Today, most people look at their phones to see what the weather will be. That ability relies on more than 150 years of Signal Corps research and development. A major breakthrough in forecasting was the development of satellite monitoring. Television and Infra Red Observation Satellite was launched on 1 April 1960 by an Air Force vehicle, to televise cloud formations within a belt several thousand miles wide around the earth and transmit a series of pictures back to special ground stations. This first television-type satellite for world-wide cloud cover mapping was produced under Signal Corps technical supervision and NASA sponsorship. Its two TV cameras -- one a wide-angle lens photographing 800-mile squares of the earth's surface and the other shooting 30-mile squares, ranging between the latitudes of Montreal and New Zealand, were of different resolution for direct readout and tape storage. This represented the most intricate control so far used in a satellite.

The first orbit pictures were rushed to Washington on a new facsimile machine, also developed by the Signal Corps Research and Development Laboratory. It transmitted a high-quality picture to its destination in just four minutes. As a result, the first pictures from TIROS were on the President's desk shortly after they were received from the satellite, and he personally released the information to the world. During its three months of operation, TIROS sent down more than 22,952 pictures of cloud formations, depicting the world as man had never seen it. Although it was only an experimental forerunner, TIROS I made some important discoveries and contributions to meteorological research.

The use of satellite technology for forecasting reflected almost a century of Signal Corps interest in meteorology and weather prediction. After the 9 February 1870 law directing the War Department to take meteorological observations and share them around the country using telegraph, the Chief Signal Officer was assigned the responsibility on 15 March 1870. Eventually establishing daily weather maps for the nation, and publishing the Daily Weather Bulletin, Weekly Weather Chronical, and the Monthly Weather Review, the Signal Corps created a means for conveying important information for agriculture and industry around the county. This led to a major telegraph-line construction effort by the Signal Corps beginning in 1873. The Signal Corps would continue these duties for 20 years, until the establishment of the National Weather Bureau under the Department of Agriculture in 1890.

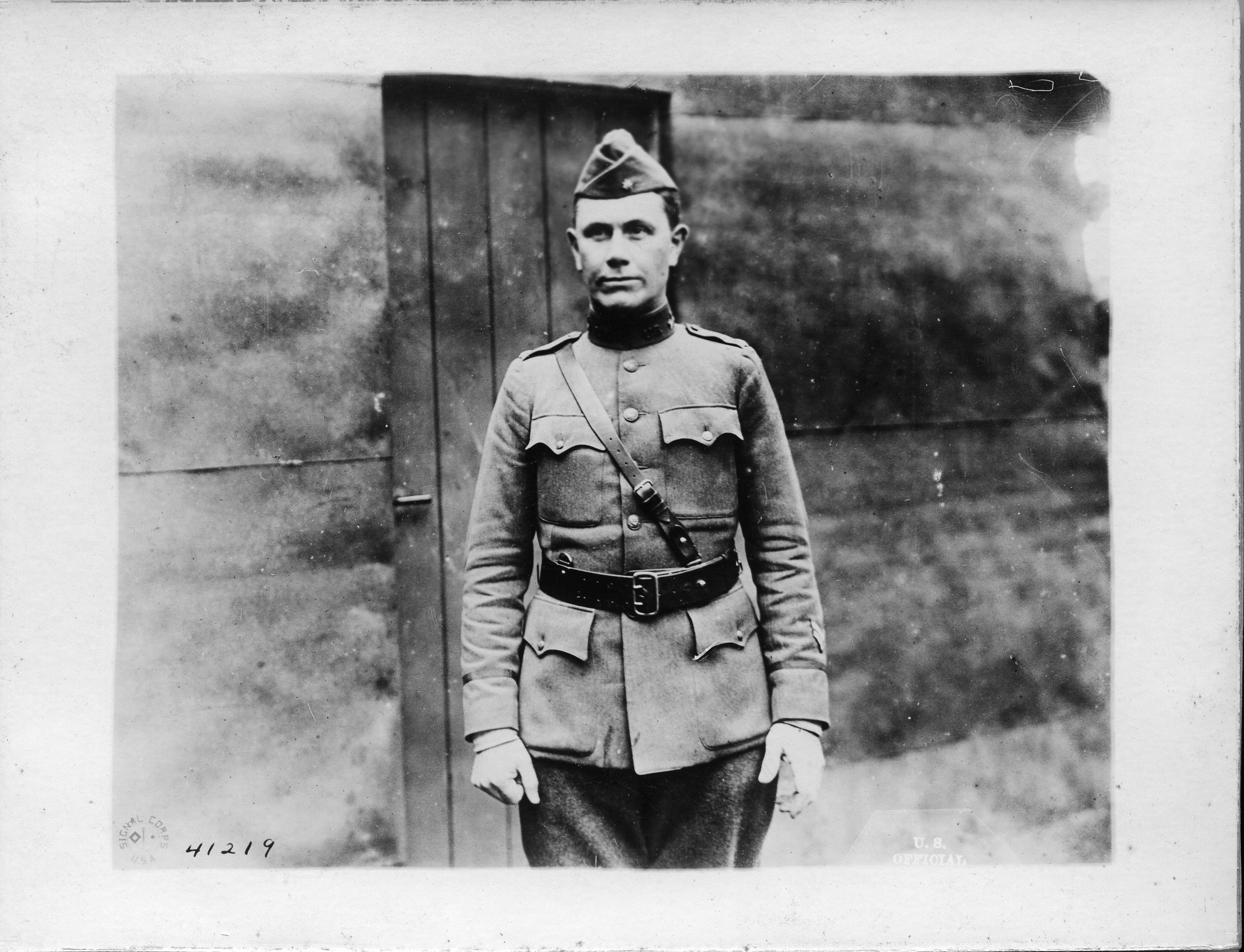

World War I brought a resurgence of interest and responsibility for meteorology to the Signal Corps, and a Meteorological Section was established in 1917. Commanders needed the information to support anti-aircraft and long-range artillery, aviation, sound ranging to detect enemy artillery, and general operational planning. The use of gas warfare also required knowledge of wind currents and velocity. The Signal Corps had to recruit experts from outside the Army to meet their needs, and one individual, William R. Blair, received a commission as a major in the Signal Corps’ Officers Reserve Corps and became the chief of the Meteorological Service in the American Expeditionary Forces. Blair was appointed as the director of the laboratories at Fort Monmouth in 1930 and drew on his background in meteorological forecasting and experimenting in sound ranging to help develop the pulse-echo method of location, becoming the “Father of Army Radar.”

The Signal Corps’ interest in meteorological programs would continue to support Army aviation program and communications, conducting research in the Meteorological Division of the laboratories at Fort Monmouth throughout the mid-Twentieth Century. Project Cirrus worked at controlling the weather with cloud-seeding experiments, and the labs were using radar to track storms in the 1940s. The Signal Corps also developed an electronic computer that would determine high-altitude weather conditions and perform the calculations necessary for a forecast. The Signal Corps also conducted climatological studies around the world, including research teams in Antarctica and the North Pole. The next time you know to bring an umbrella, think of the years of Signal Corps research behind the forecast.

Social Sharing