Most good Army logisticians have developed an “anticipatory sense” for Army requirements. They seem to know, intuitively, what is needed before it is needed. The great logisticians then act upon that intuition and solve problems before they limit operational reach, endurance, or freedom of action of Army forces. They learn through training, which is guided by doctrine and reinforced by experience. Training is the seed from which intuition grows, and experience germinates that seed.

Over the years, I have cultivated a pretty good anticipatory sense, but my intuition remains Army-centric, which proved problematic when I was a theater sustainment command (TSC) commander in Europe. I am concerned that our training and exercises remain generally Army-centric. We must develop an anticipatory sense for Army support to other services. In order to do that, we must change the way we teach and train.

In 2016, as a new TSC commander, we were planning the arrival of an ammunition vessel to a port in Germany. I understood, through experience, what needed to be done. After receiving briefs from the executing units, I went down to oversee operations. What I hadn’t anticipated was the fact the shipment included ammunition for the other services operating in United States European Command (USEUCOM). Trucks and personnel from my subordinate Army units were in place and ready to distribute across the region, including the movement of Air Force ammunition to several European storage locations. My anticipatory sense was limited to the “who, what, when, and how” of Army requirements and operations. I had not fully considered my responsibilities to our joint teammates in the European theater.

The Army’s TSCs are the overarching theater-level headquarters for executing such cross-service, cross-agency logistics responsibilities. Had the 21st TSC not enjoyed the continuity of a robust augmented table of distribution and allowances consisting of tenured American and German civilians, we may have been surprised by our requirements to support the Air Force.

I’d like my shortsightedness to stand as a lesson for all Army sustainers. Recognize that large-scale combat operations conducted across multiple domains require the full capabilities of a joint force. Sustainment of that joint force relies on the convergence of our nation’s logistics assets and capabilities. If the Army, the foundational logistics provider to the joint force, is to fulfill its responsibilities, our logisticians must stretch our running estimates and expand our planning. We must extend our anticipatory sense to our sister services and military departments, learn what they need and when they need it so that we are prepared to step up as the lead service for logistics. That requires a full understanding of both the current and future authorities, responsibilities, and expectations for logistics support beyond our own institutional walls.

Army logistics is, and will be, foundational to joint operations in a multi-domain environment. We must be ready to provide the capacity and capability the joint force needs to deploy globally, maintain a forward presence, and sustain operations that protect and advance U.S. strategic objectives.

The elements of Army logistics—maintenance, transportation, supply, field services, distribution, operational contract support, and general engineering—have long served as the backbone required to support joint operations. That support is empowered by way of three primary authorities:

- Army Title 10 requirements. Each service is responsible for the sustainment of the forces it allocates to a joint force. In other words, we must be prepared to support our own needs in a joint operation.

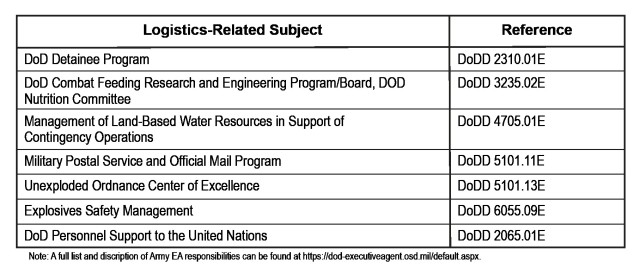

- Executive Agent (EA) responsibilities. A broad delegation of authority from the Secretary of Defense to service secretaries or combatant commanders to provide specific, mostly administrative, support to other U.S. Government agencies or service components. As the executive agent for seven globally integrated logistics responsibilities (see Figure 1), the Army ensures the other services have sufficient capacity and capability to execute their missions around the globe.

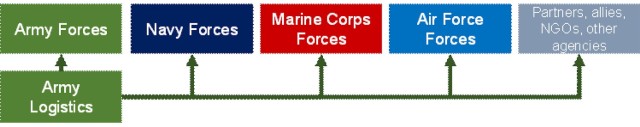

- Combatant Commander (CCDR) authority. When the Secretary of Defense directs the Secretary of the Army to assign forces to unified and specified combatant commands, the CCDR exercises directive authority for logistics and may assign lead service responsibilities, such as providing common user logistics support. The assignment of a lead service is beneficial in that it reduces logistics redundancies and the overall logistics footprint; however, this also requires new support relationships and joint operating procedures (see Figure 2).

External support responsibilities assigned to the Army fall under the non-doctrinal umbrella term Army support to other services (ASOS). Historically, the logistics support provided to other services, agencies, multinational forces, and non-governmental organizations has included ground transportation (both personnel and equipment), fuel (Class III bulk and package), food and water, munitions, medical supply and services, veterinarian services (food safety), contract support, and supply services. The following are examples of specific Army support provided to the joint force:

Tactical water: DOD Directive 4705.01E designates the Army as EA for the production, storage, and distribution of tactical water, with production being the most critical contribution to the joint force in a tactical environment.

Petroleum operations: Although Defense Logistics Agency (DLA) is the EA for fuel, the Army is responsible (in accordance with DODD 4140.25) for all inland distribution of that fuel, especially in a contested environment. When DLA is unable to provide support, the Army is responsible for fuel distribution from the high water mark to the point of need.

Mortuary Affairs: Although there is no longer a designated EA for mortuary affairs, the Army is the lead service for such responsibilities for USEUCOM, United States Indo-Pacific Command (USINDOPACOM), and United States Central Command. As a result, the Army has the only active mortuary affairs capability to receive, store, process, and prepare remains for repatriation or internment. The Army is also the only service capable of safely receiving, storing, and handling contaminated remains.

Contingency contracting: The Army has been appointed the lead service for contingency contracting by the combatant commander within USEUCOM and United States Africa Command, and the Army supports the Air Force in this role in USINDOPACOM.

The joint force already leverages Army resources and capabilities. Within the evolving Joint Warfighting Concept (JWC), that reliance deepens. The JWC purposefully maximizes the complementary and reinforcing effects of each service through intentional interdependence. Under this future warfighting concept, the Army anticipates the assignment of lead service for logistics, requiring sufficient capacity and capability to execute globally integrated logistics in support of other military services, allies, and partners. To take on the expanded logistics requirements, we need to translate internal Army operations to better support the joint force. The Joint Concept of Contested Logistics (JCCL) is the instrument for that translation.

As one of the supporting concepts under the JWC, the JCCL is the framework for projecting, supporting, and sustaining the joint force in an environment that is contested across all domains, from the homeland to the combined or joint operations area. The desired end state of the JCCL is a U.S. force able to retain sufficient strategic advantage to deploy and sustain a joint force that functions effectively, responds decisively, and wins. The JCCL helps DOD senior leaders prioritize and make investment decisions about future logistics capabilities as they balance risk and resources over force employment, force development, and force design horizons.

The JCCL relies on a convergence of assets and capabilities to deploy globally and sustain the joint force from the strategic support area to positions of advantage in support of national objectives. This includes establishing a forward presence as well as close cooperation with the national industrial base, commercial industry, and joint and multinational partners.

The Army will use the JWC and the supporting JCCL to define logistics investment priorities across the Army planning horizons of force employment (near-term), force development (mid-term), and force design (far-term).

Victory in a contested operational environment depends on the robustness of the Army’s global posture and organic industrial base. To pursue a global posture that offers positional advantage and access to resources, the Army has taken steps to strengthen multinational partnerships and develop access, basing, and overflight (air base opening) agreements that will enhance global responsiveness, establish a benign presence, and expand the availability and readiness of pre-positioned resources. The Army prepositioned stock program, likewise, enables the rapid build-up and movement of combat power and serves as a strategic deterrent by demonstrating our national resolve to support allies and partners.

The 26 depots, arsenals, and ammunition facilities that are part of our organic industrial base play a critical role in sustaining the Army and joint force. The combination of the facilities, funding, artisan workers, and a predictable and stable workload is crucial to maintaining capabilities necessary to one day support the war fight.

Future changes in the character of war demand full and continuous integration of national instruments of power and influence, which requires creative approaches to sustainment, highly effective coordination across services and with partners, and a deeper understanding of the implications of disruptive and contested logistics environments.

To prepare, I challenge the Army sustainment community to amplify its joint logistics knowledge through both training and exercise. Understand how all the pieces fit within the broader joint environment, then train and seek out opportunities to build the appropriate operational muscle memory.

Engage in joint workshops, field experiments, war games, tabletop exercises, and simulations so you know what our sister services require and how they operate. First, seek to develop an intuition for ASOS, then develop strategies and possible workarounds for accomplishing the mission under persistent attack and across all domains.

The U.S. Army’s recent logistics contributions to the joint environment highlight its foundational capability and strategic signaling. In 2018, we rapidly positioned supplies on the Korean Peninsula, which enabled joint force access during the competition phase and telegraphed to our adversaries our determination. And throughout the conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan, the Army provided overwhelming logistics support to all forces. These operations are but two examples of our unique expeditionary logistics capability to provide an advantage during both the competition and crisis, as well as serve as a deterrent to conflict.

U.S. Army logistics will continue to be a required strategic enabler of the joint force. Our ability to project and sustain forces from a contested strategic support area to the tactical point of need must remain our global competitive advantage. We must develop and maintain a reflexive competence and intuition for sustaining a joint force in a multi-domain environment. Our training and exercises must be aimed at supporting the joint force in order to develop the anticipatory sense required to solve problems before they limit operational reach, endurance, or freedom of action.

-------------------

Lt. Gen. Duane A. Gamble, Deputy Chief of Staff, Headquarters, Department of the Army, G-4, oversees policies and procedures used by U.S. Army Logisticians. He has masters of science degrees from Florida Institute of Technology, and Industrial College of the Armed Forces.

-------------------

This article was published in the April-June 2021 issue of Army Sustainment.

RELATED LINKS

The Current issue of Army Sustainment in pdf format

Current Army Sustainment Online Articles

Social Sharing