As a new infantry lieutenant, I thought I knew what the first few years of my career would look like. I would spend a few months in the operations and training staff section (S-3), get a platoon, and become an executive officer (XO) or even a specialty platoon leader. But on my first day at the 5th Battalion, 20th Infantry Regiment, my battalion XO dragged me into the logistics and sustainment staff section (S-4). What was initially supposed to be “a couple of weeks to help them catch up on some work” very quickly turned into a couple of months. Before I knew it, I was the S-4 officer in charge (OIC).

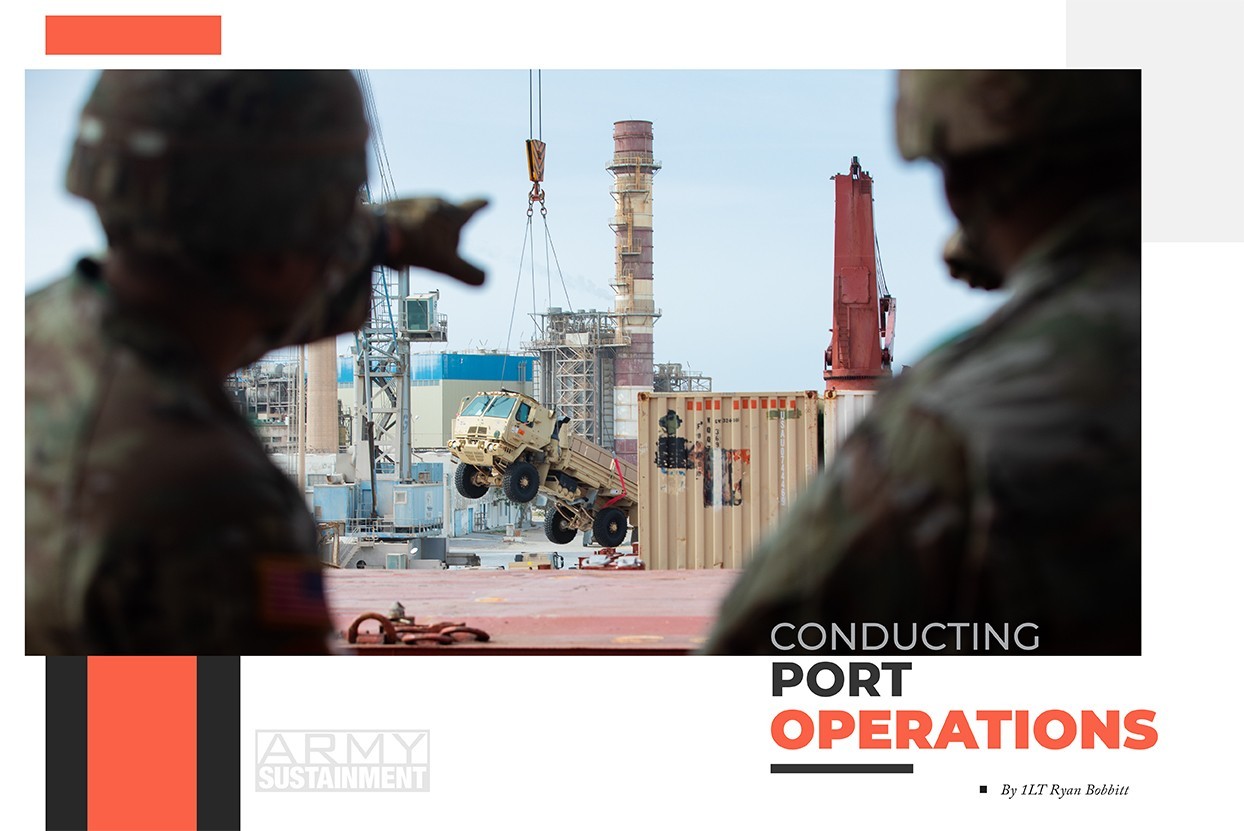

The battalion was about to participate in Orient Shield 2023, a yearly joint exercise between the U.S. and our Japanese allies. We were going to Japan. This exercise was a trial by fire in my new role. Between sustaining the battalion and managing life support contracts and purchases abroad, I gained tons of experience and learned new things daily. Port operations are the most critical, costly, and high-risk part of deploying a unit across the Pacific. If a unit cannot successfully deploy its equipment, it does not matter how good its operations or sustainment planning are. It is a critical mission, and we must know how to do it well. And somehow, with no experience in this subject, I found myself responsible for the success or failure of this small part of our bigger mission. Ensuring success at a port cannot be guaranteed. Still, with proper planning and preparation, you can get your unit’s equipment where it needs to be on time and safely.

The first step in ensuring success at the port is assembling the correct team to execute and manage operations. The OIC and NCOIC are responsible for the operations. You need at least one Soldier qualified as a unit movement officer (UMO), preferably an officer or senior NCO. Several UMO-qualified Soldiers are a must for larger operations. A designated UMO rep from each subordinate unit is the best way to manage large battalion or brigade movements. The team needs hazardous material (HAZMAT) certifiers. The number of HAZMAT Soldiers needed depends on the number of HAZMAT containers you have. Vehicle crews are the bulk of your workforce. Having the correct number of crews to drive vehicles (and ground guide) around the port and on/off ships is necessary to ensure your load rate is high enough. Everything at the port costs money. It costs money to keep the ship docked, to keep vehicles parked on the docks, and to pay the countless workers around the clock. This money is not coming directly out of your pocket, but for every minute wasted, the Army is paying a bill, and someone will want answers.

The second step is having the correct paperwork at the port. Whether you are embarking or debarking, your paperwork should look very similar. You must have several copies of your unit deployment list (UDL). This complete UDL should include transportation control numbers (TCNs), bumper numbers, models, nomenclature, dimensions, and serial numbers. Out of all this information, the one that matters the most is the TCN. The TCN controls everything. It is a unique code that each piece of equipment gets, and that is how load plans are built.

In addition to the UDL, you or someone on your team needs to have access to the website Transportation Coordinator’s Automated Information for Movements System (TC-AIMS). TC-AIMS is the unclassified system where units provide their inputs for movements and deployments. The battalion S-4 or UMO can help get you this access. TC-AIMS is how UDLs are constructed; every piece of equipment is built into this system and added to the UDL. Nothing should change during port operations on the UDL, but it can be a helpful tool to pull data if needed.

A designated HAZMAT-certified Soldier needs to have the required paperwork for every HAZMAT container. At a minimum, this paperwork needs to include a DD Form 2890, DoD Multimodal Dangerous Goods Declaration; a safety data sheet; and an Emergency Response Guidebook. HAZMAT on rail or linehaul also needs to have a DD Form 626, Motor Vehicle Inspection (Transporting Hazardous & Sensitive Materials). The HAZMAT representative at the port needs to have at least five copies of each. Every sensitive item container has a corresponding DD Form 1907, Signature and Tally Record, which shows a chain of responsibility for the containers. A member of the port team needs copies of this form as well. The DD Form 1750, Packing List, records the contents of each container. Again, you need copies of these. While it is essential to have hardcopies, it is incredibly beneficial to use a shared drive or another Army system to store these files digitally. Everyone at the port will want copies of this paperwork, so the team needs to know where to pull the paperwork from in case you run out.

Like airliners at an airport, ships have delays. Sometimes they arrive early; sometimes they arrive late. Unlike an airport, no monitors or signs show you exactly when and where your ship will arrive. It is essential to remain flexible. There is too much that is out of your control for you to always stay exactly on the timeline. There are plenty of things that are within your control. Working at a port, similar to working at a railhead, is not exciting for most, especially for your young Soldiers who spend long days driving, walking, and dealing with countless inconvenient problems. Many of these young Soldiers do not always see the immediate importance of what you are doing. As with any Army operation, it is crucial to provide priority, task, purpose, and the why. Setting these conditions early, with good NCO support, will significantly alleviate many headaches.

While you can scramble to get another driver to the port or fix some paperwork on the spot, the one thing you cannot fix is lost equipment. You must track everything. You need to know where each container and vehicle is parked. You need to know when and where they are being loaded. On the back end, you need to know what vehicles are convoying, what vehicles are getting loaded on rail, and what vehicles are being moved by commercial line haul. Everything must be tracked and recorded. For larger moves, it is inevitable that, at some point, someone will lose contact with a piece of equipment. When this happens, the port OIC will probably be the first to receive a phone call. It is imperative that, just like in tactical operations, you have a cell responsible for battle tracking 24/7. Depending on the scale of your move, your battalion S-3 shop should have some young lieutenants and captains perfect for this job.

The OIC and NCOIC need to stay very closely tied with their point of contact (POC) at the port. In Japan, there was a Japanese civilian who saved me many times. Having a good relationship with your POC should not start when you get there. You need to get in contact early. Early contact sets you up for success. At most ports, the civilians rule all. It does not matter how squared away you think your paperwork is. If they say no-go, it is a no-go. This is another essential thing to emphasize to your entire team at the port. A Soldier and a port civilian fighting about a DD 1750 is the last thing you need.

Your POC is not always a civilian; it could be a Soldier working full-time at the port or a mobility warrant officer. Regardless, there is one person you are given upon arrival who has the answers to all your questions. They know the vessel timeline, and you must get this timeline quickly to do your backward planning. As mentioned above, this timeline changes often, so it is essential to ask daily about any changes. You need to have at least one daily touchpoint with your POC. They can answer your questions, provide guidance, and prioritize the next day’s tasks. More important, they tell you if you are on or off track.

Port operations are not difficult to conduct. With the correct team and the right paperwork, you can fix any problem that arises. If you manage your equipment and prioritize safety and control, the rest will fall into place.

--------------------

1LT Ryan Bobbitt is currently a platoon leader in the 5th Battalion, 20th Infantry Regiment, out of Joint Base Lewis-McChord. He graduated and was commissioned at the University of New Hampshire. He spent eight months as the battalion S-4, deploying his battalion to multiple training exercises including Orient Shield 2023 and the National Training Center.

--------------------

This article was published in the winter 2025 issue of Army Sustainment.

RELATED LINKS

The Current issue of Army Sustainment in pdf format

Current Army Sustainment Online Articles

Connect with Army Sustainment on LinkedIn

Connect with Army Sustainment on Facebook

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Social Sharing