WASHINGTON -- Hispanic men and women have bravely and eagerly served the United States since the early, desperate days of the Revolution, when it seemed like the Continental Army was fighting a losing battle against the might of Britain. They continued what for many was a personal fight for freedom in the Mexican-American and Spanish-American wars, and like other Americans, were bitterly divided during the Civil War. Some 4,000 went "over there" to Europe during World War I. Hispanic-Americans served in every theater during the Second World War, and participated in some of the most brutal fighting during Korea and Vietnam.

Historically, discrimination, racism and language barriers meant that many Hispanics were relegated to menial jobs or served in segregated units. A number of Mexican-American cavalry militias chased bandits and guarded trains and border crossings for the Union during the Civil War, for example. Later, the 65th Infantry Regiment -- the "Borinqueneers" -- from Puerto Rico served valiantly in both World War II and Korea. Congress recognized the unit with a Congressional Gold Medal in 2016.

One of their number, retired Master Sgt. Juan Negron, posthumously received the unit's first Medal of Honor in 2014 for his service in Korea. The award came after a Congressionally mandated review of Jewish- and Hispanic-American war records from World War II, Korea and Vietnam resulted in Medals of Honor for 24 veterans whose remarkable heroism had been overlooked, often due to prejudice. Of course, Hispanic Americans have been risking their lives above and beyond the call of duty since the medal's inception during the Civil War. Here are some of their stories.

CIVIL WAR

Corporal Joseph H. De Castro, an 18-year-old flag bearer from Company I, 19th Massachusetts Infantry, became the first Hispanic American to be awarded the Medal of Honor when he distinguished himself during Pickett's Charge at the battle of Gettysburg, July 3, 1863. As part of III Corps' 3rd Brigade, his unit helped defend Cemetery Ridge against the disastrous Confederate assault. De Castro attacked a Confederate flag bearer from the 19th Virginia Infantry Regiment with the staff from his own set of colors. De Castro became one of seven men from the 19th Massachusetts Inf. to be awarded the Medal of Honor, December 1, 1864. Castro continued to serve in the regular Army after the Civil War.

WORLD WAR I

When Pvt. David Barkley Cantu enlisted in the Army at 17 and deployed to France during World War I, he did so hiding a secret: His mother was Mexican-American, and he feared being kept from the front lines due to discrimination. Barkley even asked his mother not to use her maiden name in letters. November 9, 1918, Barkley's unit, Company A, 356th Infantry Regiment, 89th Infantry Division, surveyed the Meuse River in order to locate enemy positions. Barkley and another Soldier volunteered to swim across the river under fire to obtain intelligence and scout the German side of the river. As Barkley swam back to the Allies, however, he was seized with cramps and drowned. Barkley's family believed that fear of being discovered as a Mexican-American might have prompted him to volunteer for the dangerous mission. He was commended by Gen. John Pershing and posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor in 1919. He also received the French Croix de Guerre and the Italian Croce Merito de Guerra.

WORLD WAR II

In June 1942, Japanese forces invaded Alaska, first the Aleutian island of Kiska and then the island of Attu. The U.S. feared that the islands would be used as bases from which to launch aerial assaults against the West Coast, and soon began planning a response. Pvt. Joe P. Martinez, an automatic rifleman from New Mexico by way of Colorado, landed at Holtz Bay, Attu, the following year with Company K, 32nd Infantry Regiment, 7th Infantry Division to take back the island. After several days of heavy fighting in snow-covered mountains, the regiment became pinned down twice in an area known as Fish Hook Ridge, May 26, 1943. Both times, Martinez stood up and continued advancing in the face of heavy fire. His bravery inspired others to follow. Martinez silenced several enemy foxholes with automatic rifle fire before being shot in the head. He died of his wounds the following day and was posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor.

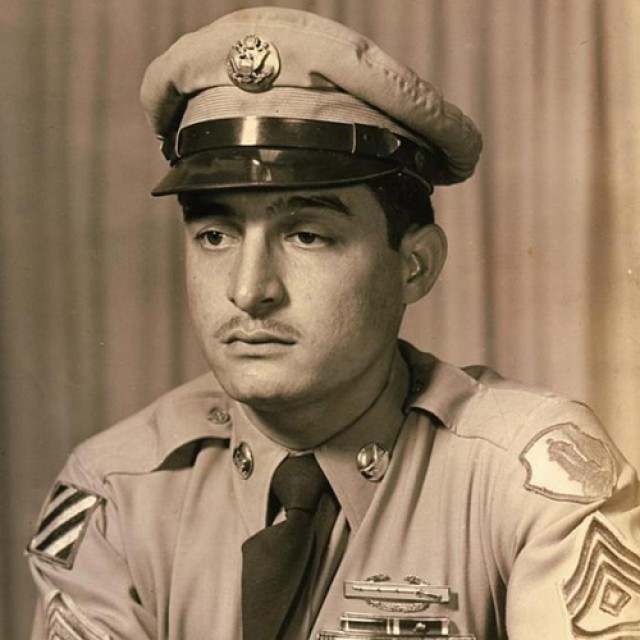

Staff Sgt. Lucian Adams enlisted in the Army in February 1943, after spending two years in a wartime factory building the same landing craft that would transport him to the beaches of southern France in August 1944 with the 30th Infantry Regiment, 3rd Infantry Division in Operation Anvil. Two and a half months later, Oct. 28, German troops blocked Adams' company in the Mortagne Forest near Saint-Dié, France. Adams charged forward, advancing from tree to tree while firing a Browning automatic rifle and dodging grenades and machine-gun fire that rained branches down on him. He came within 10 yards of the closest machine gun and killed the gunner with a hand grenade before turning his rifle on another enemy soldier. Adams continued to advance in the face of withering fire. When his one-man attack ended, he had killed nine Germans, captured two, eliminated three machine guns, cleared the woods and reopened the severed supply lines. "I'd seen all my buddies go down … calling for medics, and I didn't want to go down with any ammunition still on me, so I just kept firing," he told The Dallas Morning News in 1993. Adams received the Medal of Honor, April 22, 1945, at Nuremberg, Germany. Following the war, he went to work for the Department of Veterans Affairs in San Antonio.

Private Cleto Rodriguez was serving as an automatic rifleman with Company B, 148th Infantry Regiment, 37th Infantry Division when his unit attacked a heavily defended railroad station in the battle for Manila, Feb. 9, 1945. After intense enemy fire halted their platoon 100 yards from the station, Rodriguez and Pfc. John Reese charged the enemy soldiers, stopping at a house about 60 yards from the Japanese defenses. The two Americans killed about 80 enemy soldiers and wounded many more. Rodriguez charged the station, launching five grenades through the doorway. When they began to run low on ammunition, Rodriguez and Reese retreated, covering each other until Reese was mortally wounded. A few days later, Rodriguez single-handedly helped his unit advance in Manila when he killed six Japanese soldiers and destroyed another 20-mm gun. Both he and Reese received the Medal of Honor. Rodriguez eventually retired as a master sergeant.

Staff Sgt. Marcario Garcia, Sgt. Jose M. Lopez, Pfc. Jose F. Valdez, Pfc. Manuel Perez, Jr., Pfc. Silvestre S. Herrera, Staff Sgt. Ysmael R. Villegas, Pfc. David M. Gonzales, Pfc. Alejandro R. Renteria Ruiz, Staff Sgt. Rudolph B. Davila, Pvt. Pedro Cano, Pvt. Joe Gandara, Pfc. Salvador J. Lara and Staff Sgt. Manuel Mendoza also received Medals of Honor for valor above and beyond the call of duty during World War II.

KOREAN WAR

Then-Sgt. Juan E. Negron served in the fabled 65th Inf. Regt., which was attached to the 3rd Inf. Div. during the Korean War. The Borinqueneers were among the first Soldiers to confront the enemy on the peninsula. They also launched the last-recorded battalion-sized bayonet charge and overran the Chinese 149th Division in February 1951. Negron lived up to this reputation, Apr. 28, 1951, while serving in Company L. He took up the most vulnerable position on the company's exposed right flank after the enemy overran a section of the line. He refused to leave his post, even after his company began to withdraw. He held his position throughout the night. By the next morning, the bodies of 15 enemy soldiers surrounded him. Negron retired from the Army as a master sergeant. He was posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor in 2014.

Drafted into the Army in October 1950, then-Pfc. Joseph C. Rodriguez found himself in Korea with Company F, 2nd Battalion, 17th Infantry Regiment, 7th Inf. Div. less than a year later. May 21, 1951, Rodriguez led his squad on a mission to take a hill near the small village of Munye-Ri. The squad was soon pinned down by a barrage of automatic and small-arms fire on three sides. "I felt something had to be done," Rodriguez said during an oral history interview. "I didn't even think about it. I just did it." He leaped to his feet and sprinted 60 yards toward the top of the hill. As bullets sprayed the ground around him, Rodriguez destroyed five foxholes with grenades, killing a total of 15 enemy soldiers. He received the Medal of Honor the following year. Rodriguez became a commissioned officer with the Corps of Engineers and eventually retired as a colonel.

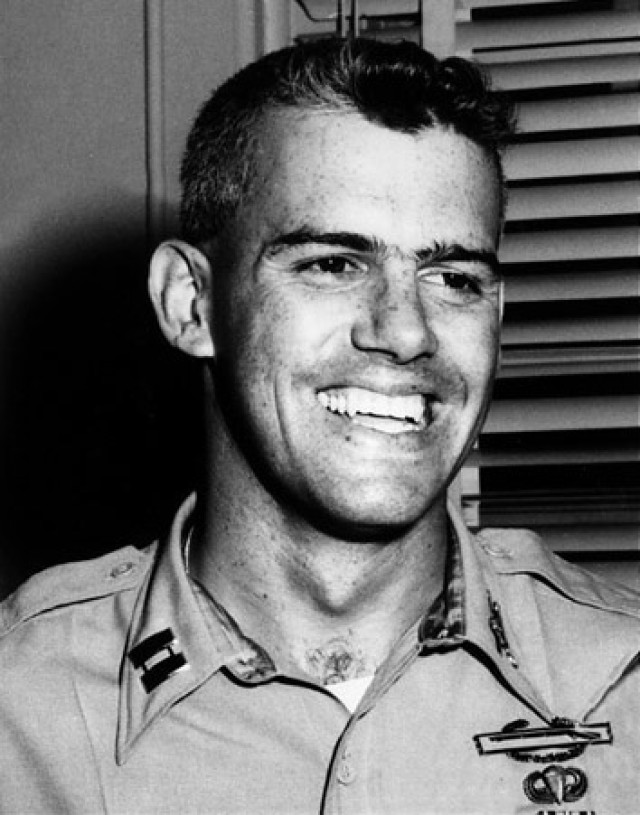

Corporal Rodolfo "Rudy" Hernandez and Company G, 2nd Battalion, 187th Airborne Regimental Combat Team dug in at Hill 420, about 15 miles south of the current Demilitarized Zone near Wontong-ri, South Korea, May 31, 1951. They heard the North Korean bugles that heralded a charge at about 2 a.m. A much larger force attacked their position with heavy artillery, mortar and machine gun fire. They quickly ran low on ammunition and began to withdraw. Not Hernandez. Although he had been wounded by a grenade, he wanted to buy his comrades time. He fixed his bayonet and rushed the enemy. He killed six enemy fighters before losing consciousness from his injuries. His actions momentarily halted the enemy advance, giving his unit a chance to retake the lost ground. A medic found Hernandez at daybreak, wounded so severely that he was declared dead at the aid station. Medics were actually preparing to zip him in a body bag when one of them saw his finger move. After months of rehab, Hernandez was able to stand for his Medal of Honor ceremony in April 1952. He eventually joined the Department of Veterans Affairs, working with other wounded veterans in North Carolina.

Cpl. Benito Martinez, Cpl. Joe R. Baldonado, Sgt. Victor H. Espinoza, Sgt. 1st Class Eduardo C. Gomez, Master Sgt. Mike C. Pena, Pvt. Miguel A. Vera and Pvt. Demensio Rivera also received Medals of Honor for valor above and beyond the call of duty during the Korean War.

VIETNAM WAR

Born to an Army colonel and a Puerto Rican author, Capt. Humbert "Rocky" Versace received his commission at the U.S. Military Academy at West Point, New York, in 1959. After graduating from Ranger and Airborne schools, he served in Korea with the 1st Cavalry Division. He then volunteered to go to Vietnam as an advisor. In October 1963, Versace's South Vietnamese unit came under intense mortar, automatic weapons and small arms fire during a mission to destroy a Viet Cong command post. Although he was severely wounded in the knee and back, Versace continued to fight and resist capture as long as he had ammunition. After he was finally taken prisoner, Versace, who could speak French and Vietnamese, withstood exhaustive interrogations, torture and abuse for 23 months without breaking. He attempted to escape four times and inspired other prisoners of war. In fact, the last time they heard his voice, he was singing "God Bless America." Versace was finally isolated from other POWs in a series of jungle camps, caged, manacled and placed on extremely reduced rations. The North Vietnamese announced his execution, Sept. 26, 1965. His body has never been recovered. Versace was nominated for the Medal of Honor in 1969 when an escaped POW documented his bravery, but the award was downgraded to a Silver Star. He was finally awarded the medal in 2002.

While serving near Loc Ninh, Vietnam, May 2, 1968, with Detachment B-56, 5th Special Forces Group, then-Staff Sgt. Roy P. Benavidez received a distress call from another Special Forces team. He later said he heard "so much shooting (on the radio), it sounded like a popcorn machine." Upon reaching the scene, Benavidez, who had already been seriously wounded on a previous tour, leaped off the helicopter and ran through 75 meters of unrelenting fire, getting shot in his right leg, face and head. He carried wounded men aboard the helicopter, then attempted to recover a fallen Soldier and classified documents, sustaining more severe wounds in the process. After the helicopter pilot was killed, Benavidez organized a perimeter, returned fire, called in air strikes and distributed ammunition, medicine and water. When another aircraft was finally able to land, Benavidez ferried his comrades to the helicopter through devastating fire. By the time he reached safety, Benavidez was unable to move or speak and was riddled with more than 30 wounds. Just as he was about to be placed into a body bag, he spit into a doctor's face. He remained in the Army, retiring as a master sergeant in 1976. Benavidez's Distinguished Service Cross was upgraded to the Medal of Honor in 1981 after investigators located a witness to his actions.

Sergeant Santiago J. Erevia enlisted in 1968. He deployed to Vietnam with Company C, 1st Battalion (Airmobile), the 501st Infantry Regiment, 101st Airborne Division. May 21, 1969, Erevia's battalion assaulted a hill near Tam Ky. While he was guarding the wounded, his position came under attack from four enemy bunkers. Crawling through a hail of bullets, Erevia collected weapons and grenades from the wounded Soldiers and crept forward with a buddy, who was quickly killed. "I said, 'Well, I have no choice. They can die. So can I,'" he remembered. Under intense fire, Erevia kept moving forward and threw grenades into three foxholes. Then, running and firing two M16s simultaneously, he fought his way to the last bunker and singlehandedly destroyed that one as well. After the war, Erevia battled post-traumatic stress disorder and went to work for the U.S. Postal Service. Initially awarded the Distinguished Service Cross, Erevia received the Medal of Honor with 23 other veterans in 2014.

(Spc. 4 Daniel Fernandez, Capt. Euripides Rubio, Staff Sgt. Elmelindo R. Smith, 1st Sgt. Maximo Yabes, Pfc. Carlos James Lozada, Spc. 4 Hector Santiago-Colon, Sgt. 1st Class Louis R. Rocco, Spc. 4 Alfred V. Rascon, Spc. 4 Leonard Alvarado, Sgt. Jesus S. Duran, Staff Sgt. Felix M. Conde-Falcon, Sgt. Candelario Garcia and Sgt. 1st Class Jose Rodela also received Medals of Honor for valor above and beyond the call of duty during the Vietnam War.)

OPERATION ENDURING FREEDOM

While assigned to Company D, 2nd Battalion, 75th Ranger Regiment, then-Staff Sgt. Leroy Petry participated in a rare, daring daylight raid to capture a high-value target in Paktya Province, Afghanistan, May 26, 2008. He was clearing a courtyard with another Ranger when an enemy combatant opened fire, wounding Petry in the legs and hitting his comrade in his side plate. Petry helped his Soldier take cover in a chicken coop and threw a grenade toward the enemy to cover the arrival of a third Soldier. An enemy grenade injured both of the other Soldiers, and then a second landed a few feet from them. As Petry grabbed the grenade -- he called it "instinct" -- and threw it away from his fellow Rangers, it detonated and amputated Petry's right hand. Petry then assessed his own wound and placed a tourniquet on his right arm. At that point, other Rangers, one of whom was killed, were able to target and destroy the enemy. Petry became the second living Medal of Honor recipient from the war in Afghanistan in July 2011. He retired from the Army as a master sergeant in 2014.

Editor's Note: Soldiers has identified most of these heroes as Hispanic based on their recognition by the Hispanic Medal of Honor Society, and has heavily relied on citations available from the U.S. Army Center of Military History. (Soldiers are identified by the ranks listed on their citations.)

Related Links:

Army.mil: Hispanics in the U.S. Army

Center of Military History: Hispanic Americans in the U.S. Army

Social Sharing