RESEARCH TRIANGLE PARK, N.C. -- Army-funded researchers discovered how to make materials capable of self-propulsion, allowing materials to move without motors or hands.

Researchers at the University of Massachusetts Amherst discovered how to make materials that snap and reset themselves, only relying upon energy flow from their environment. This research, published in Nature Materials and funded by the U.S. Army, could enable future military robots to move from their own energy.

“This work is part of a larger multi-disciplinary effort that seeks to understand biological and engineered impulsive systems that will lay the foundations for scalable methods for generating forces for mechanical action and energy storing structures and materials,” said Dr. Ralph Anthenien, branch chief, Army Research Office, an element of the U.S. Army Combat Capabilities Development Command, now known as DEVCOM, Army Research Laboratory. “The work will have myriad possible future applications in actuation and motive systems for the Army and DOD.”

Researchers uncovered the physics during a mundane experiment that involved watching a gel strip dry. The researchers observed that when the long, elastic gel strip lost internal liquid due to evaporation, the strip moved. Most movements were slow, but every so often, they sped up.

These faster movements were snap instabilities that continued to occur as the liquid evaporated further. Additional studies revealed that the shape of the material mattered, and that the strips could reset themselves to continue their movements.

“Many plants and animals, especially small ones, use special parts that act like springs and latches to help them move really fast, much faster than animals with muscles alone,” said Dr. Al Crosby, a professor of polymer science and engineering in the College of Natural Sciences, UMass Amherst. “Plants like the Venus flytraps are good examples of this kind of movement, as are grasshoppers and trap-jaw ants in the animal world.”

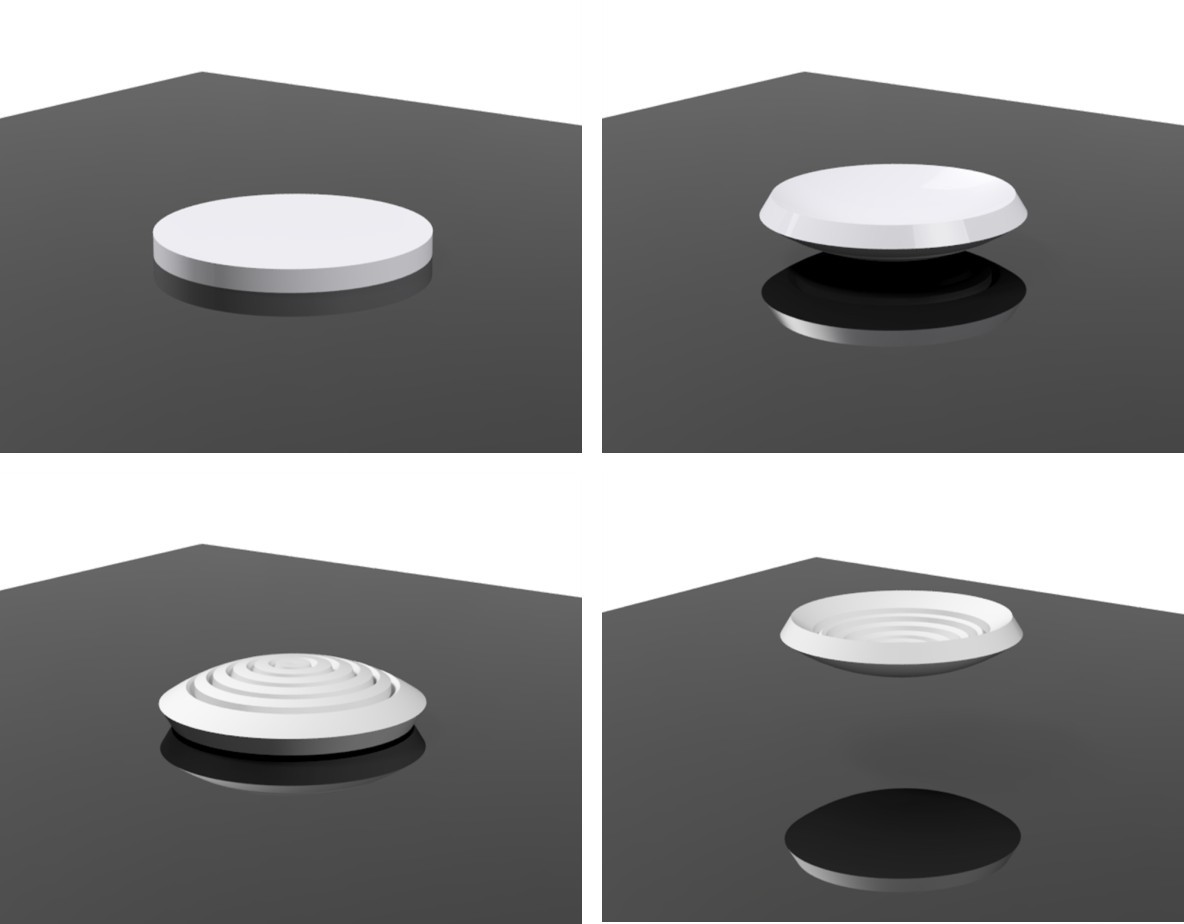

Snap instabilities are one way that nature combines a spring and a latch and are increasingly used to create fast movements in small robots and other devices as well as toys like rubber poppers.

“However, most of these snapping devices need a motor or a human hand to keep moving,” Crosby said. “With this discovery, there could be various applications that won’t require batteries or motors to fuel movement.”

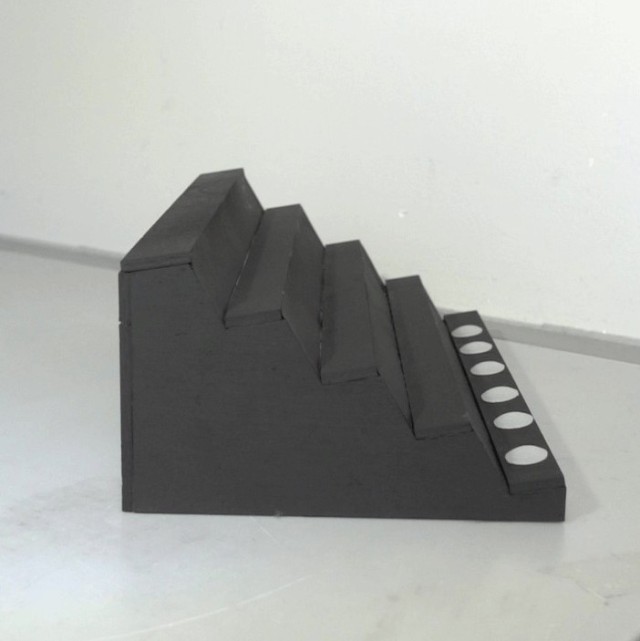

After learning the essential physics from the drying strips, the team experimented with different shapes to find the ones most likely to react in expected ways, and that would move repeatedly without any motors or hands resetting them. The team even showed that the reshaped strips could do work, such as climb a set of stairs on their own.

“These lessons demonstrate how materials can generate powerful movement by harnessing interactions with their environment, such as through evaporation, and they are important for designing new robots, especially at small sizes where it’s difficult to have motors, batteries, or other energy sources,” Crosby said.

The research team is coordinating with DEVCOM Army Research Laboratory to transfer and transition this knowledge into future Army systems.

Visit the laboratory's Media Center to discover more Army science and technology stories

DEVCOM Army Research Laboratory is an element of the U.S. Army Combat Capabilities Development Command. As the Army’s corporate research laboratory, ARL is operationalizing science to achieve transformational overmatch. Through collaboration across the command’s core technical competencies, DEVCOM leads in the discovery, development and delivery of the technology-based capabilities required to make Soldiers more successful at winning the nation’s wars and come home safely. DEVCOM is a major subordinate command of the Army Futures Command.

Social Sharing