Operation Flintlock (Jan. 31 - Feb. 4, 1944) marked the initial phase of the American invasion of the Marshall Islands in the Central Pacific during World War II, resulting in the US forces’ seizure of Kwajalein Atoll and Majuro, giving the Americans a foothold in the crucial island chain.

Few military organizations trained and fought in a wider range of environments than did the Soldiers of the 7th Infantry Division in World War II. Activated in 1940 at Fort Ord, California as a motorized infantry division, the men of the 7th prepared for deployment to North Africa and by training in the deserts of California and Arizona. Rapidly evolving world events, however, saw the Bayonet Division receiving orders west instead of east. Following amphibious warfare training on the California coast with the US Marines, the Division sailed north to the Aleutian Islands. Ill-trained and ill-equipped for arctic warfare, the Bayonet Division nonetheless prevailed over both the Japanese defenders and the elements and successfully wrested the islands of Attu and Kiska from the Japanese.

From the frigid waters of the Bering Sea, the Division moved to Hawaii where it joined with the 4th Marine Division to form the Fifth (V) Amphibious Corps, known as “VAC”. By the time the 7th Division had joined VAC in Hawaii, American Pacific strategy established a two-prong attack toward the Japanese home islands. General Douglas McArthur’s Southwest Pacific Area (SWPA) forces would advance north from New Guinea towards the Philippines while Admiral Chester Nimitz’s forces advanced west across through across the Central Pacific Area. In November 1943 Nimitz’s joint force of Army, Army Air Force, Navy, and Marines seized the Gilbert Islands to protect the southern flank of the central Pacific thrust through the Japanese Mandate islands groups of the Marshalls, Palau’s, and Marianas.

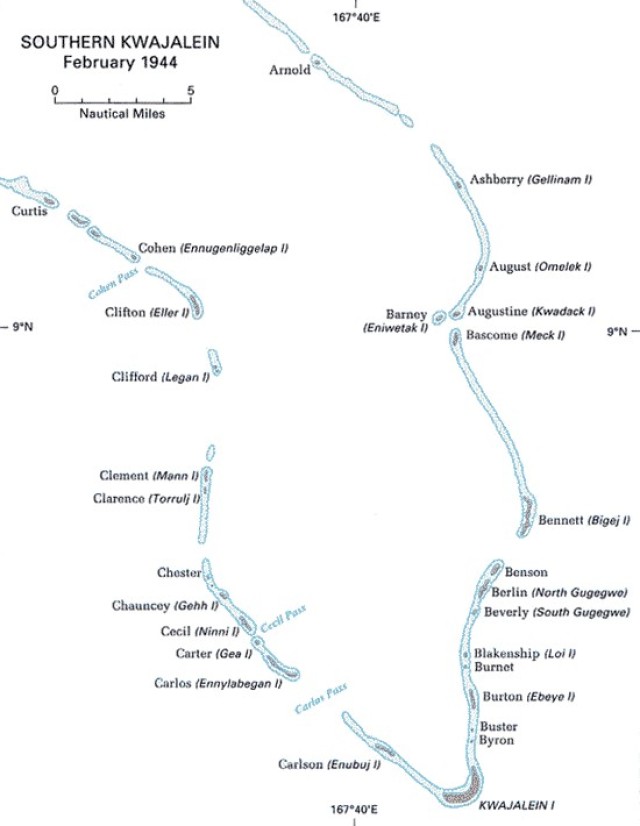

First in line was the Kwajalein atoll, the largest coral atoll in the world. Consisting of 94 islands and islets, over a third of which large enough for military use, the atoll had been part of the Japanese “mandate” islands ceded to Japan by the League of Nations after World War One. The 7th Division was tasked to take the island of Kwajalein in the southern flank of the atoll while the 4th Marine Division seized the northern flank main islands of Roi and Namur.

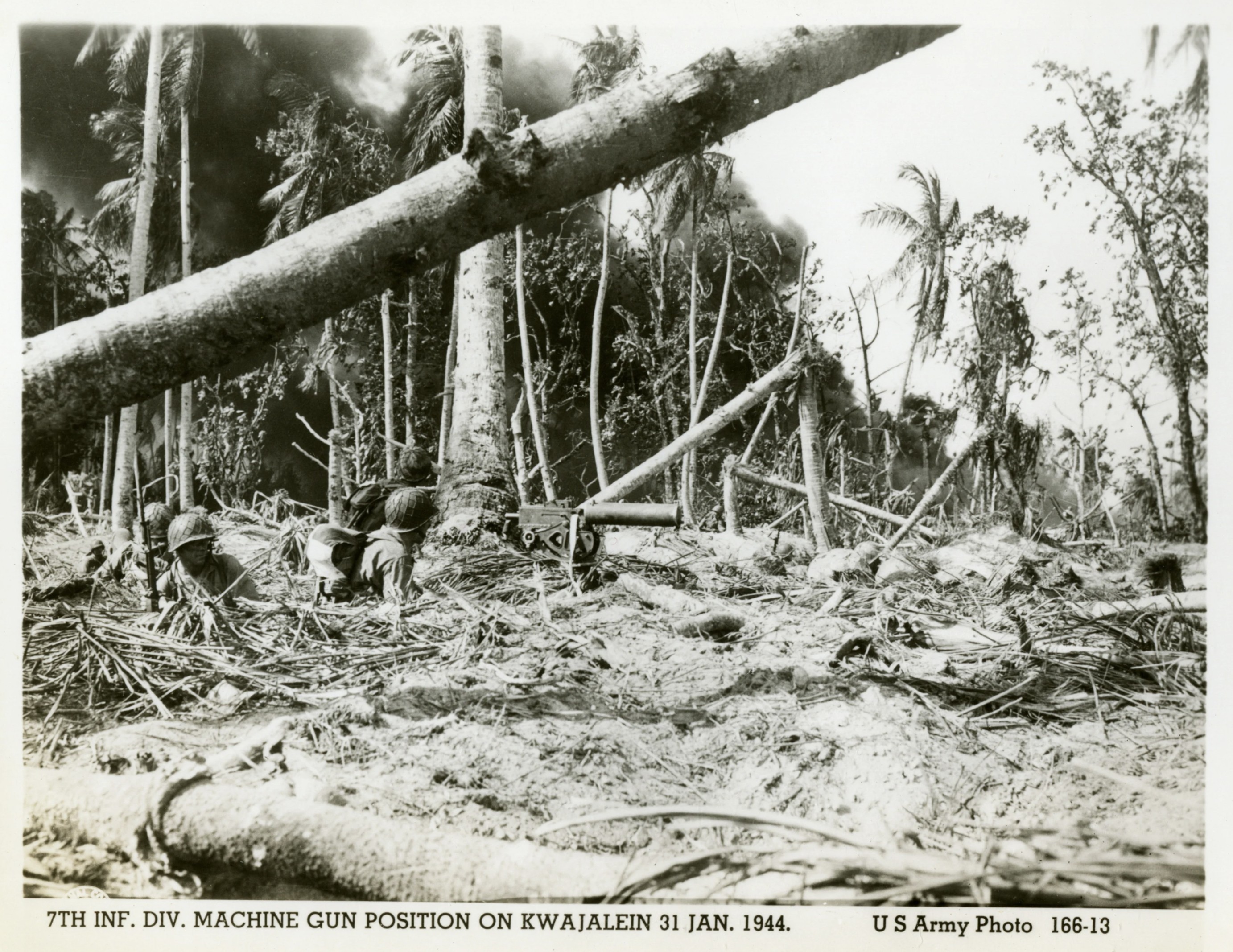

The 7th Division’s 17th Regiment Combat Team (RCT) was tasked to seize a grouping of small islands to northwest of Kwajalein in order to secure the Carlos Pass, the primary entrance into the atoll’s inner lagoon. Possession of these islands also allowed the establishment of artillery positions from which the main objective of Kwajalein could be bombarded. The Division’s 7th Cavalry Troop augmented by two companies from the 111th Infantry Regiment, were tasked with seizing these smaller islands, codenamed “Chauncey”, “Cecil”, “Carter”, and “Carlos”. On D-Day, January 31st, the cavalry troop led the dawn assault, conducting landings via rubber boats followed by the 111th Infantry troops in landing craft. A series of short, sharp engagements followed subduing the contingents of Japanese defenders.

At 0930 on the morning of February 1st, under 7th Division artillery cover from “Carlos”, the Bayonet Division’s 32nd and 184th Regimental Combat Teams landed battalions in column on the western end of Kwajalein; the 184th RCT on the northern Red Beach 1, and the 32nd RCT to the south on Red Beach 2. Only 2.5 miles long and less than 900 meters wide, Kwajalein’s geography and topography precluded a conventional defense-in-depth. As a result, beach defense combined with counterattacks surfaced as the only viable defensive option for the Japanese. Enemy resistance at the shoreline, though vigorous, was rapidly overcome with both 7th Division assault elements half-way across the island’s airfield by nightfall on D+1. The offensive drive continued at daylight the following day with the 184th RCT pushing along the northern coast and the 32nd PRCT advancing along the southern coast. The 184th advanced to a point short of the island’s northern tip, ceding the remainder of the island to the more experienced 32nd RCT. Despite the relatively rapid advances of D+1, operations on D+2 and D+3 (2-3 February) were plagued by confusion and slow movement caused by pockets of bypassed Japanese defenders. Hard fighting continued until the evening of D+4 when Major General Corlett, 7th Division commanding general, declared Kwajalein secure.

With the Marshalls under US control, the Southern flank of the Central Pacific Area was secured and the path to the Marianas, whose islands placed US bombers within striking distance of the Japanese home islands, was open. Seven months after operation Flintlock the bombers that dropped the atomic bomb on Hiroshima and Nagasaki were launched from the Mariana Island of Tinian bringing the Second World War to an end.

____

Erik W. Flint is a Lt. Col. in the US Army Reserves and serves as the I Corps command historian. He conducts his work out of the Lewis Army Museum located in the Historic Red Shield Inn building on Joint Base Lewis-McChord (JBLM). The Lewis Army Museum is the only certified U.S. Army Museum on the West Coast. For more information, visit https://lewisarmymuseum.com.

Social Sharing