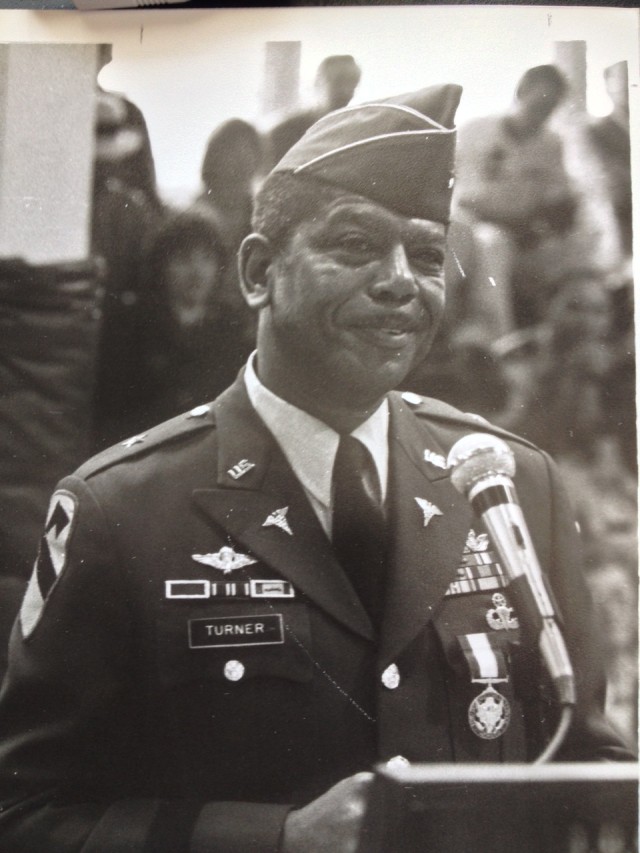

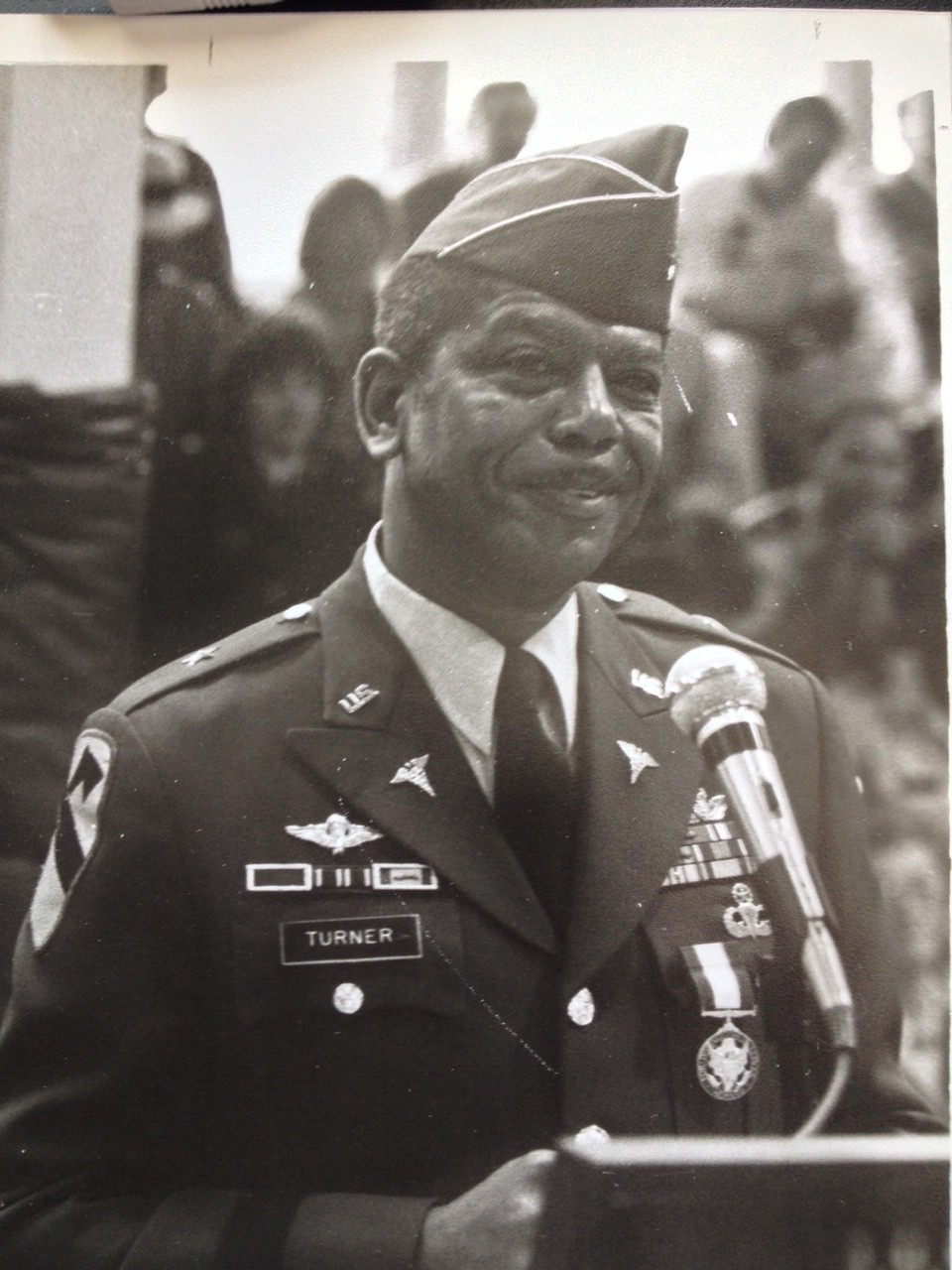

Even before the marches led by Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., Guthrie Turner Jr. set about in his own way to break down the color barriers in the Army.

While Turner commissioned as an Army physician five years after President Harry Truman abolished racial discrimination in the military in 1948, it would take throughout the 1950s before segregation ended in the Army.

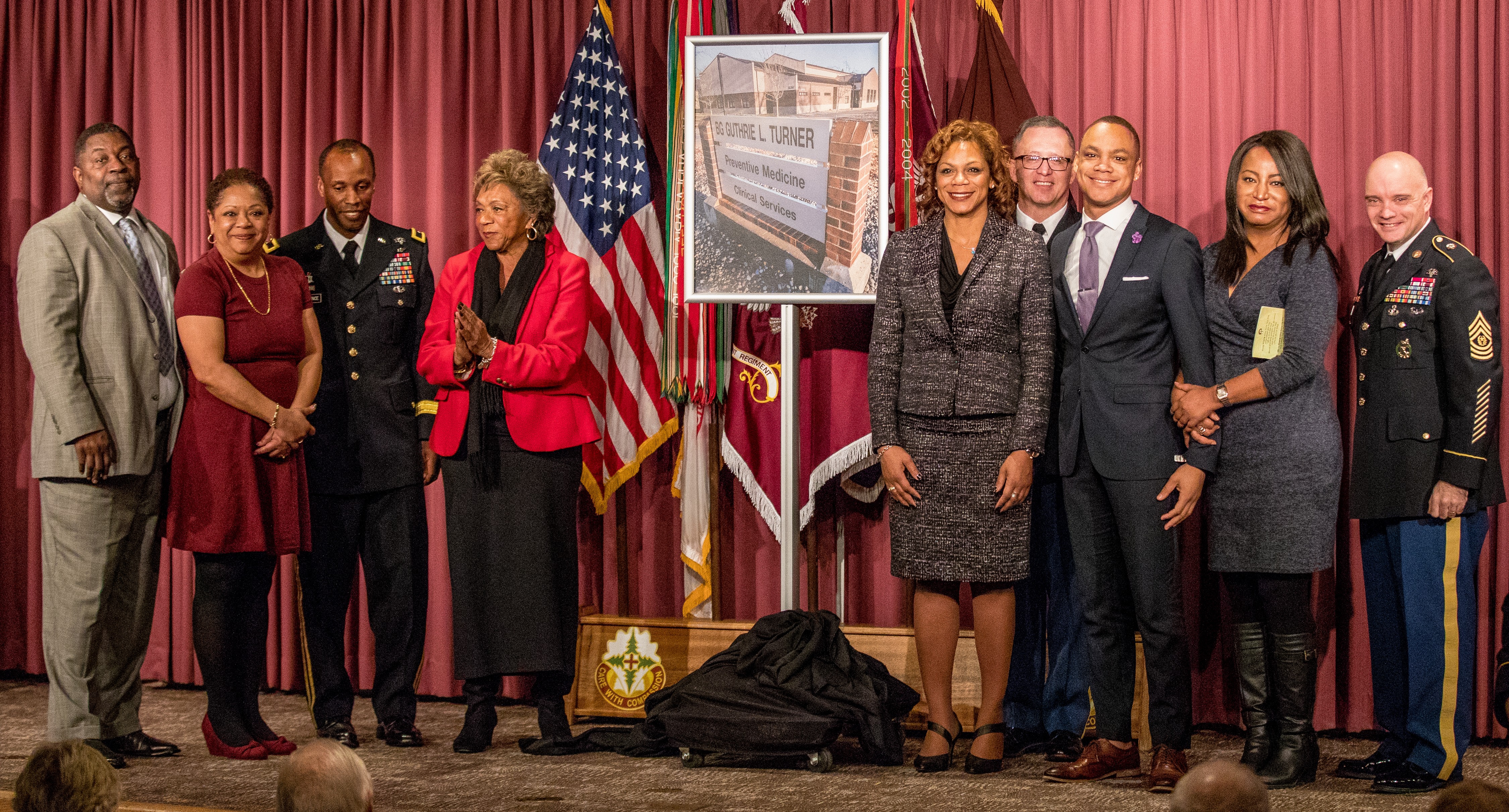

Turner's dedication to being a true leader, an exceptional physician and a trailblazer in Army Medicine led Madigan Army Medical Center to dedicate the Brig. Gen. Guthrie Turner Junior Preventive Medicine Clinical Services Building here on Feb. 2.

"He became the first black doctor to be promoted to general officer on active duty," said his wife, Ella Turner; they were married for 57 years and had raised four children together before he passed away in 2014.

The two met in North Carolina, when Ella was a freshman in college and Turner was going to be stationed at Fort Bragg, N.C., for airborne training. Before they wed, he asked Ella if she could be a military wife; she said yes. While military life has its own stresses, from the first duty station the Turners also carried the weight of racism.

"When we started out at Fort Bragg … it was actually Jim Crow time. There were very few black officers," said Ella. "The Army was segregated at that time -- everywhere, every base."

When they traveled to other locations the Turner family had to drive straight through when they encountered "No Blacks" signs at hotels and restrooms.

"We were not happy about it, I can tell you that; we were not happy at all. But there was nothing you can do. What can you do? We had to wait and let that battle be won by Martin Luther King and others. We had to just do what we were told and get from point A to point B," she said.

Inside the military gates, Turner encountered prejudice from his commissioning day (he commissioned as a first lieutenant while others in his year group commissioned as captains) to being denied a residency (he served at a community hospital instead) to just plain having to work harder to get equal opportunities as his white peers. It was his inner strength instilled by his parents during the Depression days that led Turner to thrive.

"In my eyes, General Turner is the Jackie Robinson of military medicine," said Brig. Gen. Bertram Providence, commanding general of the Regional Health Command-Pacific, referring to the first black baseball player to play on an integrated team in the 1940s. He called Turner a trailblazer as well.

"Guthrie had to fight for everything; he had to be the best of the best for everything," said Ella. "He went through some dark days, but he wasn't going to give up -- he just kept fighting and fighting and fighting."

That fight and determination led to Turner graduating from high school at the age of 15, earning his doctorate of medicine at Howard University, attending Harvard University for his master's degree, and deciding that in addition to being a military doctor he'd also be a master parachutist and a pilot.

"He knew that somebody had to do it, and he set his mind to breaking those barriers," Ella said. "I think that's why Guthrie worked so hard in so many areas. He wanted to open up areas for other black Soldiers; he wanted them to fly, he wanted them to go into any area that they felt confident and to work hard, because it was hard work that did it for him. Just constantly working all the time, because otherwise he wouldn't have made it."

Throughout it all, as the Army desegregated and he climbed the ranks, Turner's reputation as a strong leader and mentor built.

"Dr. Turner was very exceptional, a good man and he was a very, very good leader," said retired Sgt. 1st Class William Clark. "He was a Soldier's commander."

Former medevac pilot Art Jacobs shared the story of a mission in the jungles of Vietnam in which his aircraft was shot down.

"My crew was lifting me up into the rescue bird because I had been shot, and a hand reached out and I looked up and it was Col. Turner. It was just kind of amazing because he was the doctor and the battalion commander and had no business going out there on such a mission, but there he was, and it's something I'll never forget," said Jacobs, as emotions weighed down his words.

After that tour, Turner made history again when he became the first African American hospital commander at Fort Wolters, Texas, in 1969. Eleven years later, he pinned on general and moved for the final time to command Madigan. He left his own mark here as a propelling force behind the construction of the current Madigan hospital.

With the memorialization of the prevention medicine building, Ella hopes young doctors will learn about the building's namesake and become inspired by him.

"They're going to say if he could do it, I can do it, which would mean a lot to him," said Ella.

Social Sharing