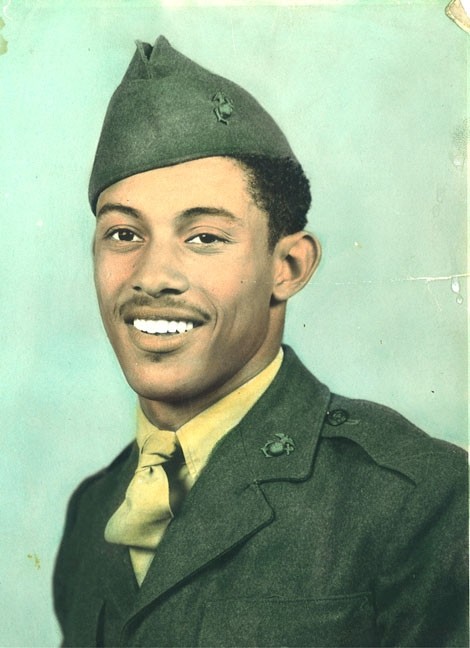

"No longer lean, no longer mean, yet still a U.S. Marine," is Rev. John Baker Brown's motto.

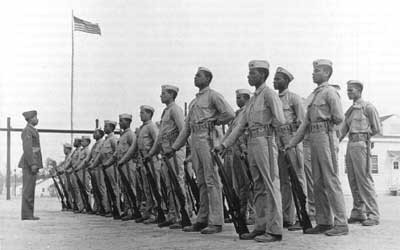

Brown, 84, served five years in the Marine Corps. He was among the first blacks to volunteer, instead being drafted, for service after World War II threatened to engulf the United States. Congress belatedly passed the Selective Service and Training Act in August 1940 - the first peacetime draft. That law forbade discrimination on racial grounds. According to section 4(a) of the Act: "In the selection and training of men under this Act, and in the interpretation and execution of the provisions of this Act, there shall be no discrimination against any person on account of race or color."Montford Point Camp, New River, N.C., was the receiving point for African Americans entering the Marine Corps.

Brown only served five years, but has a vibrant memory of racism and segregation of days gone by.

"A few things played a part of my leaving the service, but my own kind [blacks] played a significant role of my departure," Brown said. "They were meaner than the whites. We took harder knocks from our own than we had expected. The drill instructors felt like they had to be tough by beating us down mentally and physically before bringing us back up, and I didn't want anyone to have that much control over me."

Some recruits saw military service as their big break, a chance for a prosperous future.

"The Marine Corps was good to me and I was good to the Marine Corps," surmised Sgt. Maj. (Ret.) Edgar R. Huff in a videotaped interview before his death in 1994. "They said 'Leave.' I said 'Hell no.' I was going to hold on like a bulldog to a bowl."

Huff, a native of Gadsden, Ala., enlisted in the Marine Corps Sept. 24, 1942. The command structure at camp tried to identify the best of the recruits and place them on a fast track to positions of responsibility in boot camp at the 51st Composite Defense Battalion. In early 1943, Huff became a drill instructor and later the field sergeant major of recruit training at the Montford Point Camp.

As discrimination and segregation ran rampant across the United States, the Marines were making progress by integrating the ranks.

The transition's ups and downs resembled the mountainous terrain of West Virginia with its hills and valleys. While the war built up overseas, the men of Montford Point continued to endure the frustration of being treated as inferior to their white counterparts.

Despite the boundaries, the Marine recruits welcomed the chance to serve with the "toughest fighting force."

Brown originally wanted to join the Army Air Corps and perform foreign embassy duties, but that option wasn't open to blacks. After reading and hearing propaganda about Marines being the fighting force, Brown fell prey to recruiters.

"First we were called the chosen few," said one of the other recruits on the taped interview produced by University of North Carolina Wilmington staff. "It was unbelievable what would lie ahead. We were called out to formation in civilian clothes and marched to the woods miles away from camp and left to find our way back.

"'We don't want you' white Marines would confess," Huff recalled. "'Leave quietly. Go home; nobody will miss you or come looking for you. Don't be here tomorrow; you're not cut out to be Marines. The Marines have been here for years without you being a part of it.'"

Some might consider it a part of the indoctrination, while others believed it was the hatred of blacks wearing the blue uniform, recruits revealed.

"It was hazing to beat and kick us. It was to the extent we couldn't tell anyone," said another one of the original Montford Point recruits. "I made up in my mind I would do it (complete boot camp). I wasn't going home. We wouldn't go away unless they took us out in a box."

The veterans said Marine Corps recruit training was the most difficult thing they ever had to do in their entire lives. In order to train the world's most "elite fighting force," it had to be that way.

One Montford Point recruit recalled memories of the Wailing Wall. There was a water tower in the middle of the training field on camp recruits referred to as the Wailing Wall. Recruits who got in trouble had to run around the tower. Eventually, the repetition of running around the tower created a knee-deep trench.

"Before you left that camp, you'd have spent time wailing there," an old-time Marine said. "I would pray, 'Lord, don't let me be the first one to drop out.'"

Most recruits took the challenge, thinking it wouldn't be more than the "hell" they came through or from at home. Recruits were used to hard work. Some, who left behind their life as share croppers, didn't have much to lose. The Marine life was actually better to them than the dirt roads and outhouses on country farmlands, Huff believed.

Marine recruits lived in green huts with plywood walls and wooden floors. The latrine, with hot and cold running water, was in the center of camp. Each Marine was issued six pairs of underwear, six shirts, two pairs of shoes, ties, slacks and an overcoat.

"Most of those guys never had an overcoat before they got to Montford Point," said Huff. "I left Alabama with 25 cents and knots in my underwear to keep them from looking like a dress," chimed in one original recruit. He was dressed and living good by most standards.

The efforts of white leadership, 30 officers and 90 NCOs, who helped to train the Marines during the 12 weeks of drill, weapons and water survival skills would make the 48 Marine recruits ready to be part of the composite defense battalion.

While the recruits dreamed of jumping off boats with their rifles and charging onto land, ready to pick off the enemy, white leadership had other plans for them; they were conidered "mindless n-words and outsiders, not real Marines. The idea of Negroes wearing the emblem of the Corps was repugnant," according to veterans interviewed.

Some sergeants were threatened by recruits who were college educated.

However, regardless of education levels, most Marine recruits were hustled into work details and used for their brawn, not their brains. When the recruits got to their duty stations, they were given manual labor jobs, such as funeral detailers, transporters for motor vehicles, ammunition carriers, stewards in dining facilities and supply ship loaders and unloaders.

"We were ready to fight. We trained hard and were confident we could do the job," Brown explained. "A sense of honor and duty ran deep. Honor meant going into battle. We wanted to fight for a country that had yet to recognize us as real men. Whole men. Good enough."

"My first assignment was at Washington National Cemetery on funeral detail," said 82-year-old Melvin Shoats, Brown's close friend and fellow comrade. "They put about eight of us on the detail to bury our Marines who returned. We were trained to keep our uniforms polished and ready so we would look good."

Shoats' detail team would bury one Marine in two years. "Even at the cemetery [white Marines] wanted us to wait behind them. They would bury their Marines and then we could go bury ours. When I went to present the flag to a wife, I was surprised she looked white. I thought we may have been burying the wrong Marine," Shoats recalled. "We could be buried next to them, but they wouldn't bury one of us or vise versa."

Despite the trials, scrutiny and challenges, the young Marines faced the ordeals, cemented bonds and built their camaraderie.

In June 1943, the qualifier "composite" disappeared from the designation of the 51st Defense Battalion. The 155mm battery became a group and the machine gun unit evolved into the Special Weapons Group, with 20mm and 40mm weapons, as well as machine guns. Of the 19,168 blacks who served in the Marine Corps during World War II, 12,738, went overseas in the defense battalions or combat support companies or as stewards. More than 2,000 blacks participated in the World War II fight for Okinawa, a larger concentration than for any previous operation, according to Marines in World War II Commemorative Series at www.nps.gov/archive. Marine divisions stormed ashore alongside two Army divisions, while one Marine division engaged in a feint to pin down the island's Japanese defenders. Black Marines also saw action seizing the Mariana Islands Saipan, Tinian and Guam. They also attacked the heavily defended island of Peleliu in the Palau group.

According to the Web site, "black Leathernecks demonstrated they had earned the right to fight alongside their white fellow Marines" when the 34th and 36th Marine Depots laid a field of fire against hidden Japanese, killing 350 of their Soldiers to clear an air strip. After hearing of the heroism of the black enlisted men, Lt. Gen. Alexander A. Vandegrift, commandant of the Marine Corps, declared "The Negro Marines are no longer on trial. They are Marines, period."

"I would do it all again," Brown claims. "If I could have seen the future, I might have stayed longer. So much has changed. We have African American generals and women serving. The military is the most integrated organization. It offers the most opportunities for African Americans than any government agency. I still encourage young people to join, especially those who need discipline."

Today Marines hold the name (Montford Point) proudly and represent their association, recruiting new and old Marines to join them in their fight to carry on that name, said K. Doc Johnson, life member of the Atlanta chapter of the Montford Point Marine Association

"The Montford Point Marines opened the door for all African American Marines." said Johnson, a retired Navy hospital corpsman. "Members of the association join to help preserve the legacy of the original Montford Pointers. Much of the history hasn't been told to others."

For Brown, getting together during association functions is a chance to reconnect with old friends, "some you want to see and some you don't. It's like a family reunion."

Brown and other original Montford Pointers are hailed as "men of wisdom" in the statewide associations. "Their presence among us shows their desire to give back to the younger generations of all branches of the military, to let us know about the struggles and history that may not be accurately portrayed in history books," Johnson said.

The Atlanta chapter of the Montford Point Marine Association meets the third Saturday of each month at 4 p.m. in the Marine Corps reserve Center on Dobbins Air Force Base in Marietta. For more information, call Johnson at 678-575-2154 or send an e-mail message to Linda Sykes, president, Atlanta Chapter, at linasykes@bellsouth.net.

Social Sharing