Part Four: Grant's Canal

During the summer of 1862, as the Union fleet maintained an intermittent and ineffective bombardment of the Confederate batteries at Vicksburg. Union Flag Officer David Glasgow Farragut realized that he could not compel the surrender of the fortress city based solely on the might of his naval guns. Fortunately, a brigade of soldiers commanded by Brig. Gen. Thomas Williams had accompanied the squadron upriver from the Gulf. Farragut turned to Williams and asked if he thought his 3,200-man force strong enough to take the city. The plan advanced by Farragut was for the infantrymen to be placed on transports and, under the protective fire of the fleet, rush across the river and storm the bluffs.

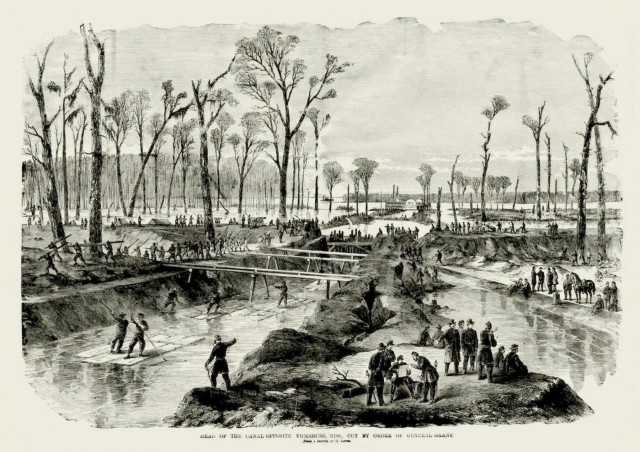

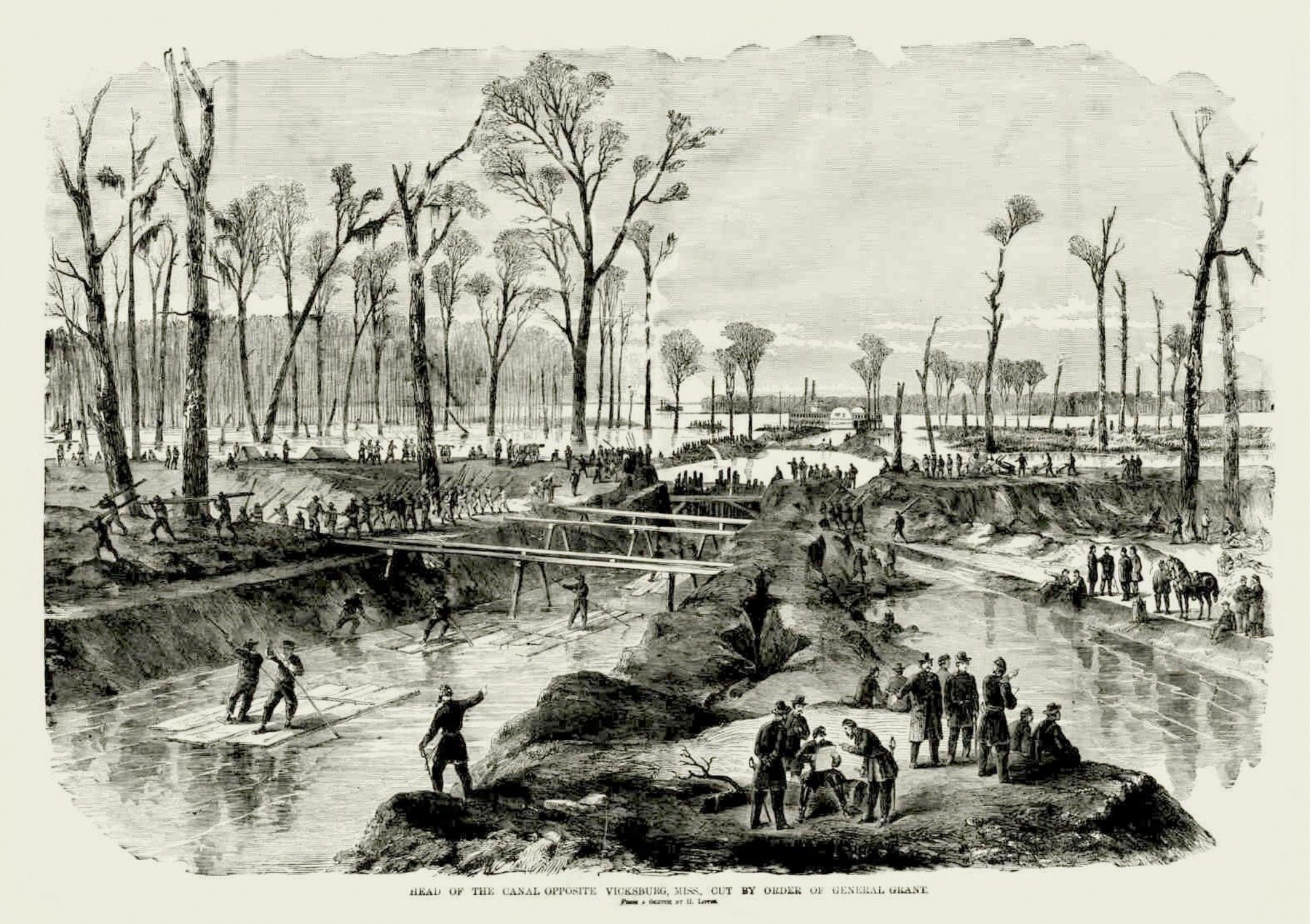

In light of the perceived strength of the Confederate shore batteries, Williams was shocked by the mere suggestion and offered an alternate course of action. The general was a native New Yorker who had graduated from West Point in 1837 and received two brevets for gallant and meritorious service during the Mexican War. He recommended that his men be placed ashore in Louisiana to excavate a canal across the base of De Soto Point, opposite Vicksburg. If successful, the canal would open a channel of navigation that would bypass the Confederate batteries and render Vicksburg militarily useless.

The proposed canal was to be one and a quarter miles in length with a depth of thirteen feet and adequate width to accommodate the oceangoing vessels of Farragut's squadron. Work commenced on June 27 and Williams' soldiers labored with ax and saw, pick and shovel to clear the forest and excavate the canal. The general, however, soon discovered that "The labor of making this cut is far greater than estimated by anyone."

Compounding the problems presented by nature, the soldiers hailed mostly from New England and the upper Mid-West. These men were not accustomed to the temperature and humidity extremes of the Deep South and quickly fell victim to heat exhaustion, sunstroke, malaria, and various other maladies that rapidly reduced the effective strength of his command. In short order Williams' work force dwindled to fewer than 800 men.

In order to keep work on the canal going, Williams pressed into service 1,200 slaves from plantations in Madison and Tensas Parishes and put them to work on the canal. Most of the able-bodied field hands, however, had been evacuated by their owners prior to the arrival of the Federals. Left behind were the aged and infirm, women, children, and slaves that worked mainly as house servants. Yet, these people were put to work laboring on the canal. Not accustomed to working in such harsh conditions they, too, fell victim to the same maladies that plagued the soldiers.

Despite widespread sickness among the soldiers and slaves who toiled on the canal, by mid-July the motley workforce had reached the desired depth of thirteen feet and the channel had an average width of eighteen feet. But the Mississippi River was falling fast and the surface of the water dropped well below that of the canal, which compelled them to dig even farther down. As they did so, the walls of the ditch caved in several locations and Williams was forced to concede failure.

By this time the rapidly falling river also threatened to strand Farragut's fleet far upriver from the blue water to which it was accustomed. On July 24, Farragut's ships and what was left of Williams' command gave up and headed south to Baton Rouge.

Social Sharing