FORT JACKSON, S.C. -- On Sept. 11, 2001, confusion was the rule of the day in New York City.

Chaos is to be expected when two of the tallest buildings in America come crashing down. There were questions that needed to be answered, but the answers weren't coming quickly enough in the weeks that followed the attacks, said Capt. Anthony Soika, commander of Headquarters and Headquarters Company, Army Training Center and Fort Jackson.

"What was shocking to me was that people from all over the country instantly reacted to the crisis," Soika said. "By Sept. 13, Ground Zero had become so crowded by people trying to help, that nobody could get anything done. It was like a mosh pit for 50 acres."

The solution to the problem angered some people, which was probably unavoidable. Anybody who wasn't a formal representative for emergency services was quickly pushed outside of the perimeter of Ground Zero.

"A lot of people were pretty upset. There were people there from Florida, and I met cops from Phoenix, Az.," he said. "And this was just 48 hours after the fact. I thought that was shocking, that someone dropped everything they were doing, jumped in a car and drove from Arizona to New York to see if they could help. It was really heartbreaking to say, 'No, you can't help.'"

Soika hadn't been in New York for very long before Sept. 11. He had completed Basic Combat Training at Fort Jackson in 1989 before moving on to Explosive Ordnance Disposal school. He was deployed in Operation Desert Storm, leaving active duty in 1994 to join the National Guard and return to college.

With degrees in exercise science in hand, he took a job as director of physical fitness at the U.S. Merchant Marine Academy in New York.

"You don't start out as Steve Spurrier, you've got to climb the ladder," he said of the academy coaching position. "Every morning, we had remedial physical education for the students who couldn't pass the PT test. My battle rhythm each day was, I came in to do remedial PE at 5:30 a.m. for an hour, then went home and came back around 9 or 10."

When he returned to work on the morning of Sept. 11, he had been listening to a Jimmy Buffet album in his car and missed the news reports of the first airplane to crash into the World Trade Center. He said he had not adjusted well to the inherit hostility of New Yorkers, and Buffet was a way to escape for a few minutes of the day. He said the city made him a "Parrothead."

"When I got to the academy, a good friend of mine, who was a Coast Guard officer, started to make a call on his cell phone," Soika said. "It was widely known by the people who worked there that you couldn't get cell reception on the academy grounds. I mentioned that as I got out of my car, and he blurted out, 'My wife works at the World Trade Center.' My exact words were, 'What does that have to do with anything?'"

He was told a terrorist had crashed an airplane into the twin towers. Even then, he said, he had trouble imagining the magnitude of what was happening.

"In my head, I'm thinking somebody stole a Cessna and crashed it into the building. I said she was probably fine," he recalls. "The building's gargantuan, and what's a Cessna going to do? What are the odds it's that exact office?"

When he arrived at the academy's athletic department, he found the office was a "ghost town."

"I thought there was a meeting I had forgotten about," he said. "I went to the conference room and, sure enough, everyone was there. But they were hovering around the TV in the corner of the room. Just as I go over to look, the second plane hit the other tower."

The academy is located on the shore of Long Island Sound, and the smoke from the attacks was visible from the window, Soika said. "You could see the smoke being carried by the wind a thousand feet above the ground," he said. "We were all in shock."

Minutes later, Soika received a telephone call from his National Guard unit advising him to prepare for duty. His guard unit was a three-hour drive from the academy on Staten Island.

"All the roads were in complete gridlock," he said. "I drove mile after mile on the side of the road and through ditches with my hazard lights on."

He arrived with his unit in Manhattan around 2 a.m.

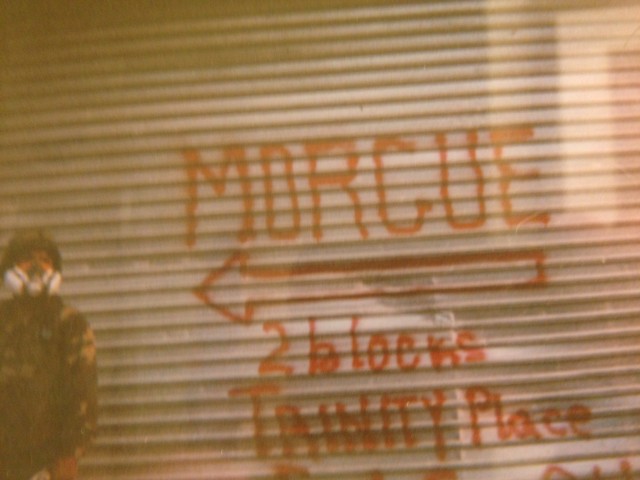

"By the time the sun came up, the orders I had were to take my crew, which was a Humvee and four Soldiers counting myself, and secure the intersection at Walker and Broadway," he said. "They were very vague orders. The last orders I got were not to let anyone into lower Manhattan. It's a very wealthy part of Manhattan and there was a lot of concern about looters. They were evacuating lower Manhattan in case there was a dirty bomb or other issues. But, if you clear the wealthy out of lower Manhattan you leave a vacuum of people who know very well that they can take whatever they want."

At the scene were 40 police officers from a dozen precincts who had been given the same orders.

Among those volunteering during the recovery was a professional football player who was easily recognizable to New Yorkers, but not so much to Soika, a Minnesota native.

"Late on the morning of Sept. 13, I see this Italian, Rocky-looking guy making his way through the crowd," he said. "I remember thinking, 'Where does he think he's going?' He looks at me and walks on by like I'm not even there."

He grabbed the man's arm, prompting an immediate response from a police officer.

"Before he could react, a NYPD cop approached and said, 'He's with me.' We're working 21-hour shifts, and I'm exhausted," Soika said. "Someone turns to me and says, 'Do you know who that was? That was Vinny Testaverde, a quarterback from the New York Jets. Well, he should have worn a name tag."

Soika spent 15 days at Ground Zero, and was later activated for another 90 days for service in New York City. The second time was to help manage security on the Brooklyn side of the Manhattan Bridge.

"We were told to stop any 'major vehicle' going into the city," he said. "Well, what's a 'major vehicle?' ... They were stopping all the taxi cabs that came in, and 99 percent of the taxis in New York are driven by Arabic people. We had to search every taxi, every cargo vehicle, every van ... if it wasn't a car or a pick-up truck, it got searched."

He said the goal was to prevent terrorists from following up on the first attacks, but the strategy proved to be a hollow "show of force." The traffic subjected to searches was mostly made up of local employees trying to get on with their lives.

"At the other end of the bridge was Chinatown, so most of the vehicles that we searched were driven by small businessmen from Chinatown trying to deliver chicken to a restaurant, and they didn't necessarily speak English," he said. "I learned early that 'xie xie' was Chinese for 'thank you.' It really smoothed a lot of ruffled feathers. Instead of being the ugly American, it let them know we felt bad for holding them up for nothing."

Semi-trucks were required to have manifests for their cargo, which had to be verified before they were allowed to pass the blockade, he said. One truck that tried to cross the barrier was carrying a 55-gallon drum of an unidentified white powder that had spilled.

"The driver either didn't speak English, or was acting like he didn't speak English," Soika said. "And he had no manifest. You can't do a U-turn at the foot of a bridge, and he sure as hell wasn't going over the bridge. It fell upon me as an NCO to make a command decision. The driver hasn't done anything wrong, but I can't send him on with potential anthrax, and there was nobody senior to me to defer to. So I turned to my (private) and said, 'Train your weapon on this guy. If anything happens to me, kill him.'"

Soika took a taste of the white powder. When he didn't immediately fall ill -- or worse -- he allowed the driver to pass the barricade.

"My mom hates that story," he said.

From day to day, Soldiers weren't sure of how long their presence would be required in New York. In the end, Soika spent 28 days in New York City before returning to work at the academy.

"We were infantrymen," he said. "Directing traffic and searching cabs, that's not what we do. We've all heard of Soldiers who don't want to deploy. This was a case where these were New Yorkers, this was an attack on New York, it was personal and they wanted to go. Every single one of them would rather have deployed to Afghanistan for a year than spend 38 days downtown. I was really impressed by that."

Social Sharing