Officials advise protecting self before being bit, getting tested afterward

FORT KNOX, Ky. — When Renee Rhodes arrived to her new job at Fort Knox in 2012, she had big plans and a ton of energy devoted to becoming the best photographer around — a fresh start to a new life.

In mid-May, however, sickness had set in and begun hampering her efforts.

“I honestly thought it was because I was fatigued because I had taken on the new job, I was going through a divorce, and I had two small kids,” said Rhodes. “A lot of things were changing.”

She quickly discarded the idea that she was suffering from influenza or strep because of the time of year. Those illnesses typically didn’t manifest in May.

“I kept getting sicker and sicker,” said Rhodes. “My brother made a comment to me in passing one day because I was falling asleep while he was talking to me.”

Her brother asked what was wrong. Rhodes told him she was just tired all the time. He questioned her about her exhaustion and then made an observation that would eventually send her on an unexpected path that she remains on to this day.

“He said to me, ‘You’re kind of acting like a friend of mine Eric was; he has Lyme disease,’” recalled Rhodes. “I laughed and said, ‘I do not have Lyme disease because Lyme disease is very well known for giving you a bullseye marking.’”

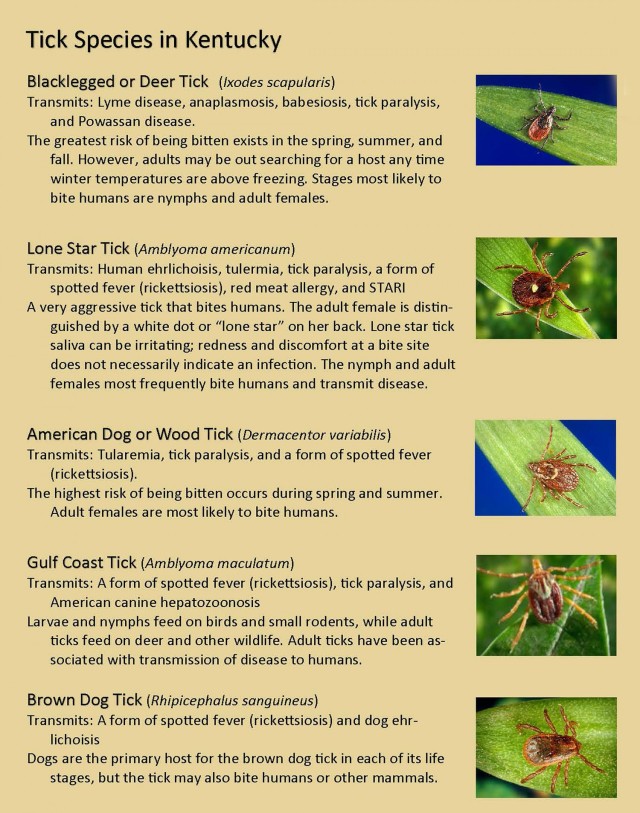

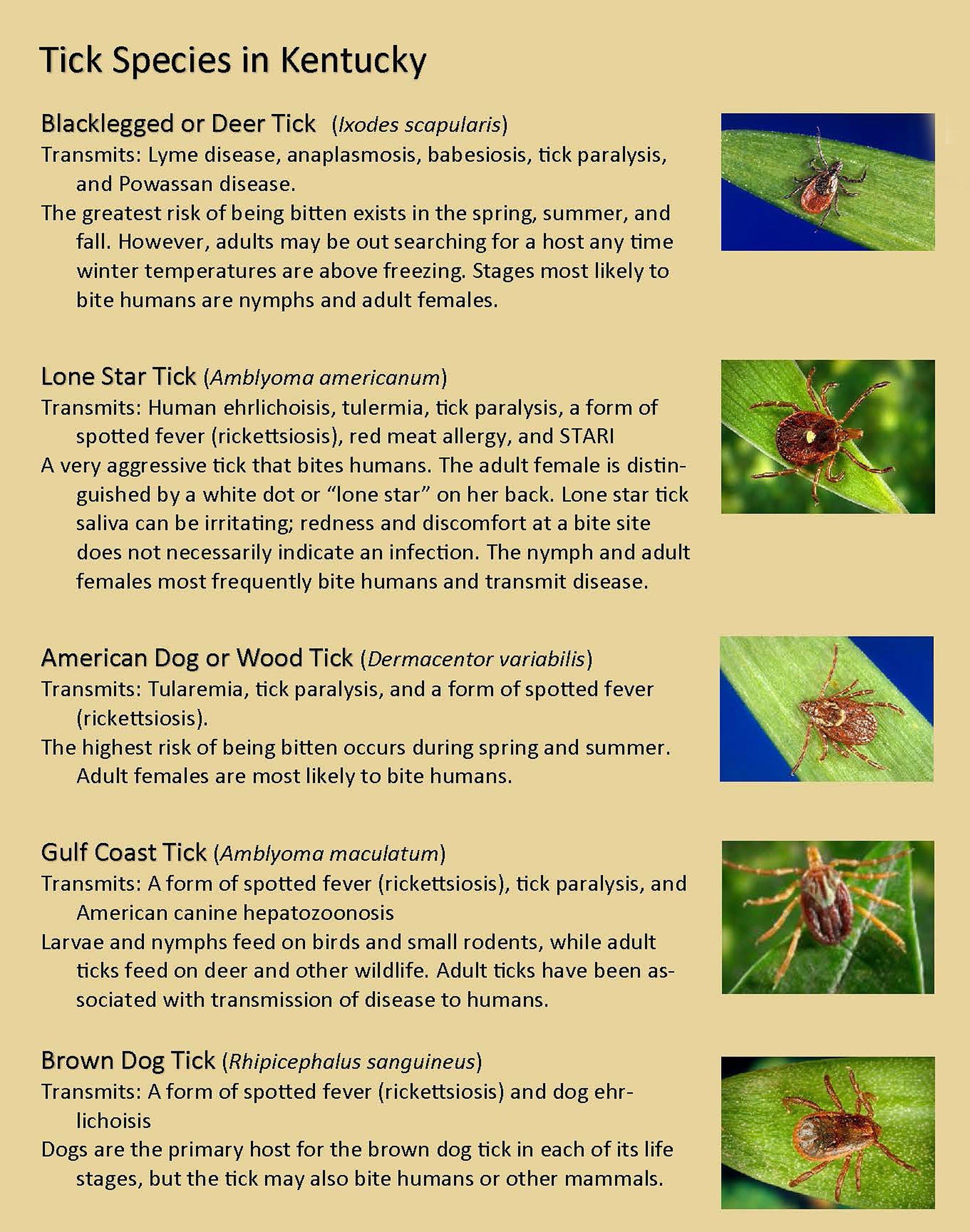

Kerri Martin, senior environmental health technician in Preventive Medicine at Ireland Army Health Clinic, said Lyme is actually not that prevalent in Kentucky.

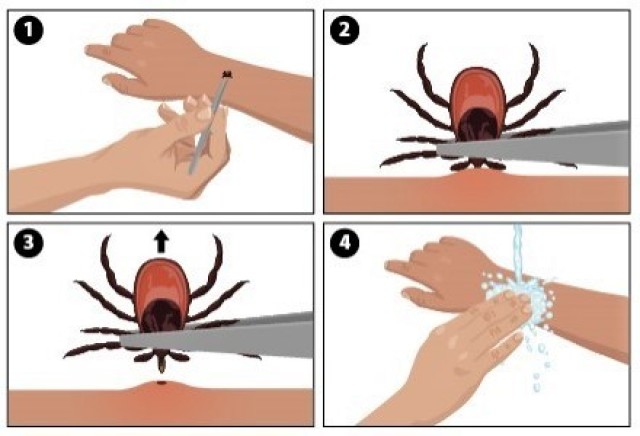

Rhodes admitted to her brother that she had actually been bit by a tick earlier and removed it without incident. It didn’t leave a mark, so she didn’t worry about it.

“In Kentucky, you have a tick on you, you pull it off, you roll out — you live another day,” said Rhodes. “But I still kept getting sicker and sicker until one day at work, it felt like I had concrete flowing through my veins.”

She decided to get checked out by a doctor.

A battery of generalized tests revealed nothing. Rhodes then remembered the conversation she had had with her brother and told the medical staff about the tick bite.

They ran a more specific test.

“A day later, the doctor called me and said, ‘Hey, we ran the test for Lyme and Rocky Mountain spotted fever —’ I had never heard of Rocky Mountain spotted fever,” said Rhodes. “He said, ‘You’ve got Rocky Mountain spotted fever, and we need you to start a round of doxycycline.”

Rocky Mountain spotted fever is the most commonly reported spotted fever disease in Kentucky, according to the Kentucky Department of Public Health. In fact, in 2017 Grayson County, just south of Hardin and Breckinridge, had the greatest number of reported cases in the state, with slightly lesser numbers fanning north in Hardin, Breckinridge, Larue and Meade counties.

Rhodes had been bit in Meade County.

Martin said Rocky Mountain spotted fever is also the most commonly reported tick-borne disease at Fort Knox.

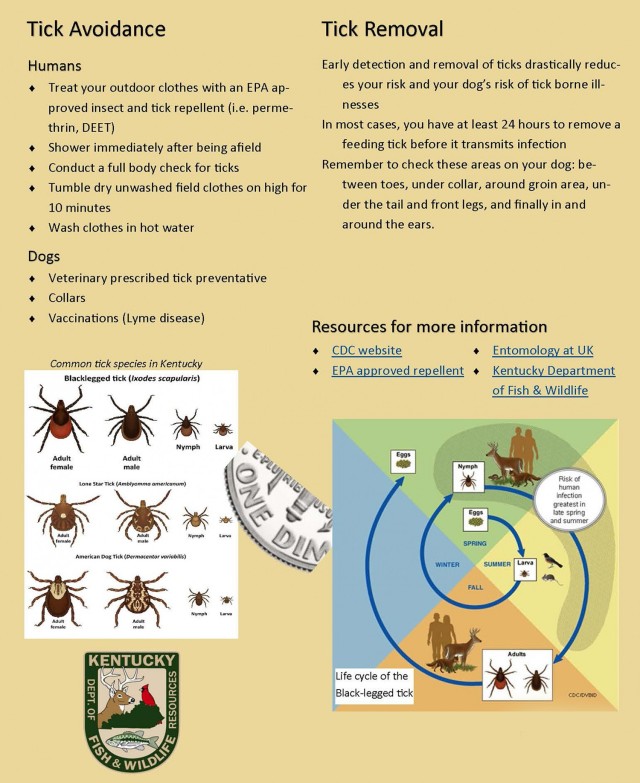

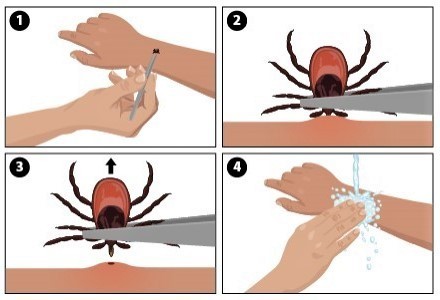

The U.S. Army Public Health Center has established a program called MiLTICK to gather information on the ticks that are biting humans. Martin said the program encourages those who have been bitten to collect the tick, freeze or double seal it in plastic baggies, and drop it off to her offices on Clairborne Street, off of Wilson Road.

“We can only send a tick in if it’s actually bitten someone,” said Martin. “If it’s just crawling on someone, we can’t send it in.”

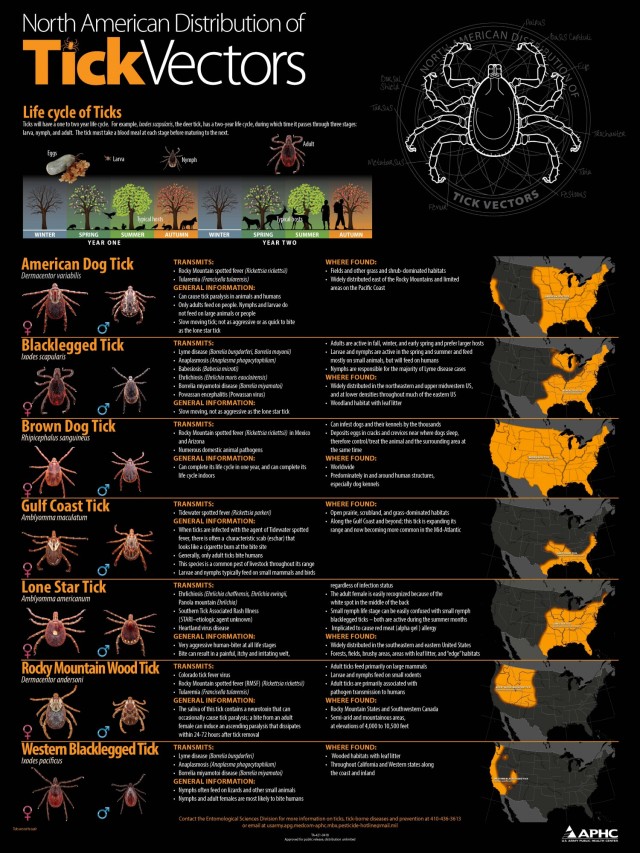

Martin said the center tests each tick to determine its species, the gender, how engorged it is, and its stage of life.

“To advance to the next stage in life, a tick has to have a blood meal,” said Martin, “and how engorged it is tells us is how long a tick has been attached.”

Martin explained that in some tick-borne illnesses, there seems to be a correlation with the level of engorgement and an increased risk of infection.

“The longer a tick is attached, the greater the chance that the pathogen of a tick-borne illness can be transmitted,” said Martin. “[APH Center personnel] determine all of that.”

The information gathered identifies what species are biting at a particular time of year, where specifically, and what pathogens are circulating in the ticks on the installation.

“All of this information comes together and can help us with risk assessments when we look at the risk to Soldiers from an entomology standpoint,” said Martin. “When we want to protect the Soldiers from tick-borne illnesses, very often it comes down to preventive measures."

For Rhodes, preventive measures were not an option. In early May 2012, the thought of keeping the tick and sending it in for testing was not even a consideration.

Rhodes didn’t go to the urgent care center until around the end of May or beginning of June. Her doctor told her if she had gotten tested within a week of having flulike symptoms, a fever or spots, the effects of Rocky Mountain spotted fever would have likely been minimal with a chance to cure it.

“I didn’t have spots or a fever,” said Rhodes. “I’ve actually met three people who live in this area and have tested positive for Rocky Mountain spotted fever, who didn’t have spots or a fever.”

She advised being tested for it if people develop flulike symptoms during the summer months, especially if they have been in areas prone to tick attachments.

Despite the doxycycline treatments and steroid injections, Rhodes got sicker for a while. She said the reason was because she had missed that one-week window for treating the disease. She later found out she also had two co-infections: ehrlichiosis and babesiosis.

According to the CDC, babesiosis occurs by parasites that infect a host’s red blood cells. The infection’s effects range from being asymptomatic to life threatening. Ehrlichiosis can cause one or more of the following symptoms: fever and chills, headaches, malaise, muscle pain and gastrointestinal symptoms.

Rhodes continued to struggle with fatigue, heaviness in her arms and legs, and stomach pains.

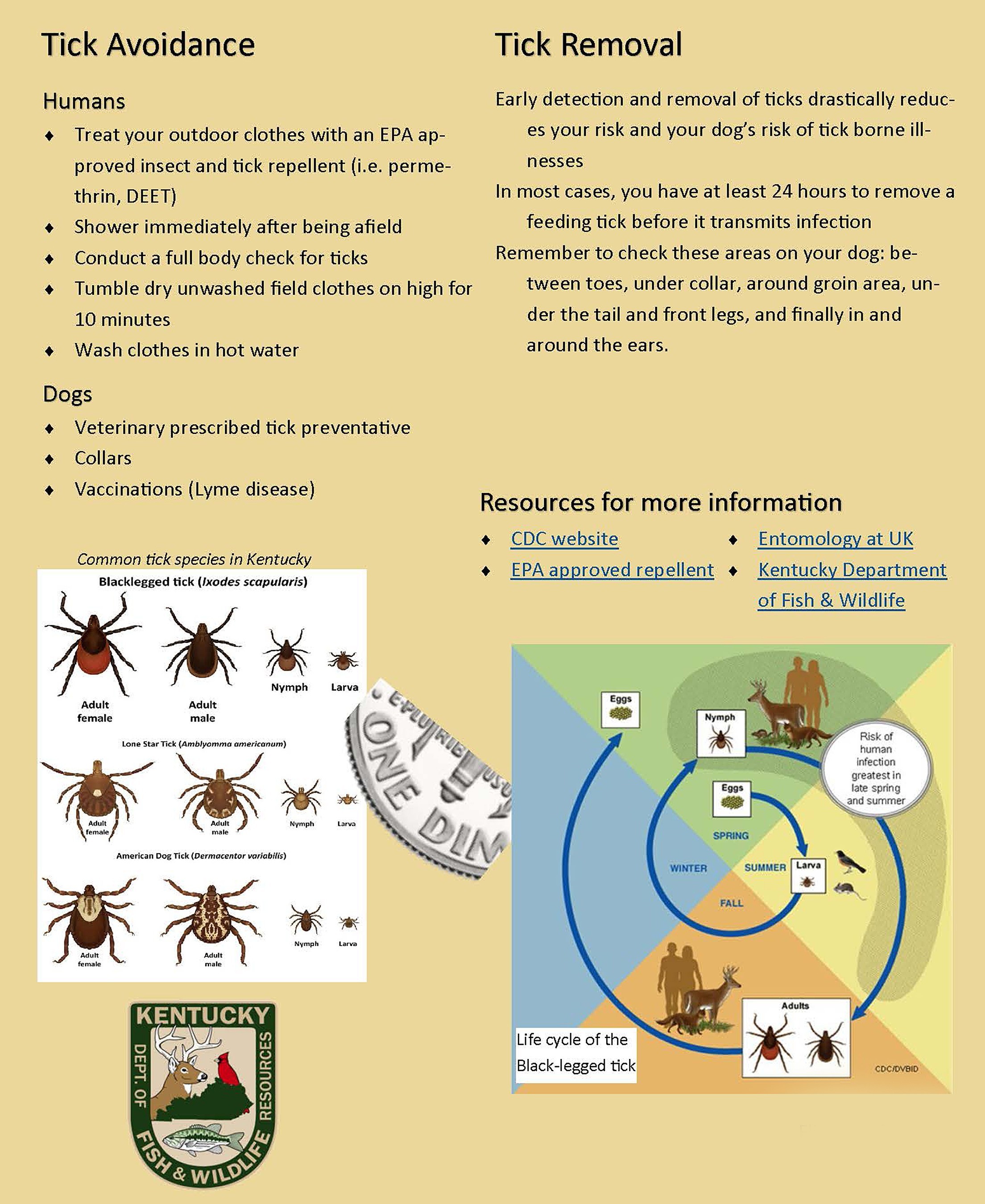

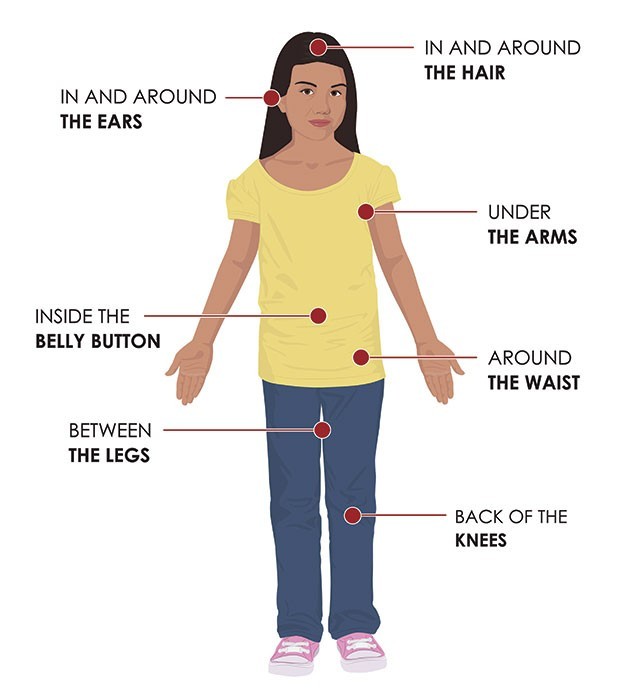

Martin said the Army has plans in effect to fight against tick diseases, including a Defense Department insect repellent system that treats Soldiers’ uniforms with permethrin, recommendations to apply DEET to exposed skin each time they will be in the field, proper wear of the uniform to include tucking pants inside of boots to prevent ticks from crawling up inside exposed pant cuffs.

For those living and working at Fort Knox, Martin recommends wearing appropriate clothing including light colors to easily spot ticks crawling along. She also recommends staying on trails, away from where ticks lurk, which is usually in tall grass and underbrush areas.

“You’re trying to prevent the ticks from attaching to exposed skin,” said Martin. “A tick crawling on you is not going to transmit a pathogen, so we’re trying to prevent tick bites.”

Rhodes said Martin and others in preventative health do a great job in encouraging people to keep from getting bit.

“I’m glad that Fort Knox takes enough care to try and remind Soldiers that there are ticks out there,” said Rhodes. “It’s great that they also research and take the time to understand ticks,” said Rhodes.

Since suffering the last nine years with complications including autoimmune disorders. She’s been hospitalized four times as a result. She suffers from rheumatoid arthritis. She also has developed multiple food allergies.

“The tick wrecked my immune system,” said Rhodes. “When your immune system gets wrecked, it’s just a downward spiral of issues.”

As a result of her struggles, Rhodes has become a big advocate for wearing bug spray whenever Soldiers are training in the field.

“Before training, leaders will run through all the safety protocols, and they’ll tell Soldiers about ticks; still, some don’t take it seriously,” said Rhodes. “I had a Soldier say before, ‘I don’t need bug spray,’ and I said, ‘I don’t know — I could tell you a story about a girl who’s had about $275,000 worth of procedures done to her in the last nine years.

“’You might want to wear bug spray.’”

Social Sharing