Following Russia’s failed attempt to seize Kyiv and decapitate the Ukrainian leadership in February 2022, the Russian Ministry of Defense was forced to withdraw elements of its Central and Eastern Military District forces through Belarus and back into Belgorod oblast in mid-to-late March. Rapidly reorganizing its forces and command and control (C2), these forces were reinserted and joined with elements of the Western and Southern Military Districts in April 2022 inside of Ukraine’s Donbas region, intent on capturing the entirety of the Luhansk and Donetsk oblasts.1

This reorganization allowed Russian forces to slowly grind away at Ukrainian defensive lines and ultimately allowed Russia to seize several strategic urban centers, including Izyum, Severodonetsk, and Lysychansk, before finally linking up its forces for the push to encircle the city of Bakhmut in May 2022.2 However, the significant losses suffered by Russian forces in both personnel, armored vehicles, and ammunition expenditure slowed Russia’s offensive actions and ability to capitalize on its momentum to seize Bakhmut. It would take Russian forces another two and half months to gather the forces needed to fully assault the city.

Ultimately, the battle for control of Bakhmut lasted more than nine months (from August 2022 until May 2023) and was one of the largest and most important battles of the second Russo-Ukrainian War. In many ways, this battle was reminiscent of the Ukrainian armed forces’ (UAF’s) heroic defense during the battle of Donetsk Airport in May 2014, which would forever label its defenders the “cyborgs.” However, the battle of Bakhmut brought forth a long-lasting dilemma in wartime stratagem: When if ever is a battlefield loss acceptable for the overall wartime strategy?

During the battle, Ukrainian forces were commanded by then-Colonel General Okeksandr Syrskyi, who now serves as UAF’s overall commander in chief following the removal of General Valerii Zaluzhnyi. Syrskyi has been hailed a hero for leading the defense of Kyiv during the initial Russian invasion in February 2022 and later the highly successful Kharkiv counteroffensive in the summer of the same year.3 However, he has also been labeled the “butcher of Bakhmut” for the staunch and determined defense of the city of Bakhmut and his apparent refusal to concede the city to attacking Russian forces. This strategy led to significant casualties amongst the UAF and the Russian attackers alike.

The Ukrainian forces comprised elements of the 24th, 57th, and 58th Mechanized Brigades; the 4th Tank Brigade; the 46th and 77th Airmobile Brigades; the 128th Mountain Brigade; several separate National Guard battalions; and the 3rd Separate Assault Brigade.4

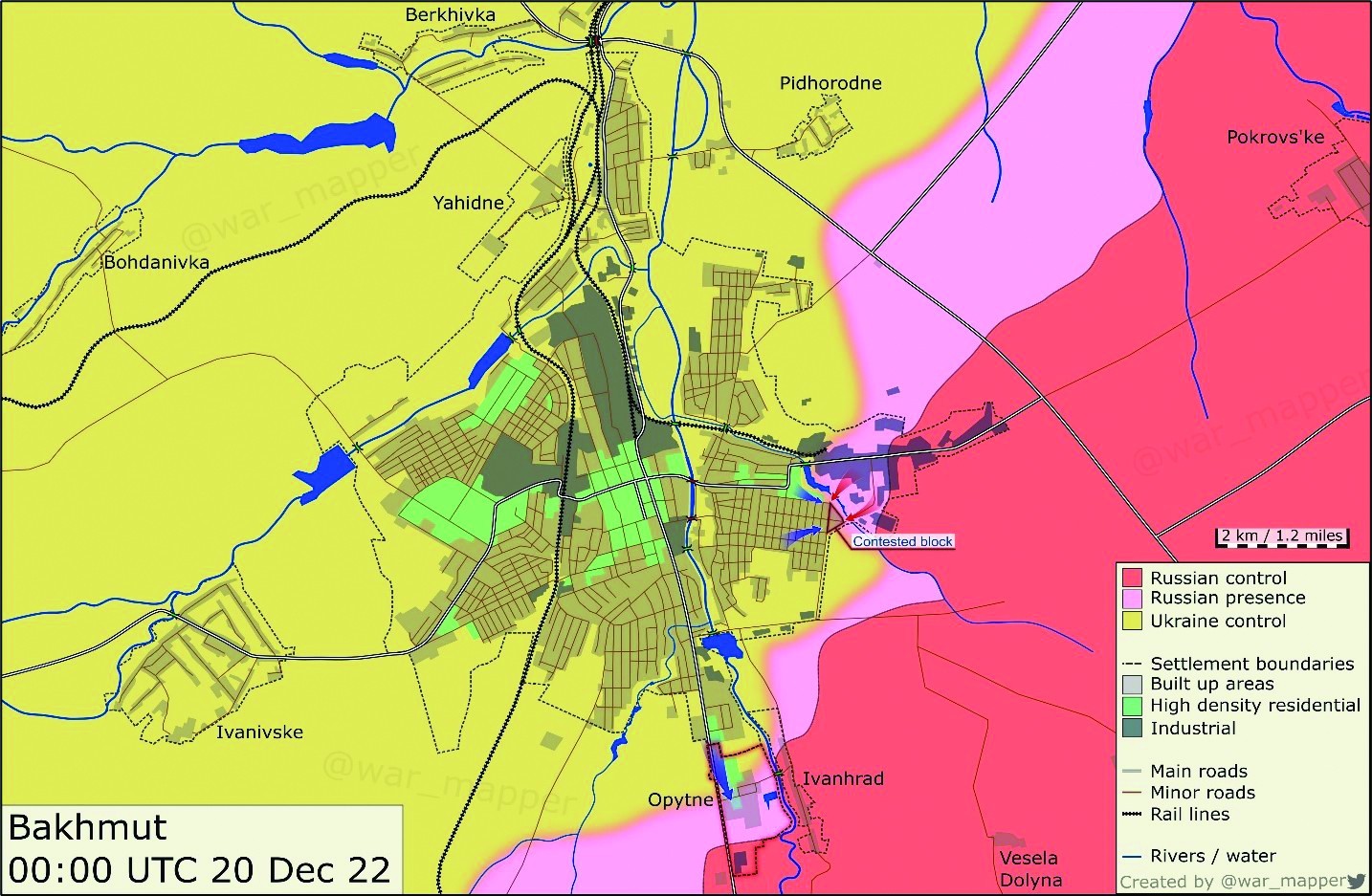

The forward line of troops as Russian forces continued their attempts to encircle the city and break through Ukrainian defensive lines (Map overlay courtesy of @war_mapper)5 VIEW ORIGINAL

The Russian forces were composed primarily of Russia’s private military company (PMC) Wagner, elements of Russia’s 31st Guard Air Assault Brigade, or airborne forces (better known as the VDV), elements of the 132nd Separate Motorized Rifle Brigade (Donetsk Peoples Republic [DNR]), 72nd Motorized Rifle Brigade, and Russia’s 3rd Army Corps.

In early August 2022, most of the fighting took place primarily on the eastern and southern outskirts of the city which had become a mixture of frenzied close quarters trench warfare and unfathomable artillery duels. Some Ukrainian officials claimed that Russian forces were firing up to 50,000 artillery shells a day compared to Ukraine’s 6,000 or less.6 While Russian forces were able to make isolated tactical breakthroughs of Ukrainian lines in early August, the determined defense by the UAF saw the Russian forces lose their momentum and forced to rely on waves of infantry assaults lacking effective armor support.

These assault forces were eventually arranged into assault detachments (Штурмовые отряды) and were more commonly referred to as Shtorm assault detachments, depending on their personnel composition.7 Shtorm-Z units were composed primarily of Russian prisoners recruited by Wagner PMC to fight in Ukraine to receive presidential pardons for their service. However, in its implementation many of these prisoners and assault detachments would not live to receive pardons as they were being annihilated in “meat wave” attacks. These human-wave attacks did however demonstrate the resolve of Russia’s military and political leadership to seize the city at any cost.8

By the end of August, while Russian forces continued to run headlong into Ukrainian mine fields and endless small arms engagements in Bakhmut, the UAF launched its counteroffensive, which focused primarily on the country’s southern regions of Kherson and Mykolaiv where it attempted to push the Russians back over the Dnipro and Inhulets rivers into southern Kherson and Zaporizhzhia. Ukraine’s southern counteroffensive proved slow going as Russian elements of the 247th Guards Air Assault Regiment and 810th Separate Naval Infantry Brigade led a determined delaying action in which the majority of the Russian forces were able to evacuate their heavy equipment and move to the left bank of the Dnipro River at the expense of heavy losses within the 247th and 810th.

While Russia’s focus was simultaneously focused on the outcome of Bakhmut and attempting to stem the tide of Ukrainian offensive actions in Kherson, Ukraine launched a surprise attack in Kharkiv oblast, forcing the Russians into a rapid retreat. The success of this counteroffensive was likely as much a surprise to the UAF as it was to the Russian ground forces as Ukrainian lightly armored and mobile forces were able to rout weak Russian defenses and effectively disrupt tactical and operational Russian C2.

Vaguely reminiscent of the U.S. Army and Marine Corps thunder-run tactics in Operation Iraqi Freedom, the decentralized but initiative-supported nature of the UAF assault saw Ukraine liberate as much territory in just a few days as Russian ground forces had taken months of sustained combat operations to occupy.9 Russian Major General Igor Konashenko would later state that the Russian troops in the areas of Izyum and Balakliia had regrouped to the Donetsk region in order to “increase efforts in the Donetsk direction.”10

The Ukrainian Kharkiv counteroffensive culminated in early October 2022, having pushed the Russian ground forces back over the Oskil River in eastern Ukraine and in some cases in northeastern Kharkiv back over the Russia-Ukraine border. Using the river as a natural barrier, the UAF was forced to slow its advance so as not to overly extend its logistical and C2 lines. A month later, Russian General Sergey Surovikin ordered the withdrawal of Russian forces from the right bank of the Dnipro River, effectively ending Russian presence in Kherson city.

As a result of Russia’s inability to strategize an effective defense in Kherson, while simultaneously throwing waves of prisoners and volunteer Wagner contractors into the meatgrinder of Bakhmut, the UAF was able to gain the momentum and capitalize on Russia’s overly centralized and impotent C2 structure. While Moscow attempted to micromanage battlefield developments, Russian commanders on the ground left openings in their defense in Kharkiv and were forced to relocate forces to both Kherson and Bakhmut.

As a result, Bakhmut became not only a struggle between Ukrainian and Russian forces but also an ideological battle between PMC Wagner’s owner Yevgeny Prigozhin, the Russian Minister of Defence (MOD), and Russian ground commanders such as the commanding general of Russian ground forces (Surovikin), commanding general of VDV forces (General Mikhail Yuryevich Teplinsky), and commander of the 58th Combined Arms Army (General Ivan Ivanovich Popov).11-13

While Bakhmut would ultimately fall to Prigozhin’s Wagner forces in May 2023, it had become the focal point for the entire conflict. Prigozhin would go onto claim that Wagner and Russian ground forces had suffered 20,000 killed in action, whereas the UAF had lost more than 50,000 with the same number of wounded personnel.14-15 The disgruntled PMC owner’s belief that the Russian MOD and Chief of the General Staff Valery Vasilyevich Gerasimov had intentionally delayed ammunition deliveries in order to reduce Wagner’s offensive ability would have disastrous results.16-17

Whatever celebrations the MOD had planned on having because of their victory in Bakhmut were short lived as only a month later Prigozhin and Wagner PMC, along with a small smattering of followers in nearby Russian ground forces, launched an ill-fated rebellion. The rebellion began first by taking over the Southern Military District headquarters in Rostov-on-Don before moving on to Moscow. For reasons likely to remain unknown, Prigozhin ended Wagner’s march just short of Moscow and recalled his forces, entering into negotiations with Putin’s regime and the MOD.

Today, Wagner is a shell of its former self, being stripped apart and replaced by the Russian MOD. Prigozhin and several of his followers were killed when his plane exploded under mysterious circumstances.18 The nine hard months of sustained combat operations in Bakhmut were costly for both Ukraine and Russia, and while Russia can claim to have achieved a tactical victory in securing the city, Ukraine ultimately won the strategic battle. The battle enabled Ukraine to liberate large swaths of territory in Kharkiv and Kherson, soaking up Russian reserves in both the VDV and the Wagner group. Prigozhin’s pride was in no small part to blame for this costly effect, wanting to outshine Russian commanders and the MOD who had lost both Kherson and Kharkiv.

Bakhmut was also an eye-opening battle for both the UAF and the Russian ground forces as it reduced the ability of artillery and mechanized forces to effect more than punishing strikes. The battle for the city was in effect one of the largest rifle engagements of modern warfare with both sides fighting for mere meters a day at grenade range between fighting positions.19 Called the bloodiest infantry battle since World War II, the battle of Bakhmut demonstrated that a determined infantry force effectively utilizing commercial off-the-shelf unmanned aerial systems, drone-dropped munitions, automatic grenade launchers, and a known urban environment was able to reap devastating consequences on the assault enemy force. The battle for Bakhmut would ultimately set the stage for the entire conflict and the tactics, techniques, and procedures of future infantry engagements between the UAF and the Russian ground forces.

Refusing to change tactics, the Russians ground their forces against Ukrainian defenders, looking to squeeze one final victory out of the winter battles of 2022-2023. This in turn allowed Ukraine time and space to train and equip reserve brigades while strategizing its plan for the 2023 summer counteroffensive.20 The views and opinions on how Ukraine defended Bakhmut differ greatly, but the fact remains that Russia has struggled for more than 19 months since the battle first started to make any significant advance past the city or along the entirety of the Donbas, with the exception of the capture of Avdiivka in February 2024.

While western analysts may try to pick apart the battle and the strategy employed by the Ukrainian political and military leaders, the final determination of whether the cost was worth the effort lies entirely with the Ukrainian people. What Russia lost in Bakhmut, it has been unable to regain — significant battlefield momentum. Today Bakhmut lies in ruins, a monument, or rather a tomb, of failed Russian ambitions, and as President Zelensky has stated, Bakhmut now lives “only in our hearts.”21

Notes

1 Frederick W. Kagan, George Barros, and Karolina Hird, “Russian Offensive Campaign Assessment,” 3 April 2022, Institute for the Study of War (ISW), https://www.understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign-assessment-april-3.

2 Kateryna Stepanenko, “The Kremlin’s Pyrrhic Victory in Bakhmut: A Retrospective on the Battle for Bakhmut,” ISW and American Enterprise Institute’s Critical Threats Project, 24 May 2023.

3 Mick Ryan, “A Tale of Three Generals — How the Ukrainian Military Turned the Tide,” Engelsberg Ideas, 14 October 2022, https://engelsbergideas.com/essays/a-tale-of-two-generals-how-the-ukrainian-military-turned-the-tide/.

4 David Axe, “Bakhmut Is ‘Soaked in Blood’ as Eight of Ukraine’s Best Brigades Battle 40,000 Former Russian Prisoners,” Forbes, 22 December 2022; https://www.forbes.com/sites/davidaxe/2022/12/22/bakhmut-is-soaked-in-blood-as-eight-of-ukraines-best-brigades-battle-40000-former-russian-prisoners/?sh=7c611f886f23.

5 “Zelensky in Bakhmut, Girkin Mocks Putin, Russia Moves Tanks in Belarus to Ukrainian Border. What Happened on the Front Line on December 20?” The Insider, 21 December 2022, https://theins.ru/en/news/258029m.

6 Marc Santora, “The Battle of Bakhmut, in Photos,” The New York Times, 23 May 2023, https://www.nytimes.com/2023/05/23/world/europe/bakhmut-photos-ukraine.html.

7 Jack Watling and Nick Reynolds, “Meatgrinder: Russian Tactics in the Second Year of Its Invasion of Ukraine,” Royal United Services Institute (RUSI) for Defense and Security Studies, 19 May 2023.

8 Polina Nikolskaya and Maria Tsvetkova, “‘They’re Just Meat’: Russia Deploys Punishment Battalions in Echo of Stalin,” Reuters, 3 October 2023, https://www.reuters.com/world/europe/theyre-just-meat-russia-deploys-punishment-battalions-echo-stalin-2023-10-03/.

9 Henry Foy, Sam Joiner, Sam Learner, and Caroline Nevitt, “The 90km Journey that Changed the Course of the War in Ukraine,” Financial Times, 28 September 2022, https://ig.ft.com/ukraine-counteroffensive/.

10 Sergei Kuznetsov, “Russian Forces in Full Retreat from Kharkiv as Ukraine Seeks to Turn Tide of War,” Politico, 10 September 2022, https://www.politico.eu/article/russian-forces-in-full-retreat-as-ukraine-seeks-to-turn-tide-of-war/.

11 Kartapolov commented on the removal of Major General Popov after a report on problems in the army in an article in the Kommersant Daily, 13 July 2023, https://www.kommersant.ru/doc/6098125.

12 Ellie Cook, “Russia Reinstates Key Commander Amid ‘Intense Tensions’ Over Ukraine: U.K.,” Newsweek, 16 April 2023, https://www.newsweek.com/russia-reinstate-mikhail-teplinsky-tensions-ukraine-1794610.

13 Gilbert W. Merkx, “Russia’s War in Ukraine: Two Decisive Factors,” Journal of Advanced Military Studies 14/2 (2023), https://muse.jhu.edu/pub/419/article/909028.

14 “Prigozhin: 20 Thousand Soldiers of the Wagner PMC Died in the Battles for Bakhmut,” Kommersant Daily, 24 May 2023, https://www.kommersant.ru/doc/6001275.

15 Nicholas Camut, “Over 20,000 Wagner Troops Killed, 40,000 Wounded in Ukraine: Prigozhin-Linked Channel,” Politico, 20 July 2023, https://www.politico.eu/article/russia-ukraine-war-over-20000-wagner-troops-were-killed-prigozhin/.

16 Jake Cordell, ed. Gareth Jones, “Russia’s Prigozhin Renews Appeal for More Ammunition to Seize City of Bakhmut,” Reuters, 1 May 2023, https://www.reuters.com/world/europe/russias-prigozhin-renews-appeal-more-ammunition-seize-city-bakhmut-2023-05-01/.

17 Andrew Osborn, “Russian Mercenary Chief Says He’s Been Told to Stay in Bakhmut or Be Branded Traitor,” Reuters, 9 May 2023, https://www.reuters.com/world/europe/head-russias-wagner-group-says-still-no-sign-promised-ammunition-2023-05-09/.

18 Shamsher S. Bhangal, “The Wagner Rebellion and the Stability of the Russian State,” The Wilson Center, 21 September 2023, https://www.wilsoncenter.org/blog-post/wagner-rebellion-and-stability-russian-state.

19 RadioFreeEurope journalists, “The Battle for Bakhmut: The Bloodiest Infantry Brawl Since World War II,” RadioFreeEurope, 6 April 2023, https://www.rferl.org/a/ukraine-russia-battle-bakhmut-ruins-/32351803.html.

20 Mariano Zafra and Jon McClure, “Four Factors that Stalled Ukraine’s Counteroffensive,” Reuters, 21 December 2023, https://www.reuters.com/graphics/ukraine-crisis/maps/klvygwawavg/#uncovering-the-extensive-destruction-of-bakhmut-in-a-new-detailed-analysis.

21 Susie Blann and Zeke Miller, “Zelenskyy Says ‘Bakhmut is Only in Our Hearts’ after Russia Claims Control of Ukrainian City,” Associated Press, 21 May 2023, https://apnews.com/article/bakhmut-russia-ukraine-wagner-prigozhin-da2fc05b818b3dcc39decd40b17d2d8b.

Bryan Powers is a U.S. Army veteran with more than a decade of service including four deployments to Iraq, Afghanistan, and Jordan. He is the author of The Bloody Path to Valkyrie: How Duty, Faith, and Honor Inspired the German Resistance 1933-1946. Mr. Powers continues to serve the U.S. Army as a civilian and lives in Virginia, where he and his wife strive to continue their work in writing and in humanitarian support efforts for the Ukrainian people.

This article appeared in the Spring 2025 issue of Infantry. Read more articles from the professional bulletin of the U.S. Army Infantry at https://www.benning.army.mil/Infantry/Magazine/ or https://www.lineofdeparture.army.mil/Journals/Infantry/.

As with all Infantry articles, the views herein are those of the author and not necessarily those of the Department of Defense or any element of it.

Social Sharing