Editor's note: Following is the first in a two-part series about a 10th Mountain Division (LI) Soldier who established a foundation in memory of his son.

FORT DRUM, N.Y. -- Infantryman Sgt. 1st Class Joshua Swink has always been the type of person who works through the challenges that life sends his way. An avid athlete, Swink has competed in seven marathons, nine ultra-marathons and an assortment of other extreme physical fitness challenges across the United States.

Each of these events challenged him mentally and physically, he said, yet none tested his ability to endure as much as the events of the last year, as Swink has navigated the difficult course of learning to carry on after the loss of his oldest son.

Swink was attending a small community college in rural North Carolina in 2002, when he decided to enlist in the Army.

"My brother was in the National Guard, and he kept trying to convince me to join," Swink said. "I went and talked to a recruiter and was offered an airborne package. It sounded like a challenge that would be a lot of fun."

He completed basic training and when straight into Airborne School, both at Fort Benning, Ga. During his second week of Airborne School, Swink received a message that he had been anxiously anticipating.

"My wife and I were expecting our first baby, and she was two weeks late," he said. "I had gone home right after basic, thinking that the baby would be born then, but he was stubborn."

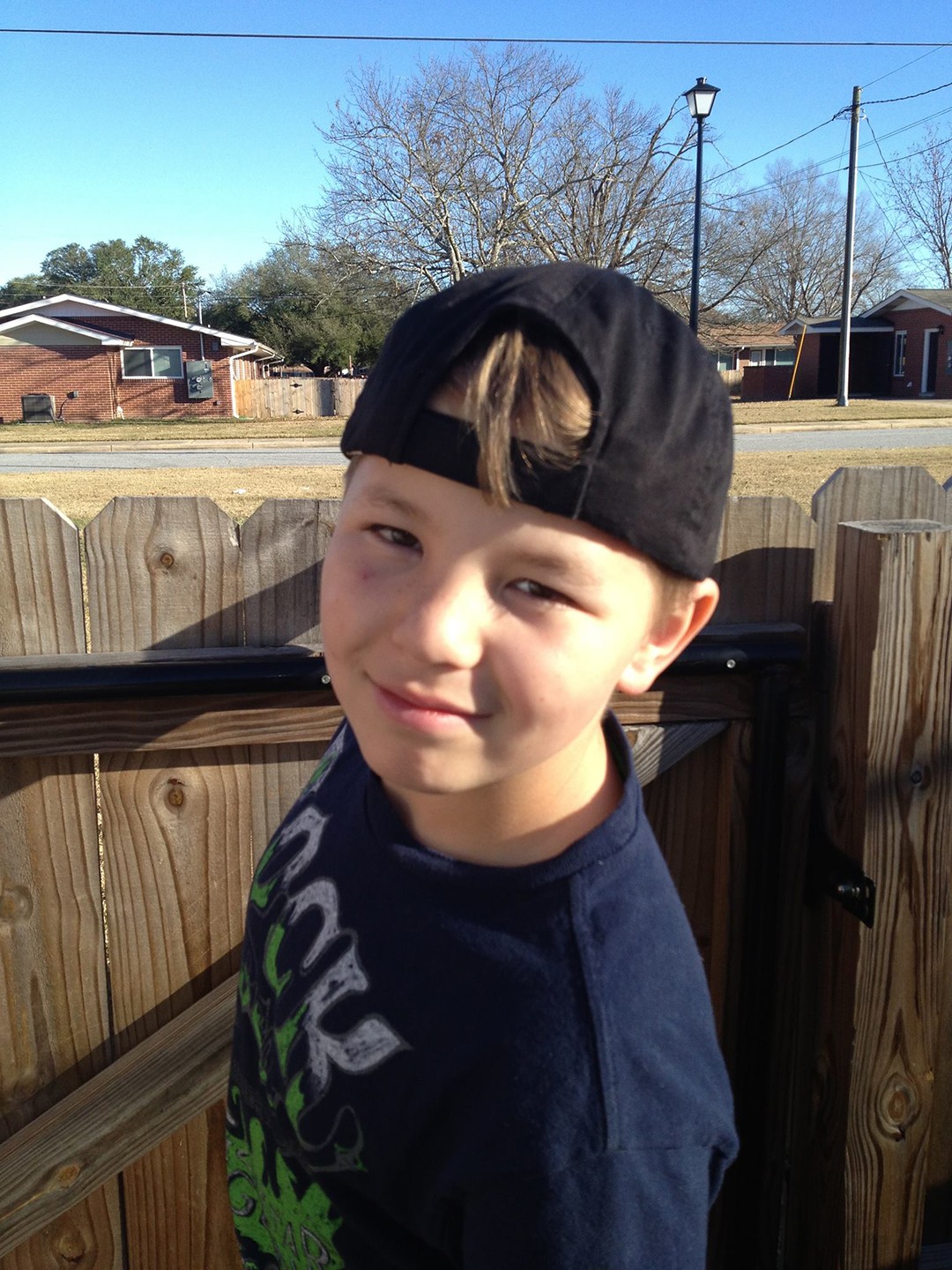

After completing a day of rigorous training on Friday, May 9, 2003, Swink was informed that his son, Beydn, had been born at 12:41 p.m.

"I drove straight from Fort Benning to North Carolina," he said. "When I first got there, he was in the nursery with a minor infection. I couldn't hold him right away because he was sick. When I finally did get to hold him, I remember thinking 'he's so small.'"

Swink spent the weekend with his wife and newborn son, leaving early Monday morning to resume his airborne training.

"The whole next week at Airborne School, all I could think about was getting things done so I could get back home to Beydn," he recalled.

Just 10 days after completing the course, Swink was heading to Iraq with the 101st Airborne Division, based at Fort Campbell, Ky.

"That's pretty much the way my whole Army career has gone -- everything has been busy, one thing right after another," he said. "I like the intensity of the infantry; I like change, and I like to keep moving."

Swink said his first combat tour was relatively smooth.

"We spent most of our time in northern Iraq," he said. "Basically, we went in and took control of towns. The resistance level of the initial invasion was lower (than consecutive deployments), at least for the unit I was in."

Although his combat tour was uneventful this time, Swink's marriage had begun to fall apart. He and his wife separated during this first deployment and divorced in 2004. The two maintained an amicable relationship and shared custody of Beydn.

When Swink's ex-wife remarried, she and her husband were stationed at Fort Campbell, the same post where Swink was stationed at the time. This allowed Swink to visit with Beydn regularly, and both Families loved the arrangement.

"Beydn lived with them on the Tennessee side of Fort Campbell, and I lived just on the Kentucky side," he said. "It was really great. He could call up anytime he wanted to come and stay with me for a few days and I would pick him up. We had it worked out well."

When Beydn's mother and her spouse were stationed at Fort Riley, Kan., Swink made the 14-hour drive to see his son as often as possible. Beydn also came to visit, staying with his father at Fort Campbell and later at Fort Jackson, S.C., where Swink spent two years as a drill sergeant.

Swink remarried in 2008, and his second son was born in 2009. Between Beydn's father and mother, the boy had six siblings -- four boys and two girls.

"We always used to say that he was the ultimate brother," Swink said. "He was always looking out for the other kids."

In May 2012, Swink was stationed at Fort Drum, and he immediately applied for the Division Pathfinder Company, part of 10th Combat Aviation Brigade's 2nd Battalion, 10th Aviation Regiment. He made it through the selection process, and he was thrilled to have the opportunity to complete his training at Fort Benning, Ga., where Beydn then lived with his mother and Family.

It was while away on deployment with the Pathfinders in November 2013 that Swink received a message that would change his life.

"I came off a guard shift and got on Facebook at 4 a.m., and I had a message from my ex-wife that said 'you need to call me,'" he said.

The two were able to speak using Facetime, and she told him that Beydn had been diagnosed with leukemia.

"His mom explained that he hadn't been feeling well," Swink recalled. "He was athletic -- he liked to run and ride his bike, and he was very energetic. So, when she said he wasn't hungry and didn't want to get out of bed, she took him to the hospital at Fort Benning."

The hospital laboratory ran tests, and Beydn's white blood cell count came back extremely high -- an indicator that something was very wrong.

He was taken by ambulance to The Children's Hospital of Atlanta at Scottish Rite, where he was diagnosed with acute T-cell lymphoblastic leukemia, a type of blood cancer.

"The Army got me home fast. I found out Beydn was sick Nov. 3, and I was in Atlanta with him Nov. 6," Swink said.

Knowing that Beydn's treatment would be intensive, and wanting to be close to his son, Swink began researching his options and soon stumbled upon the rules for a temporary compassionate leave attachment.

"I was sitting in the hospital room while Beydn was sleeping, and I read the entire manual on leave, passes and exemptions online," he said. "I called the rear detachment first sergeant and Human Resources Command, and they made it happen."

Swink was attached to a local recruiting station in the Atlanta area for an initial period of 120 days.

The course of treatment that Beydn underwent was intensive.

"He was sedated in the Pediatric Intensive Care Unit for about five days; then he was moved downstairs to the Blood Disorders Unit," Swink said. "Once he was moved downstairs, he was awake and he was put on steroids to keep his energy up."

A fifth grader at the time, Beydn continued to do homework during the day, and he loved to read when he wasn't too tired. His parents took turns sitting by his side 24 hours a day.

"I would stay with him all night, and his mom would stay all day," Swink said. "Sometimes at night I'd sit and watch the monitors and see his heart rate dip down into the 40s, and I knew he was really resting comfortably."

After eight days in the hospital, Beydn was sent home to rest for a few days before beginning his next round of chemotherapy.

"When he got back, his electrolytes and sodium levels were crazy, so they kept him for another week," Swink recalled.

Beydn was able to go home one more time, but when his stomach became distended on Dec. 6, he had to return to the hospital. The next day, he was readmitted to the Pediatric Intensive Care Unit.

"He started getting better, and then a fungal infection showed up," Swink said. "He had no immunity because the chemotherapy had wiped him out, and he caught everything."

Although Beydn's blood tests on Dec. 11 showed he was in remission from his leukemia, an invasive fungal species, Scedo-

sporium, had begun to spread through his organs and blood. There is no medication to treat this specific kind of fungal infection, so Beydn was sedated and his doctors spent three weeks administering a variety of antifungal medications, hoping one would work.

"The day we made the decision to stop the antifungals, he was supposed to have a CT scan," Swink recalled. "They explained that if they took him off all the supports to take him down for the CT scan, he might die during the scan."

Beydn's infection was not responding to any of the antifungal medications, and he now weighed less than 60 pounds. His liver wasn't functioning properly, and he was on kidney dialysis.

His parents made the difficult decision to remove him from life support. In the days that followed, Beydn was removed from one life support machine after another. It was during these difficult days that the Family decided to create a foundation in Beydn's memory.

"We all agreed that we had to do something," Swink said. "We wanted to fix this -- to help find a cure."

Surrounded by his Family, Beydn died Feb. 22.

Swink said that he could never adequately describe what he felt that day. He was determined to help raise money for pediatric cancer research and for research into invasive fungal infections -- a leading cause of death in patients with compromised immune systems.

"I didn't really know where to start, but I decided if we could help one person -- keep one family from having to go through what we did -- then I would do everything in my power."

See next week's issue of The Mountaineer for part two of Swink's story.

Social Sharing