WASHINGTON -- Then-2nd Lt. Ralph Puckett Jr. had been finalizing his deployment preparations as a member of a replacement depot out of Camp Drake, Japan, when he heard his name echo through a nearby intercom system.

Having volunteered to support the joint U.S. and U.N. mission during the Korean conflict in 1950, Puckett responded to the call and found himself reporting to Lt. Col. John H. McGee at the Eighth Army headquarters.

McGee explained the launch of a provisional Ranger company to support dangerous missions throughout the Korean Peninsula, said retired Lt. Col. John Lock, a military historian and close friend to now-retired Col. Puckett.

Puckett, a recent graduate of the U.S. Military Academy, had limited infantry training and no combat experience. Yet, he still volunteered without knowing any other details.

"I said, 'Sir, I would volunteer for any position in the company. That includes being a platoon leader, squad leader, or anything. I would be proud to serve as an Army Ranger,'" Puckett said.

After two of the unit’s three officer billets had been filled, McGee needed to select a company commander. The pair of officers he previously chose were West Point graduates and spoke highly of their former classmate, Lock said.

The next day, McGee tasked Puckett to stand up and lead the Eighth Army Ranger Company in August 1950. He also received a promotion to first lieutenant shortly after taking command.

"I felt a stab right in the stomach,” Puckett, 94, recalled. “I knew I didn't have one ounce of experience, but I also knew I was getting the best opportunity that I would ever get in my life."

The company was divided into two platoons and comprised of 74 enlisted Soldiers and three officers, Lock said. To make things more complicated, infantry personnel were not authorized to join the unit due to mission requirements and high demand.

Hundreds of Soldiers volunteered for the provisional unit, allowing him to select Soldiers based on their weapons qualification scores, duty performance, athletic ability, and desire to serve as an Army Ranger.

"[Puckett] had to select his company from service and support personnel," Lock explained. "He spent time interviewing clerks, truck drivers, maintainers, and cooks.

"All he cared about was are they physically able to do the job? Are you willing to meet the standards? And will you follow me? Those were Lt. Puckett's criteria," Lock added.

With his selections in place, the company relocated to then-Pusan, South Korea, where they started seven weeks of specialized training at the Eighth Army Ranger Training Center. The needs of the Army reduced the unit’s preparation to five and a half weeks. Soldiers who could not meet the standard were cut and replaced with Korean Augmentation to the United States Army soldiers, known as KATUSAs.

The company activated in early October 1950 and was redesignated as the 8213th Army Unit.

Taking of Hill 222

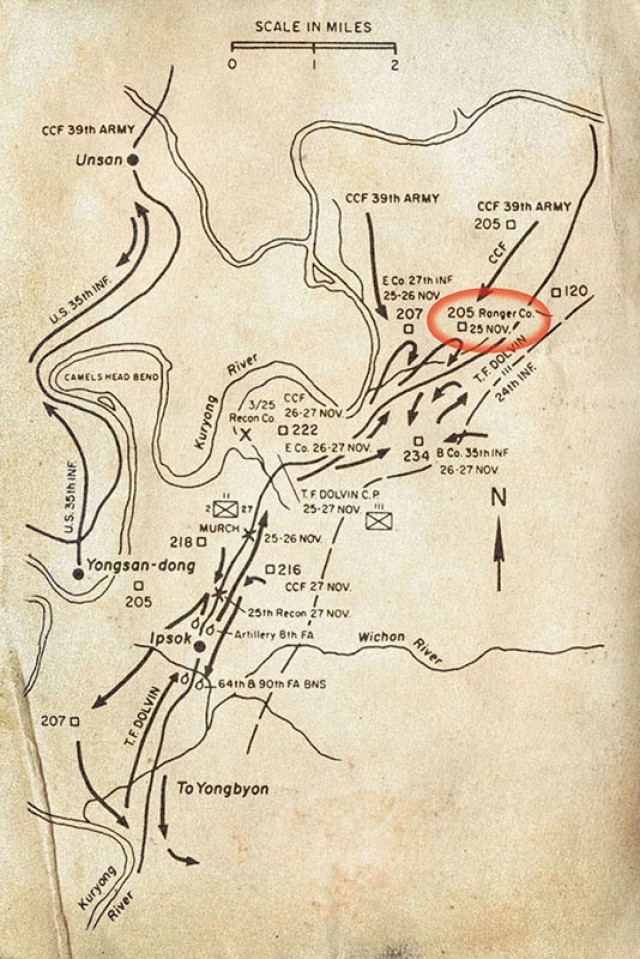

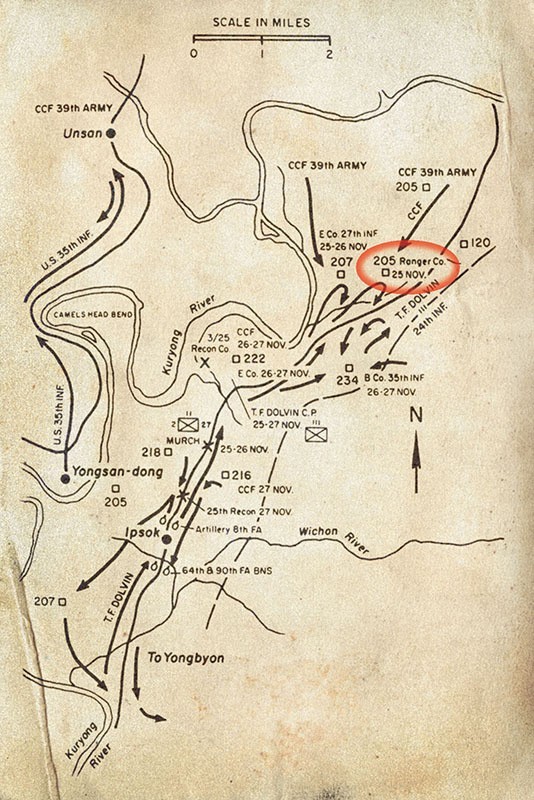

Puckett recalled the freezing temperatures that he and the Ranger company had to endure as the lead assault element while under the 25th Infantry Division as part of Task Force Dolvin, Lock said.

Without proper cold-weather gear, ground forces were ill-equipped to handle the harsh environmental conditions. Food and ammunition were also limited, as supply lines struggled to keep up with the Army's advance.

The company continued to push north on the backs of Sherman tanks from the 89th Tank Battalion. As they drew closer toward the Yalu River and Chinese border, the company seized Hill 222 on Nov. 24, but suffered several causalities from both enemy and friendly tank fire, Lock added.

During the taking of Hill 222, Puckett ran across open terrain and jumped on top of a tank at one point during the assault. He banged on the hatch with his rifle to get the tank crew’s attention to tell them to cease fire, Lock said.

The battle for Hill 222 took a toll on the company, as Rangers dug foxholes into the frozen ground to stay overnight, Lock said. Freezing temperatures and a risk of hypothermia halted any opportunity for rest. Many of them even removed their boots and stuck their feet in another person's armpits to prevent frostbite.

On to Hill 205

The following morning, the company received orders to secure Hill 205 and defend the critical position overlooking the Chongchon River, Puckett said. Intelligence reports from the 25th ID reported more than 25,000 Chinese fighters in the area, severely outnumbering the 57 Rangers and Korean soldiers Puckett picked for the upcoming mission.

Riding on the back of Sherman tanks, the Eighth ARC and 89th Tank Battalion encountered resistance about a half-mile out from the hill. North Korean forces launched an array of mortar, machine-gun and small-arms fire on their position as the Rangers dismounted and prepared an assault.

Sherman tanks from the 89th TB initially did not fire. In need of armor support, Puckett tried to contact the driver inside through a frozen radio near the rear of the tank, Lock said. Realizing that he couldn't get through, he resorted to his old ways -- jumping on tank and beating on the hatch with the butt of his rifle.

After a quick discussion between Puckett and the tank crew, the tanks engaged the enemy’s position.

Yelling, "'Let's go, Rangers!'" Puckett sprang into action and led his company across 800 yards of frozen rice paddies and wide-open terrain, as his two platoons split up to flank enemy positions on the hill, Lock said.

Soon after, a concealed heavy-machine gun opened fire and pinned one of his platoons, Lock added. Taking a risk, Puckett ordered his Rangers to take out the gunner's nest as he ran across the open field and exposed himself to enemy fire. It took him three passes before his Rangers could locate and eliminate the fighter's position.

Now at the base of the hill, Puckett ordered his Rangers to fix bayonets as they moved up the slope. They met little resistance as they secured the top of Hill 205. In total, six Rangers were wounded and one South Korean soldier died during the initial assault.

"We began to put in a perimeter defense," Puckett said. "We always defended 360 degrees because we were always alone. We had our individual weapons, machine guns, rocket launchers, and hand grenades -- that was it."

The closest Army ground force unit was over a mile away, Puckett recalled. The company needed to establish a strong line of defense against an enemy counterattack they knew would come.

Defending Hill 205

As the company made their final preparations, Puckett and a handful of Rangers crossed back over the open field to battalion headquarters. While there, he procured another radio, supplies and coordinated artillery fires.

"I got with the S3, and he briefed me on the situation. It looked like the Chinese were stiffening, [and] things were getting harder and tougher," Puckett said.

Puckett returned to Hill 205 around 10 p.m. with another Ranger and supplies. Soon after his arrival, he heard a series of whistles and bugles -- a signaling tactic employed by the Chinese to organize an attack.

The area turned into chaos as the enemy opened with heavy mortar and machine-gun fire on Hill 205 and the surrounding area. China had officially entered into conflict against the U.S. and U.N. forces. The initial assault was the first of six battalion-sized attacks against Puckett’s unit.

"I called on artillery and got them to fire on one of those concentrations that I'd already planned,” Puckett said. “That's what prior planning does for you."

Several "danger close" artillery strikes held off the first wave of the attack. Through all of it, Puckett circled his defense perimeter to check on his Rangers and direct fires, Lock said.

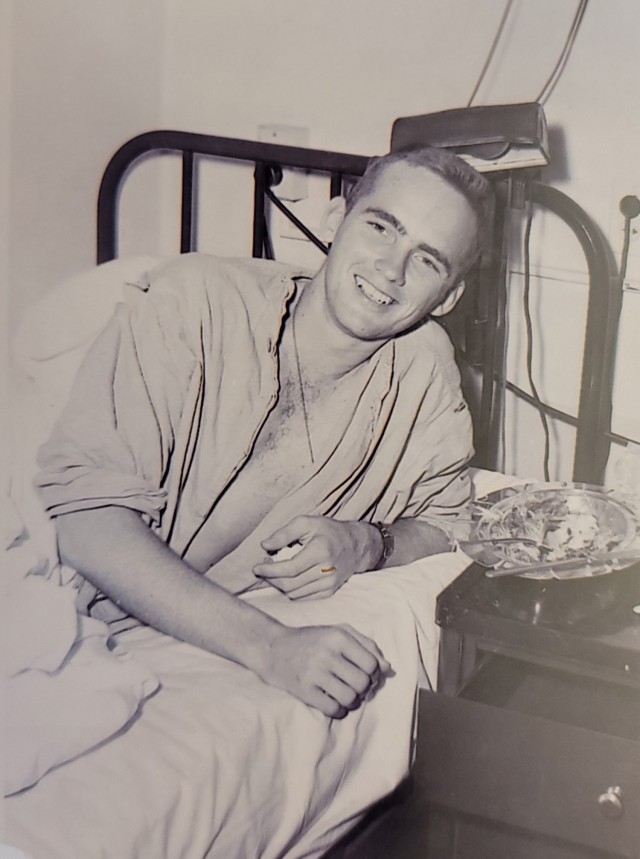

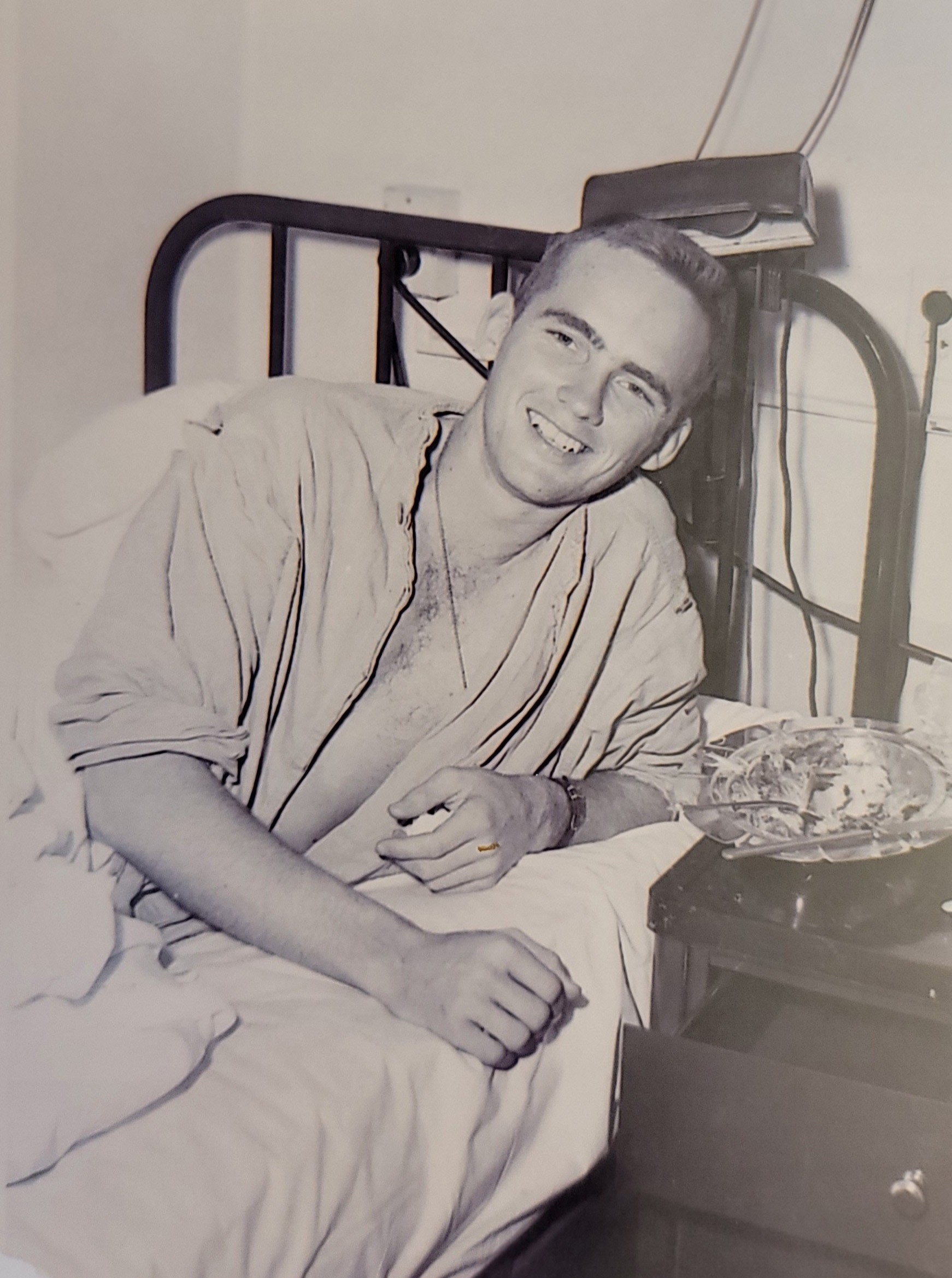

The unit sustained several casualties during that first wave, including Puckett, who took grenade shrapnel to his right thigh. He stumbled back to his foxhole with blood running down his thigh and was met immediately by his two platoon leaders, Lock said.

All the while, he refused to be evacuated. Puckett directed his company and waves of artillery support through additional counterattacks. He continued to leave his foxhole during each wave to observe the enemy's movement, motivate his Rangers, and call in artillery where they needed it most.

"[Artillery] was the predominant power on the battlefield," Puckett said. "It saved our necks ... and broke up the attack against an overwhelming force. Fortunately, we had no short rounds that landed [in our] perimeter."

Ammunition and supplies were running low as the number of casualties on both sides continued to increase, Lock said. At one point during the fight, Puckett gave up his extra rounds to his Soldiers but kept one eight-round magazine.

Even after being wounded a second time, he pushed past the pain and refused to leave his men behind, Lock added.

Puckett also put his own life at risk to try and flush out an enemy sniper taking shots from the shroud of darkness, Lock added. Even with a wounded leg, he ran across an open area on three separate occasions to help his Rangers isolate the sniper's position.

"When 1st Lt. Puckett exposed himself intentionally to enemy fire, he did it because that was who he was," Lock said, paraphrasing comments from Soldiers that he led. "It needed to be done, and somebody needed to do it. He was never going to ask anybody else to do a job that he wouldn't do himself."

Overrun

The aggressing Chinese changed their tactics during the sixth wave in the early hours of Nov. 26, Lock said. A battalion-sized force started to overrun Hill 205 after putting heavy firepower on one area of the company’s defenses.

With little to no options, Puckett ran back to his foxhole and requested artillery support, only to determine that there was no support to give, he said. Backline artillery support was occupied on a different fire mission.

"I said, 'We've got to have it. We are under heavy pressure,'" Puckett said.

Puckett ordered his Rangers to fix bayonets and prepare for what would be the final counterattack on their position.

Heavy mortar fire rained down on the remaining Rangers and inflicted significant casualties upon the force. Severely wounded from one of the blasts, Puckett ordered his Soldiers to withdrawal to safety and leave him behind, Lock said.

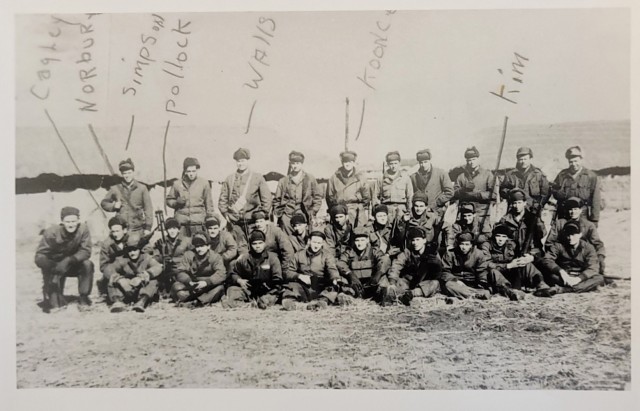

"I was lying there unable to do anything, and I could see three Chinese about 15 yards away from me bayoneting or shooting some of my wounded Rangers," Puckett said. "All of a sudden, two of my Rangers charged up the hill, Pvt. 1st Class Billy G. Walls and Pvt. 1st Class David L. Pollock. They shot [and killed] the three Chinese.

"When they came over, Walls said, 'Sir, are you hurt?'" Puckett added. "I thought it was the dumbest question I heard in my life. I said I was hurt bad and they should leave me behind."

Disobeying their commander's orders, Walls scooped Puckett over his shoulders and started moving down the hill while Pollack provided rear guard, Lock said. As they crashed through the brush, the three of them could hear the bullets zip by as the enemy fired blindly in their direction.

Physically and mentally drained, Walls had enough energy to carry his commanding officer halfway down the hill before setting him on the ground, Lock said. Together they dragged Puckett down the rest of the way to safety and loaded him on the back of a tank with other wounded Rangers.

Once onboard, Puckett asked one of the tank commanders to radio in a final request, a "Willie Pete" artillery concentration, or a white phosphorus incendiary munition attack at the top of the hill. Of the Rangers on the mission, 10 were either killed or missing with another 31 wounded.

"I have been proud, very proud of those Rangers," Puckett said. "They were trained until they were highly skilled and physically, mentally, and morally tough. They were highly skilled as a small unit and a company. And they had confidence in their leaders, themselves, and company and made me believe that we were the best company in the Army."

Puckett was initially awarded a Distinguished Service Cross for his heroic actions and devotion to duty that day.

"Good training is the basis for success. Without it, you are not going to make it," he said.

Honoring the company

For the past 18 years, Lock worked tirelessly to upgrade Puckett's Distinguished Service Cross to the Medal of Honor. As a former Ranger and assistant U.S. Military Academy professor, he came across the colonel's heroic story while researching Ranger history in the early 90s.

"I was exceptionally embarrassed to realize that I had never heard of him, and I never heard of the battle," Lock said. "I found an opportunity to reach out to him, and he provided additional background information on the Eighth Army Ranger Company and the battle of Hill 205."

Through his research, Lock felt Puckett's actions could meet the requirements for a Medal of Honor. He presented his case to retired Gen. Stanley McChrystal who was a colonel at the time. He agreed with Lock's findings.

Determined to pay tribute to Puckett and the Eighth ARC, Lock started the upgrade process in 2003. His initial request in 2007, along with his subsequent appeal in 2009, were both denied. The Medal of Honor submission requirements only allows for one submission and one appeal.

"Nowhere along the line did Col. Puckett press for this," Lock said. "As we were going through the process and dead in the water, he appealed to me to stop because he didn't want me to continue wasting my time."

Years later, Lock discovered a congressional review of the Medal of Honor process to determine why all recipients from 2001 to 2010 were bestowed the nation's highest honor posthumously, he said. The secretary of defense later discovered that the military services inadvertently shifted the consideration requirement from "a risk of life" to "a loss of life," Lock said.

As the secretary of defense ordered a full review of all service crosses and Silver Stars in 2016, Lock found his next opportunity. He gathered his submission paperwork, added additional letters of recommendation from former and current general officers, and included a memorandum with the defense secretary's findings.

Despite exceeding the upgrade submission requirement, the Army's appeal board denied Lock's request yet again, he said. Failing to take no for an answer, he shifted his tactics and wrote a letter to Sen. John McCain, the Senate Armed Services Committee chairman, who agreed to reach out on Puckett's behalf.

Shortly after that, the appeal board responded, denying Puckett's request. However, this time they included details about an alternative appeal process through the Army award corrections board, Lock said.

"All I did was compile a narrative about the story the Eighth Army Ranger Company wrote in blood on that hilltop," Lock said. "I am honored to be part of this because it is the right thing to do."

After submitting one final request, Puckett's upgrade was approved in 2020. Later, the secretary of the Army and secretary of defense both signed off on the recommendation.

The package was then sent to Congress for approval under the National Defense Authorization Act. To streamline the process, Lock advocated for congressional sponsorship starting in Georgia, Puckett's home state.

On Friday, he is scheduled to receive the Medal of Honor from the president.

"I am still surprised" to receive the medal, Puckett said. "I feel the credit goes to those Rangers who are up on that hill with me. They are the ones who worked and the ones who fought. They're the ones who earned the medal. And I'm proud to be the commander of that company, but they deserve the credit."

(Editor’s note: An interview conducted by the Witness to War Foundation contributed to this story.)

Related links:

Social Sharing