To say that Debbie Brewer has learned her role as a wildlife biologist at Fort Huachuca from the ground up and from all sides is a pretty good description of her career path.

With a four-year stint as the Integrated Training Area Management program manager for the Arizona Army National Guard and the extensive land management duties that entails, as well as a six-year tenure as a contractor conducting sensitive species monitoring on Fort Huachuca, Brewer truly has engaged on multiple fronts with Army natural resources issues. Now, in her twelfth year as a wildlife biologist managing sensitive species and their habitat to support the training mission, Brewer brings a wealth of experience to her work, and she’s very clear on what that takes.

“I manage the natural resources to protect the mission,” she said. “We balance training with the conservation of natural resources, ensuring that the mission moves forward while sensitive species and their habitat can be protected in perpetuity. We strive to do that and I think that, to a large extent, the cooperation with our division and training does that. We get the mission completed, and though we may have to make changes to some degree, we get it done.”

Calling the Arizona-based Fort Huachuca “a fantastic location” with more than a dozen defined vegetation types from grasslands to mountain forests just 15 miles north of the Mexican border, Brewer describes the setting as a range of high-desert landscapes and semi-arid grasslands “on to the sky islands” of the Huachuca Mountains.

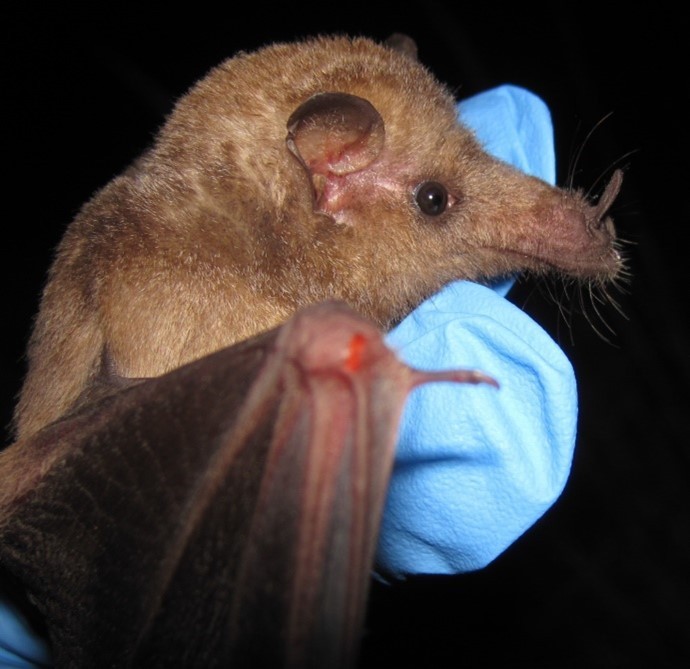

“We have high species diversity here, due to the varied topography and close proximity to Mexico, with a lot of sensitive species and habitat, including the nectar-feeding lesser long-nosed bat, Mexican spotted owl and rare ocelot and jaguar detections,” she said, adding that in all there are nine threatened and endangered species found at the installation. Grassland conservation, high elevation fuels and invasive species management, and native species conservation factor into the work of her team and the entire installation.

Helping to protect these plant and animal species requires regular communications with natural resource and ITAM colleagues, as well as with the state and federal regulatory agencies. This collaboration is something Brewer said is critical for her and her team.

“Collaboration has always been important,” she said. “In today’s times, we’re managing against effects that are occurring not just on the installation, but regionally and nationwide. Those collaborations are imperative. Through those communications, we are able to develop a solution that generally meets all the goals.”

Brewer did say that one land management technique that has paid dividends at other installations in a different climate and time – the use of controlled burns – does not translate well in today’s environment due to the widespread nature of invasive grasses.

“When we put a fire on the ground, what’s been coming in are invasive grasses rather than a return of the natives,” she said. “The invasive species are just more resilient than the native grasses, which require two to three years to come back. It’s a conundrum. We want to put fire on the ground because it is an important environmental regulator, but when we put it on the ground, we lose our native grasses and increase the future fuel load and fire hazard.”

“That requires different strategies,” she said. “We’ve been thinning in the high elevation to reduce the fuel load and reduce resource drain allowing trees to get bigger. We also do our best to reduce the fuel load in the grassland by managing against invasive grasses. Both are important to help protect from catastrophic wildfire.”

Brewer also said that using the skills and experiences of the natural resource professionals at the installation is a critical part of managing in such a complex natural environment.

“We’re constantly having to find ways to do things faster and smarter. New technological tools have greatly enhanced our toolbox, but it is imperative to still have biologists on the landscape,” she said. “We are now able to use genetics to identify both individual and environmental conditions more accurately, to see what species are or were in an area, Using technology to enhance our work is imperative.”

Social Sharing