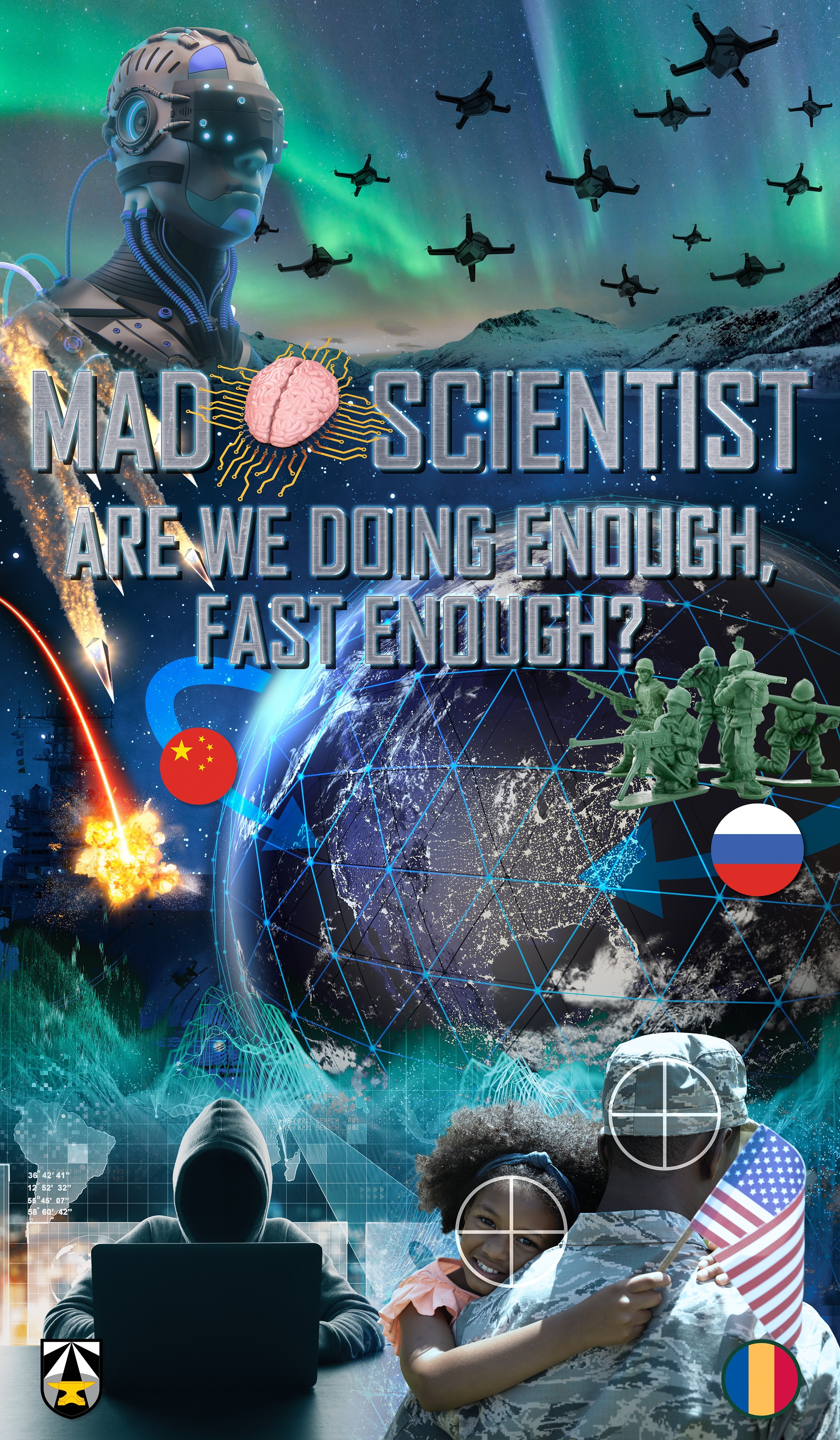

JOINT BASE LANGLEY-EUSTIS, Va. – The U.S. Army's Mad Scientist Initiative leads a series of virtual events focusing on “Are we doing enough, fast enough?” with the emphasis on the future of competition, crisis, conflict, and change. It is paramount for us to explore these critical issues and challenges now to incorporate insights into future force development and structuring.

On February 23, a panel of experts discussing competition was held with: Dr. George Friedman, Founder and Chairman of Geopolitical Futures, John Edwards, U.S. Secret Service's Deputy Special Agent in Charge, Office of Strategic Planning and Policy, Dr. Eleonora Mattiacci, Assistant Professor for Political Science, Amherst College, Dr. Zack Cooper, Research Fellow, American Enterprise Institute, Lecturer, Princeton University, and Adjunct Assistant Professor, Georgetown University, Collin Meisel, Program Lead, Diplometrics, Frederick S. Pardee Center for International Futures, University of Denver, sharing their insights into what challenges the next decade will bring to not only the U.S. military but also the world at large.

The U.S. Army faces multiple, complex challenges in tomorrow’s operation environment. Potential adversaries and our pacing threats will seek to achieve their national interest short of conflict and will use a range of actions from cyber to kinetic against unmanned systems staying below the threshold of armed conflict. The globalization of the world, in terms of commerce, communications, and stopping short of war has created vulnerabilities and openings on who has offensive capabilities that were previously limited to state actors.

What do we need to do in the next decade according to our five panelists? Adopt Strategic deterrence: “seize your own narrative,” be more agile, adopt a denial strategy (denial is the ability to affect somewhere without being physically present), and “get comfortable with contestation and get comfortable with collaboration.” As we discuss what panelists impart, a good perspective to keep in mind, as Cooper said, “This is not a competition between the U.S. and China over power. It's a competition between China and most of the rest of the world over the rules that underlie the current system.”

Friedman began the event with his views on strategic discipline as it pertains to China and Russia. At the strategic level, a major challenge in the next decade is “strategic discipline.” Strategic discipline calls for the U.S. to be prudent and not be drawn into operations —covert or indirect— elsewhere. “Our ability to estimate the enemy is poor, and we play the ‘worst case scenario.’ The problem the United States faces is strategic discipline to decline combat where risks and costs are too high,” according to Friedman. “The Chinese have no direct attack possibility, but they will take action indirectly, and the United States must act very, very prudently not to get caught up in those kinds of wars.” Traditional Army threat paradigms may not be sufficient for competition, meaning, the U.S. Army could be drawn into unanticipated escalation as a result of China’s activities during the competition phase.

Mattiacci sees the next decade from a different perspective as she focused on the Strategic/nation-state and Non-state level by looking at the need to “seize your own narrative” utilizing social media and the ability to tell stories. She highlighted three trends in competition: the responsibility to protect, increasing public support, and the growth of social media.

According to Mattiacci, "Stories have an influence on foreign actors. When my co-author and I crunched the numbers on Libya and the rebels' efforts to reach out to foreign audiences through social media, we find a statistically significant positive impact of those tweets on U.S. behavior. Those tweets were able to increase cooperation on the part of the United States towards the rebels and decrease cooperation towards the government.” Adversaries seek to shape public opinion and influence decisions through targeted information operations campaigns, often relying on weaponized social media. Those that control information and shape the narrative will have the ability to weaponize information. This information is pushed to social media and other forms of media that people access every day.

Edwards highlighted tactical trends with strategic implications and the need to be more agile. These are the things we are taking for granted daily, the internet of things, and how separately they may seem harmless but bringing them together and manipulating them for other purposes can bring great harm. These systems, which may be increasingly used by law enforcement, can be altered and used in a way that makes us more vulnerable and the mal actor can deny us the ability to ‘see’ whom to counter. Additionally, he focused on our vulnerability associated with the use of Unmanned Aerial Systems (UAS), Artificial Intelligence (AI), and Internet of Things (IoT). According to Edwards, “You can influence and impact American society just by the things in our home.”

Within these different technical spaces, both China and Russia are accumulating advantages they hope will dull traditional U.S. combat advantages and the tenets described in Multi Domain Operations. However, both nations remain vulnerable and dependent on U.S. “Our adversaries don't necessarily have to attack us through the front door. Now you can impact and assault the American society by altering things by attacking through your television or attacking through the ability of a drone or an autonomous vehicle,” said Edwards.

Cooper spoke about the need for the U.S. to adopt more of a denial strategy, and, instead of focusing on expensive power projection, shift away from it and focus on working with our allies and partners.

“The U.S. is better than anyone in the world at power projection. The U.S. Army does it every day across the world, but the price of projecting power has gone up.” Denial is the ability to affect somewhere without being physically present. “China's military has invested huge sums in these kinds of capabilities (e.g., cheaper A2/AD), and their threat ring keeps getting expanded and the U.S. is getting pushed back. It is expensive to keep projecting power,” according to Cooper.

Cooper stated, “I think over the next decade, we shift the way we think about the U.S. military and about the work we do with allies and partners and adopt a much more denial focus strategy. It's not the one we would like to do if we had a hundred percent of the resources to do everything we wanted, but in a world where we have more constrained resources, this is probably the strategy that I think will make the most sense over the next 10 or 20 years.”

The lines between competition and conflict continue to blur, making non-kinetic actions even more important. The U.S. must consider the cost of projecting power across the globe relative to the gross domestic product decline.

Meisel showcased research and trends that pinpoint the need for the U.S. to out innovate and outgrow the problem and how the U.S. Army needs to “get comfortable with contestation and get comfortable with collaboration.” As researchers predict the timeframe for a shift in global power based on various factors, the data shows China and the U.S. swapping positions by the end of the decade. Meisel said. “The whole partner, multilateral approach moving forward, is going to rely largely on the U.S. maintaining its positive reputation and goodwill around the world, and I'm worried we won't do that.”

Meisel stated, “If the U.S. can have above-average economic growth, say two percentage points higher per year than expected, that would put us at three and a half maybe four percent then it's possible to delay the power transition with China until about a decade or a little over a decade from now. That buys time to adjust strategies and pivot there— if combined with China's growth being lower than expected- will it get old before it gets rich? — then perhaps a power transition doesn't occur at all before mid-century.”

The panelists took us from what peer competition and conflict could look like with China from the perspective of their strategic options, to revolutionaries and the power of social media and communications to mobilize and contest, and the emerging threats to the homeland and to our citizens. Both China and Russia remain vulnerable and dependent on U.S. innovations, as well as the challenges of incorporating these technologies into their own doctrine, training, and cultures.

Previous Mad Scientist Initiative events have focused on future learning, bioengineering, disruptive technologies, megacities, and dense urban areas and identifying other opportunities for further assessment and experimentation.

More information about the Mad Scientist Initiative can be found at https://madsciblog.tradoc.army.mil/

Social Sharing