As national shortages of personal protective equipment (PPE) left thousands of frontline medical personnel and emergency room staff exposed to a deadly novel coronavirus, commanders across the Army’s major commands identified a capability within their formations to fulfill the growing demand for life-saving PPE. Armed with sewing and 3D printing capability, U.S. Army parachute riggers were identified as uniquely postured to address the vacuous supply chain. Relying on ‘rigger ingenuity,’ aerial delivery facilities rushed to action to develop prototypes, mass-manufacture, inspect, and distribute protective masks and face shields.

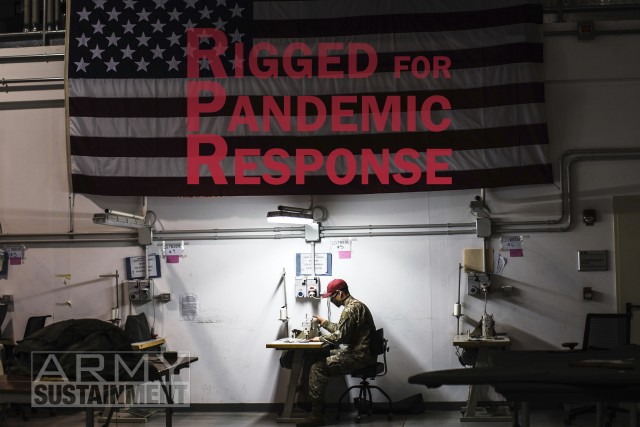

An aerial delivery facility's mission is to provide personnel and cargo parachute packing, aerial delivery resupply, and air items maintenance to support their organization's airborne mission (aligned across the warfighter functions). In a matter of days, riggers across the U.S. and Germany traded parachute nylon for fabric that met the Center for Disease Control (CDC) guidelines to mirror the N95 mask, which uses nonporous cotton material with a reusable filter to protect against COVID-19, and traded their packing tools for 3D printers to shift from parachute repair and maintenance to the production of masks, gowns, and face shields. Under the oversight from their Corps Level Surgeons Office and utilizing light-duty sewing machine equipment within their military table of organization and equipment, following the common table of allowances (CTA-50-909), the riggers synchronized their sewing machines to sew 7-11 stitches per inch without damaging the material or allowing for any open pinholes on the mask or keepers (straps around the ears). The riggers also changed the type of thread and materials used to meet medical guidelines. Some of the materials used included post-exchange bedsheets, Army uniform surplus t-shirts, and cotton blends. 647th Quartermaster Company, Fort Bragg, North Carolina, used donated fabrics from North Carolina State University Wilson College of Textiles. Down the street, 188th Brigade Support Battalion utilized 3D printers to produce protective face shields.

With COVID-19 restricting airborne operations, the riggers aimed for an original goal to produce 600 cotton masks a week. An overwhelming sense of duty and friendly competition among the teams fueled an output of 600 masks a day. Many of these masks and face shields were distributed to units and essential personnel across Fort Bragg—the most populated military installation in the country and home of the 82nd Airborne Division and Special Operations Forces.

The masks themselves are simple: cotton and miscellaneous fabric coverings for the mouth and nose fastened together around the head. The masks are not intended to be stand-ins for the Federal Drug Administration-recommended N95 masks. In dire conditions, like those experienced at Madigan Army Medical Center, Joint Base Lewis-McChord (JBLM), Washington, PPE's additional supplies were a force multiplier to protect essential personnel. Nearby, Seattle was the epicenter for the first U.S. outbreak of COVID-19 and the initial demand signal. Army parachute riggers immediately began to innovate and adjust, developing several prototypes until final approval was obtained from the unit’s Surgeons Office, to meet the surge. Working together, the entire rigger community operated as one entity to meet the mission requirements.

Group Support Battalion, 1st Special Forces Group (Airborne), JBLM, employed feedback from medical employees to refine their prototypes for reusable masks, face shields, and surgical masks. As a result, Madigan Army Medical Center and its regional partners continued to receive improved products from the riggers. Each iteration and lesson learned generated practical improvements. Lessons learned also included navigating new processes for material funding requirements, approvals from the brigade surgeon and Army Medical Command, and developing a task distribution matrix. Considerations for the distribution matrix include:

- Location of production

- Needs versus wants

- Safeguarding Soldiers and their Families

- Mask quality vs. mask quantity

- Approval process and acquisition in each mask-making process

- Wear and tear on light duty sewing machines

- How to transition from mask fabrication to real world support requirements

- Shift supervision and safety of production teams from COVID-19

- Managing high risk (for COVID- 19 complications) team members

Through these efforts and comprehensive medical research, a standardized prototype was created, a template was designed, and guidance was developed and disseminated to the force. Countless rigger sheds across the Department of Defense adopted and employed these practices to manufacture masks and face shields.

For military installations overseas, producing face masks was not just about protecting personnel and their dependents. It was an opportunity for parachute riggers to engage in good-neighbor diplomacy. At Rhine Ordnance Barracks, Kaiserslautern, Germany, riggers assigned to 5th Quartermaster Theater Aerial Delivery Company (TADC) produced masks for the 1,300 civilians working at Theater Logistics Support Center-Europe. Thinking outside of the box to meet Army guidelines, the riggers procured subdued-colored bed sheets at the Ramstein and Baumholder exchange stores. Working as a well-oiled machine, 14 Soldiers manned alternating day shifts at Rhine Ordnance Barracks: five riggers operated sewing machines while two Soldiers stenciled and cut fabric. One mask took about ten minutes for the team to produce.

These masks support mechanics, truck drivers, and craftsmen of the mostly German workforce. This assistance proved critical, given that mandated quarantines affecting local fabric manufacturers resulted in a scarce supply of face masks in the area. The opportunity to serve the health needs of the local workforce not only protected the installation but demonstrated American investment in the German communities that host US forces.

Production Results

Stateside, riggers assigned to the aerial delivery facility at 19th Special Forces Group (Airborne) (19th SFG-A), Camp Williams, Utah, produced 7,015 cloth masks and distributed an additional 6,200 masks to Utah National Guard (UTNG) members throughout the state. These masks were used by UTNG Soldiers while conducting a regular drill, and annual and pre-mobilization training events. The UTNG riggers even sent 200 masks with 19th SFG-A Soldiers charged with safeguarding Washington, D.C., during the civil unrest in the capital region. UTNG riggers spent between 1,000 and 1,200 hours of precise, attention-to-detail fabrication to safeguard their team members’ lives during the call to duty.

In North Carolina, National Guard riggers assigned to 403rd Quartermaster Rigger Support Team (403rd QM RST) shared similar sentiments pertaining to their support mission. The eight Soldiers assigned to 403rd QM RST broke into two shifts of four Soldiers. To maintain production, they were broken into two shifts maintaining day/night shift integrity and operating as isolated "bubbles." That way, if one team would be down with COVID-19, there was another team to continue the mission. Soldiers were leading a critical mission to the state that loss of personnel due to COVID-19 was not an option. In 31 days, they worked an estimated 60-hours a week to manufacture 4,401 masks in two distinct models for individual comfort (straps and elastic). As the unit progressed with production, and received feedback from the users in the field, there was a clear understanding that a variety of factors—pertaining to visibility, comfort and wearability, and type of job—were going to affect the individual decision to use adequately or not use the face mask. Incorporating this feedback, the riggers developed masks that tied at the back of the head and masks that affix to the head with elastic bands behind the ears. The two designs offered Soldiers the most comfortable alternatives to use the masks.

The masks were then distributed across the state amongst NCNG members directly engaged in health-care, logistical distribution, farming and cropping, food bank distribution support, and many other missions of support to civil authority aimed at sustaining North Carolinians. When asked about their driving force to push through the long hours, Staff Sgt. Betuel Monje, noncommissioned officer-in-charge for the facility said, “If [guardsmen are] not protected then how can they serve their com-munities? And how can they help those around them that are also in harm’s way by this virus? We are here for them; to protect the protectors.”

Elsewhere, riggers assigned to 4th Quartermaster TADC, Joint Base Elmendorf-Richardson (JBER-AK), Alaska, completed their 100% aerial delivery care of supplies in storage (COSIS) mission at Sagami Army Depot, Japan, before transitioning to making cloth masks in support of U.S. Army Japan. An urgent need for increased production in the region as a result of the civilian manufacturer’s inability to meet the demand for medical masks necessitated that U.S. Army Pacific (USARPAC) augment 4h QM’s mission in theater. Al-though their home station is in Alaska, Chief Warrant Officer 2 Mervin Terre utilized two days remaining on the COSIS mission to produce masks for USARPAC units stationed in Japan. The masks were produced per the schematics provided from 1st Special Forces Group, but required some augmentation due to material availability, shipping, and board-acceptance requirements to support the local populace. The COSIS team immediately began developing their plans for mask production and training four local Japanese civilian employees to maintain production continuity after the Alaska-based parachute riggers departed the region.

Army parachute riggers across the total force delivered 97,150 masks, 793 face shields, 3,200 disposable pediatric face coverings, and 300 isolation gowns. Additionally, some commands maintain up to 6,000 masks to issue, as required, during sustained operations.

Over 12,000 military and 6,000 civilian organizations were provided PPE produced by Army parachute riggers. At least 26 Active duty, Reserve, and National Guard parachute rigger facilities worked over 7,302 hours in response to the call for help. The well-being and protection of communities, fellow Soldiers, and emergency response personnel became the constant fuel driving the long hours endured.

--------------------

Chief Warrant Officer 3 Viviana Y. Paredes serves as unit commander and airdrop systems technician for 403rd Quartermaster Rigger Support Team, North Carolina Army National Guard. She is also a Department of the Army Civilian serving as the safety director for 35th Signal Brigade (Theater Tactical), Fort Gordon, Georgia. Paredes has served as an airdrop systems technician and a parachute rigger in units within U.S. Forces Command, U.S. Special Operations Command, and Army Test and Evaluation Command. She has served two deployments in Kuwait and Afghanistan. This article was written while attending her last semester at North Carolina A&T State University, in pursuit of a Bachelor of Science in Environmental Health and Safety. She is simultaneously attending Warrant Officer Intermediate Level Education Course at Fort Rucker, Alabama. She is a graduate of Warrant Officer Basic and Advanced Courses.

--------------------

This article was published in the October-December 2020 issue of Army Sustainment.

RELATED LINKS

The Current issue of Army Sustainment in pdf format

Current Army Sustainment Online Articles

Social Sharing