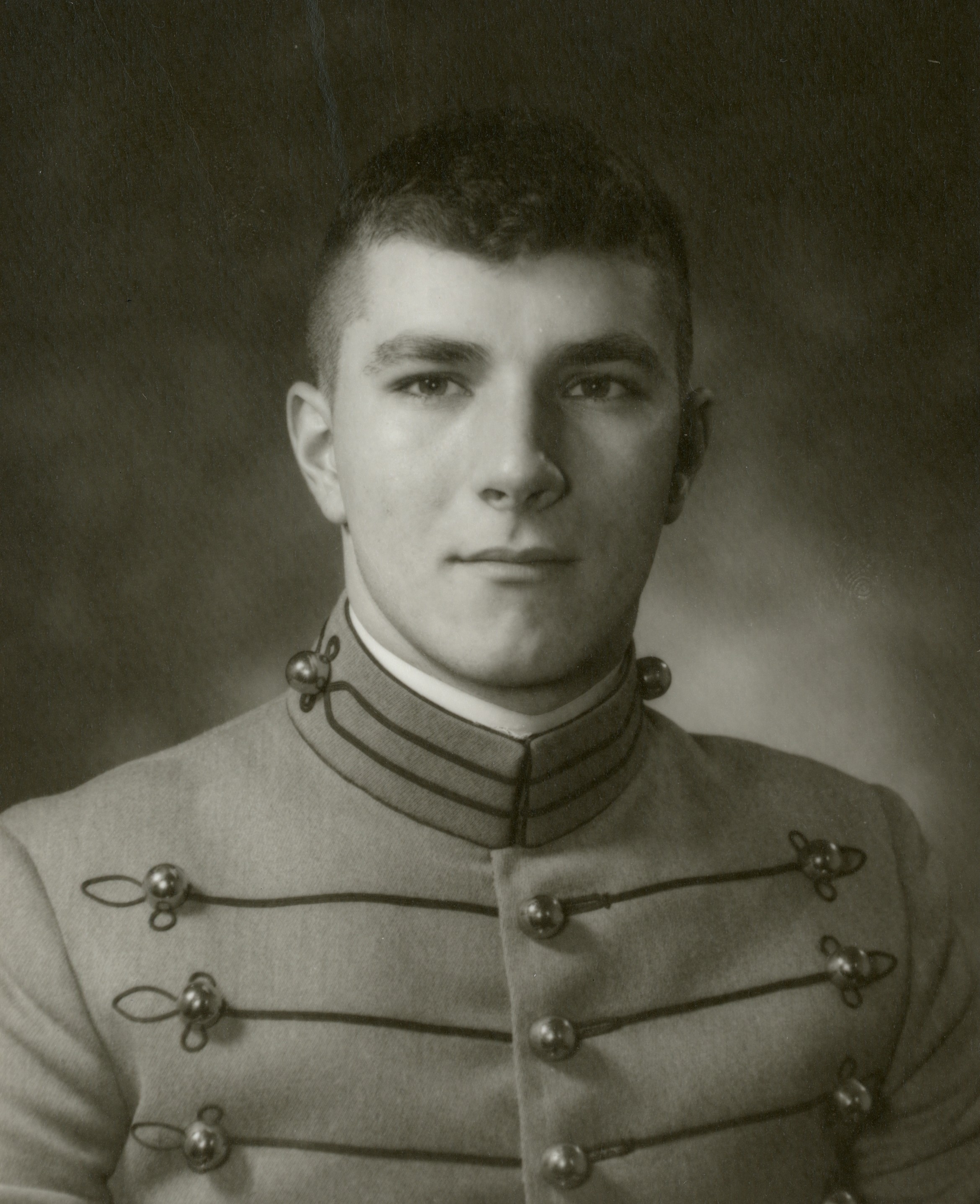

<i>Gen. Richard A. Cody, the 31st vice chief of staff of the Army, retires this month after a distinguished 36-year career. A master aviator who saw combat duty in the Persian Gulf, Cody leaves a legacy of leadership, advocacy for Soldiers and lifelong service to the nation.</i>

You entered West Point during the Vietnam War. What made you want to join the Army during such an unpopular war' Did your family support your decision'

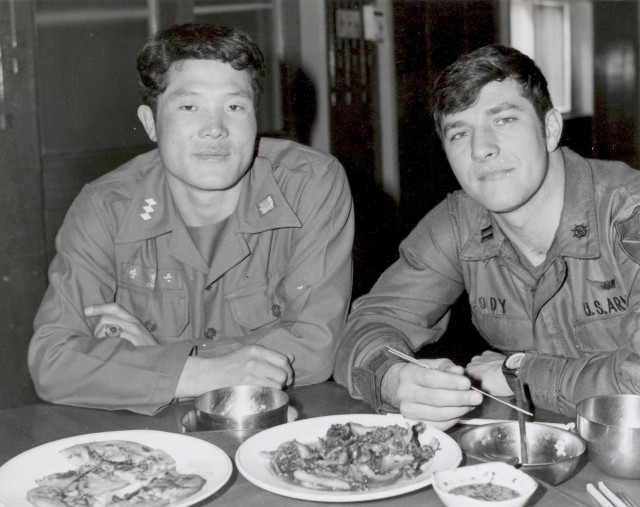

Cody: I was 17 in the summer of 1968. I had a lot of friends who were being drafted, and like everyone, I had been watching the war on TV. Especially the images of the helicopters - the 1st Cavalry Division and 101st Airborne Div. pilots. I just knew I wanted to be an officer and a Cobra pilot.

My parents were concerned about Vietnam. They realized I could be going to combat, but my Dad wanted me to go to West Point. He understood.

It seems the Vietnam War really had an impact in shaping the cadet corps.

Cody: At Thayer Hall they put a plaque up every Friday any time a graduate died in combat. You'd see class of 1966 and 1967, guys that came before us. But it really hit me when George Bass got killed in Vietnam. He was class of 1969 - an upperclassmen when I arrived. I was in his squad as a plebe. He was bigger than life to me. That's when it really hit me - I saw his name go up on that wall and ...well, it really hit me.

But the quality of the instructors was very good - Buddy Bucha, a Medal of Honor recipient from the 101st, was there then. Sy Bunting, a Rhodes Scholar, taught history. They were mavericks. We had guys like that who would be honest, and open a dialogue and talk about what was going right and wrong in Vietnam and in the Army.

You have said that this Army is not broken, that you joined a broken Army. What kind of Army did you graduate into'

Cody: We did not have the redeployment process we have today. There were no mental-health assessments being done, absolutely no attention being paid to families or reintegration. We were experiencing some serious race-relation problems. There were race riots on post - we even had a group of Soldiers take over an entire quad for two or three days. We had a drug problem, mostly marijuana, but other drugs. As a young platoon leader, you had to carry a firearm during staff duty and any time you went into the barracks. The years 1973-1974 were some really tough years, especially from a lieutenant or young captain's perspective.

Did those who stayed believe we could be a better Army'

Cody: Even though the Army was struggling, you saw glimmers of good leadership. When the Army is stressed, good leadership always holds it together. Always. Tough, charismatic, engaged, fearless leadership will hold an organization together. That's what I learned as a lieutenant. That's what made me stay.

I'm seeing the same thing today. That's how we get better. That's why we're the best. I can remember hearing about the All-Volunteer Force concept and believed it was going to transform us.

Those of us who stayed the course and have watched the transformation of this force and had the privilege to be part of it, have been amazed. Not any one person can take credit, it was done collectively. We wanted our Army to be better every day, and we worked on it together.

There was a tendency then to be "zero defect" as the Army was transforming. Some say we could be headed in the same direction. Do you think there are any comparisons'

Cody: We have to be a learning institution. We can't be risk adverse. We have to be disciplined, responsible, and accountable. But, at each level we have to have the maturity and courage to look at something that didn't go right, make corrections in a positive and constructive way, and be able to underwrite honest mistakes.

We are dealing in a stressful combat environment, at an incredible OPTEMPO and with constant media attention. Mistakes will be made, but as long as they don't violate legal, moral and ethical standards, we need to continue to invest and not be "zero defect." We ask Soldiers to be brave on the battlefield; we need to exact that from senior leaders, too. Not being courageous, not exhibiting personal courage to our subordinates and superiors, that doesn't make you better as an Army.

What gives you courage as a leader' How do you balance the ego it takes to be a leader, to make the tough decisions, but still have the humility you do with Soldiers'

Cody: You have to have confidence in what is right. I don't know if that's ego or not, I'm not a philosopher. I know that as a leader, you have to have love of soldiering and Soldiers first and above all. Second, you have got to have confidence. None of the decisions a leader makes should be easy. If I think it's the right decision, it's OK if it's unpopular and people don't like me. This isn't a popularity contest. Respect for this institution is very important, and sometimes has to supersede personal likes and dislikes.

We are a team. If you allow ego to reign, emotion will trump true leadership. You'll have a clash of egos instead of a discussion about skill sets, capabilities and what is good for the organization. Some of this is cerebral, but hell, a lot of it is about the heart. It's about putting yourself out there, warts and all, as a rallying point for the troops. Soldiers don't care if you're smart; they give you the benefit of the doubt as a leader. They want to know if you can tell a joke that's actually funny; if the job you have now is more important than the one you might have tomorrow; and that you love them, the unit and this Army.

Why do you think Soldiers are staying with the Army today, despite the stresses we have'

Cody: First of all, this is absolutely the best Army we've ever had. There is not a time in my 36-year career when we have been better. But we have lost far too many captains and mid-level NCOs who would have stayed because they love the Army, but because we could not grow fast enough and the demands on our force are outstripping supply, had to choose between the Army they love and the families they love.

They should not have to make that choice, and that's why we're working so hard to grow this Army, get it in balance, get to the 1:2 and 1:5 deployment ratios. We stay because we have a sense of duty, honor and country that even when you get tired, when you lose friends or are frustrated by bureaucracy, can't be compromised. We stay because the Army isn't a job, it is a larger family that your own family is defined and sustained by. We stay because we look out there and say, if not me, who'

I know you are going to miss the Army. Do you think the Army will miss you'

Cody: This Army won't skip a beat on the day I retire. That's a good Army. That means there's good leadership, that the institution is strong and will persevere. I will take this uniform off, and I will live the Army life through my sons and nephews. There will still be five Codys in the Army. And I will continue to ask myself, like I do every day on my way home as I make that turn into Fort Myer and am greeted by the white headstones of Arlington: "Am I doing everything I possibly can to support our Soldiers serving today'

"Am I showing the same moral courage, the same bravery in my job that I saw every day in the eyes of our Soldiers' "Am I living my life as an American to be worthy of their sacrifice'"

<i>It was brought to the attention of the Sodiers magazine editorial staff that in the original version of this interview, the introductory paragraph incorrectly stated that Gen. Cody served in combat in Vietnam. Although the error has been corrected in the current version, Soldiers offers the following correction and apology:</i>

The former Army Vice Chief of Staff, Gen. Richard A. Cody (ret.), called to our attention an error in his farewell story, featured on pages 28 through 31 in the August issue of Soldiers.

The opening paragraph of the article read, Aca,!A"A master aviator who saw combat duty in both Vietnam and the Persian GulfAca,!A|Aca,!A? Gen. Cody stressed that he never saw combat in Vietnam, nor has he ever made any claims of that nature or worn any Vietnam combat ribbons.

Gen. Cody served with honor and commitment throughout his 36-year career, and has never claimed distinctions to which he is not entitled.

The Soldiers editorial staff accepts all responsibility for the misrepresentation, and offers its sincerest apologies to Gen. Cody and his family for the error. We wish Gen. Cody and his family all the best in their future endeavors, and thank them for their tireless service to Army and country.

Social Sharing