I now possess would have helped me immensely as a platoon leader, for I would’ve been more effective at building combat power and maintaining readiness.

I once thought maintenance was an impossible task for a platoon leader to master, but it is now clear that the opposite is true. While it may seem overwhelming at first, all it takes is a bit of self-study and dedication. A platoon leader who cares about maintenance is demonstrating care for their Soldiers and for the success and lethality of their platoon.

A common misconception is that maintenance pertains only to Armor or Stryker formations, but it matters to all platoon leaders. Every platoon owns some form of equipment, which must function properly for the platoon to operate effectively. Properly functioning equipment keeps soldiers alive and helps them accomplish their mission. Another common misconception is that the company executive officer (XO) handles the entire company’s maintenance in conjunction with the company’s field maintenance team (FMT). This could not be further from the truth. While the company XO may be the steward of the company’s maintenance program, platoon leaders play a critical role. A platoon leader is responsible for the success or failure of the platoon, and that includes maintenance. A platoon cannot train or fight effectively if its equipment isn’t working properly. There is no point in planning training if the entire event is spent recovering and repairing equipment. A unit’s operational readiness must peak at the line of departure.(1)

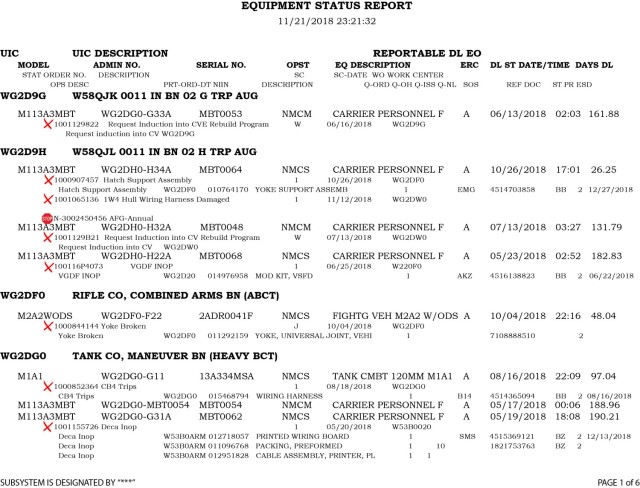

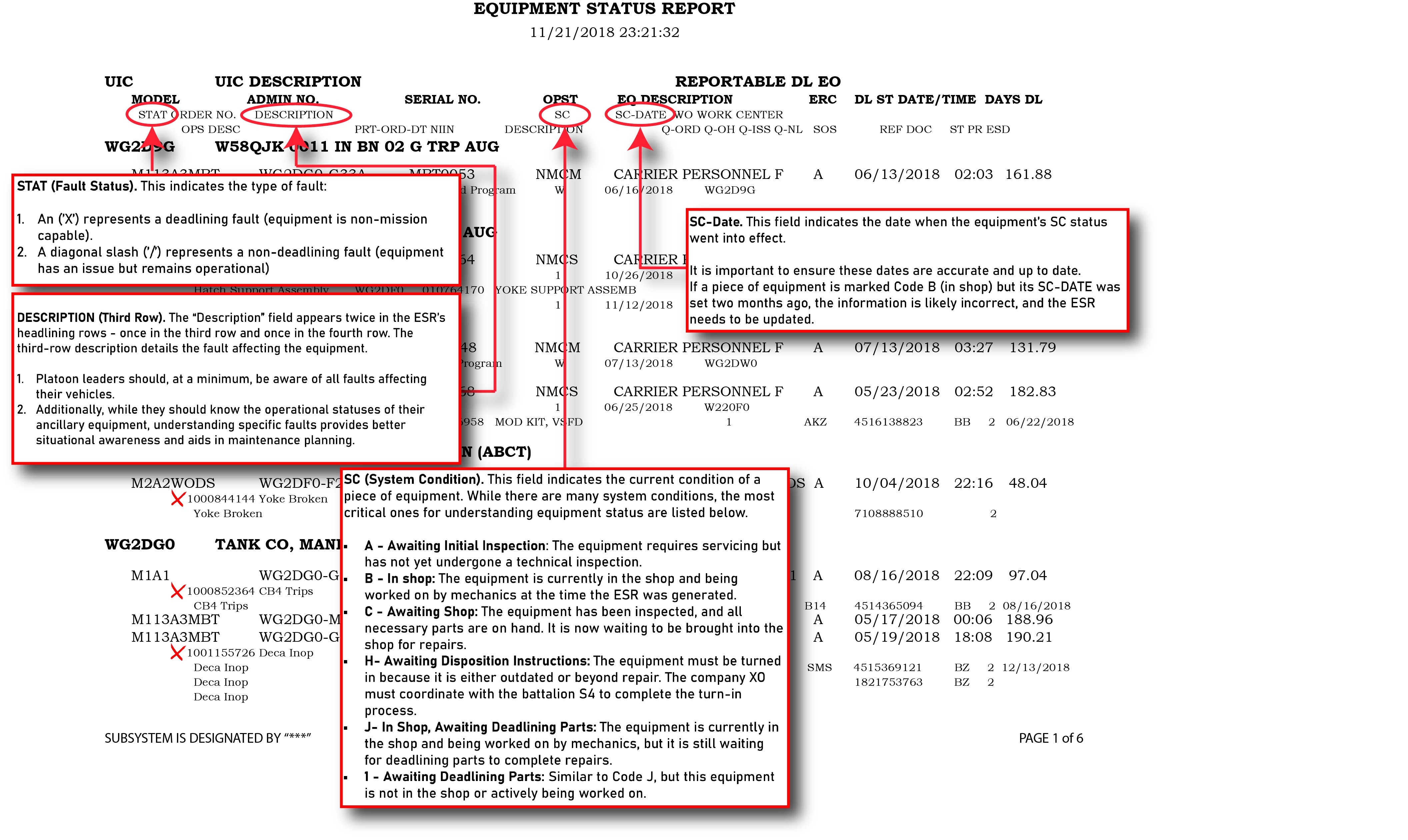

Figure 1. An example ESR page recreated from the GCSS-Army's End User Manual+ (EUM+). Of note, this ESR contains no live data and uses generic unit representations. (U.S. Army Graphic)

How to Read an ESR

The first thing a platoon leader must understand is their ESR. The ESR, accessible through the Global Combat Support System – Army (GCSS-Army), provides detailed insights into equipment and unit readiness. While the company commander and XO typically have access, a platoon leader can obtain viewing access by coordinating with their battalion’s maintenance team and following the necessary procedures.(2)

The first time looking at an ESR can be daunting—it may feel like a foreign language that platoon leaders are expected to understand immediately. However, once the headings on the ESR are understood and their corresponding information is recognized, reading it becomes much easier. The purpose of the ESR is to provide a clear picture of the status of a unit’s equipment. If there is an issue with a piece of equipment, it must be reflected on the ESR. Additionally, a fault must be listed on the ESR to order a part for it. The ESR serves as an essential system of record, enabling a platoon leader to hold themselves and their battalion’s maintenance enterprise accountable.

Each ESR page features four headlining rows at the top, distinguished by progressively smaller font sizes in descending order, as seen in Figure 1.

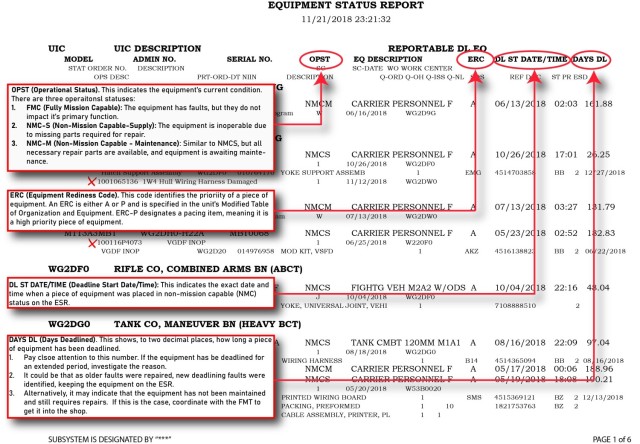

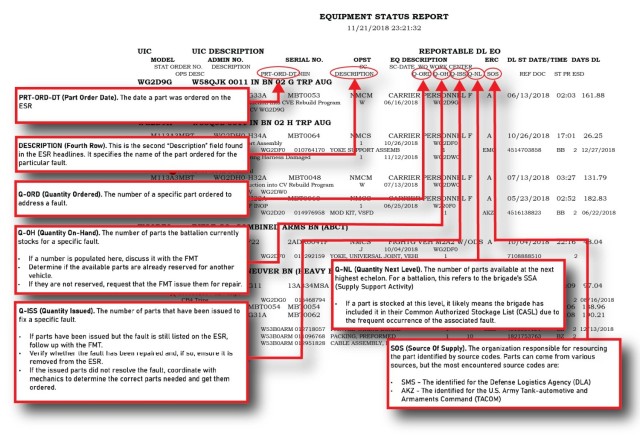

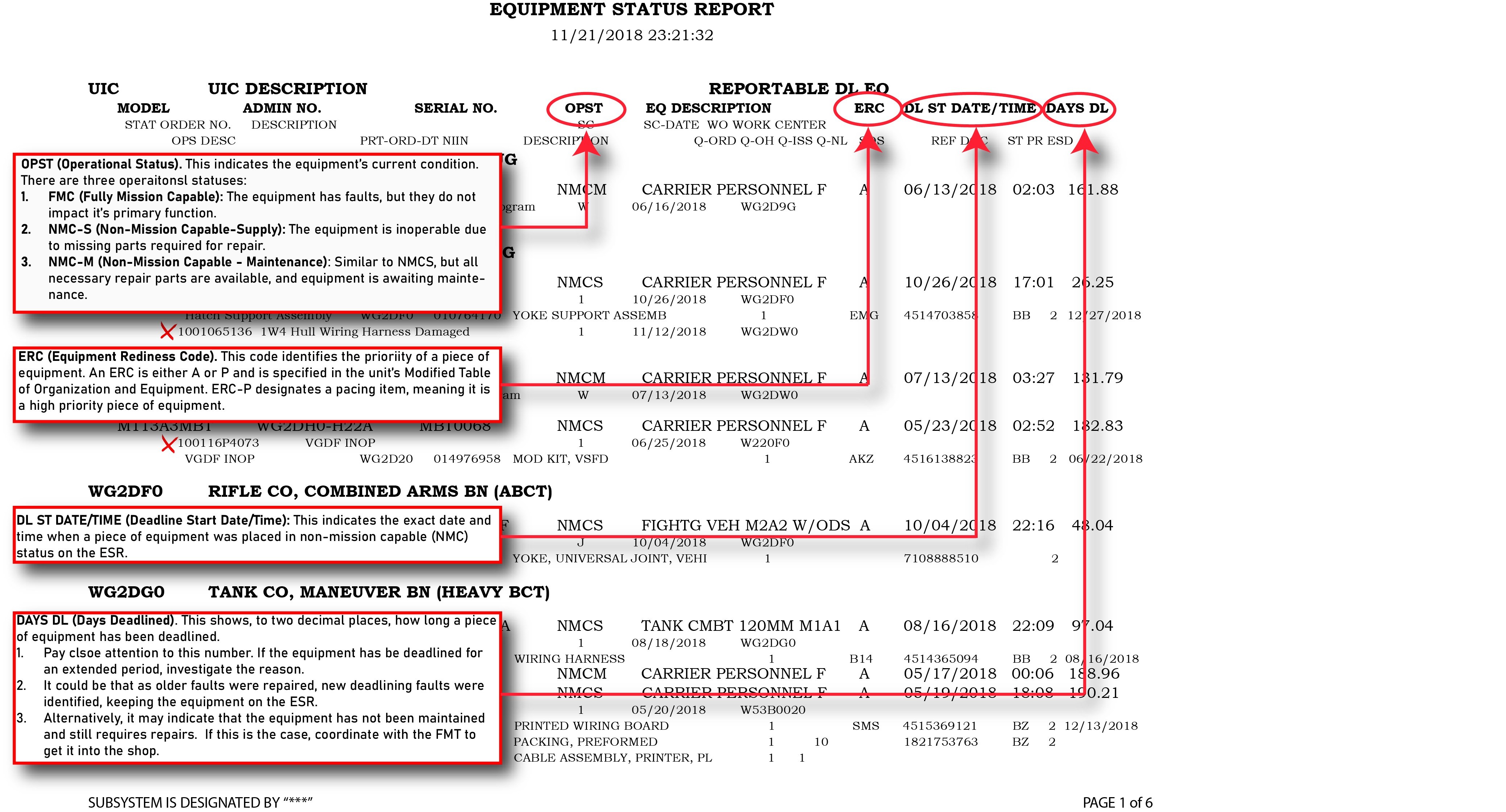

Of all the details on an ESR, there are a few that matter to platoon leaders the most. Their definitions, and how they can improve a maintenance program, are described in Figures 2 through Figure 5. The first four pieces of information are found in the second headlining row.

Figure 2. This example ESR shows the key information from the 2nd headlining row. (U.S. Army Graphic)

Platoon Maintenance SOPs and Best Practices

With the maintenance knowledge I’ve gained as a BMO, I often reflect on how I could have run a more effective platoon maintenance program. One of the key improvements I would have made is establishing structured maintenance SOPs, including weekly maintenance battle rhythm events, such as command maintenance days and platoon maintenance meetings.

Most platoons already participate in command maintenance days, often referred to as “Motor Pool Monday”, but these events could be more efficient and impactful. As a mechanized infantry platoon leader, I frequently had my mounted sections conducting preventative maintenance checks and services (PMCS) on our M2A3 Bradley Fighting Vehicles (BFVs), while my dismounts often had little to do. I now understand the critical importance of conducting weekly ancillary equipment maintenance by properly allocating priorities and manpower.

At a minimum, companies should prioritize ancillary equipment maintenance on a rotational basis. This can be achieved by platoon leaders working with the Company XO to create a four-week maintenance schedule, dedicating each week to a specific category of ancillary equipment:(4)

- Communications Equipment (e.g., radios and Joint Battle Command-Platforms [JBC-Ps])

- Weapons Systems

- Night Vision Devices (NVDs)

- All Other Platoon Equipment

During periods of increased manning, this schedule can be condensed, allowing more equipment to undergo PMCS each week. By proactively maintaining ancillary equipment, potential issues can be identified and resolved before field operations. Conducting after-operations PMCS for the first time post-field exercise is too late—preventative maintenance must be consistent and systematic to ensure operational readiness.

Communications equipment should be tested weekly through communications exercises (COMMEX) using radios and JBC-Ps. Even if higher headquarters does not mandate a weekly COMMEX, platoons should conduct them internally. The company communications representative can fill these systems, enabling platoons to conduct internal checks. Many units, including the 1st Cavalry Division, may already require a weekly COMMEX, making it essential to meet the commander’s intent.

Platoon maintenance meetings should be a weekly battle rhythm event. In 1-8 CAV, maintenance meetings are held at both the battalion and company levels, but they rely on information reported up from the platoons. Conducting platoon-level maintenance meetings fosters a shared understanding among the leadership and ensures platoon leaders are well-prepared to provide accurate briefings.

Platoon maintenance meetings should cover several key agenda items, with a primary focus on reviewing the ESR line by line. The platoon leader should facilitate the discussion, while section and squad leaders brief the faults for their assigned equipment. It is essential that platoon, section, and squad leaders understand the statuses of their equipment. Additionally, the radio-telephone operator (RTO) and armorer should assist in briefing the status of communications equipment and weapons. Ideally, all soldiers would be proficient in reading the ESR, but at a minimum, the platoon’s leadership, RTO, and armorer must be well-versed in it. When time allows, platoons should review the “wide open” ESR, which includes both deadline and non-deadline faults. Overemphasis on the NMC ESR often leads to neglecting slash faults, which can escalate into more severe equipment issues. The “wide open” ESR also provides visibility on open work orders, such as pending welding jobs, allowing soldiers to track ongoing repairs for their equipment.

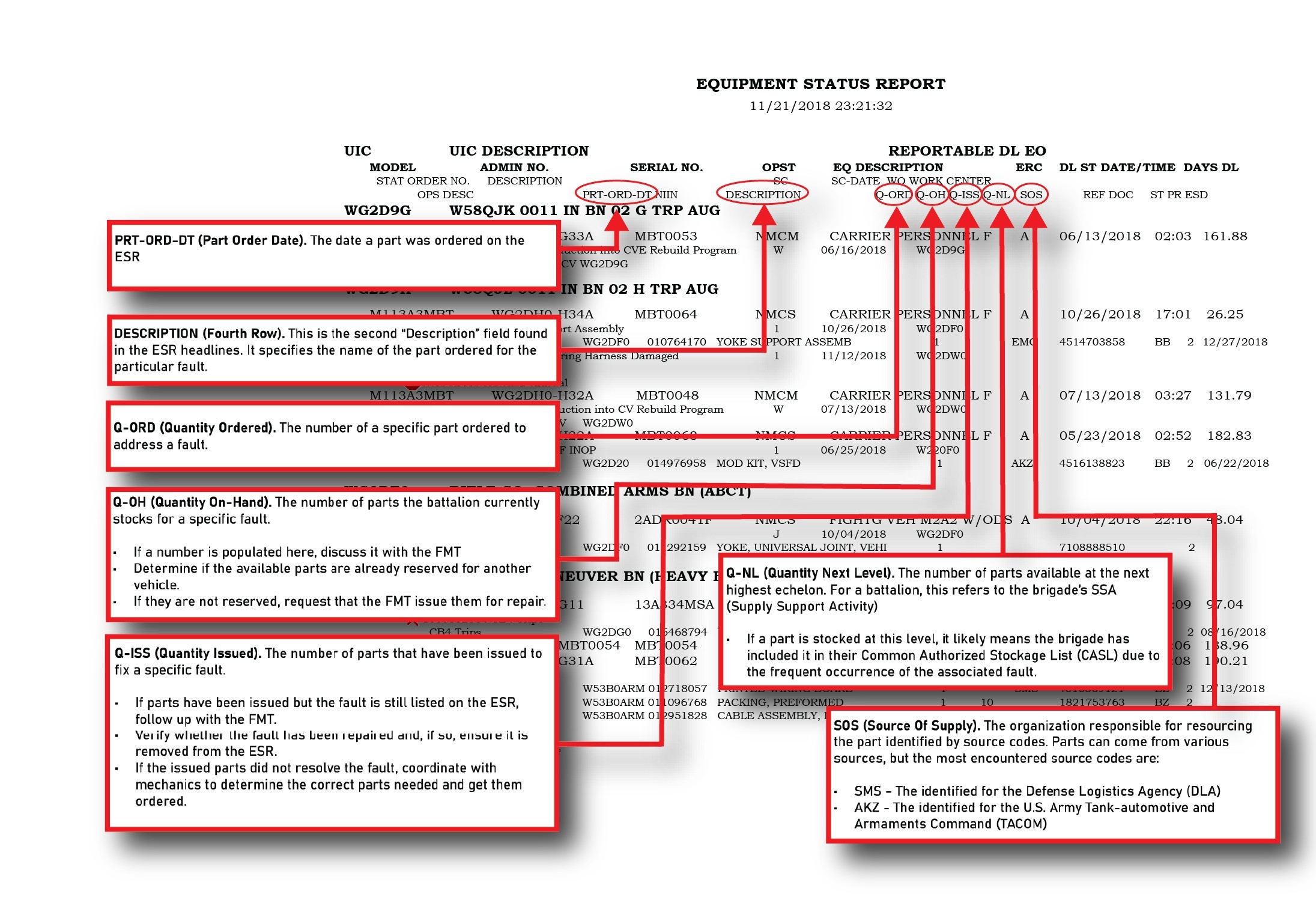

Figure 3. This example ESR shows the key information from the 3rd headlining row. (U.S. Army Graphic)

Services

Vehicle and equipment services should be another key agenda item in platoon maintenance meetings. Platoon leadership must understand the service schedule for each piece of equipment to prevent overdue services, as overdue equipment cannot be used until serviced.

Service plans consist of three key dates:

- Early Date – The earliest allowable completion date.

- Planned Date – The scheduled service date in GCSS-Army.

- Late Date – The latest allowable completion date before the equipment becomes delinquent.

The early and late dates represent a 10% variance window before and after the planned date in which the service must be completed. Completing a service before the early date can disrupt future service schedules by shifting them forward. Missing the late date results in delinquency without shifting the future service windows. Platoon leadership must also understand the steps involved in a service to track progress effectively. Battalion and company commanders may inquire about equipment status, and platoon leaders should be prepared to provide accurate updates.

Dispatches

Before a vehicle leaves the motor pool, it must be properly dispatched. Tracking open and overdue dispatches in platoon maintenance meetings ensures compliance and prevents unauthorized vehicle use. Dispatches serve as a commander’s tool to verify vehicles are FMC and maintain accountability for equipment assigned to different missions. Platoon leaders must ensure their crews process dispatches through the FMT clerk before vehicle use and properly close them upon mission completion. If a mission extends beyond the original dispatch window, the current dispatch must be closed, and a new dispatch packet must be completed in accordance with the unit’s dispatch SOP. To maintain accurate mileage records and prevent premature service triggers, soldiers should only approach the clerk to close a dispatch after recording the correct mileage in the dispatch book. This step ensures accurate mileage tracking under optimized service plans.

Figure 4. This example ESR shows the key information from the 4th headlining row. (U.S. Army Graphic)

Army units often require 10-mile road marches for each vehicle quarterly. This road march can be done in conjunction with training events as long as at least 10 miles are driven during the duration of the event. Some battalions prefer to make these road marches battle rhythm events on the calendar, whereas others leave it up to the companies and platoons. 1-8 CAV does not make it a battle rhythm event, but we track company adherence to this policy by including usage reports in our battalion maintenance meetings. As a trickle-down effect, our companies have included these reports in their company maintenance meetings. Usage reports can be pulled from GCSS-Army, and they are systems of record that display the distances travelled by vehicles during a selected period. This mileage is tracked by the change in odometer readings between dispatches, therefore making accurate mileage reporting extremely important when opening and closing dispatches.

Two other important metrics that should be tracked in platoon maintenance meetings are the Army Oil Analysis Program (AOAP) and test, measure, and diagnostic equipment (TMDE). AOAP monitors petroleum, oil, and lubricant (POL) samples to ensure vehicle health and identify engine, transmission, gearbox, or hydraulic failures before they occur8. Samples must be drawn and submitted at intervals prescribed by the AOAP lab and submitted for testing. The company XO can pull AOAP due dates from a program called the Army Enterprise Systems Integration Program (AESIP) for the platoon leader to include in their platoon maintenance meetings. TMDE is a list of parts, tools, and equipment that need to be calibrated at specific intervals to ensure they are accurate and effective9. Most of these items are owned at the company level, but some platoon equipment may need calibration. A platoon leader should confirm if any of their sub-hand receipt (SHR) is enrolled in TMDE and include their service dates in their platoon’s slides.

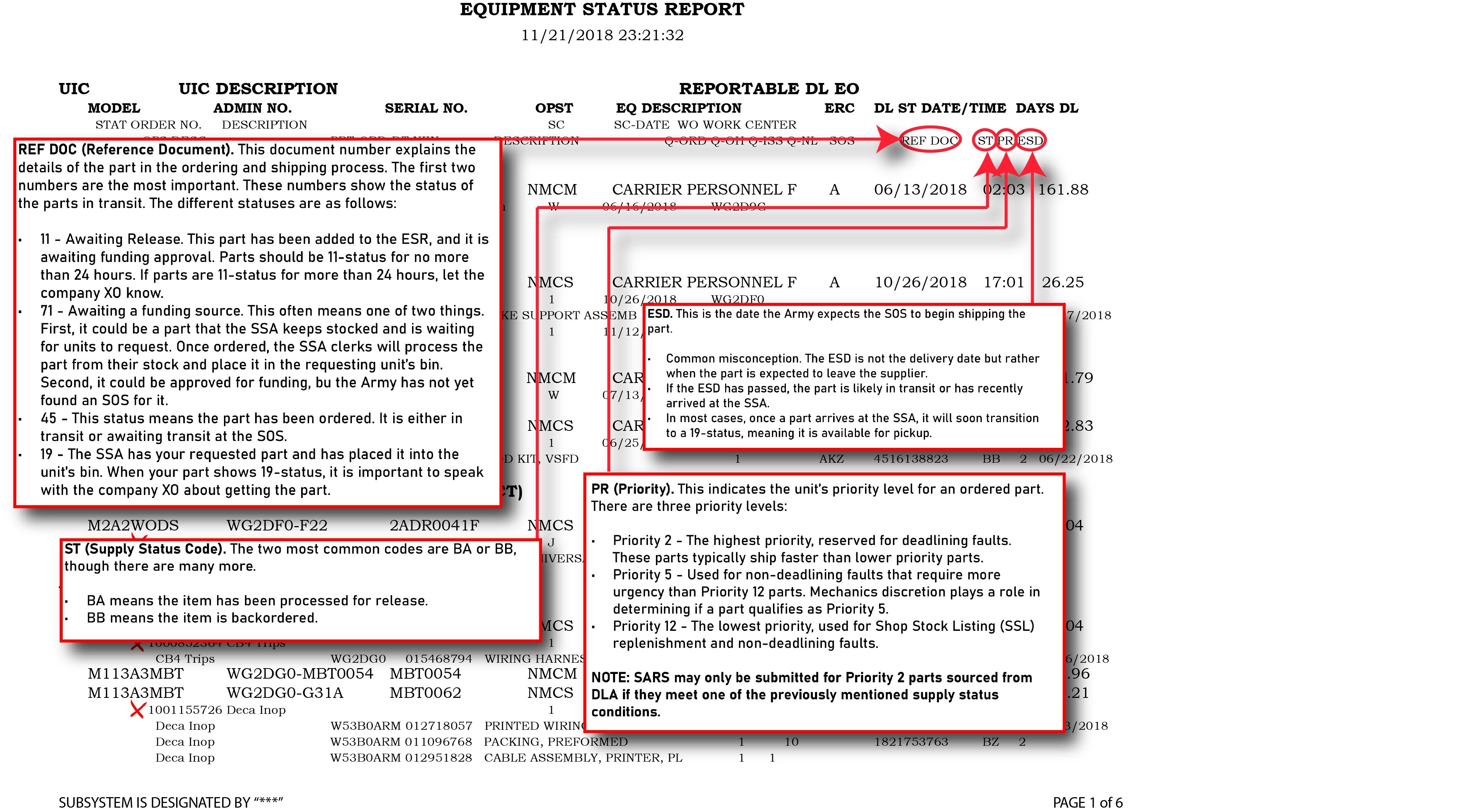

Figure 5. This example ESR shows additional key information from the 4th headlining row. (U.S. Army Graphic)

Another SOP that units should establish is Class IX (CL IX) management. CL IX is the Army’s class of supply for repair parts. CL IX management is often done at the battalion and company levels, but it should be done at the platoon level as well. For example, Combat Company, 1-8 CAV, dictated that only platoon leaders and platoon sergeants could sign for CL IX from the FMT non-commissioned officer in charge (NCOIC). This was to maintain better accountability of parts and ensure they were issued to the right vehicle. If a part was installed on the wrong vehicle, then the vehicle needing the part wasted a lot of time on the ESR. If the company does not have an SOP, then the platoon should establish one. Will only the platoon leader or platoon sergeant be able to sign for CL IX? Will section leaders be allowed to do it? My recommendation is that only the platoon leader and platoon sergeant sign for parts. This allows for better awareness and accountability within the platoon’s maintenance program.

Allowing the platoon’s soldiers to sign for parts makes CL IX management more difficult for the entire company. Crews may not know if the part they need was ordered for another vehicle. Additionally, when CL IX is issued for a vehicle, it needs to be installed immediately to fix the fault. If it is operator-level maintenance (maintenance that can be conducted per the 10-level technical manual [TM]), then members of the crew can apply the part. If it is mechanic-level maintenance (maintenance conducted per the 20-level TM), then a mechanic needs to hang the part. If a parts manual is available for that piece of equipment, then the source, maintenance, and recoverability (SMR) code can be checked in the maintenance allocation chart (MAC) to see who installs it. The SMR code has five characters. The third character, which is the maintenance code, identifies the maintenance level for replacement. A maintenance code of ‘C’ means a crew or operator can replace the part, and a maintenance code of ‘F’ means unit-level maintainers can replace the part. Sometimes ‘O’ is listed in place of ‘F’ in older MACs.(7)

Whenever a part is hung by a mechanic, whether in shop or on the motor pool line, a member of that vehicle’s crew needs to be present.

An important maintenance SOP affecting unit lethality is 24-hour maintenance when pacing equipment parts are received for deadline faults. If a part arrives that would make a pacing vehicle (commonly called a pacer) FMC, then continuous work needs to occur to make it happen. Maintenance will occur until the part is hung and the fault is fixed. The purpose is to remove the amount of time a pacer is on the ESR, and it helps improve the battalion’s operational readiness.

Unusable, recoverable parts removed from equipment join the overage repairable items list (ORIL). These parts need to be returned to the Army so they can be repaired and issued back out to the force. Units receive monetary credit back for parts turned in. ORILs are monitored at the battalion and brigade level, and poor management of these parts can cause a unit’s ORIL to be extremely long. Operators need to clean the parts and give them to their FMT clerks for turn-in. Platoon leaders should work with their Company XO to get a list of platoon ORILs to be tracked internally.

Field Maintenance

Field maintenance is probably one of the most overlooked aspects in maintenance. Soldiers tend to forget or avoid it until their equipment breaks. Field maintenance is often equated to cleaning weapons in the field, but it is so much more than that. Soldiers need to PMCS their equipment in the field daily. According to Army Regulation (AR) 25-30 Army Publishing Program, each piece of equipment is supposed to be accompanied by a TM.(8) When a Soldier draws a piece of equipment, they should draw the TM as well. TMs should remain in vehicles too. While the Army is beginning to modernize with all-in-one tablets that include both the TM and Department of the Army (DA) Form 5988-E, it is a good practice to maintain a paper copy of the TM in the vehicle. As long as those copies aren’t lost or destroyed, paper TMs are a great contingency for when tablets break or run out of battery.

There are three types of PMCS: before, during and after operations.(9) At a minimum, the during operations PMCS should be completed in the field daily. This will help crews identify problems before they become significant, and it gives the FMT a chance to fix them before more intensive maintenance is required.

Printing capabilities are usually extremely limited in the field. Therefore, platoon leaders should ask their XOs to bring several DA Form 5988-Es for each vehicle prior to starting a field problem. If printing is an option, XOs can ask for the forms in their daily logistics package (LOGPAC) requests. Soldiers should complete PMCS of their vehicles and equipment on these 5988s daily. Leaders throughout the platoon should spot check the accuracy of the PMCS, then they should be submitted to the XO. Conducting continuous field PMCS will allow both the FMT and the battalion’s maintenance enterprise to stay up to date on all maintenance issues within the unit.

Final Notes

A platoon leader should make it their priority to establish good relationships with their Company’s mechanics. They are the ones that keep the vehicles in the fight and their job is challenging. There are long hours, lots of physical work, and rarely any downtime. A platoon leader also needs to allow the FMT time to PMCS and maintain their own assigned vehicles. An FMT’s efficacy relies heavily upon its vehicles’ capabilities. If their M88 is NMC, they are unable to recover tracked vehicles. If their palletized load system (PLS) is down, they will be unable to bring their forward repair system (FRS) and field pack-up (FPU) container (also known as a BOH, after the company that makes them), into the fight. While it is important for a platoon to have faults verified and fixed promptly, time needs to be given to the FMT to do the same thing.

Maintenance can be an intimidating aspect of the Army to all leaders, but it is especially nerve-racking for new platoon leaders. If the proper focus and dedication is given to maintenance, it isn’t that scary. As a BMO, I believe that while maintenance perfection is impossible, an effective maintenance program is extremely achievable. To build an effective program at the platoon level, a platoon leader must study the ESR, ask maintenance questions to anyone who will listen, and be present in the motor pool. Units with effective maintenance programs, regardless of the echelon, are the most lethal. Lethality is like a house – training is the structure that builds lethality, but maintenance is the foundation on which it stands on. The house cannot last if there is no foundation.

Christian Arnett is a First Lieutenant currently serving as Executive Officer of a Military Intelligence Company within the Regimental Military Intelligence Battalion, 75th Ranger Regiment. Previous assignments include Battalion Maintenance Officer for 1st Battalion, 8th Cavalry Regiment, 2nd Armored Brigade Combat Team, 1st Cavalry Division, and Infantry Platoon Leader for C Company, 1st Battalion, 8th Cavalry Regiment, 2nd Armored Brigade Combat Team, 1st Cavalry Division. His military education includes Ranger School, Basic Airborne Course, Bradley Leader’s Course, and Infantry Basic Officer Leader Course, all completed at Fort Benning, Georgia. Arnett holds a Bachelor of Science in environmental engineering from the University of Iowa.

Notes

1 LTC Jay Ireland, “Peaking at LD: A Way to Achieve Maintenance Excellence,” Armor 135/4 (Fall 2023): 25-28, https://www.moore.army.mil/Armor/eARMOR/content/issues/2023/Fall/ARMOR Fall 2023.pdf

2 MG Jeffery Broadwater, COL Patrick Disney, and MAJ Allen Trujillo, “The Leader’s Guide to Creating a Daily Maintenance Battle Rhythm,” From the Green Notebook, 25 August 2020, https://fromthegreennotebook.com/2020/08/25/the-leaders-guide-to-creating-a-daily-maintenance-battle-rhythm/

3 “GCSS-Army Job Aid: Equipment Status Report (Z_EQUST)”, United States Government, 08 December 2018, https://gcss.army.mil/Training/WebBasedTraining

4 MAJ Gary M. Klein, “Operationalizing Command Maintenance to Train Organizational Systems and Build a Culture of Maintenance Readiness,” Armor 134/3 (Summer 2022): 19-24, https://www.moore.army.mil/Armor/eARMOR/content/issues/2022/Summer/ARMOR Summer 2022-optimized.pdf

5 “Army Oil Analysis Program (AOAP),” Army Sustainment Command, n.d., https://www.aschq.army.mil/Offices/Redstone-Detachment/

6 “About USATA,” U.S. Army TMDE Activity (USATA), 04 April 2024, https://tmdehome.redstone.army.mil/

7 Army Techniques Publications 4-33, Maintenance Operations, 09 January 2024, appendix C

8 Army Regulation 25-30, Army Publishing Program, 14 June 2021, paragraph 1-28

9 Army Regulation 750-1, Army Materiel Maintenance Policy, 02 February 2023

Social Sharing