If it weren’t for the construction of Libby Dam, in Libby, Montana, I’m not sure I’d be here today. I know for certain I wouldn’t be its natural resource manager. But more than that, I might not even exist.

The construction of Libby Dam set my life’s story in motion in a couple of ways.

My dad’s family hails from Choteau, Montana, about five hours from Libby Dam. In the early 1960s, steady job opportunities in Choteau were scarce, unless you were digging for dinosaur bones. My grandpa, Donald “Whitey” Wilson, wasn’t in the paleontology business, he was a construction man, recently out of the Navy, married and raising a growing family. He first moved to Hungry Horse, Montana, to work at the Columbia Falls Aluminum Plant, but not long after, in 1967 at 29 years old, he joined the Operating Engineers Union and was hired by Morrison-Knudsen as a batch plant operator during the dam’s construction.

For more than a year, Grandpa Whitey commuted daily from Hungry Horse to Libby, even during inclement winter months, in a yellow 1949 two-wheel-drive Ford truck. With the dam construction set to last several years (1966 – 1972), the Wilson family eventually relocated to Libby, putting down roots in the community. And that’s where my beginning stems from.

Though his work on the dam wrapped up in 1972, Grandpa Whitey remained in Libby working other construction projects. All the while, my dad grew up and attended Libby High School where he met my mom, a fourth-generation Libby native. Her father, Don Whitmarsh, “Papa” to his grandkids, also helped build Libby Dam. He started in 1965 as a young 22-year-old.

Stories like mine are not uncommon for the Libby Dam construction era. Families came from all over for the incredible job opportunities the project offered. While many moved on after the work was done, my grandparents stayed—and the rest, as they say, is history.

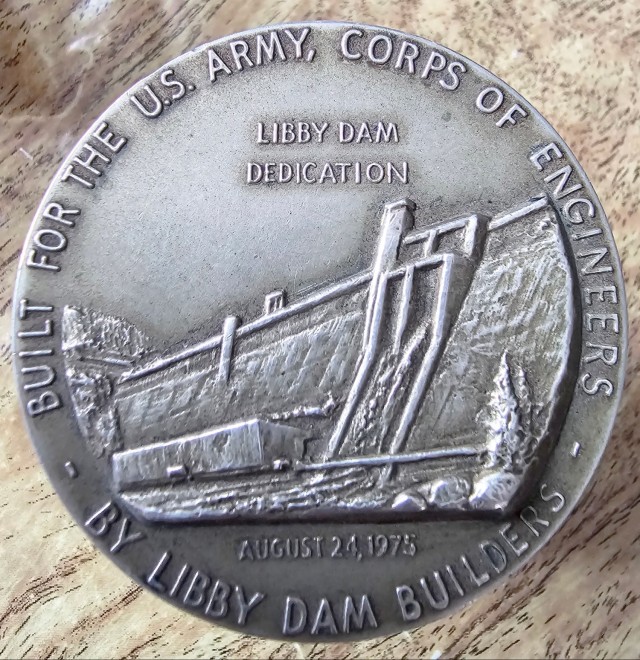

Now, 50 years since its completion, Libby Dam remains a cornerstone of Lincoln County, and my family’s name is still connected to its legacy.

I started working at Libby Dam right out of high school as a seasonal student worker. In Libby, there are a few typical summer job paths: U.S. Forest Service, Lincoln County or the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. Of the three, the Army Corps offered the fewest position opportunities, but I wanted in, whatever way I could get my foot in the door.

That way happened to be as a General Schedule 02 (GS-02) clerk, an entry-level role in the federal government, involving basic clerical tasks and requiring limited subject-matter knowledge.

For three summers, I scanned and archived over 10,000 construction-era photos, many of which are now featured in our 50th Commemoration celebrations, into a system called PastPerfect. It was monotonous work, but it served a need; it ultimately introduced me to the Army Corps’ recreation and environmental stewardship programs.

All told, I spent five summers working at Libby Dam while attending the University of Montana, Missoula, Montana, where I studied Parks, Tourism and Recreation Management, as well as Journalism. I later earned a Master of Science in Conservation Areas Management from Clemson University, Clemson, South Carolina.

After graduate school, I landed my first permanent Army Corps position with the Mill Creek Project in Walla Walla, Washington. I was there for a couple years before taking a promotion at John Day Dam on the Columbia River with Portland District.

I never thought I’d get the chance to move home and make a living in Libby. The old adage, “You have to move away to move home,” holds especially true in government work, and permanent job openings at Libby Dam, particularly in the natural resources field, are rare. But one became available and when I asked my Grandpa Whitey what he thought about my moving home, he said, “You’re a Montana mountain girl.”

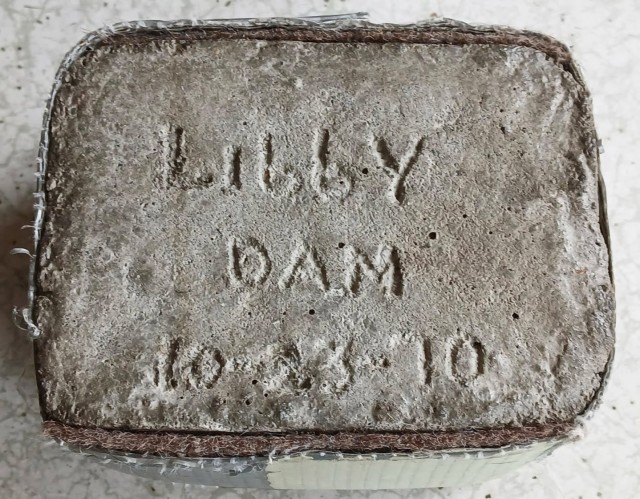

Grandpa Whitey passed away in August 2024. He was a proud man who kept a piece of Libby Dam concrete core with a Seattle District coin embedded in it displayed proudly in his glass cabinet at home. I’m grateful for the 30-plus years I have had with all my grandparents.

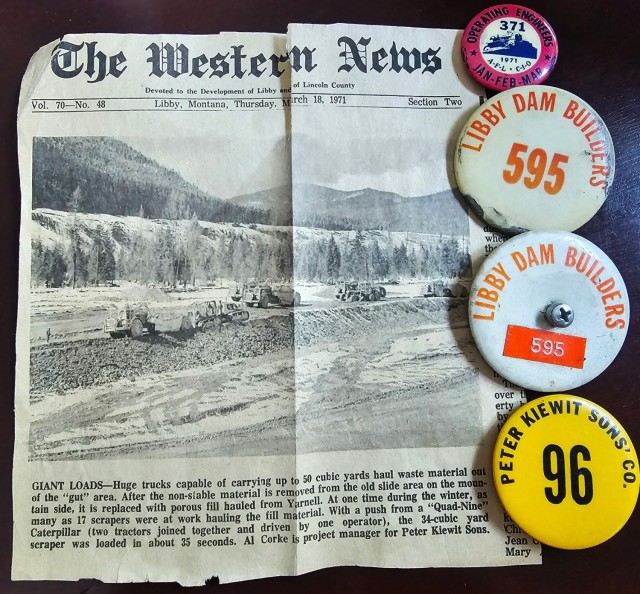

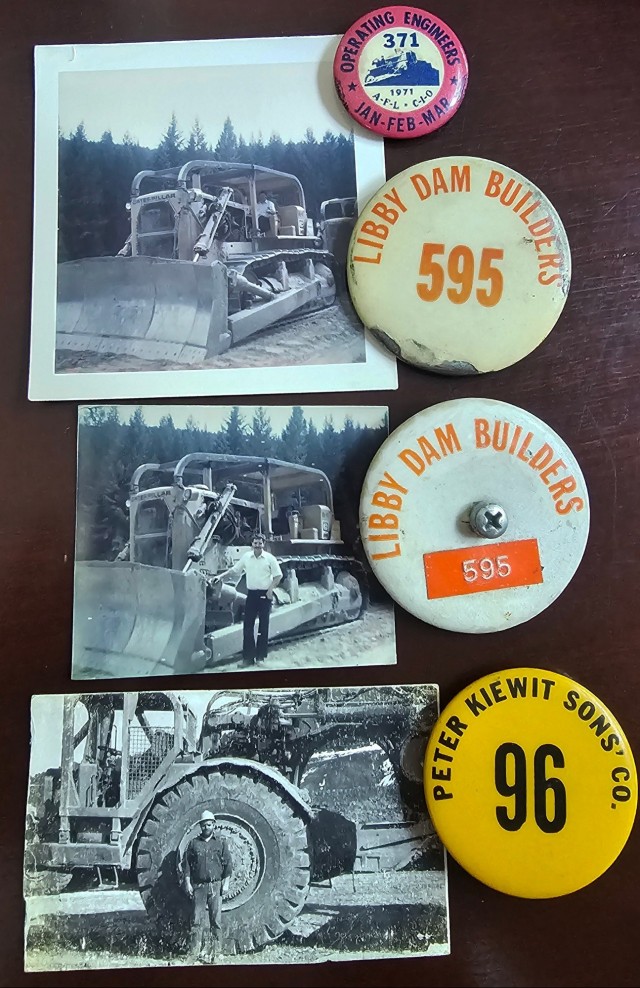

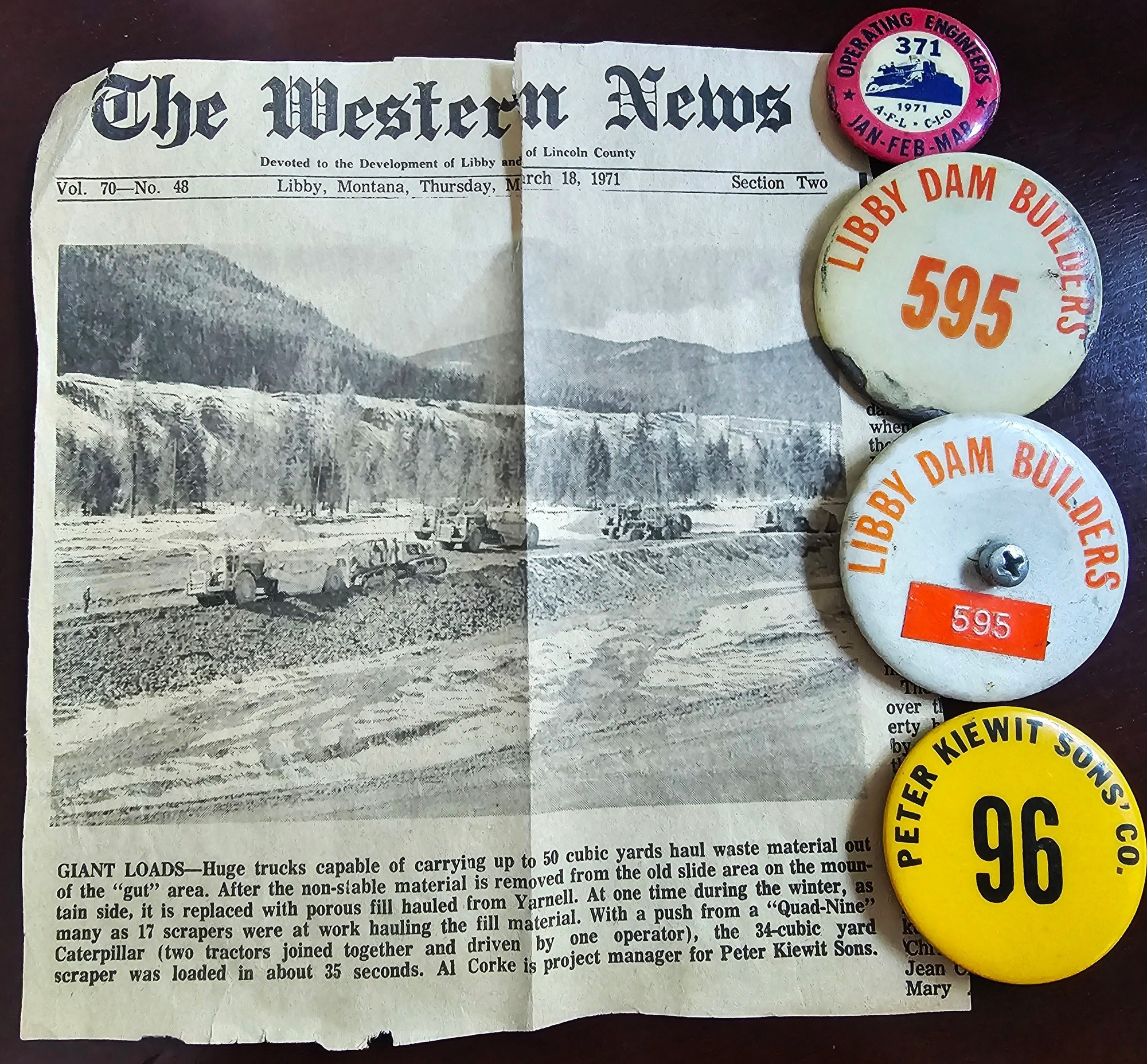

As Libby Dam commemorates its 50th year of operations, it’s been a fun excuse to talk to my Papa Whitmarsh about the early Dam days. Papa would clock in each day as “Libby Dam Builders 595.”

Papa was primarily an equipment operator for Kiewit and Sons Construction. He worked on the railroad tunnel and Highway 37 before joining the Libby Dam Builders, where he spent time on the dinky operating crew. It was hard work, but there was plenty of fun too.

While I wouldn’t recommend feeding wildlife, my park ranger background says, “No, No, No,” Papa amusedly recalled a large family of chipmunks that showed up every day during lunch break. They were fat, happy and clearly used to the attention. He called them “Rockmunks” because they were always darting around the boulders and rock outcroppings near the site.

Papa remembered the dam days as bustling in the summer. With around 2,000 workers on the job and construction running 24 hours a day, the whole area came alive. He said the local bars had live music every night of the week to keep up with folks’ energy. Winters, though, were quieter. It got too cold to pour concrete but there was always something to do, and Papa was glad to stay working year-round.

It’s pretty neat to look back at the dam’s construction, my family’s part in it and be in the natural resource manager seat, looking toward the future as we commemorate the past.

As I look toward Libby Dam’s future, my main goal as the natural resource manager is to balance visitor experience with resource protection for future generations.

One of the upcoming environmental stewardship projects I am most excited about is a logging operation near Dunn Creek Campground, Libby, Montana. Libby Dam manages about 2,000 USACE-owned acres including Dunn Creek Campground, which the Montana Department of Natural Resources and Conservation (Montana DNRC) identified in its Forest Action Plan as being at high risk for wildfire danger. Years of limited funding and forestry-focused staffing have hindered proactive land management, but in partnership with the DNRC, we’re now conducting the first large-scale Army Corps timber sale since the dam was built, a win-win for the forest and for public safety.

Another stewardship project that brings a lot of value to the recreating public and the river’s ecological function is our “Wood is Good” project, part of the USACE’s Engineering with Nature (EWN) initiative. This effort aims to enhance fish habitat in the Kootenai River below the dam by restoring the natural presence of large wood, that is blocked by the dam.

Since its completion in 1975, Libby Dam has maintained a robust tour program. It’s one of the few Army Corps operating projects still offering public tours into the powerhouse. I always knew Libby Dam was unique, but working at other USACE projects across the Pacific Northwest showed me just how special it really is.

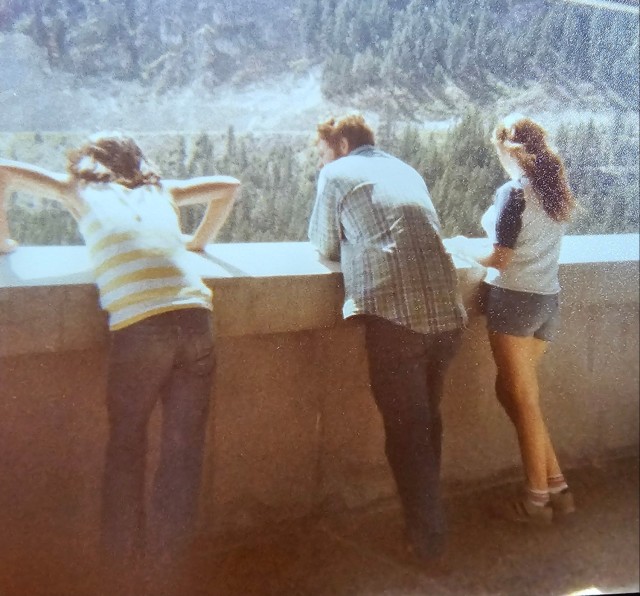

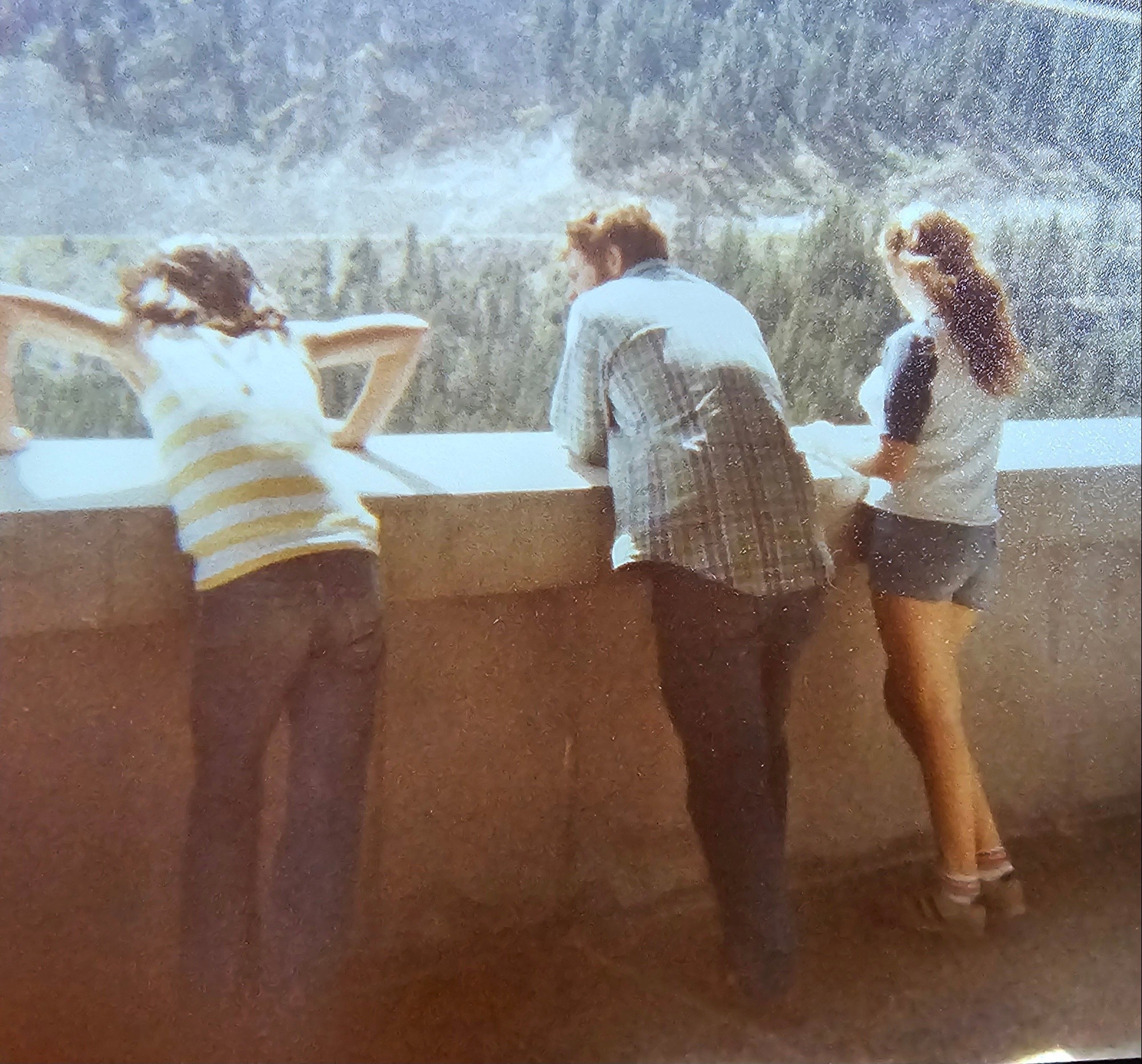

Libby Dam is also one of the last major hydropower dams built by the Army Corps and the only one designed by Paul Thiry, a famous architect and modernist known for his off-kilter angles. The dam is virtually free of right angles, an architectural wonder you have to see in person. I remember being quite little, six or seven, and my dad propping me up on the sloped concrete ledges so I could peek over and look 422 feet down to the Kootenai River.

That angle—and that view—stuck with me.

Growing up, both of my grandparents had little mementos from their time building Libby Dam, but it wasn’t until I started working for the Army Corps and at the dam that I had a trained eye to know. For example, Grandpa Whitey used a core sample with ‘Libby Dam’ etched on it as a door stopper for the backdoor leading to the yard. I must have kicked it out of the way a hundred times, never realizing the weight of the history it held. Papa Whitmarsh had his operator’s union and Libby Dam Builder buttons that displayed his individual identification numbers, common forms of onsite ID back then.

I have my own Libby Dam rite of passage: At the end of my final season as a summer student worker, I signed my name in the Cosmoline preserving grease inside Generator 8, ‘Tana 2012–2017.’

I didn’t know then that my career would lead me back to the Montana mountains, Libby Dam or even back in time for its 50-year milestone; one that subtly connects my grandparents’ work building the dam to my own work conserving the natural places that surround it.

Social Sharing