In November 2018, the Camp Fire decimated the rural town of Paradise, California, becoming the state's most destructive and deadliest wildfire ever. The windswept wildfire razed more than 14,000 residences, and at least 86 people were killed.

While Sacramento District's official involvement following the Camp Fire has been minimal, that hasn't prevented district employees from getting involved.

Joanne Goodsell was recently hired as a Cultural Resources Specialist for the Corps. She is also an archaeologist, and wanted to find a way to use her skill-set to help victims of the fire. She would have been motivated to help regardless of where the fire took place, but this one hit home - literally. Goodsell grew up in Paradise.

"It was personal. I had wanted to do something to help, but there's not much you really can do outside of donating. But sometimes you want to help firsthand, to find a way to do more," said Goodsell.

She did donate money, but was still looking to find how she could do more. That's when she came across a Facebook post leading her to a group called the Institute for Canine Forensics.

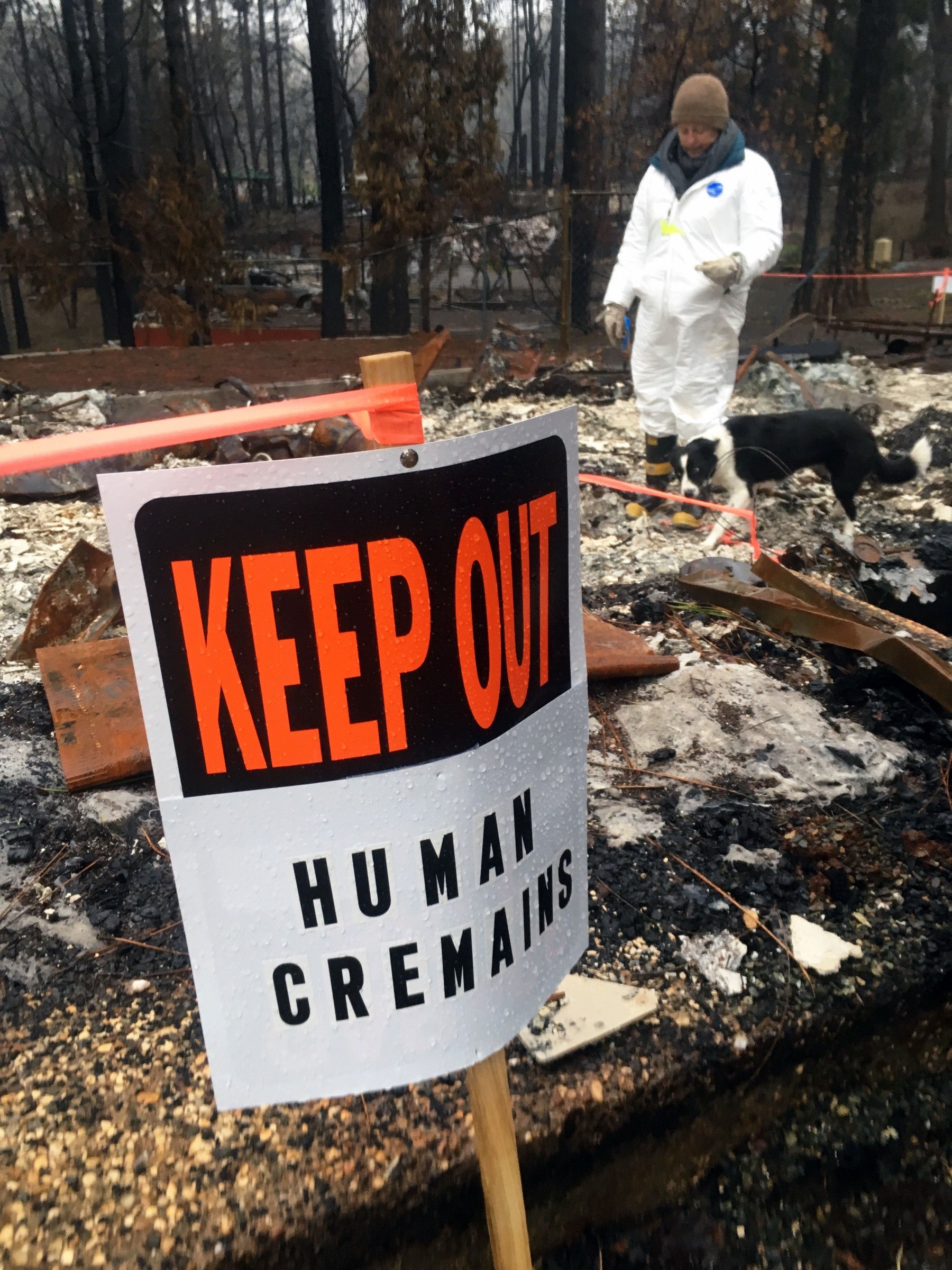

The ICF, in coordination with two Northern California archaeological consulting firms, was asking for archaeologists to come out and help with the unfortunate task of trying to find people's ashes; not of those who perished in the fires, but the ashes (also called cremains) of previously deceased and cremated loved ones that were now intermingled with the ashes and debris of their burned out homes.

"A friend had posted a link where the ICF was asking for archeologists to help with the recovery efforts," said Goodsell. "So I got in contact with them and found this was a good fit for my skill set as an archaeologist."

Goodsell's involvement soon inspired other archaeologists in her section at the Corps to volunteer as well. Joe Griffin, Chief of the Cultural, Recreational, and Social Assessment Section soon got involved, as did archaeologists Hope Schear and Geneva Kraus.

Finding ashes among ashes would seem an impossible task, but the ICF brought in dogs that are specifically trained to locate human cremains. After a client has requested service, an ICF handler speaks to the client to determine the approximate location of the cremains and what kind of container they were in. The dogs then sniff through the debris field and either sit or lay down when they find a scent. From there it's up to the teams of archaeologists.

Nature's chemical reactions also provide some help in the archeologists' searches. First, the texture of the human ashes are different from ashes of say, burned drywall or wood. Second, when the cremains burn a second time, they turn a different color than the typical gray or white ash surrounding them, making them easier to see.

Dressed in protective clothing, the archeologists would determine a search area, set up a perimeter and begin excavating down to ground level, removing layers of ash and debris as they worked toward where they believed the cremains to be.

Most often, they eventually found the cremains on the ground, surrounded or mixed in with other ash and debris. Original ceramic containers almost never survived the fire, and metal urns melted. It was helpful that sometimes the searchers also found the original metal medallion that stays with a cremated body, making recognition of the human ashes a bit easier.

"One set of cremains were in a fireproof safe, and even it burned, but we still found some cremains in there," said Goodsell. "Our highest recovery rates were often for cremains that were in the original containers and had been sitting on the floor of a closet."

The loss of a loved one's ashes can add a sense of guilt to the already heavy burden of losing a home, especially for those who had yet to fulfill a promise to spread a loved one's cremains as requested in person or in a will. Fortunately, Goodsell said they had close to a 70 percent success rate in recovering and returning entire cremains and medallions.

"Finding and returning the cremains meant a great deal to these family members," said Goodsell. "Even if it was a small, token amount, people were very, very grateful."

Social Sharing