NATICK, Mass. (Feb. 22, 2017) -- Mention the Occupational Physical Assessment Test, or OPAT, to Soldiers, and most will know about the battery of four physical performance tests that, starting in 2017, the Army administers to all recruits to assess their physical performance capabilities to determine if they should be allowed to join the Army.

The implementation of the OPAT is a major change in how the Army will assess potential recruits. It will identify individuals who have the capabilities to perform some of the Army's most physically demanding military occupational specialties, or MOS's, such as those in the Combat Arms, as well as individuals who are not yet physically prepared to start training.

What the world did not know about was the science and effort involved in developing the OPAT.

During an award ceremony on Jan. 20 in Fort Eustis, Virginia, at the U.S. Army Center for Initial Military Training, or CIMT, Maj. Gen. Anthony Funkhouser, commanding general of CIMT, recognized researchers from the U.S. Army Research Institute of Environmental Medicine, or USARIEM, for their contributions to the OPAT. CIMT is part of Training and Doctrine Command, or TRADOC.

Marilyn Sharp, a research health exercise scientist and the principal investigator of the OPAT study, was awarded the Commander's Award for Civilian Service. Dr. Jan Redmond and Dr. Stephen Foulis, both research physiologists and associate investigators on the study, each received the Achievement Medal for Civilian Service.

"The purpose of the OPAT is for a recruiter to test a Soldier easily and quickly to determine whether they are physically ready to be trained for a MOS," said Sharp, of USARIEM's Military Performance Division, or MPD. "What USARIEM researchers did was get it down to the essential physical capabilities that a Soldier needs to be trainable for a given MOS."

Back in 2013, USARIEM researchers began working with TRADOC in a three-year research effort known as the Physical Demands Study. USARIEM researchers traveled thousands of miles to different Army bases, spoke with hundreds of Soldiers at all levels, collected physiological performance data and conducted several stages of testing with the goal of developing the physical tasks in what recruits know today as the OPAT: the standing long jump, seated power throw, strength deadlift and interval aerobic run.

The effort was part of the comprehensive TRADOC "Soldier 2020" initiative, which would help set the standards necessary for Soldiers--male and female--to perform combat MOS's, including those in armor, infantry, field artillery and combat engineering. The goal of Soldier 2020 was to better match an individual's physical capabilities to the requirements of a specific MOS.

"TRADOC wanted a physical test, or a battery of tests, to accurately assess a recruit's physical potential to perform physically demanding military tasks," Sharp said. "By using this predictive test, they would be able to assign the right Soldier to the right job."

The first step in developing the OPAT was to identify the physically demanding tasks of the Combat Arms MOS's. The OPAT tasks were developed from an analysis of 32 physically demanding tasks that Soldiers must perform.

Where did these initial 32 tasks originate?

"TRADOC consulted with senior subject matter experts from the Army Branch Offices for infantry, field artillery, armor and combat engineering to compile a list of the critical physically demanding tasks each performed," Sharp said. "Some of the tasks were common to several MOS's, while others were specific to an MOS. The list was socialized among leaders in the deployed force."

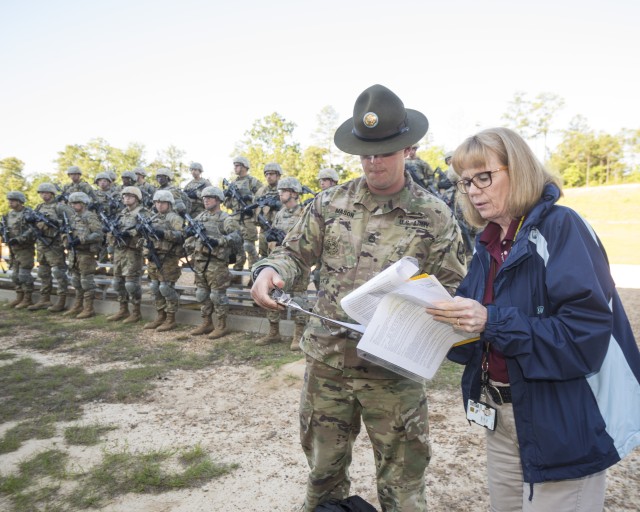

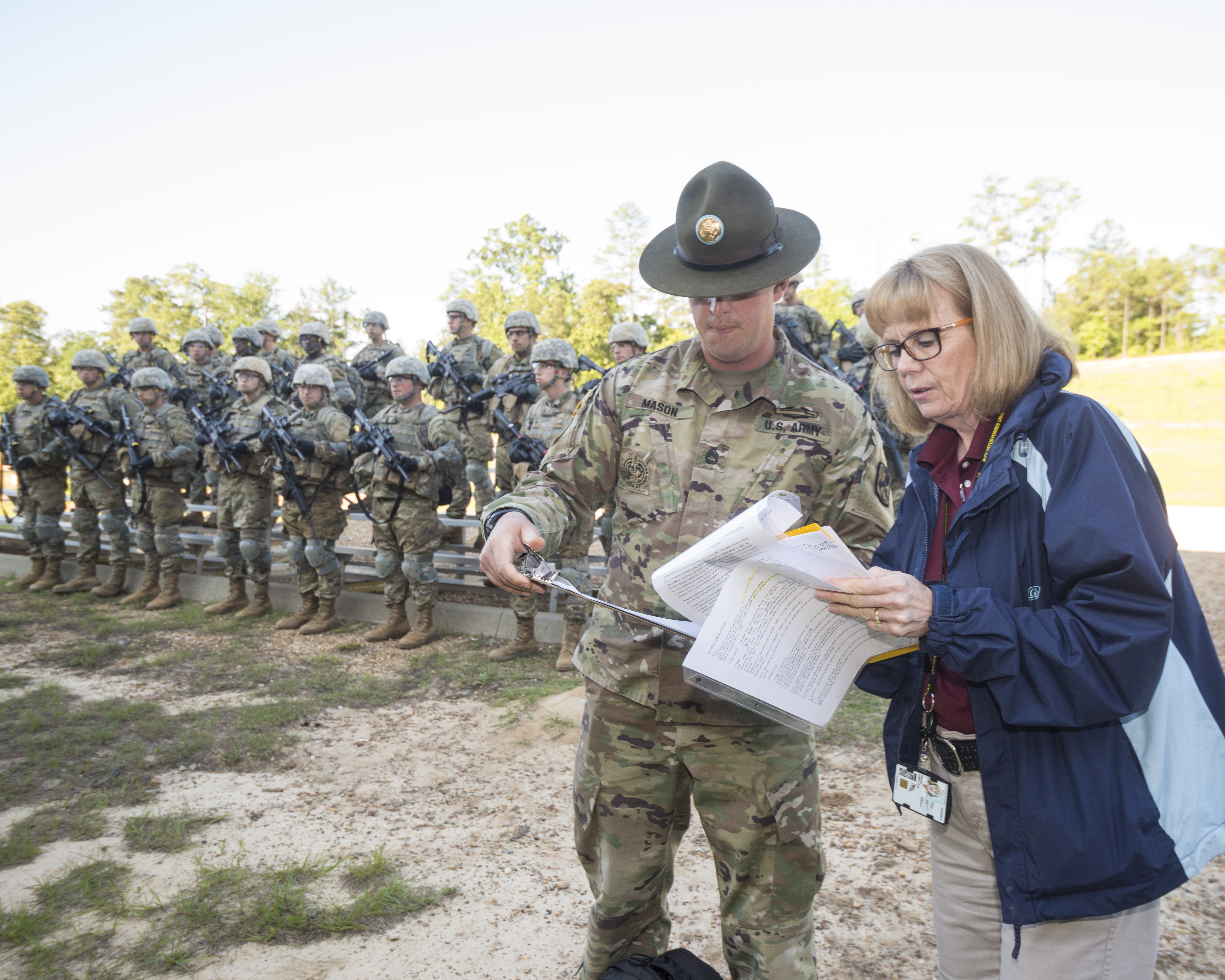

TRADOC conducted a field training exercise to verify the accuracy of the tasks, conditions and standards across the operational force by having more than 500 Soldiers from eight brigades--heavy and light units--throughout five installations perform the 32 tasks. For a successful verification, 90 percent of the Soldiers should be able to complete the tasks to standard. TRADOC subject matter experts examined the data and revised the task standards if needed. While TRADOC conducted the field training exercise, USARIEM researchers were able to observe the Soldiers in action.

"We were able to observe the Soldiers performing these tasks and learned a lot about how tasks were performed, what equipment Soldiers needed and how long tasks typically took," Sharp said. "Some task standards and conditions had to be re-examined because more than 10 percent of the Soldiers could not perform them to standard."

That was when TRADOC gave USARIEM the green light to administer the first phase of the Physical Demands Study. They conducted face-to-face focus group interviews with junior and senior enlisted Soldiers to learn how accurately these 32 tasks matched what Soldiers did in the field.

Then the researchers dug a little deeper. From Fort Hood, to Fort Bliss, to Fort Stewart and more, USARIEM researchers traveled to different Army posts for about a year to test male and female Soldiers performing the 32 tasks. Sharp and her team wanted to gather physiological data.

"We wanted to see how difficult these tasks really were," Sharp said. "Along with asking volunteers how hard they found the tasks and observing how many volunteers were able to complete them, we measured their time to completion, energy cost, heart rate, respiration and oxygen consumption."

The researchers used the physiological data to narrow down the 32-item list to the eight most physically demanding tasks. After gaining consensus on the eight tasks from the Army Branch Offices, USARIEM researchers developed task simulations to assess the unique physical requirements of each task.

"The task simulations were simplified versions of the critically physically demanding tasks," Sharp said. "They were modified to allow the tasks to be performed individually, provide a range of physical scores instead of just a pass-fail rate and ensure reproducible and reliable results."

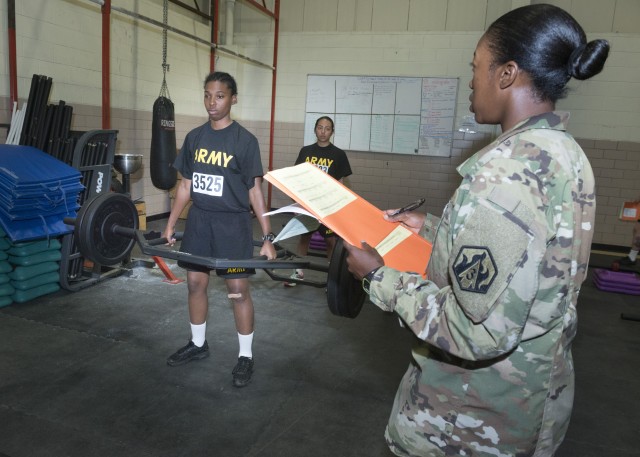

From 2014 to 2015, 877 fully trained active-duty men and women completed both the task simulations and a series of simple predictor tests, which to civilians, look similar to fitness tests performed in gym class.

The goal was to determine which predictor tests successfully predicted performance on the task simulations. When USARIEM presented their findings to TRADOC, the researchers had distilled the criteria to the four OPAT tasks. According to Sharp, these tasks were shown to be statistically significant in predicting Soldier task performance while remaining gender, age and body-size neutral.

USARIEM was then tasked by TRADOC's CIMT in November 2015 to establish the validity of using the OPAT to test new, untrained recruits. Redmond, also from MPD, indicated that the testing of recruits went extremely well, largely due to the experience the research team had acquired during the OPAT testing of active-duty Soldiers.

"By the time we got to the OPAT, we learned a tremendous amount about how to make the testing procedures go quickly and smoothly," Redmond said. "During the task simulations, for example, rather than asking a Soldier to build a bunker, we determined that the action of lifting and carrying sandbags was more physically demanding than filling the bags with sand. For the task simulation, Soldiers carried prefilled sandbags a specified distance."

The research effort to validate the use of the OPAT over a period of time concluded in December 2016. About 100,000 recruits and thousands of cadets will take the OPAT starting this year, yet the research is never over. USARIEM will follow the volunteers during the first two years of their service to see if they are successful in their assigned MOS's after receiving OPAT results, or if they change their MOS's or leave the Army. TRADOC's CIMT will conduct surveillance continuously to see how accurately the OPAT assesses physical requirements for MOS's.

Developing the OPAT is regarded as a major achievement for the USARIEM researchers, and according to Sharp, it will help shape the future U.S. Army.

"The goal of the OPAT is to put the right Soldier in the right job," Sharp said. "Soldiers who pass the OPAT for their MOS should be trainable to be successful. One of the unintended benefits of the OPAT is that the Army may see a reduction in musculoskeletal injury and attrition rates during basic training, which would optimize Soldier readiness."

Social Sharing