FORT BENNING, Ga., (Nov.4 2015) -- The National Infantry Museum houses the history of the Infantryman, from the American Revolution to the contemporary wars in the Middle East. On display are nearly 3,500 artifacts, all of which tell the story of the nation and its Soldiers.

Jeff Reed, Arms curator, and Justin Batt, archivist, consider themselves guardians of the museum's collections. They are among only a few who have access to the more than 25,000 objects the museum does not have on public display.

Reed said there are several reasons why the museum stores more artifacts than it displays. Many of the items are on rotation.

"We try to adhere to that schedule the best we can, especially with sensitive items like textiles," he said. "You want to rotate them and give them an opportunity to rest. We store them downstairs in a strictly controlled environment."

One exhibit that has items on rotation is the Col. Ray O'Day display. O'Day's collection includes materials that he made as a prisoner of war in Japan during World War II. Because he was an officer, he knew he had a responsibility to inspire his men, who were also enduring the harsh life of a POW.

"Col. O'Day was very resourceful. When you look at his collection, it's a combination of hobbled together tools and clothing he created out of scraps. You open up his collection drawers and there are bent nails and screws and pipefittings, but these are all things he had value in and that he could use to create comfort items," Reed said.

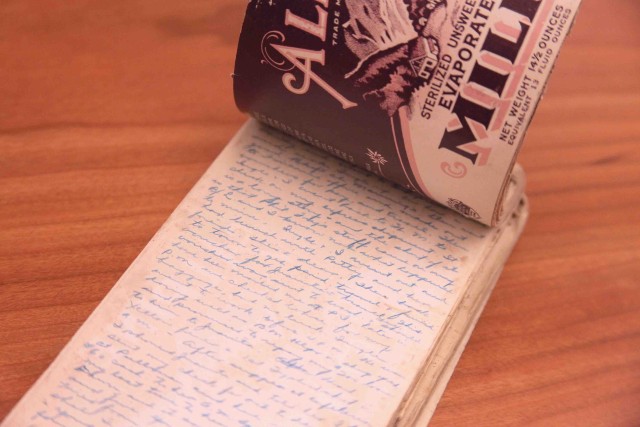

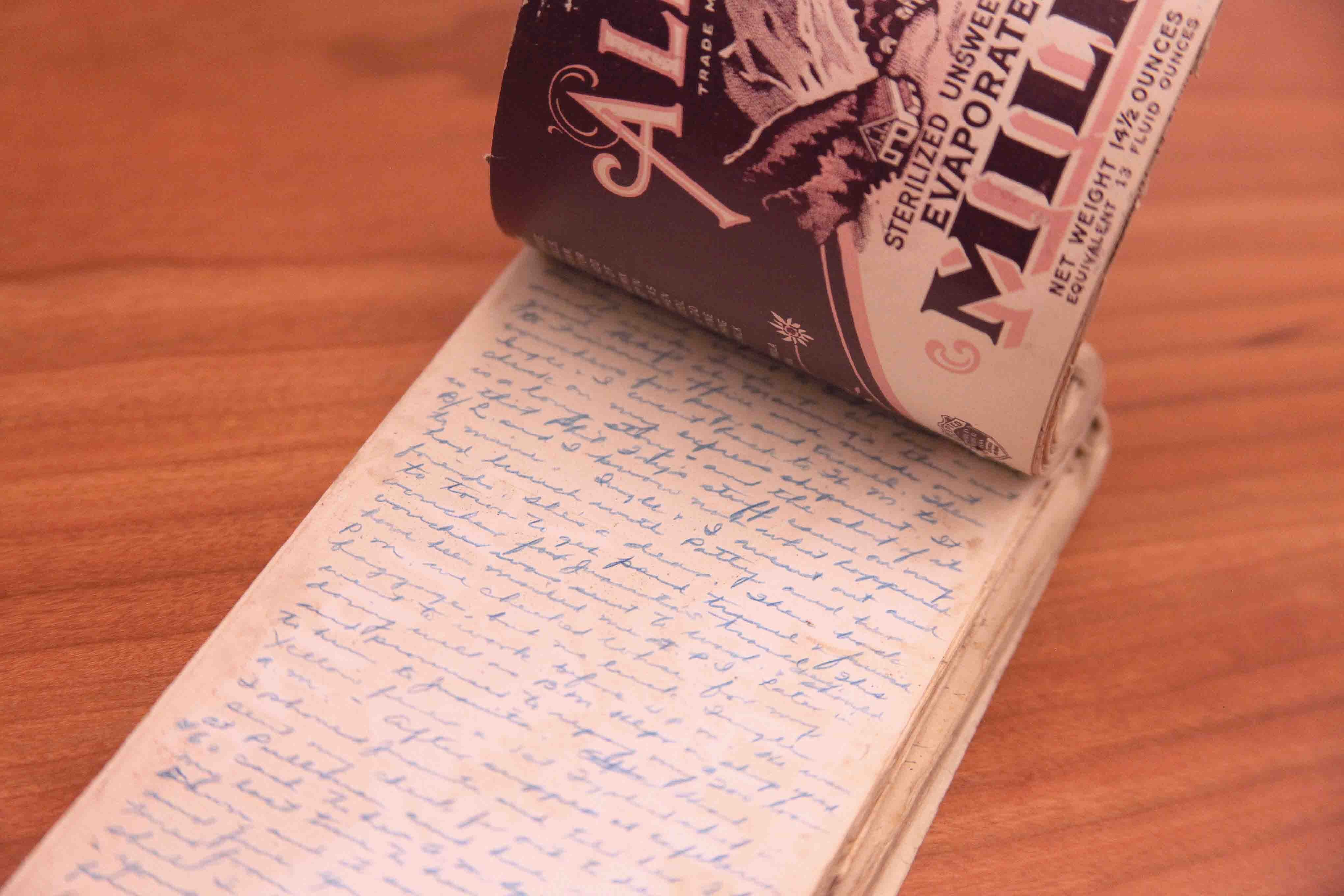

One item from O'Day's collection that is not on display is his POW journal.

"The thing about the diary was they were not authorized to keep diaries, in fact they were forbidden to do that," Reed said. "For his initial source of paper, he uses official forms he finds in the dump. When that supply runs out, he resorts to taking the labels off milk cans and he writes on the back (of those labels.)"

Reed said O'Day's journal brings life to his collection.

"The great thing about the diary is it tells us what a lot of those objects are and what he used them for and how he created them," Reed said. "When you can cite the exact words, 'I took a piece of sheet iron and hammered it into a bowl so we could have a bread bowl ... I got some rice bags and made shorts out of them' ... It's an incredible document."

Some items are not displayed because, although they are important objects in history, they are either mundane or their stories cannot be easily told.

Reed showed an empty parachute reserve tray as an example of a mundane, but important object.

The parachute was found in an old farm building in Sainte-Mere-Eglise, France, seven kilometers from the shores of Normandy.

Reed said they assume that a Soldier jumped in during the invasion of D-Day and the parachute reserve was later found by a French woman.

"More than likely the reserve wasn't used, but most of the reserves at that time were either white nylon or silk and that was very sought after by the local French, because they had basically been occupied by the Germans. It was not uncommon to see French girls running out after these parachutes," Reed said.

Reed showed a handmade violin from the Vietnam War as an example of an artifact whose story cannot be told.

"Unfortunately we don't know a lot about it," Reed said. "The donor was anonymous and all we know is it was made in Vietnam out of ammunition crates. "We know there is a story there, but without the story we are just left wondering. It would have been incredible to know the veteran who made it and get his story and his circumstances and the conditions that he made it under."

Many of the pieces in the museum's possession are used only for research.

Batt said besides having an extensive three-dimensional collection, the museum also has a lot of archival documents and photographs.

He is currently working with a researcher who is writing a book about photographs from the U.S. Army Signal Corps.

"He has been able to identify, through a series of numbers that are on the images, who the photographer is and where the images were taken," Batt said.

Batt is also working on a future archival project for the museum that will feature the scrapbook of Col. Harry "Paddy" Flint, for whom Fort Benning's Flint Range is named.

Flint had a long and inspiring military career. He was commissioned at West Point in 1912 and was killed in action 32 years later on the opening day of Operation Cobra in WWII.

Among the items in his scrapbook are photographs of Flint and Gen. George Patton, as well as a letter sent from Patton, during his time at Fort Benning, the day before Pearl Harbor requesting that Flint be sent to serve with him.

"What ends up happening when he gets to North Africa is they fought through Italy and the 39th Infantry Unit is performing below par. So Flint is chosen as the colonel to lead them and he tries to think of different ways to inspire them,"Batt said.

During his effort to inspire his men, Flint created the motto AAAO - Anything, Anytime, Anywhere or Nothing.

"He creates not only their own patch (with that acronym), but he also has his men write it on their helmets," Batt said. "The men love it. They walk around with pride. He turned the unit around and they became a very well-oiled fighting machine."

Batt said he hopes to have pieces from Flint's scrapbook on display by next summer.

Social Sharing