Throughout World War II, the leaders of the Allied forces discussed the possibilities of prosecuting Axis leaders for war crimes once the conflict ended. Because of the heinous actions of European Axis forces in their conduct of war, the Allies asserted the right to prosecute after the German surrender. The London Charter signed August 8, 1945, formed the International Military Tribunal, which initially charged twenty-four senior officials of Nazi Germany for conduct which violated the laws of war. While indicted, Gustav Krupp von Bohlen und Halbach was declared medically unfit to stand trial for his crimes, and Robert Ley committed suicide before the trial began.

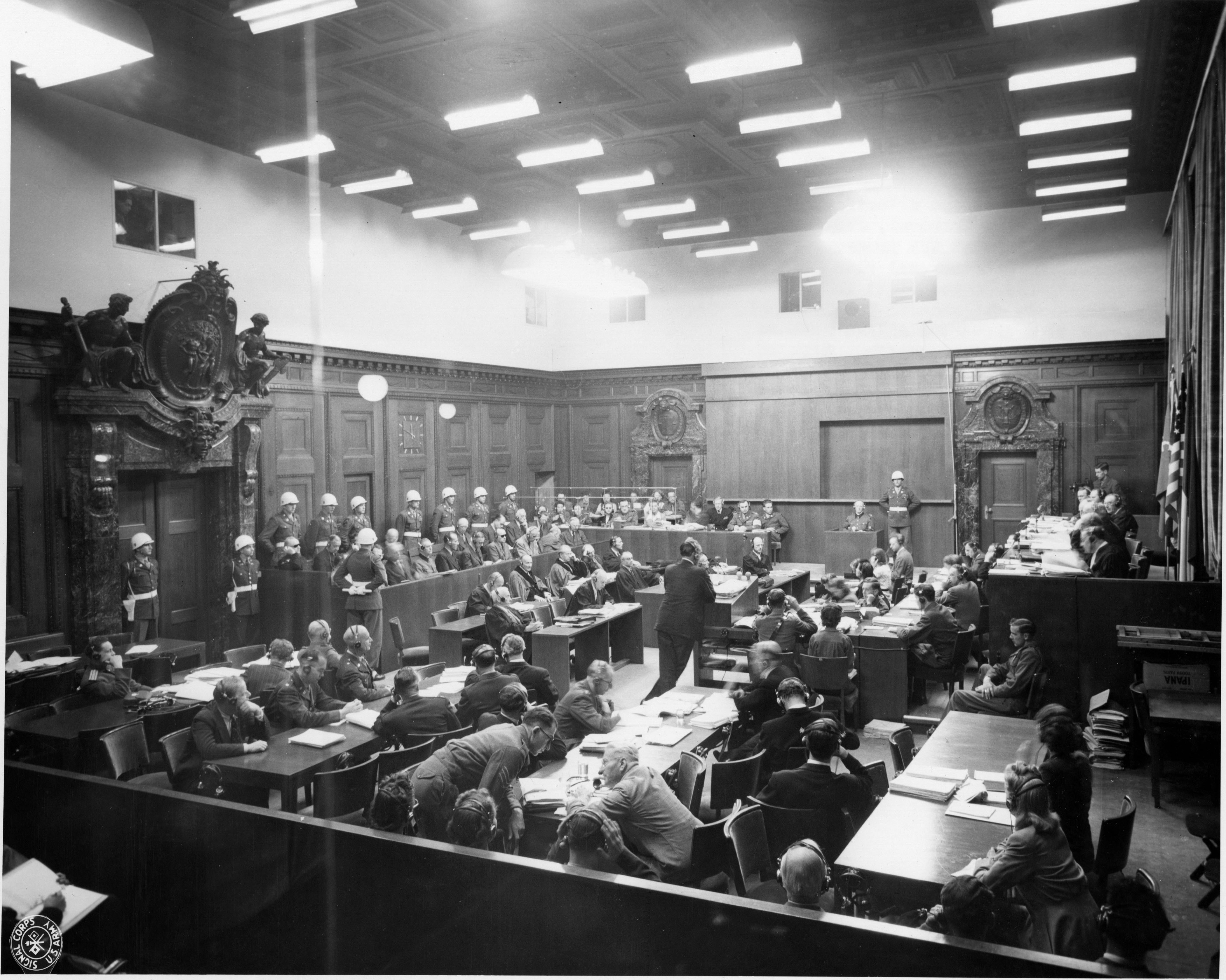

The first Nuremberg Trial was conducted from November 20, 1945, to October 1, 1946, when twelve senior leaders of the Nazi Regime were sentenced to "death by hanging" for their participation in war crimes. Two of the twelve sentences could not be carried out. Hermann Goering committed suicide the night before his scheduled execution, and Martin Bormann had been tried in

absentia. The remaining ten war criminals were executed October 16, 1946.

Whereas much has been written about the trials and the men on trial, not that much has been written about the 6850th Internal Security Detachment and its commander, who were responsible for the security of the Palace of Justice, where the trials were held, and of the prison within its walls. Colonel Burton C. Andrus was initially assigned by the Supreme Allied Commander, General Dwight D. Eisenhower, in May 1945 as commandant of a secret interrogation center in Mondorf-les-Bains, Luxembourg. Code-named "Ashcan," the interrogation center was located in the former Palace Hotel (well on its way to being stripped of its luxurious amenities when Andrus arrived). One by one, the captured senior officials of Nazi Germany arrived at the interrogation center.

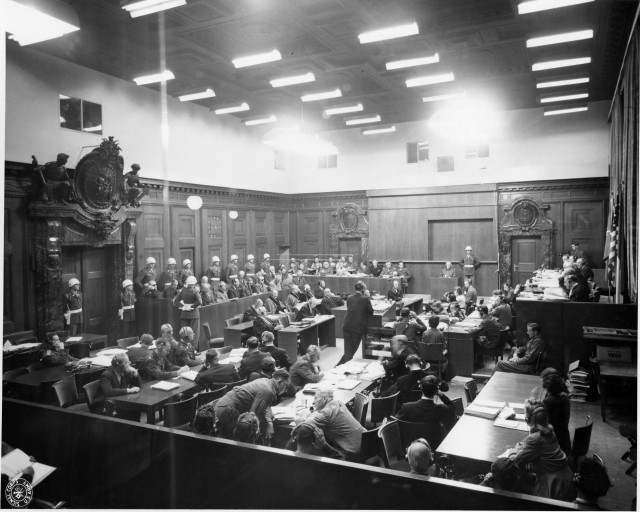

Over protests from the Soviet Union, which wanted the trials to take place in Berlin, the Palace of Justice in Nuremburg was chosen for two main reasons: the building remained intact despite severe Allied bombing throughout Germany, and Nuremburg was previously the location of many propaganda rallies of the Nazi Party. On August 12, 1945, Andrus moved his notorious prisoners by airplane to Nuremburg.

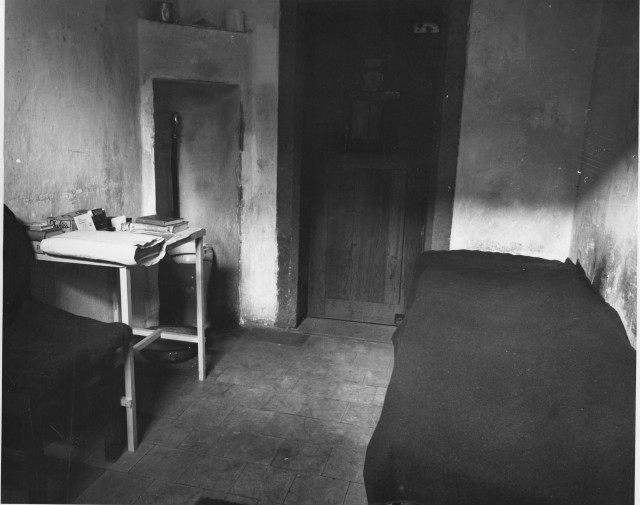

To outsiders the choice of Andrus, a cavalry officer by branch assignment, to be a prison commandant might have seemed odd, but he did have some experience in prison and security work. Early in his thirty-five year Army career, Andrus served as a prison officer at Fort Oglethorpe, Georgia. For two years during the early part of World War II, he served in various security and intelligence positions around New York City, which included security for the New York Port of Embarkation. Drawing on his earlier experience at Oglethorpe, Andrus went about establishing a rigorous security protocol for the prison. After Ley committed suicide on October 25, 1945, the security protocol was made even stricter. Each prisoner was now assigned a guard facing the cell door, so they were under constant observation.

Despite the fact that the spotlight of the world was on the mission of the 6850th Internal Security Detachment, the work of prison security was often thankless. The strain of the constant supervision of high-profile prisoners (who were often quite obstinate), strenuous duty hours (twenty-four hours on duty, twenty-four hours off), and the high turnover rate of personnel (which Andrus estimated to be over 600%) made the job that much more tedious. Throughout it all, Andrus demanded that the prisoners be treated with human dignity despite the actions for which they had been charged. In one incident, Private First Class Joseph Traina was forced to use a blackjack (the only weapon personnel of the 6850th were armed with inside the prison walls) on Goering when the German general attacked him, but throughout the event Traina maintained his military discipline, using only the amount of force necessary to subdue Goering.

On October 16, 1945, Andrus escorted the ten condemned men to the gallows. It was not something that he took pleasure in; he was doing his duty like other United States soldiers before him and since. The United States Army Military History Institute is honored to maintain and make available for research the personal papers of Colonel Burton C. Andrus in its collections.

ABOUT THIS STORY: Many of the sources presented in this article are among 400,000 books, 1.7 million photos and 12.5 million manuscripts available for study through the U.S. Army Military History Institute (MHI). The artifacts shown are among nearly 50,000 items of the Army Heritage Museum (AHM) collections. MHI and AHM are part of the: Army Heritage and Education Center, 950 Soldiers Drive, Carlisle, PA, 17013-5021.

Related Links:

A Working Bibliography of MHI Sources: Andrus, Burton C. Collection

Social Sharing