Chief Warrant Officer 5 Chris Westbrook enlisted in the Army in 1996 as a switchboard operator, holding the rank of private first class. Prior to joining, Westbrook said he was running himself “ragged” working one full-time and three part-time jobs. Like many others who join, Westbrook viewed the Army as an opportunity to establish financial stability and a better life. He had no idea at the time how much of his life would change as a result of that decision and one fateful day.

Westbrook, U.S. Army Signal Regiment chief warrant officer and senior technical advisor, was on Day 2 of a training exercise at Fort Stewart, Georgia, on Sept. 11, 2001. His team started around 5 a.m. that morning, and a few hours later, Westbrook went home for breakfast with plans to return then pick up where he left off. During his drive home, Westbrook heard news on the radio of a plane crash, but didn’t think much of it at the time.

“As I was halfway through breakfast, the second plane hit, so I grabbed it ‘to go,’ I went back, and it was chaos, because by then the news had broken out,” Westbrook said.

A chaotic scene awaited him at Fort Stewart as security measures immediately increased and Soldiers tried to access the installation while news of the unfolding events began to unfold. What was supposed to be a weeklong training event ended abruptly and Soldiers were told to “stand by” as they awaited further instruction. Some wound up packing and putting their training into action on deployments in the days that followed, while others, including Westbrook, moved elsewhere; in his case, to Korea for a year. It wasn’t January 2004, after attending Warrant Officer Candidate School, Westbrook made his way to Iraq.

“That was not what I was ready for,” Westbrook recalled. “Aside from the weather, the climate … the other thing you realize is when mortars start coming in three times a day, three to four days a week, this is real. You start getting introspective, think a little bit more about your own protection and protection of your fellow Soldiers.”

He was there for the First Battle of Fallujah, also known as Operation Vigilant Resolve, and spent time in Ramadi.

“It was pretty scary,” Westbrook said. “Ramadi was not a peaceful place by any stretch of the imagination, and it did not get any better.”

Although relieved to be going home after seven months, returning to the states presented its own challenges.

“The Army had yet to come up with a methodology to deal with traumatic stress,” Westbrook said. “We had some plans in place, but like everybody else, we learn.”

In many ways, that deployment changed Westbrook’s thinking, who initially planned on fulfilling his original contract then returning to the civilian sector. Instead, he chose to stay in.

“At that point in time, there was a sense of purpose,” Westbrook said. “We were always looking forward to the next deployment, because we knew this was going to be a cyclic thing.”

Westbrook deployed to Iraq again in 2007, this time for 16 months. In some respects, the second go-round was easier.

“I knew going in what I was getting into,” Westbrook said.

But the extended time away from family made it increasingly difficult. Fortunately, there were more resources readily available to deployed service members compared to his first deployment – resources including mental health professionals, fortified living quarters, recreation, and “more mandates by commanders saying, ‘Yes, we’re here 24/7, but you have to take some time off,’” Westbrook said. “There were more coping mechanisms than just going back into your room and avoiding things.”

Looking back on his military service, which includes a Bosnia deployment and third deployment to Iraq, Westbrook said he would do it all over again even if he knew 9/11 was going to happen.

“That day kind of solidified it a little bit more,” Westbrook said. “The bond I had with my teammates … even though I did not deploy with that team, from then on out, that was the main focus – making sure that they’re the best trained and that they were ready to go when we did deploy.”

Similar to Westbrook, Chaplain (Maj.) Robert Cox gained newfound purpose in the midst of tragedy. Cox, Signal Regiment chaplain and ethics instructor, joined the Army several years later in 2009, at the height of the surge. Cox was working as a pastor at the time when his friend, a Navy chaplain, told Cox that the Army was “desperate for chaplains.”

“He said, ‘It fits what you want to do – you want to work with young people, do outreach,’ and the irony is that I had been at ROTC at Florida State in an undergraduate program, and I didn’t take a commission at that point … but I never thought about being a chaplain. I don’t think I even knew that chaplains existed at that point,” Cox explained.

A short time later, Cox deployed to Afghanistan – first in 2010, then in 2014.

Reflecting on the 9/11 and events that followed, Cox said that despite being one of the world’s most horrific attacks, the terrorists who committed the act did not fully succeed.

“They were trying to show the world that the United States was less than what it appeared to be, and I think what they showed is that we’re actually more than we appeared to be,” Cox said. “They forced us to think about who we are, and I think we came up with a better answer than they thought we would … we are resilient, adaptive, able to overcome … and the U.S. Constitution is worth defending.”

Getting help

Even after 21 years, the effects of 9/11 are real and not to be taken lightly.

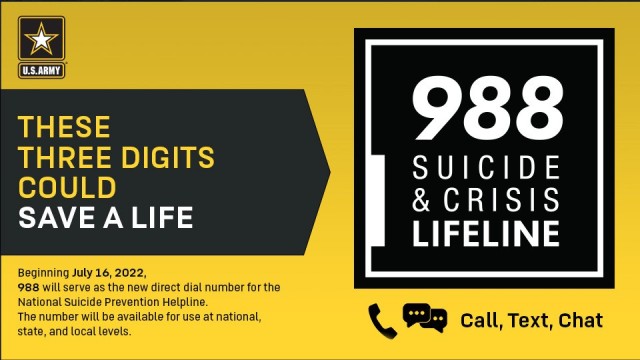

If you are a service member who suffers from post-traumatic stress, moral injury, or simply need someone to talk to, reach out to your unit’s chaplain or behavioral health team. Anyone else may wish to contact call or text 988. There are also resources available from Military OneSource at www.militaryonesource.mil.

Social Sharing