WASHINGTON (Army News Service, Aug. 5, 2015) -- Army researchers have found effective techniques to dramatically improve Soldiers' cognitive and physical abilities through a regimen of mental skills training.

Success of the study led the Army to permanently incorporate cognitive skills training into basic combat training. And, following the research done at Fort Jackson, South Carolina, that training has since spread Army-wide, delivered by trainers from Comprehensive Soldier and Family Fitness, or CSF2.

Much of the study's design was derived from previous research conducted at the Center for Enhanced Performance at the U.S. Military Academy, West Point, New York. That center now serves as the core element of CSF2 under the Army Resiliency Directorate, according to Amy B. Adler, a clinical research psychologist at the Center for Military Psychiatry and Neuroscience, Walter Reed Army Institute of Research, Silver Spring, Maryland.

Adler and others conducted the study and published their findings in the article "Mental Skills Training with Basic Combat Training Soldiers: A Group-Randomized Trial," published May 25, 2015, in the Journal of Applied Psychology.

The Army funded the research, hoping to improve recruits' basic combat training performance using mental skills training techniques, Adler said, adding that most of her colleagues in the study had a background in sport psychology as well as research.

"No one has ever done this kind of study using sport psychology techniques before. A lot of these types of studies have been correlational in nature," she said, meaning there wasn't a cause-effect relationship established, and, a lot of the measures of effectiveness outside the research environment were anecdotal in nature.

Also, past studies tended to be small, using elite athletes, she said. That would have the effect of reducing the reliability of the study and it would also make it harder to generalize the findings to recruits, who are most likely not elite athletes.

By big study, Adler pointed out that 2,432 recruits were randomized by group across 48 platoons. Each group, in this case a platoon, would either be the mental skills training group or the active comparison group. Size and randomization would increase the validity of the experiment and confidence in any significant findings.

Rather than using just a control group, using an active comparison group gave the experiment more validity because it mimicked the mental skills training group in every way except for the content delivered. The active group received a lecture on military history, which was considered to be useful to the recruits, Adler noted. Both groups received a total of eight hours of training spread out across 10 weeks.

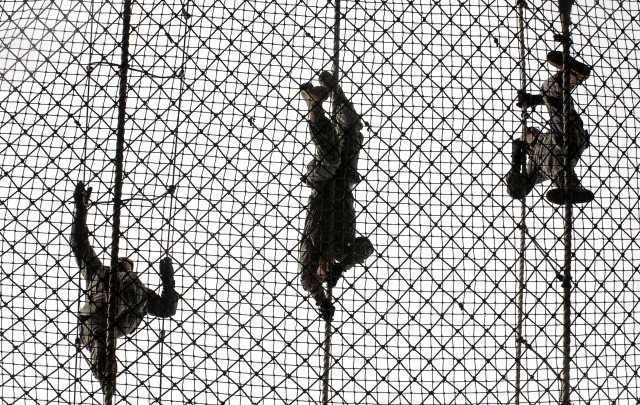

The mental skills training was conducted in bite-sized chunks of about 20 minutes each, distributed throughout various field training events such as the obstacle course; rappelling; rifle range; chemical, biological, explosive, radiological and nuclear, or CBERN training; Army physical fitness test and so on, rather than in just one block of classroom instruction, she said.

Each training chunk was relevant to the event, she added. For example, prior to CBERN or rappelling, relevant material related to managing anxiety would be given. The active group during this time would get a history lesson on rappelling, beginning in World War I.

The raters looked at things like time to completion as well as post-training attitudinal attribute ratings like "the training helped me," "the training helped bring the platoon closer together," "the training will help me in the future," and so on, Adler explained.

COGNITIVE SKILLS TECHNIQUES

Coreen Harada, a sport psychology consultant and member of the research team, said that six mental skills were used in the study: mental skills foundations, goal setting, energy management, attention control, integrating imagery and building confidence.

Those techniques were aimed at developing the right attitude; cognitive control over physiological functions such as muscles, breathing rate, anxiety levels and so on; focusing attention on the task at hand; organizing efforts into goals; and, utilizing visualization or imagery for task execution, she said.

For example, in rifle marksmanship, goal setting, energy management and attention control, three of the six skills, were used, she said. In energy management, recruits focused on controlling heart rate and breathing. Since the rifle range was a novel task for many, that experience would tend to elevate stress levels.

Recruits were trained to control their thoughts and their breathing through practice sessions prior to going to the range. Harada said recruits were told that nervousness before an event like marksmanship and rappelling is normal and could even be used to their advantage.

For instance, rapid heart rate means the heart is pumping vital nutrients to the brain and the body so that's a good thing, she said. By focusing on breathing control and visualizing and mentally rehearsing technique before the event, performance would improve.

The first of the six skills, which is mental skills foundations, would always be the first taught, Harada said, because it is critical to all of the other skills. The foundation training consists of having the right mindset for success, focusing on one's ability to grow, optimism, effective thinking and seeing failure as a normal occurrence on the road to success.

Confidence building tasks consisted of positive self-talk, she said, rather than engaging in a lot of self-criticism that brings you down, distracts and de-energizes.

OTHER RESEARCH ASPECTS

The entire experiment was overseen by an institutional review board, which monitors the design for ethical and safety issues, as well as acquiring participants' consent, Adler said.

Both groups, active and mental, had some of their training performance videotaped. Raters unaware of the details of the study were then asked to watch the videos and rate the performance of all the Soldiers going through their events. This added a great deal of validity to the study, she said.

Gender and previous experience were moderators of outcomes, Adler noted. Not everyone benefited equally for each task, but there was also no deterioration of performance across the mental study group irrespective of gender, and, taken as a whole, everyone benefited.

Adler added that besides the study benefiting performance, the study also had a positive side effect of building mental skills and recruits may have worked as platoons to encourage each other in rehearsing the various mental skills techniques prior to the events. This group effect most likely reinforced performance as well.

ARMY-WIDE IMPLEMENTATION

The study's success led to implementation of a condensed version of mental skills training to every recruit. Two-and-one-half hours of mental skills training is provided per platoon by drill sergeants, each of whom have been trained in the techniques, according to Harada.

Harada said Soldiers, families and Army civilians Army-wide are also now getting mental skills training though CSF2, delivered in a variety of ways such as in a classroom setting, during field exercises, and at the school houses.

Master resilience trainers also provide some of the training in their own venues, she added.

Mental skills training is continually reviewed and revised by CSF2 as new research and findings emerge, Harada said. And, new findings reviewed are not just from sport and exercise psychology. For instance, the literature from adult learning is examined. Also, similar applications of mental skills training are studied from the business community as well as first responders.

In turn, Harada said she believes that the Army study has influenced a number of civilian practices. For example, the lead trainer in the study, Bernie Holliday, who is one of the authors of the study, now works for the Pittsburgh Pirates, providing the baseball players with mental skills training he helped to develop.

Besides Adler, Holliday and Harada, other authors of the study were Paul D. Bliese, who had been the director of the Center for Military Psychiatry and Neuroscience at the Walter Reed Army Institute of Research and is now a retired Army colonel and professor at the University of South Carolina; Jason Williams, a statistician from Research Triangle Institute, Research Triangle, North Carolina; Louis Csoka; Michael A. Pickering and Jon Hammermeister, now both faculty at Eastern Washington University; and Carl Ohlson, now a retired Army lieutenant colonel who had directed the Center for Enhanced Performance at the U.S. Military Academy.

Adler noted that Csoka, a retired Army colonel, set up the program from the beginning and helped design the experiment when he was a contractor with Apex Performance, Inc., Charlotte, North Carolina, so it would meet "gold standard" criteria for publication in one of the most prominent psychology journals.

The Center for Military Psychiatry and Neuroscience at Walter Reed Army Institute of Research partnered with CSF2 in setting up the study, Adler mentioned.

The Center for Military Psychiatry and Neuroscience's Research Transition Office took the completed study and transitioned it to implementation for basic combat training, she said.

Social Sharing