FORT KNOX, Ky. – It’s a distinction reserved only for those who carry out the most heroic and selfless of acts – the Medal of Honor.

One such recipient rests in Fort Knox’s Main Post Cemetery, far away from the chaos of the Korean War and the actions that would give Master Sgt. Ernest Kouma legendary status after he fought against unbelievable odds for more than nine straight hours.

“Kouma’s [experience] … it’s a story,” said Fort Knox historic preservation specialist Matthew Rector, from the Cultural Resources Office. “I’m honestly surprised they haven’t made a movie about it.”

Having enlisted in the Army in 1940 and serving 31 years, Kouma was no stranger to war.

While he made numerous contributions throughout his military career, it was the course of events on Aug. 31, 1950 as a tank commander in Korea that cemented Kouma’s place in history.

Beyond the call of duty

Close to midnight on Aug. 31, Kouma and his men were suddenly attacked near the Naktong River by a hostile force of about 500 North Koreans. The ambush occurred just after they received orders to protect withdrawing forces, according to the Medal of Honor citation. When the enemy overran the other two tanks in the convoy, Kouma realized his vehicle was the only obstacle standing between the onslaught and the American infantrymen seeking a better fighting position.

“Holding his ground, [Kouma] gave fire orders to his crew and remained in position throughout the night,” the citation reads, “fighting off repeated enemy attacks.”

During one of the worst points of the assault, Kouma changed tactics.

“The enemy surrounded his tank and he leaped from the armored turret, exposing himself to a hail of hostile fire, manned the .50 caliber machine gun mounted on the rear deck, and delivered pointblank fire into the fanatical foe,” the citation reads. “His machine gun emptied, he fired his pistol and threw grenades to keep the enemy from his tank.”

Kouma described the experience in his own words during an interview with the New Philadelphia, Ohio, newspaper The Daily Times on May 7, 1951.

“They got around us and about five of them climbed on the back of the bank. So I climbed out and started using the machine gun,” said Kouma. “They got so close, I tossed three grenades at them and used my .45 [pistol].”

Once his men were able to withdraw their tank, Kouma — despite sustaining serious wounds — maintained the fight as they traversed through eight miles of enemy territory:

“Kouma continued to inflict casualties upon the enemy and exhausted his ammunition in destroying three hostile machine gun positions.”

It is estimated that Kouma killed 250 enemy soldiers during in the defense of his fellow troops.

A lasting legacy

The Medal of Honor citation highlights Kouma’s unyielding bravery during the attack — and afterward.

“His magnificent stand allowed the infantry sufficient time to reestablish defensive positions,” it reads. “While being evacuated for medical treatment, his courage was again displayed when he requested to return to the front.”

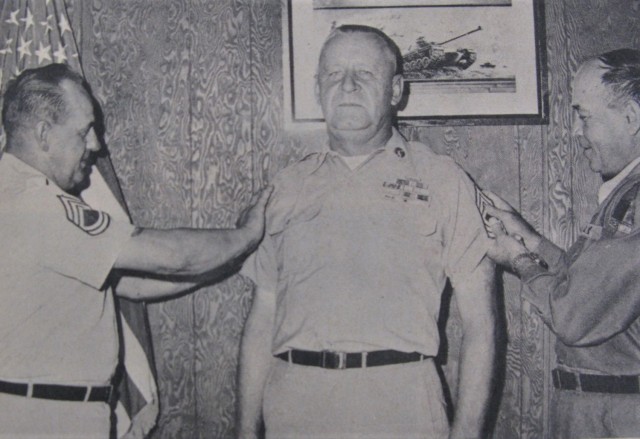

Kouma would later become the first living Korean War veteran to receive the Medal of Honor by President Harry Truman, according to the newspaper article. Nine others had received their awards posthumously.

Following the war, Kouma continued to demonstrate his dedication to his fellow men, according to Rector, when he participated in a 1958 internment ceremony for two unknown Soldiers who were buried at Arlington National Ceremony.

He then had the honor of facing another U.S. President as he presented a folded flag to Dwight D. Eisenhower to conclude the ceremony.

Fort Knox became Kouma’s final active duty station, where he retired and quietly remained in the area until his death in 1993.

A simple headstone lauds his accomplishment, making him the only MOH recipient to be buried in the Main Post Cemetery. Other tributes to Kouma a Fort Knox dining facility named in his honor and a Radcliff, Ky. street that bears his name.

Some would argue that’s just the way he would have wanted it.

Social Sharing