This year not only marks the 90th anniversary of the armistice that silenced the guns of World War I, it is also the 30th anniversary of the dissolution of the Women's Army Corps and integration of women into the regular Army.

America entered the war in April 1917 with a saturation campaign aimed at overwhelming the enemy to bring the war to a rapid end. To accomplish this goal, the U.S. needed to raise a multi-million strong fighting force and Congress passed the Selective Service Act May 18, 1917, which required males aged 21 through 30 to register for military service.

When the U.S. entered the war, the armed services numbered 110,000 service members. By the time the war ended, 24 million men had registered and 2.8 million had been drafted.

Conscription of men changed the role of women in war forever. The changes in gender roles brought on by the war permitted women to step out of their prescribed roles for the first time.

Shedding ribbons and satin and donning coveralls and serge uniforms, many women left their homes and took up positions in factories manufacturing munitions, gas masks and other war production.

In her book, "Rosie's Mom: Forgotten Women Workers of the First World War," Carrie Brown writes that more than 1 million American women shed conventional roles and joined in the war effort.

Others ran to military recruiting stations in search of positions in uniform. According to the Women's Overseas Service League, approximately 90,000 women served in uniform in World War I.

The Navy and Marine Corps enlisted women as clerks, radio electricians, chemists, accountants and nurses. Others joined the Young Women's and Young Men's Christian Associations, the American Red Cross and the Salvation Army.

The Army, unlike its sister services, was more conservative in the jobs it permitted women to fill its ranks, enlisting more than 21,000 as clerks, fingerprint experts, journalists and translators.

Prior to the nation's involvement in the war, the Army Nurse Corps numbered 403 active-duty nurses; by war's end in 1918, the corps consisted of more than 12,180 nurses serving in 198 stations and base hospitals worldwide as nurses and occupational therapists.

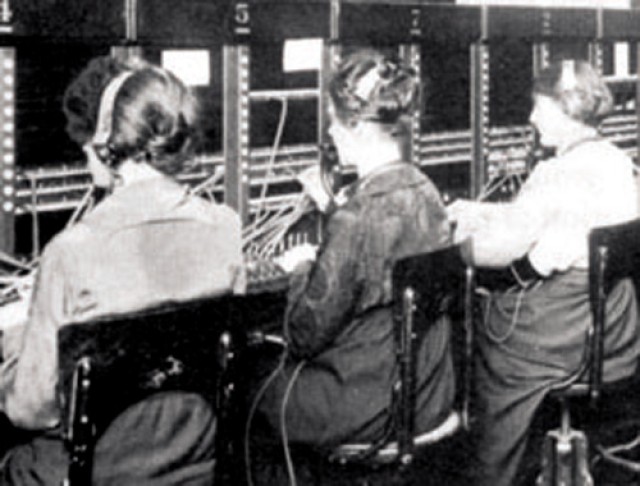

The Army Signal Corps also utilized women, enlisting 700 women, 332 of whom served overseas as bilingual French-speaking telephone operators. Although the Army nurses and operators were subject to the Uniform Code of Military Justice and Army regulations and wore uniforms, they had no rank.

The Army regarded them as "civilians" employed by the War Department. It was not until the second World War that women were assigned the ranks of lieutenant or captain, and then it was only "relative rank," meaning that even though the women held all of the responsibility and respect afforded to the positions, they received far less pay and none of the benefits received by their male counterparts.

At war's end, the women were released without any official recognition. Women's service in both world wars was not recognized until the passage of the Army-Navy Nurses Act of 1947.

The act conferred women currently serving in the ANC with ranks of commissioned officers ranging from second lieutenant through lieutenant colonel. Women who served in the previous wars were also presented with honorable discharges from military service.

World War I allowed women to shed their roles of domesticity for the first time and permitted them the chance to work alongside men toward the national goal of victory.

After the armistice, the great adventure ended and women returned home, many finding it difficult to readjust. In a letter to her family, one unnamed nurse described her experience while serving with Soldiers on the front, "You are in another world, and ... given new senses and a new soul."

Shari Wigle is a historian and author of "Pride of America We're With You," which includes the letters of Grace Anderson, a World War I Army nurse and the grandmother of Wigle's nephew, Dana Lynn.

In a recent interview, Wigle stated, "The nurses did suffer- they had great difficulties adjusting to their lives here because after working 14 and 18 hours a day, and all the horrors and coming back, working as nurses here was quite a change," she said.

Wigle went on to describe how women coped with adjusting to "normalcy" after the horrors they had witnessed overseas.

"They [the nurses] had a sisterhood - they kept in touch and wrote to each other, because no one else understood what they were going through. They were just expected to come back and go on with their lives," she said.

Women's contributions did more than help America defeat her enemies. Their participation also made a powerful argument for women's voting rights, weighing heavily in the passing of the 19th Amendment giving American women the right to vote.

President Woodrow Wilson appealed to the U.S. Senate in September 1918, asking members to consider the contributions and successes of women during the war before repudiating the bill that would give women the right to vote.

"We have made partners of the women in this war; shall we admit them only to a partnership of suffering and sacrifice and toil and not to a partnership of privilege and right'" Wilson asked.

Wilson's appeal, the pressure of the suffragists, and the contributions and sacrifices of women in the defense of the nation swayed the vote and contributed to the expanding roles of women in society and defense today and beyond.

Social Sharing