"En algún lugar de la Mancha, de cuyo nombre no me acuerdo, vivió no hace mucho un hidalgo, de aquellos que tienen lanza y escudo antiguo en un anaquel y guardan un rocín flaco y un galgo de carreras" — Miguel Cervantes, “Don Quixote”

When I made the rank of “lieutenant colonel” at 13 years old, I was filled with the kind of naïve pride only a grandfather could instill in his eldest granddaughter. After all, it was my Abuelito Chapis who gave me this moniker, despite my age, my underdeveloped pre-frontal cortex, and some confusion as to whether he wanted me to serve the United States’ or Mexico’s Army.

But when I was 13 years old, none of that mattered: my abuelito, my hero and champion, affectionately called me “teniente coronel” every time we went to visit him at his house in Colonia Pedregal de San Francisco in Mexico City. I still remember the feeling of fulfillment that rested in my chest every time he greeted me with a small salute.

Jorge Velasco y Felix was a giant amongst men. A lifelong chilango from Colonia Tacubaya, Mexico City, my abuelito spent most of his childhood fighting poverty after his father passed away unexpectedly. Afternoons were spent alternating between homework, selling gum with his brother on the street to make ends meet, and escaping into hours of literary idealism with the likes of Don Quixote de la Mancha.

His natural intelligence coupled with innate determination put him through the Universidad Nacional Autonoma de Mexico, where he graduated with his law degree and top honors. However, Abuelito Chapis never forgot his first love and eventually left his law practice behind to pursue a career in literature.

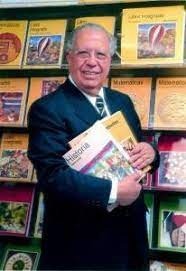

For 50 years, he led the life of a renowned publisher and editor in Mexico’s printing scene, spearheading initiatives that pushed for free access to books, magazines and newspapers around the country. He worked, and often fought, with national and community leaders to spread free literature into underserved neighborhoods and spent years going back and forth with stakeholders who didn’t see the value in his vision.

Abuelito Chapis could silence a room with one look behind his wire-framed spectacles, charm you with his inconspicuously-veneered grin and school you in a game of chess, all while dissecting the prose of Cervantes and Molina. He was a devout family man alongside his beloved wife Tere, and helped raise three incredible children: Jorge, Mayte and Enrique. The walls of his house were museums of his greatest achievements: photos of his six grandchildren, all proudly bearing his heritage from Mexico to the heart of Texas, all the way to the reefs of Australia.

For decades, my abuelito groveled about the state of Mexico, its politics and grieved that his “madre patria” had lost its way. But despite his relenting, my abuelito devoted his life to his country because serving the Mexican people was his calling. Every day, he climbed into his car — he never kept the same model for more than two years — and drove through the smog-covered streets of the city with the same determination that carried him as a child. He held on to his love for his country with the same iron grip as the eagle holding the serpent on the Mexican flag, and revered in his nation’s imperfections in the way only a true patriot could.

So, when Jorge Velasco y Felix lost his battle to lung cancer in 2014, years of cigar-fueled domino games coming to collect their debt, he left behind a legacy only the greats could write about. It’s that same legacy that has been my North Star, and the invisible guide that brought me to give back to my country as an Army Civilian a decade later.

Serving as the special assistant to the Assistant Secretary of the Army for Manpower and Reserve Affairs, I join the ranks of over 265,000 Army civilians who aim to leave our force more resilient, prepared, and welcoming every time we report to our duty stations.

As an Army Civilian, I have the honor of working with some of the best enlisted Soldiers, commissioned officers, and Department of the Army civilians to tell the Army story while also helping equip our more than 1 million Soldiers, civilians and their Families with the care they need to show up to the fight.

I have found myself falling in love with the people in this organization, folks from different backgrounds and walks of life who unite behind one mission and choose to serve and protect hundreds of millions of Americans they will never meet. It is an immense privilege to do this job, and I am proud to be a member of the Army Civilian Corps.

On days where the sun has long set on the Department of Defense and I am still sitting at my desk, facing the solemn 9/11 Memorial, I find myself thinking about my abuelito and how he must have felt during his toughest days at the office.

I grieve all the conversations we didn’t have and the lessons he could have taught me. I would give anything to hear him talk again about romanticism in literature — even though I still wouldn’t be able to understand half of it — and miss the way he always smelled like smoke and a cool Johny Walker on the rocks when he pulled me into a hug.

But grief is the highest form of love and it’s in these moments that I feel reenergized to continue serving in the way he did: selflessly and with the idealism of a Spanish knight on his odyssey through the arid lands of Madrid.

My first encounter with the United States Army came in the form of my high school’s JROTC program, one of the oldest and most prestigious in the state of Texas. In a battalion of more than 170 cadets, ranging from incoming sixth graders to outgoing high school seniors, the TMI Corps of Cadets felt more like a leadership crash course than an extracurricular activity.

From learning to about face without falling on to the cadet next to me to understanding why folding the flag inside out will get you demoted, my time in the corps molded me in ways I still think about today. When I became the first Latina battalion commander in the institution’s 121-year history, I was surprised, then chuffed, to learn I would be the only cadet to reach the rank of cadet lieutenant colonel. To this day, this moment in time fills me with gratitude for those who have never stopped walking by my side.

In more ways than one, I am constantly reminded that we are made of the legacies we carry.

Social Sharing