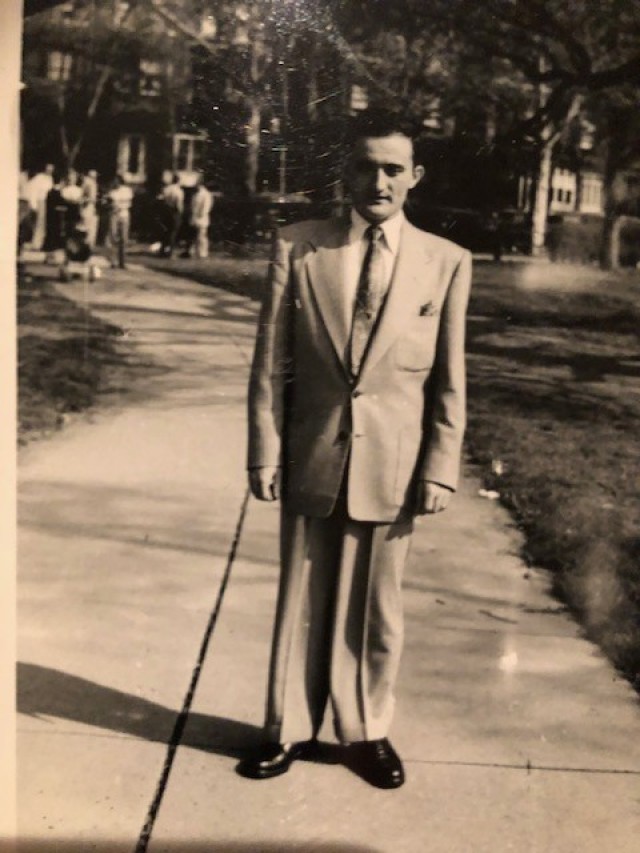

Henry Estreicher

FORT KNOX, Ky. — Henry Estreicher was once just a typical young man with typical hopes and dreams. A lifetime ago.

Growing up in the small farming and forested community of Myszkow in Southern Poland, he could easily have been overlooked among his eight siblings, four of whom were also boys. Now living in California, the 94-year-old recalled the day all those hopes and dreams suddenly vanished.

“They took our whole family to Auschwitz, and they gave us numbers,” said Estreicher. “We stayed up all night to get our number. You no longer had a name. I was 140398. They called you by your number, you had to memorize it, and if you didn’t answer quickly when it was called, you got beaten up. Nobody could escape because of it.”

In an essay written by Andrea Herman, Estreicher described his life prior to the Nazi invasion of Poland in stark contrast. His hometown was blissful, where the roughly 900 Jewish families worked closely among non-Jewish families, shopped at the same stores, and played in the same neighborhoods. His home life was equally blissful.

“He had a loving and religious family who attended religious school and synagogue on a regular basis,” Herman wrote.

All that changed in 1939 when at the age of 13, Estreicher learned that German soldiers had closed down his school and arrested the principal and his uncle. The two were never seen again.

The family stayed together in the town, forced to work for the Germans without receiving any compensation, until 1942. For the next year they lived in the Zawiercie Ghetto, about nine miles south of his home, before being sent an hour further south to Auschwitz.

Estreicher recalled how so many old people died in the overcrowded cattle cars on the way to Auschwitz: “Once the cattle train stopped, everyone who was still alive, and could walk, got off.”

Estreicher and his entire family found themselves standing in a line in front of the infamous Dr. Josef Mengele, who became known as a the “angel of death” because of his sole power over who lived or died at Auschwitz. Mengele would point to the left for those sent to their deaths; to the right for those sent to work at the camp.

“He sent me to work,” Estreicher said.

After serving time at Auschwitz, Estreicher said he was then sent to the Warsaw Concentration Camp, after the ghetto there had been converted because of an uprising.

He described the Warsaw camp as the worst of all of them he lived through. He had been sent there to recycle bricks and metal, and load them onto trains to be reused in Germany.

“I was really sick from the typhus,” said Estreicher. “It wasn’t very clean there and I was sick the whole time.”

When word came that the Russian soldiers had effectively surrounded much of the city and the Poles in the camp rebelled, Estreicher said he and many others were then sent to Dachau, a concentration camp just north of Munich, Germany.

Once they arrived in 1944, prisoners were separated again, and Estreicher found himself in nearby Mildorf, where he worked in an underground German airplane factory.

All that changed in April 1945 with a new threat coming.

Estreicher said he and well over 1,000 other prisoners were hastily ordered into cattle cars on a train headed south. They knew the Nazis planned to haul them to a secret spot where they would soon be forgotten — their usefulness to the Nazis had come to an end.

“They were trying to take us to the mountains to kill us,” said Estreicher.

After several stops and starts, the train suddenly halted for much longer than usual. After a while, suspicions spread among the prisoners that the guards had abandoned them. Estreicher and others disembarked the train and started to travel on foot when the German soldiers returned and ordered them back in the cars.

“The German soldiers had run away, afraid that the Americans were nearby,” said Estreicher. When the Germans realized the Americans were not as close as originally thought, the journey began again in haste.

A little while later, however, the train again stopped, and the soldiers fled. This time, they never returned. Instead, the prisoners were greeted by Soldiers wearing American uniforms.

“We had gotten interrupted by Patton’s Third Army,” said Estreicher, “and we were liberated. I finally felt safe.”

Estreicher traveled back to Poland after the war to search for his family after receiving word that two of his brothers were back in his hometown.

Once he arrived and celebrated a joyous reunion with his brothers, Estreicher discovered that the threat of violence in Myszkow against Jewish survivors still existed under Communist rule. He learned of a Jewish brother and sister who, upon returning, were murdered by Poles who had laid claim to their family home.

“I knew I had to go back to American-controlled Germany right away,” said Estreicher.

Followed within two weeks by his brothers, Estreicher fled Poland. He returned to Germany to live in a displaced persons camp until he could secure travel to the United States. He arrived in 1950 and settled into a new life with an uncle who lived in Philadelphia.

In April 1951, Estreicher was drafted into the U.S. Army as war raged in Korea. After arriving at Fort Knox to attend basic training, he learned how to drive tanks and shoot a rifle. After graduating, instead of Korea the Army shipped him back to Germany, where he was assigned to Third Army -- the unit that had liberated him. They taught him to be a sharpshooter.

His language skills proved to be more beneficial to the Army, however.

“I was given the job of telling the Germans what to do,” said Estreicher, laughing at the irony. He was promoted to the rank of corporal while there.

Estreicher said while the horror of the Holocaust feels like it happened a lifetime ago, his dreams still return to that time, which sometimes concerns him about the hopes and dreams of his children and grandchildren.

“I worry about it sometimes,” said Estreicher, “but I believe America is strong enough to make sure that nothing like that will ever happen again.”

Social Sharing