FORT HAMILTON, N.Y. – Fort Hamilton honored the life and sacrifice of a Brooklyn native, Vietnam War veteran, and Medal of Honor recipient, during a street renaming ceremony, May 20.

The ceremony officially removed Confederate Civil War General Robert E. Lee’s name from the main avenue and renamed it John Warren Avenue in honor of U.S. Army 1st Lt. John E. Warren, Jr.

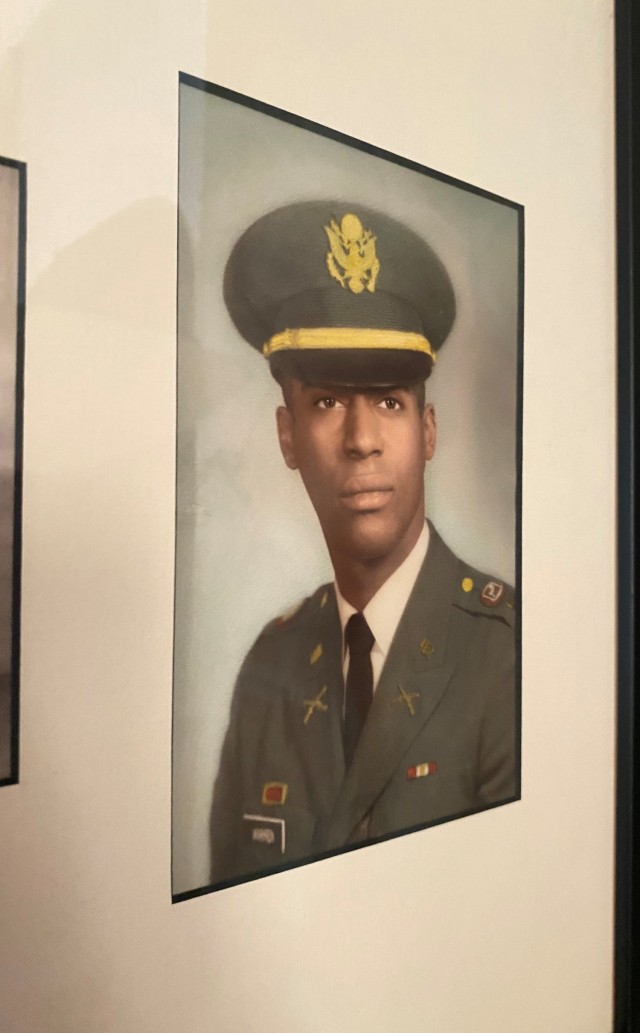

Warren was 22 years old and served as a platoon leader in Vietnam when he used his body to shield three fellow Soldiers in his platoon from a thrown enemy grenade; he gave the ultimate sacrifice and perished January 14, 1969 in Vietnam. He was posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor, the nation’s highest award for valor, and was the recipient of the Silver Star, Bronze Star, and Purple Heart.

“Since I’ve been here [July 2020] this is something that we wanted to accomplish,” said Col. Craig Martin, Fort Hamilton Garrison Commander, in his opening remarks. “Today is a joyous day. It is a time for change. If we want to be leaders in the Army and say that we are people first and that we want to make a difference, we have to take action. We have to make a difference, and we are. Our Army is an institution that embraces diversity and inclusion and rejects hate and prejudice. Fort Hamilton is our home and our community. This street links this community together and it’s the backbone of Fort Hamilton; that backbone should be named after someone worthy of all we are as a diverse New York City population.”

The garrison had been working on changing the main street’s name for over two years and prior to the announcement of the William "Mac" Thornberry National Defense Authorization Act for 2021, passed by Congress in 2020. The Authorization Act mandates the removal and renaming of Department of Defense items that commemorate or are named after any person that voluntarily served with the Confederate States of America within three years and tasks the Naming Commission with developing a plan to carry it out.

In addition, through the Army’s Memorial Program, memorializations must honor deceased heroes and other deceased distinguished individuals of all races in society, and will present them as inspirations to fellow Soldiers, employees, and other citizens. Specifically, for a street renaming, the individual memorialized must be deceased distinguished individuals and Medal of Honor recipients.

Typically, the Installation Management Command commander approves names for buildings, areas, and streets on most Army installations and may delegate the responsibility to an installation’s senior commander, but to support the DOD Naming Commission mission, the Assistant Secretary of the Army - Manpower & Reserve Affairs established a moratorium on April 19, 2021 on all naming actions concerning the Confederacy. Commands may submit Exception to Policy package requests to the ASA(M&RA) for approval to rename items related to the Confederacy. This process enables the Army to keep the Naming Commission apprised of changes.

"This team cared, wanted to make a difference, and we persevered,” said Martin regarding the lengthy approval process. “We got a number of signatures, put together packets, requests, and justifications. We began with a board that assessed who we could name this street after.”

Martin stood up a committee to identify the best candidate to memorialize. The board was comprised of representatives from the garrison and mission partners, to include the NYC Recruiting Battalion, 1179th Transportation Group, NY Military Entrance Processing Station, Directorate of Public Works, Installation Safety Office, Harbor Defense Museum, and the Public Affairs Office. The committee chose 1st Lt. Warren amongst six other finalists based on the following criteria: Vietnam War era veteran; a Brooklyn native; community representative with local ties to their community; and must fall into the category of underrepresented population/ethnic group.

Fort Hamilton’s request package was then prepared and submitted up the chain of command, making its way to the Pentagon and onto the desk of Yvette Bourcicot, Acting Assistant Secretary of the Army (Manpower and Reserve Affairs), for final approval. She also served as a guest speaker for the ceremony.

“I saw this one [request package], and I said, ‘I would love to sign this,’” said Bourcicot during the ceremony. “I felt moved to come here, because it was so meaningful to me. This is one of the most thrilling things I’ve been able to do in my tenure, and it’s an honor and privilege to be here.”

Bourcicot described Warren as an ordinary man with extraordinary bravery and love: love for his family, love for his brothers-in-arms, and his resounding love for his country. She said it’s a story the Army is proud to tell.

“John Warren Avenue will continue to embody his memory and bear witness to his legacy – a legacy of service, bravery, and heroism,” added Bourcicot.

She also highlighted the new street sign’s location, which is in front of the New York Military Entrance Processing Station, the second largest MEPS in the United States and the gateway through which applicants enter the armed service.

“I think it’s fitting to have his memorial near a MEPS for new recruits,” said Bourcicot. “Today, in our all-volunteer Army, young men and women choose to serve. From Brooklyn, New York to Atlanta Georgia to Seattle, Washington and every corner of our nation — new Soldiers of all backgrounds raise their right hand and swear to support and defend our constitution and nation. I hope those who enter here understand, as John Warren did, that they are being called to stand and serve our nation, something bigger than themselves. I also hope these new Soldiers understand the significance of where their own Army stories will begin”

Steve Castleton, Civilian Aide to the Secretary of the Army and a guest speaker, provided remarks on the sacrifices that military members and their families endure, and how heroes are found within the local community."

“Ordinary men and women who did extraordinary things to spread the freedoms that we often take for granted…where do we find such heroes?” asked Castleton. “We find them where we always find them: in our villages, towns, city streets, shops, farms, and the streets of Crown Heights.”

Warren’s only surviving immediate family member, Gloria Warren-Baskin, 70, commented on how she first found out that her brother was considered as a candidate to be memorialized.

“I’m proud to be here today,” said Warren-Baskin. “When I first learned about this in 2019, I was very ecstatic, but I never told my family about it; they didn’t know anything about it until a couple of months ago. I did not tell anybody because I did not want them to get excited. When I was told about it, they [Fort Hamilton] said it was a consideration. Then in 2021, I was contacted and told it was going happen, so now I could tell somebody.”

Warren-Baskin said that on April 15, 1969, her family was at Fort Hamilton to receive the Silver Star Medal, Bronze Star Medal, and the Purple Heart on behalf of her brother. In 1970, she and her family accepted the Medal of Honor from President Richard Nixon at the White House; in 1988, an arts and crafts building on Schofield Barracks Army Base, Hawaii was named after John; and in 2016 she visited the National Museum of African American History that had a plaque with her brother’s name on it.

“In 2022, a street sign is being renamed after him,” she added. “This is a big deal because my brother was born and raised in Brooklyn and attended the public schools in Brooklyn. It is an honor to have a street sign here at Fort Hamilton with his name on it in Brooklyn, his home.”

She continues, “When Army personnel, their family members, and retirees walk along John Warren Avenue, they may ask themselves, ‘Who is John Warren?’ I hope they would take the time to look his name up, and know he is deserving of this honor. He [John] would want people to know that he was proud to be a Soldier in the U.S. Army, and we should not be afraid to help our fellow man. It feels good to know that after all these years, 53 years to be exact, that he is still recognized for his bravery. My family and I are proud of him, and in my family, he is our hero.”

James Hendon, NYC Department of Veterans’ Services commissioner, was the final guest speaker and reflected on what we lost with Warren’s ultimate sacrifice.

“At the time of his death, he was 22 years, one month, and 29 days old,” said Hendon. “The median age of those who died in Vietnam was 23.1 years old. Had he lived beyond the war and beyond that fateful day in time and province, statistically speaking, John would have lived another 50 years to age to the age of 72.7. He had greater than six percent likelihood to be married, and he would have had two children and four grandchildren.”

Hendon continued that Warren, had he lived, would likely have owned a home, a business, volunteered in the community, attend public meetings, solve community problems, and continued to lead.

“When you think of all that was left behind, when you think of the dream deferred, I ask of you to think of all the 58,220 souls of U.S. patriots who died in Vietnam,” said Hendon. “When you look beyond Fort Hamilton and beyond NYC, we do not have many bases with major streets named after our Vietnam veterans…Actions like what we are doing today, make sure that the 2.7 million men and women who served, and all those who died, and those who are still missing, and those who have died from complications afterwards from the War, that those people are not forgotten.”

Hendon continues, “Decisions like John made while patrolling through the rubber plantation with his platoon…were pure, swift, and selfless. They were not layered with hesitancy, they were not layered with materialism, they were not layered with his desire for placing his needs above others, nor were they layered with over interpretation… It takes a time delay, fragmentation, anti-personnel grenade two to six seconds, from when the safety pin is removed to when it explodes. In those two to six seconds, one has to assume that John wasn’t thinking about race when he jumped on that grenade. He wasn’t thinking about gender, class, religion, creed, politics, or the Civil War. He was just thinking, ‘I need to save these people’s lives.’ He could have chosen to save himself. He could have chosen to live the life I told you he would have lived had he made it home… I want to make sure we recognize the purity of his heart in his own decision.”

Hendon concluded the ceremony with three final thoughts.

“One, use this renaming to reflect on all that we lost through those men and women who made the ultimate sacrifice for this nation in Vietnam. Two, let John’s sacrifice be a lesson that doing the right thing, the selfless thing, often has a heavy cost but the decision itself is pure, it is clear, and it is colorblind. It is the right thing to do; it’s not complicated. Three, given everything that we’ve seen today, and with our men and women who served this nation throughout time, always ask yourself, ‘What am I doing to earn this?’”

Social Sharing