CHAPTER XIX The Battle of Bastogne The Initial Deployment East of Bastogne The one standing order that General Middleton gave General McAuliffe before leaving Bastogne on the morning of 19 December was: "Hold Bastogne." * Both generals felt that the enemy needed Bastogne and the entrance it afforded to a wider complex of roads leading west. (Map VI) During the night of the 18th the two commanders met in the VIII Corps command post to confer on the uncertain tactical situation and to give Colonel Ewell, whose regiment would first be committed, his instructions. The map spread out before Ewell showed a few blue-penciled marks east of Bastogne where the American armored groups were believed to be fighting at their original roadblock positions. General Middleton told Ewell that his job would be to make contact with these endangered forward posts. Ewell, however, was interested in the red-penciled lines and circles which showed the enemy between Bastogne and the armored roadblocks. In view of the uncertain situation, he suggested that he be given "mission-type orders" which would permit his 501st Parachute Infantry some flexibility of action. McAuliffe agreed, as did Middleton, but the latter still hoped that the roadblock defenders at Allerborn, eight miles to the east on the Bastogne road, would somehow survive until the 501st reached them. McAuliffe's order, then, was for Ewell to move out at 0600, attack eastward, and develop the situation. At the appointed hour on 19 December Ewell's 501st Parachute Infantry marched out of the assembly area in column of battalions. Ewell knew that this was no time to engage in the all-out, full-bodied assault tactics to which the paratroopers were accustomed. He told [445]

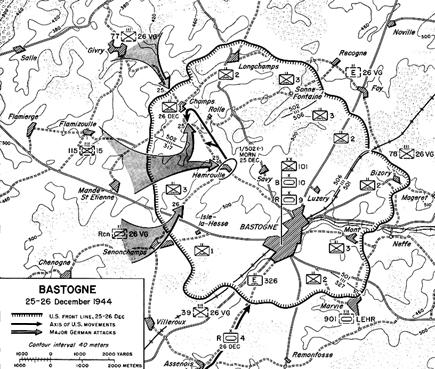

BASTOGNE [446-447] his officers to "take it easy," avoid commitment to an action which would involve their whole force, and deploy to right and left as soon as they hit resistance so that they would not be easily cut off and surrounded.1 Hindsight, of course, bestows a view of the American and German dispositions at 0600, when the 101st advance guard marched out, which was denied Ewell and the corps and division staffs in Bastogne. The battles already described were now coming to a close on the roads, in the villages, and through the woods east of the town as the 101st was taking its stance. During the night of 18 December the three small task forces of CCR, 9th Armored Division, which Middleton had ordered Colonel Gilbreth to position on and overwatching the Allerborn-Bastogne road (N 12), were cut to pieces. Some men and vehicles would escape to take a part in the fight for Bastogne, although some of Colonel Booth's command took six days of dodging the enemy before they reached the American lines. At Longvilly, next, and to the west, on the Bastogne road, Gilbreth had gathered what was left of CCR and its attached troops to fight a rear guard action until the 19th dawned and an orderly withdrawal might be effected. Gilbreth started his guns displacing to the rear some time before daybreak, but the main force commenced to defile through the western exit from Longvilly about 0800, only to be ambushed and thrown into disorder when approaching Mageret, midway between Longvilly and Bastogne. Team Cherry (Lt. Col. Henry T. Cherry) of CCB, 10th Armored Division, which had been sent along the road toward Longvilly the previous evening, found itself involved in a series of disjointed actions as enemy troops cut the highway. Team Hyduke (1st Lt. Edward P. Hyduke) was caught up in the fight east of Mageret, subsequently losing all its vehicles in a sharp and aggressive armored action which the 2d Panzer commander dignified as an American "counterattack." (Late on the afternoon of the 19th Lieutenant Hyduke led his men on foot out of the melee under orders to rejoin CCB. He was afterward killed at Bastogne.) Team Ryerson (Capt. William F. Ryerson), the main force belonging to Cherry, had laagered during the night between Mageret and Longvilly-and thus would fight an action almost independently of the Longvilly column-but before daybreak Ryerson knew that the enemy was in Mageret and that he would have to punch his way back to the west. Cherry sent orders confirming this withdrawal about 0830. Ryerson found his team outnumbered and outgunned by the Germans holding Mageret, but on the night of the 19th four squads of his armored infantry held a narrow foothold in a few houses on the eastern edge of the village, waiting there for help promised from the west. Colonel Cherry had gone back to Bastogne to see the CCB commander late on the 18th, returning [448] thereafter to his own headquarters outside Neffe (a mile and a quarter southwest of Mageret) with word that the 101st would reinforce his command the next day. On the road back, however, he learned that the Germans were in Mageret and his troops were cut off. About the time Ewell's paratroopers debouched on the Bastogne road, Neffe was hit by tanks and infantry from Panzer Lehr; some hours later Cherry's detachment would pull back to Mont.2 On the morning of 19 December, therefore, the job confronting the 501st was that of developing, fixing, and fighting the German detachments, now in strength, which stood to the rear of the erstwhile American blocking positions and presaged the coming main effort to crash the panzer columns through or around Bastogne. The German High Command was aware that the two American airborne divisions had orders to enter the battle; in the late afternoon of 18 December intercepted radio messages to this effect reached OB WEST. German intelligence knew that the Americans were moving by truck and so estimated that none of these new troops would appear in the line before noon on the 19th. The German staffs believed that the two divisions would be deployed along a front extending from Bastogne to the northeast. In any case the German attack plan was unfolding about as scheduled and three German divisions were bearing down on Bastogne. The 2d Panzer Division's successes during the night of 18 December against the outpost positions east of Longvilly had netted forty American tanks, and the apparent crumbling of the last defenses east of Bastogne promised quick entry to that city on the 9th. Actually the three German divisions moving toward Bastogne were not all maneuvering to attack the city. Lauchert's 2d Panzer Division had other fish to fry-its objective was the Meuse bridges-and when daylight came on the 19th the division advance guard was working its way to bypass Bastogne in the north. The 2d Panzer's end run, across country and on miserable third-class roads, collided with Maj. William R. Desobry's task force from CCB at Noville (four miles north of Bastogne), then blundered into a series of sharp actions reaching back to Longvilly. On the left the Panzer Lehr, having seized Mageret during the night, began an attack about 0500 on the 19th designed to take Bastogne; it was a part of this forward detachment of Panzer Lehr which hit Cherry's headquarters at Neffe. Close on the heels of Panzer Lehr, two regiments of the 26th Volks Grenadier Division had made a right wheel with the intention of circling through Longvilly and Luzery so as to enter Bastogne from the north via the Noville road. Kokott's grenadiers, who had accomplished a truly remarkable feat in keeping pace with the mechanized columns of the Panzer Lehr, by now were spent. The regimental trains were far to the rear and resupply had to be made. Furthermore the boundaries and attack plans for the three divisions converging [449] on Bastogne were so confused that it would take some time for the 26th Volks Grenadier Division (-) to orient and coordinate its attack. On the morning of the 19th Kokott's two regiments lay quiescent and exhausted in the scattered woods southeast of Longvilly. Only the advance guard of the Panzer Lehr, therefore, was attacking directly toward Bastogne when the paratroopers of the 501st marched on to the Bastogne-Longvilly road.3 Ewell had his 1st Battalion (Maj. Raymond V. Bottomly, Jr.) out as advance guard. The road was curtained at intervals by swirling fog and from time to time rain squalls swept in. Some 2,000 yards out of the city (it now was about 0820) the battalion ran onto a few howitzers from the 9th Armored whose crews were "ready, willing and able," as the journals report it, to support the 501st. Less than a thousand yards beyond, the advance guard encountered the enemy near the railroad station at the edge of Neffe; here was the roadblock which the Panzer Lehr had wrested from Cherry's headquarters detachment. On the previous evening the VIII Corps commander had sent the 158th Engineer Combat Battalion (Lt. Col. Sam Tabets) to establish a line east of Bastogne between Foy and the Neffe road. Nearly a thousand antitank mines had been scraped together from other corps engineers to aid the 158th, and at least part of these were laid in front of the engineer foxholes during the night. When the 158th reported about 0200 that its outpost at Mageret had been overrun, Middleton sent what help he could-five light tanks taken from ordnance repair shops. At daybreak two enemy rifle companies, led by a few tanks, hit Company B, whose right flank touched the Bastogne highway near Neffe. The engineers succeeded in halting the advance along the road, although at a cost of some thirty casualties. Pvt. Bernard Michin seems to have blocked the panzers when he put a bazooka round into the leader at ten yards' range. Meanwhile Team Cherry had lost its roadblock at the Neffe station but momentarily had stopped the Germans at Neffe village. Enemy pressure then eased somewhat; perhaps the German infantry were waiting for their tanks to break through at Mageret. The fight had slackened to a small arms duel when Ewell's paratroopers came on the scene.4 Feeling carefully to the north and south of the highway, the 1st Battalion found that the Germans were deployed in some force and that this was no occasion for a quick knockout blow to handle a single roadblock. About 0900 Ewell turned the 2d Battalion (Maj. Sammie N. Homan) off the road in a maneuver on the left of the vanguard intended to seize the higher ground near the village of Bizory and Hill 510, a fairly substantial rise to the east which overlooked both Neffe and Bizory. When the 3d Battalion (Lt. Col. George M. Griswold) [450] came up, Ewell sent it to the right with orders to take Mont and the ridge south of Neffe. By noon the regimental attack had attained most of its objectives. (Bizory already was outposted by troops of the 158th Engineer Combat Battalion.) Hill 510, however, was no easy nut to crack. The enemy held the position with automatic weapons sweeping the bare glacis to west and south-here the paratroopers made no progress. On the right one of Griswold's platoons arrived in time to give Colonel Cherry a hand in the fight at the Neffe château command post and, when the Americans were burned out, the subsequent withdrawal to Mont. The 3d Battalion had not been able to get around Neffe, but Company I did go as far as Wardin, southeast of Neffe, where it ambushed a 25-man patrol. The appearance of the Americans in this area, little more than a mile south of Mageret, was interpreted immediately as a flanking threat to the two grenadier regiments of the Panzer Lehr which had wheeled to the right and away from Bastogne to engage the American columns transfixed on the Mageret-Longvilly road. Bayerlein detached a part of his reconnaissance battalion to meet this threat. The Americans made a fight of it inside Wardin, retreating from house to house as the long-barreled self-propelled guns blasted in the walls. One paratrooper walked into the street to confront one of the guns with a bazooka; he got the gun, then was cut down. Finally the guns jolted the paratroopers out of Wardin; they had inflicted thirty-nine casualties on Company I, all of whose officers were hit, and killed Capt. Claude D. Wallace, Jr., the company commander. To the west, near the hamlet of Marvie, lay the tanks and armored infantry of Team O'Hara (Lt. Col. James O'Hara) holding the right of the three blocking positions set up by CCB, 10th Armored, the day before. O'Hara thus far had seen no Germans. His first warning that the fight was expanding in his direction was the "stragglers of airborne around us" and high velocity shellfire directed at his left tank platoon. For some reason the enemy failed to close with O'Hara, perhaps because of the low, clinging fog which had reduced visibility to about seventy-five feet. Ordered to do so by Colonel Roberts, the CCB commander, O'Hara sent tanks back into Wardin, but the village was empty. The tanks retired to the Marvie position as dark came on, and late in the evening Panzer Lehr occupied Wardin. A message from McAuliffe ended this initial day of battle for the 501st and the regiment dug in where it stood. Ewell now had a fair picture of the enemy to his front but no clear idea of the fate or location of Team Cherry's main force, not to mention the CCR roadblock detachments. Although the 501st had deployed successfully astride the main road east of Bastogne and had developed a sketchy outline of the most advanced German positions, it had not at any time confronted the main German forces. These, the bulk of Panzer Lehr and the two forward regiments of the 26th Volks Grenadier Division, spent most of the day chopping down the American column trapped between Mageret and Longvilly. Kokott apparently had expected to push his two grenadier regiments unopposed through Longvilly, as soon as they were rested, in a circling march to [451] enter Bastogne from the north, but the German corps commander, General Luettwitz, himself took these regiments out of Kokott's hand and thrust them into the battle with the American rear guard at Longvilly-which held there longer than expected-and against the retreating column en route to Mageret. Suffice it to say that the 501st had been effectively debarred from the Longvilly arena by the Panzer Lehr troops holding Neffe, Hill 510, and the stopper position at Mageret. By the evening of the 19th the American troops east of Mageret were in varying stages of tactical dissolution-all but Team Ryerson, still clutching its piece of Mageret village. Luettwitz was elated by this victory over the American armor (which as an old tanker he attributed in large part to the superiority of the Panther tank gun), but he realized that a precious day had been lost and with it the chance of an armored coup de main at Bastogne. At Noville, the left of the three blocking positions, Middleton had assigned Colonel Roberts and CCB. Here Team Desobry, organized around fifteen medium tanks, stood athwart the main paved highway running north from Bastogne to Houffalize. This force had been in position about five hours, reporting all quiet, when at 020 on the 19th German half-tracks hit the American roadblocks. Americans and Germans pitched grenades at each other in the fog and one or two panzers reached the village itself. The enemy-probably a patrol feeling a way in front of Lauchert's 2d Panzer-soon pulled out, and the noise of battle died away. The VIII Corps commander, much concerned by the gap which he knew existed between his southern troops and those of his corps somewhere to the north, ordered Desobry to investigate the town of Houffalize. (During the night, a patrol Desobry had sent in that direction reported the road open.) Before anything could be done about the Houffalize mission, the Germans unleashed their artillery against Noville. Lauchert, intent on regaining the momentum which the 2d Panzer had lost in the night fighting around Allerborn and Longvilly, and determined to get off the miserable side roads which he had chosen as a quick way around Bastogne, put all the guns that had kept pace with the forward elements into a shoot to blast a way through to the west. At 1000 the fog curtain suddenly parted revealing a landscape dotted with German tanks-at least thirty of them. Fourteen tanks from the 3d Panzer Regiment made a try for Noville, coming in from the north. Several bogged down in a vain attempt to maneuver off the road; others were slopped by Desobry's company of Sherman tanks and by tank destroyer fire. On the east the enemy had started an infantry assault, but the fog lifted before the first waves reached the village and, suddenly divested of cover, most of the attackers turned and ran. Desobry could not know that Noville was the focus of the entire 2d Panzer maneuver, but he did ask for permission to withdraw. Roberts replied that Desobry should use his own judgment, then added that more tank destroyers were on the way from Bastogne (Desobry had only a platoon from the 609th) and that the 101st was sending a rifle battalion within the half hour. Coincident with Roberts' message the last of the German assault force pulled back. Lauchert had decided that the ground was too poor [452] for tank maneuver, that reinforcements must be brought up for a headlong plunge. Meanwhile the German cannoneers continued to pummel Noville. Desobry had many casualties, but several ambulances had been wrecked by shellfire and it was difficult to get the wounded out. The reinforcements reaching Desobry consisted of a platoon from the 705th Tank Destroyer Battalion (three companies of which constituted the only corps reserve Middleton had to give the 101st Airborne) and the 1st Battalion (Lt. Col. James L. LaPrade) of the 506th Parachute Infantry. Although McAuliffe assigned the 506th the mission of covering the northern approaches to Bastogne, the remaining two battalions had a string attached as the division reserve, and the regimental commander, Colonel Sink, was under strict orders not to move them from their positions just north of Bastogne. As the paratroopers approached Noville, they came under heavy, well-aimed artillery fire, twenty to thirty rounds exploding on the village every ten minutes. Vehicles and buildings were aflame-this was indeed a hot corner, the village itself practically bare of life. Desobry's detachment was deployed south and west of the village; the Germans were firing from the north and east, a more comfortable position since the higher ground encircling Noville tilted up on the enemy side of the dish. By 1430 the 1st Battalion was ready to begin the assault against the enemy-held high ground. The center company walked almost immediately into a rain of barrage fire and was stopped with heavy losses. The two remaining companies were met with intense small arms fire but in fifteen minutes worked their way forward in short spurts to a point where one last dash would put them on the crest. As the paratroopers lay here, a mass of green-clad figures suddenly erupted over the hill. Later the 1st Battalion estimated this attack was carried by a rifle battalion backed by sixteen tanks. The American assault had smacked headlong into the attack the 2d Panzer had been readying since mid-morning. As the fight spread, nearly thirty-two panzers were counted on the field. The two antagonists each reported subsequently that "the enemy counterattack halted." Both probably were correct-although both continued to suffer heavy casualties. The German tanks might have decided the issue, but for over half an hour they stayed well back of the rifle line, perhaps fearful lest bazooka teams would reach them in the smoke and fog billowing up the hill, perhaps fearful of the bite in the few Shermans left. When a few of the enemy tanks finally ventured to approach, the American tank destroyers south of the village got on the flank of the panzers and put away five of them at 1,500-yards range. Now as the smoke and fog increased, only small eddies broke the pall to give a few minutes of aimed fire. Two of the airborne companies fell back to the outskirts of Noville while the third, on the hill to the east, waited for darkness to cover its withdrawal. At one juncture the 1st Battalion was under orders to leave Noville, but Brig. Gen. Gerald J. Higgins, the assistant division commander who was acting alter ego for McAuliffe, told the paratroopers to stay put and promised assault gun and tank destroyer support for the morrow. To the Noville garrison the dark [453] hours were a nightmare. Every half hour a gust of enemy artillery fire shook the town; one shell crashed near the American command post, killing LaPrade and wounding Desobry. Maj. Robert F. Harwick, a paratrooper, assumed overall command, while Maj. Charles L. Hustead replaced Desobry as the armored team commander. (Desobry, with an agonizing head wound, was placed in an ambulance headed for Bastogne, but the ambulance was captured en route.) Through the night the panzers prowled on the edge of the village and the German grenadiers came out of their foxholes in abortive forays to reach the streets. But the paratroopers held the enemy at arm's length and the enemy tankers showed little inclination to engage Hustead's remaining eight Shermans, which had been brought into the village, in a blindfold duel. Earlier in the day the 101st commander had planned to establish a defensive line running northwest to southeast in front of Bastogne from which the 501st, tied in with Desobry and Cherry as flank guards, would launch a counterattack. The events of the 19th, as it turned out, showed how little room for maneuver was left the Americans. Colonel Roberts, assessing the reports from CCB in the early evening, advised McAuliffe that "right now the whole front is flat against this town [Bastogne]." Roberts was right; nonetheless there remained two indentations in the fast-forming German line: the thumb sticking out at Noville and Team Ryerson's little enclave on the east edge of Mageret. The latter, however, disappeared during the night hours, for Ryerson, on orders, circled the enemy troops in Mageret and brought his depleted command into the lines of the 501st at Bizory. (Ryerson later was killed at Bastogne.) General Luettwitz lacked the full German corps he craved to throw against Bastogne on the 20th. The 26th Volks Grenadier Division could count on only two of its regiments. Panzer Lehr had a substantial part of the division immediately east of Bastogne, but at least one infantry regiment, much of its artillery, and the bulk of the division trains were still toiling along the gummy little roads -hardly more than trails-climbing west out of the Wiltz valley. Furthermore, Luettwitz had ordered Bayerlein to hold out a reserve for a dash toward Sibret. The neighboring corps might lend Luettwitz a hand in the north-after all its 2d Panzer either had to break through at Noville or had to retrace its steps-but the Fifth Panzer Army commander had reiterated in no uncertain manner that Lauchert's goal was the Meuse, not Bastogne. The entire artillery complement of the 2d Panzer was in place to support the attack at Noville when the 20th dawned. Lauchert's armor was in poor repair after the long and rough march A goodly number of tanks had been shot up in the first day's action at Noville, and the combination of muddy terrain and American antitank fire boded no good for a headlong armored assault. Lauchert therefore told his panzer grenadiers to carry the battle in company with small tank packets. While the German guns plastered the village the grenadiers moved in about 0530 on three sides. Smoke and swirling fog veiled the attackers but the 420th Armored Field Artillery Battalion, firing from northwest of Bastogne, laid down a protective curtain which held the enemy [454] at bay for over an hour. The eight Shermans by this time had run out of armor-piercing ammunition and half a dozen panzers tried to close in. A fresh platoon of tank destroyers from the 705th Tank Destroyer Battalion, sent up by Higgins, took a hand and broke up this sortie. In midmorning, when a promised platoon of quad mount antiaircraft failed to appear, Harwick and Hustead learned that the enemy had cut the road to the rear. The two aid stations could handle no more wounded-most of the medics and aid men were casualties-and the enemy grip obviously was tightening. The word relayed through the artillery net back to Bastogne told the story: "All reserves committed. Situation critical." McAuliffe and Roberts consulted, agreed that the Noville force should withdraw. To free the troops in Noville would take some doing. General Higgins, in charge of the northern sector, already had acted to meet this crisis by sending the 3d Battalion of the 502d Parachute Infantry (assembled near Longchamps) into an attack northeast against the Germans who had descended on the road linking Noville and Foy. The latter village, 2,500 yards south of Noville on the Bastogne road, had been occupied by the 3d Battalion of the 506th, which had its own fight going. Foy lies at the bottom of a pocket and during the night elements of the 304th Panzer Grenadier Regiment had wormed their way onto the hills overlooking the village from north, west, and east. With this vantage the Germans brought their direct fire weapons to bear and forced the 3d Battalion back onto the high ground south of the hamlet. But by noon the 101st had a solid base for a counterattack. The 2d Battalion of the 506th covered the right flank of the 3d and was in contact with the 501st on the east. The battalion sent from the 502d was in position west of Foy. Beginning the counterattack at 1400, paratroopers pushed back through Foy and dug in some 200 yards to the north where late in the afternoon they met the column fighting its way back from Noville.5 The smoke and fog that run through all reports of the Noville fight did good service as cover when the Americans formed for the march out. The main German barrier force had arrayed itself just north of Foy, complete with armor and self-propelled guns. Four Shermans, in the van with a few half-tracks, were put out of action before they could return fire. While one paratroop company attacked to open the road, Major Harwick sent for two tank destroyers from the rear of the column. Shells were bursting among the troops crouched by the roadside, and the clank of tank tracks could be heard approaching from Noville. But the tank destroyers and their armor-piercing shell did the trick-and an assist must be credited also to the Americans in Foy who were now on the enemy's rear. By 1700 the column was back inside the American lines. The fight at Noville cost the 1st Battalion of the 506th a total of 13 officers and 199 men killed, wounded, and missing. Team Desobry has no record of its casualties but they must have been very heavy, both in men and vehicles. The 506th estimates that the 2d Panzer lost thirty-one vehicles in the Noville fight [455] and perhaps half a regiment of foot. At least the first part of this estimate may be close to the fact, for it is known that one battalion of the 3d Panzer Regiment was badly crippled at Noville. There is an epilogue. In late afternoon, as his soldiers poked about the ruins of Noville, Lauchert radioed the LVIII Panzer Corps commander for permission to wheel the 2d Panzer into Bastogne. Krueger's answer was prompt and astringent: "Forget Bastogne and head for the Meuse!" The attack planned for the 19th east of Bastogne and carried out by the Panzer Lehr and 26th Volks Grenadier Divisions had signally failed of success. The soft ground had made it impossible for the German tanks to maneuver easily off the roads-a factor of great worth to the defenders. The Americans had at least five artillery battalions on call in this sector, whereas neither of the two enemy divisions had been able to get any substantial number of guns and howitzers forward. Also, the pellmell, piecemeal deployment east of Bastogne by the advance guard formations was beginning to reap a harvest of delay and tactical confusion. There was some savage fighting here during the day, but uncoordinated-on the part of the enemy-and never pressed in force to a definite conclusion. On the 20th Luettwitz turned the 78th Volks Grenadier Regiment over to the Panzer Lehr commander for the close-in northern hook at Bastogne planned for execution the previous day. The immediate goal was Luzery, a suburb of Bastogne on the Houffalize highway. The 78th circled north to pass the village of Bizory, the left wing pin for the 501st, but fire from Company F caught the Germans in the flank. This halted the move and forced the 78th to swing wide into the cover given by the woods north of the village. Masked by the woods the enemy proceeded west as far as the Bourcy-Bastogne rail line, then unaccountably stopped. When the 2d Battalion of the 506th came up on the left of the 501st, its disposition was such that it faced this German force, plus its sister regiment the 77th, at the point where the Foy-Bizory road crossed the railroad. Through most of the daylight hours on the 20th the enemy seemed content to probe the main line occupied by the 501st. During the evening Bayerlein sent his own 902d Panzer Grenadier Regiment against Neffe, but a roving patrol from Team O'Hara happened to spot the tank detachment of the regiment as it filed along the Neffe-Wardin road and brought friendly artillery into play. Between the American gunners and paratroopers the 902d took a formidable beating-very severe casualties were reported by the enemy division commander. A tank destroyer platoon from the 705th used ground flares to sight and destroy three of the panzers reinforcing the infantry assault waves. When the 501st went into position on the 19th, its southern flank had been none too solidly anchored by the thin counter-reconnaissance screen operated by Task Force O'Hara and the tired, understrength 35th Engineer Combat Battalion (Lt. Col. Paul H. Symbol). Enemy pressure around Wardin, although subsequently relaxed, indicated that here was a gap which had better be sealed. On the morning of the 20th McAuliffe sent the 2d Battalion of the 327th Glider Infantry from the division assembly [456] area through Bastogne to relieve Company A of the engineers.6 The engineers had just climbed out of their foxhole line west of Marvie and turned the position over to the 2d Battalion when one of O'Hara's outposts saw a German column streaming into Marvie. This was the advance guard of the 901st Regiment which had finally extricated itself from the Wiltz valley. With only a single rifle company and four tanks, the Germans never had a chance. In an hour's time O'Hara's mediums had accounted for the panzers and the 2d Battalion had beaten the attackers back in disorder and occupied Marvie. The paratroopers waited through the day for the main attack to come, but the only evidences of the enemy were a smoke screen drifting in from the east and occasional tanks in the distance. Unknown to the Americans a shift in the Panzer Lehr's stance before Bastogne was taking place. The inchoate American defense forming at Bastogne was conditioned by a set of optimistic premises. The first of these was the promised arrival of the 4th Armored Division from Patton's Third Army in the south. During the night of December the VIII Corps commander, acting on word from Patton, told McAuliffe that one combat command from the 4th Armored was on its way to Bastogne and would be attached to the 101st. At noon McAuliffe and Roberts (who had been promised this initial 4th Armored force) learned that the entire division was to be added to the Bastogne defense. The certainty of the 4th Armored's appearance explains in part the routine and rather cavalier treatment accorded Capt. Bert Ezell and his little team from CCB, 4th Armored, when it arrived in Bastogne shortly after noon.7 Quite obviously McAuliffe and Middleton anticipated the early appearance of the entire armored division. A second premise-accepted in most of the 101st planning efforts on 20 December-was that the VIII Corps still had viable forces in and around Bastogne which could be employed in common with the airborne divisions. This idea, of course, went hand in hand with the very real ignorance of enemy forces and locations which obtained both in Bastogne and at Middleton's new headquarters in Neufchâteau. Earlier McAuliffe and his staff had counted on Roberts' 10th Armored combat command to reinforce a counterattack east by the 101st-a vain expectation, as it turned out. There remained the 28th Infantry Division-or at least some part thereof. In midafternoon McAuliffe sent a liaison officer to General Cota, whose headquarters was now at Sibret southwest of Bastogne, with instructions to find out the German dispositions and to ask the question: "Could the 28th attack towards Wiltz in conjunction with the 101st Airborne tomorrow?" Cota's reply is not even recorded in the 101st Airborne log. After all he could give only one answer: the 28th Infantry Division no longer existed as a division (although two of its regiments would continue in stubborn battle [457] under other commands). The fall of Wiltz on the night of 19 December had written finis to the story of the 110th Infantry, Cota's single remaining regiment. On the morning of the 20th Cota had gone into Bastogne, finding its streets jammed with vehicles, corps artillery trying to bull a way through, and a host of stragglers, including many of the survivors of the 110th Infantry. General Middleton gave Cota permission to get his people out of Bastogne and the latter ordered them out on foot, abandoning to the traffic jam those vehicles still in their possession. (So impressed was General Cota by the traffic choking the streets and alleys of Bastogne, that he advised the VIII Corps commander to keep all contingents of the 4th Armored Division out of the town.) Despite McAuliffe's failure to secure the immediate assistance which would make a full-bodied counterattack feasible, it seemed that the tactical problem facing the 101st on the evening of 20 December remained linear, that is, the creation of a homogeneous and defensible line barring entrance to Bastogne from the north and east. The corps letter of instructions reaching McAuliffe at noon on the 20th was rather more sweeping in its definition of mission. "There will be no withdrawal"this was clear enough to all concerned. "The [101st Airborne] Division will stabilize their front lines on the front P798945 [that is, Recht] to St. Vith, south along a general line east of [Highway] N15 . . . to connect with the 4th Infantry Division at Breitweiler." It may be assumed that neither Middleton nor McAuliffe took this part of the order either literally or seriously. There had been a few indications, and rumors, of enemy activity west of Bastogne-indeed the 101st had lost some of its trains in the division assembly area during the previous night-but thus far all this could be charged to raiding parties roaming on the loose under cover of night in a fluid and changing battle. In early evening a report reached Bastogne that the road northwest to La Roche and Ortheuville (where two platoons of the 705th Tank Destroyer Battalion now attached to the 101st were operating) was free of the enemy. The roads south to Neufchâteau and Arlon were still open-and waiting for traverse by the 4th Armored. So the situation looked in McAuliffe's Bastogne headquarters at 1900 on 20 December. Across the lines the German commander, Luettwitz, was none too pleased by the rather dilatory operations of his corps. He knew by this time that the American front east of Bastogne had stiffened and that his troops had been able to find no holes. On the other hand the strength of his corps was increasing by the hour as the two divisions hauled their tails up on the muddy roads-it looked as though he had the forces needed for maneuver. As a last flick of the hand Luettwitz ordered Bayerlein to throw the 902d into the night attack against Neffe. This was at most a diversion, for Luettwitz had decided to envelope Bastogne from the south and west. He intended to use the bulk of the Panzer Lehr, leaving only one of its grenadier regiments to flesh out the eastern front with the foot elements of Kokott's 26th Volks Grenadier Division, but in addition he had in hand the 39th Volks Grenadier Regiment of the 26th which had just come up behind the corps' [458] south flank. All told there was a sizable motorized force for this venture: the reinforced reconnaissance battalion, the engineer battalion, and the 902d (as soon as it could be disengaged) from the Panzer Lehr; plus the reconnaissance battalion and 39th from the 26th Volks Grenadier Division. The immediate objectives seem to have been clearly stated. The Panzer Lehr spearheads were to advance via Hompré and Sibret to St. Hubert, while the units of the 26th would start the attack from an assembly point at Remonfosse on the Bastogne-Arlon road with the intention of stabbing into Bastogne from the southwest. In fact this night operation developed into a mad scramble in which the troops from the two divisions jockeyed for the lead as if they were in a flat race for high stakes. Truly the stakes were high. Throughout this maneuver Luettwitz and his superior, General Manteuffel, had an eye single to shaking the armored columns of the XLVII Panzer Corps free for the dash to the Meuse bridges. Bastogne, sitting in the center of the web of hard-surfaced roads, was important-but only as a means to a geographically distant end. Bastogne had failed to fall like an overripe plum when the bough was shaken, but it could be clipped off the branch-or so the German High Command still reasoned-and without using Bayerlein's armor. The enemy drive across the south face of Bastogne and on to the west during the night of 20 December did not immediately jolt McAuliffe's command; it was rather a disparate series of clashes with scattered and unsuspecting units of the VIII Corps. Central to the story at this point is the fact that by daylight on the 21st the German infantry following the armored troops were ensconced on both the main roads running from Bastogne south, while light forces were running up and down the western reaches of the Bastogne-St. Hubert highway. In the north the circle had been clamped shut during the night when the 2d Panzer seized Ortheuville on the Marche road. Some of the Bastogne defenders recall in the saga of the 101st Airborne Division that their lone fight began on 20 December. "It was on this day, 20 December," reads the war diary of the 327th Glider Infantry, "that all roads were cut by the enemy . . . and we were completely surrounded." This is only hindsight. The picture of complete encirclement was built up in McAuliffe's headquarters only slowly on the 21st, nor did the ring at first seem to be hermetic and contracting. Doubtless the word passed among the regiments very rapidly-the 501st journal notes at 1030 that the last road is cut-but it was late afternoon before an armored patrol sent out by CCB affirmed that the way south certainly was closed. What were the means available for defense of the Bastogne perimeter? The 101st Airborne was an elite, veteran outfit at nearly full strength, and well acquainted with isolation as a combat formation. Only five battalions from McAuliffe's four regiments had been seriously engaged in the fight thus far. Its four artillery battalions were reinforced by the 969th and 755th Field Artillery Battalions, armed with 155-mm. howitzers whose range was nearly [459] three times that of the airborne artillery, a very important make-weight for the 101st. In addition the 10th Armored Troops were supported by the 420th Armored Field Artillery Battalion, whose mobility and tactics made it especially useful in a perimeter situation. Also available were stray gun sections and pieces from artillery units which had been decimated during the VIII Corps' withdrawal. Probably CCB, 10th Armored, and CCR, 9th Armored, had between them some forty operable medium tanks by the 21st.8 To this number of fighting vehicles should be added the light tanks, cavalry assault guns, and antiaircraft artillery automatic weapons carriers-probably no more than two platoons in each category. A very heartening addition to the Bastogne force, of course, was provided by the 705th Tank Destroyer Battalion. The highway nodal position which made Bastogne so necessary to the Germans also set up a magnetic field for the heterogeneous stragglers, broken infantry, and dismounted tankers heading west. Realizing this fact, Colonel Robert's got permission to gather all stragglers into his command. Roberts' force came to be known as Team SNAFU 9 and served mainly as a reservoir from which regular units drew replacements or from which commanders organized task forces for special assignments. It is impossible to reckon accurately the number and the fighting worth of those stragglers who reached Bastogne and stayed there. CCR contributed about two hundred riflemen; CCB may have had an equal number; General Cota culled two or three hundred men from Team SNAFU to return to his 28th Division; and one may guess there were another two or three hundred stragglers whose identity has been lost. Many of these men, given a hot meal and forty-eight hours' rest, could be used and were used, but they appear as anonymous figures in the combat record (thus: "100 infantry left for Team Browne"). McAuliffe now had the advantage of a clearly defined command structure. Before the 20th he and Colonel Roberts had commanded independently, but on that date Middleton gave McAuliffe the "say" (as General Cota had advised after his visit) over all the troops in the Bastogne sector.10 The presence of Roberts would prove particularly valuable. Early in the war he had been the armored instructor at the Army Command and General Staff School, where his humorously illustrated "Do's" and "Don'ts" of tank warfare showed a keen appreciation of the problems posed by armor and infantry cooperation. The paratroopers were in particular need of this advice for they seldom worked with armor, knew little of its capability, and even less of its limitations, and-as befitted troops who jumped into thin air-were a little contemptuous of men who fought behind plate steel. (During the Bastogne battle Roberts developed a formal memorandum on the proper employment of armor, but this was not [460] distributed to the 101st until 28 December.) On the other hand the tankers had much to learn from commanders and troops who were used to fighting "surrounded." McAuliffe's logistic means were less substantial than the tactical. The airborne division normally carried less supply than conventional divisions and the 101st had been hurried into Belgium with ammunition and grenade pouches not quite full, much individual equipment missing (overshoes, helmets, sleeping bags, and the like), and only a few truckloads of 105-mm. howitzer shells. In fact some of the first paratroopers into line had to be supplied with ammunition from the CCB trains. Fortunately Roberts' trains were full, and in some major supply items even had overages, when they arrived at Bastogne. The ability of the 101st to sustain itself had been severely diminished on the night of 19 December when German raiding parties (some reported in civilian garb) surprised and overran the division service area around Mande-St. Etienne. Most of the quartermaster and ordnance troops made their way to the VIII Corps, but the raiders captured or killed most of the division medical company. Only eight officers and forty-four men escaped. This loss of doctors, aid men, and medical supplies was one of the most severe blows dealt the 101st. A number of transport vehicles also were lost in this affray, but about a hundred trucks had been sent to the rear for resupply and so escaped. Very few of these got back to the 101st before the ring closed. In addition, Roberts had sent the CCB trucks back for resupply just before the roads were closed. There was, of course, a considerable quantity of ammunition, food, and other supplies inside Bastogne which the VIII Corps had been unable to evacuate. (Officers of Middleton's staff bitterly regretted the loss of the wine and liquors which had been carefully husbanded for consumption at Christmas and New Year). Bastogne was sizable enough to have some reserve civilian stocks, and the melange of armor, engineers, and artillery units around the city had-supplies and ammunition in their own vehicles. (Pancakes would appear regularly in the rations served during the siege, these concocted from the doughnut flour left in a huge American Red Cross dump.) Through assiduous scrounging, requisitioning, and an enforced pooling of unit resources, the G-4 of the 101st would be able to work minor logistic miracles-but these alone would not have insured the survival of the Bastogne garrison. The airborne division had been supplied by air during the Holland operation, and when, on the 21st, McAuliffe knew that his command was isolated he asked for aerial resupply. Unfortunately no plans had been worked out in advance for airlift support and the supply records of the Holland campaign-which would have made logistic calculation and procedure easier-were back in France. In the first instance, therefore, the troops in Bastogne would have to take what they got whenever they could get it. Communications would present no major problem. A corps radio-link vehicle arrived in Bastogne just before the road to Neufchâteau was severed; so Middleton and McAuliffe had two-way phone and teletype at their disposal throughout the siege. Inside Bastogne [461] there were enough armored and artillery units-comparatively rich in signal equipment-to flesh out a speedy and fairly reliable command and artillery net. Tactical communication beyond the Bastogne perimeter, however, as for example with the 4th Armored, had to be couched in ambiguous-sometimes quite meaningless-terms. Mobile forces racing cross-country, shooting up isolated posts and convoys, do not necessarily make a battle. The German dash around Bastogne was preeminently designed to encircle, not constrict. The German commanders, well aware of the fragmentization of their enveloping forces, did not consider that Bastogne had been surrounded until the evening of the 21st. The major enemy impact on this date, therefore, came as in previous days against the east face of Bastogne. The American perimeter, then taking form, represents basically a reaction to the original German intentions with only slight concessions to the appearance of the enemy in the south and west. The 502d held the northern sector of the American line in the Longchamps and Sonne-Fontaine area. Northeast of Bastogne the 506th was deployed with one foot in Foy and the other next to the Bourcy-Bastogne rail line. To the right of this regiment the 501st faced east-one flank at the rail line and the other south of Neffe. The 2d Battalion, 327th, held the Marvie position with an open flank abutting on the Bastogne-Arlon highway. The American deployment on through the south and west quadrants could not yet be called a line. In the early afternoon McAuliffe took the 1st Battalion of the 327th (then attached to the 501st) and sent it due south of Bastogne; here tenuous contact was established with the division engineer battalion-the 326th-strung thinly across the Neufchâteau road and on to the west. (The airborne engineers were not well equipped with demolition matériel and this road had to be blocked; McAuliffe phoned the VIII Corps for assistance and in the early dark a detachment from the 35th Engineer Combat Battalion came north and did the job.) Directly west of Bastogne lay the remnants of the division trains and service companies. Defense here would devolve initially on the 420th Armored Field Artillery Battalion (Lt. Col. Barry D. Browne), which was gathering infantry and tank destroyers and finally would be known as Task Force Browne. The last link in the perimeter was the 3d Battalion of the 327th, holding on a front northwest of Bastogne which extended from the Marche-Bastogne highway to Champs. The dispositions just described represent the more or less static formations in the Bastogne force, the beef for sustained holding operations. Equally important were the mobile, counter-punching elements provided by the armor, assault guns, and tank destroyers. These units, with constantly changing task force names and composition, would have a ubiquitous, fluid, and highly important role in maintaining the Bastogne perimeter against the German concentric attack. Their tactical agility on the interior line would be greatly enhanced by the big freeze which set in on the 21st. All through the night of 20 December the troops of the 506th in Foy had been [462] buffeted by German artillery. At dawn the enemy advanced on the village, and the Americans, as they had done earlier, retired to the better ground south of Foy and Recogne. This early effort was not followed up because the 2d Panzer was on its way west and had no further concern in this sector save to neutralize a possible American foray against its rear. The primary attack of the day came along the Bourcy-Bastogne rail line, right at the seam between the 506th and 501st. During the previous night Kokott had built up the concentration of his 26th Volks Grenadier Division in the woods east of the railroad to include much of the rifle strength of the 77th and 78th Regiments. The two American regiments had failed to make a firm commitment as to tactical responsibility and, indeed, the left flank of the 501st was nearly a thousand yards to the rear of the 506th. At 0830 a 506th patrol chanced upon some Germans in the woods behind the regiment's right flank. Companies D and F attacked promptly to seal the gap at the rail line while the 501st turned its weapons to deny any movement on its side. Enough of the enemy had infiltrated for McAuliffe to ask Colonel Sink to send in his 1st Battalion, which had been badly hurt at Noville, as a cauterizing force. It took three hours of musketry and, at several points, bayonet work to liquidate the Germans in the pocket; the battalion killed about so, took prisoner 85, and drove a large number into the hands of the 501st. This hot sector of the front cooled off during the afternoon. The 26th Volks Grenadier Division was realigning and extending to take over the ground vacated by Panzer Lehr, and Kokott could not afford two regiments in attack at the rail line. Through most of 21 December the Germans lashed out at the 501st with artillery and sporadic infantry assaults. On the American left flank Kokott's 77th carried the ball but the main effort was made by the 902d, attacking from an assembly area at Neffe against the 3d Battalion. The records of this battalion were lost in later fighting, but participants in the action speak of a "determined" attack by two German rifle battalions and "vicious close-in fighting." Although Colonel Ewell expected a second all-out assault when daylight ended, this never came. The 902d had its orders to catch up with the Panzer Lehr van in the west and during the night assembled for the march to rejoin General Bayerlein. South of the 501st positions the enemy seemed content to sit back and shell the headquarters of the 2d Battalion, 327th, at Marvie. The 2d Battalion records no other action than the appearance of some tanks and infantry along the Arlon road forcing a flank extension across the road. German evidence, however, speaks of attacks by the 901st in this sector which "miscarried." 11 If discretion in this particular instance proved the better part of valor, it probably was induced by the CCB tanks which had taken position on the Arlon road. Farther west the enemy was more aggressive. Having played havoc with the [463] VIII Corps' artillery and trains assembled outside Sibret, Kampfgruppe Kunkel turned north in the late morning toward Senonchamps, a village of some importance since it controlled the secondary road leading onto the Marche-Bastogne highway. The immediate prize before Kunkel, but probably unknown to him, was the American artillery groupment consisting of the 755th and 969th Field Artillery Battalions, emplaced with their 155-mm. howitzers near Villeroux, a crossroads some 2,500 yards south of Senonchamps. At Senonchamps the 420th Armored Field Artillery Battalion under Colonel Browne was busily engaged in firing against the enemy east and north of Bastogne, but Browne had been able to take some steps to secure his gun positions with a scratch force of infantry and light tanks raised by CCB. Around Villeroux, however, all was confusion and no single officer seemed to be responsible for defense of this sector. As Kunkel sped north from Sibret toward Villeroux he met the 771st Field Artillery Battalion, which abandoned its guns and fled. About this time Team Pyle (a detachment formed from the remnants of CCR and numbering fourteen tanks and a couple of hundred stray riflemen) came south on the Neufchâteau road. Kunkel hit the point of this force east of Villeroux and drove the Americans back in the direction of Senonchamps. The brief respite given the Villeroux defenders by this encounter enabled the two medium howitzer battalions to "march order" their batteries and head for Senonchamps. German infantry in half-tracks closed on Villeroux before the last howitzers could displace, but visibility by this time had dwindled to a couple of hundred yards and Battery A of the 755th alongside the headquarters battery of the 969th laid down a hail of machine gun fire which momentarily halted the enemy. This small rear guard force itself was saved by the appearance of two American tanks that casually wandered into the fight and out again. Only one howitzer was lost during the displacement to Senonchamps, and it was disabled by a mortar shell. At the edge of Senonchamps Team Pyle made a stand, for the German drive threatened to strike the 420th Armored Field Artillery Battalion (Team Browne) and the two battalions of 155'S from the rear. When the enemy infantry formed to join their tanks in an assault on the village they came directly under the eyes of Battery B of the 796th Antiaircraft Artillery Battalion, whose .50-caliber "meat choppers" quickly ended this threat. Kunkel decided to delay an attempt for conclusion until the morrow. North and northwest of Bastogne the day passed quietly, although small German detachments did make a few sorties on the Marche road. The company of the 3d Battalion, 327th, which had been sent on a lone mission to aid the survivors of the division medical company, was attacked and momentarily cut off but succeeded in rejoining the battalion. The Enemy Begins a Concentric Attack The evening situation report that reached OB WEST on the 21st made good reading. Rundstedt was convinced that the time was ripe for a concentric attack to crush Bastogne and make this road center available for the build-up required [464] to support the Fifth Panzer Army at or over the Meuse. His order to Manteuffel made the seizure of Bastogne a must, but at the same time stressed the paramount necessity of retaining momentum in the drive west. Manteuffel had anticipated the OB WEST command and during the evening visited the XLVII Panzer Corps' command post to make certain that Luettwitz would start the squeeze on Bastogne the next day-but without involving the mobile armored columns of the Panzer Lehr. Manteuffel, Luettwitz, and Kokott, who was now made directly responsible for the conduct of the Bastogne operation, were optimistic. For one thing the fight could be made without looking over the shoulder toward the south (where the Luftwaffe had reported heavy American traffic moving from Metz through Luxembourg City), because the right wing of the Seventh Army finally had shouldered its way west and seemed ready to take over the prearranged blocking line facing Neufchâteau, Arlon, and the American reinforcements predicted from Patton's Third Army. The advance guard of the 5th Parachute Division already had crossed the Arlon road north of Martelange. General Brandenberger, the Seventh Army commander, himself came to Luettwitz' command post during the evening to promise that all three regiments of the division would take their allotted positions. Kokott apparently was promised reinforcement for the attack à outrance on Bastogne but he had to begin the battle with those troops on the spot: his own 26th Volks Grenadier Division, the 901st Kampfgruppe (which had been detached from Panzer Lehr), an extra fifteen Panther tanks, and some artillery battalions. What the 5th Parachute Division could put into the pot depended, of course, on the Americans to the south. It would take some time to relieve those troops pulling out and redress the alignment of the 26th Volks Grenadier Division's battalions. There was little point to attacking the 101st Airborne in the eastern sector where its strength had been demonstrated, but west of Bastogne the Panzer Lehr and Kokott's own reconnaissance troops had encountered only weak and disorganized opposition. The first blow of the new series designed to bore into Bastogne would be delivered here in the western sector, accompanied by systematic shelling to bring that town down around the defender's ears. The battle on the 22d, therefore, largely centered along an arc rather roughly delimited by Villeroux and the Neufchâteau highway at one end and Mande-St. Etienne, just north of the Marche highway, at the other. One cannot speak of battle lines in this sector: the two antagonists were mixed higgledy-piggledy and for much of the time with no certain knowledge of who was in what village or at what crossroads. It is indicative of the confusion prevailing that the 501st tried to evacuate its regimental baggage train-which had suffered from enemy shelling-through Sibret after Kampfgruppe Kunkel had cut the road north of the town by the dash into Villeroux. (The 501st lost fifteen trucks and nearly all its bed rolls.) The arena in question earlier had been the 101st service area and contained in addition a good deal of the [465] VIII Corps' artillery and trains. Much of the fighting on the 22d revolved around two battalions of armored field artillery: Colonel Paton's 58th Armored Field Artillery Battalion, which had emplaced near Tillet-after the Longvilly battle-to support the 101st Airborne; and Browne's 420th, now operating as a combined arms team on a 4,000-yard perimeter in the neighborhood of Senonchamps. Tillet lay about six miles west of Senonchamps. Much of the intervening countryside was in the hands of roving patrols from Panzer Lehr, one of which had erected a strong roadblock midway between the two villages. On the night of the 21st the Germans encircled Tillet, where Paton, hard pressed, radioed the VIII Corps for help. Middleton relayed this SOS to Bastogne but Browne, himself under attack by Kunkel's 26th Volks Grenadier Division reconnaissance battalion, was forced to say that the 58th would have to get back to Senonchamps under its own power. Nevertheless, Team Yantis (one medium tank, two light tanks, and a couple of rifle squads) moved forward to the German roadblock, expecting to give the 58th a hand when day broke.12 Paton and his gunners never reached Team Browne, 13 which had had its hands full. Browne's force not only had to defend a section of the Bastogne perimeter and bar the Senonchamps entry, but also had to serve the eighteen 105-mm howitzers which, from battery positions east and south of Senonchamps, provided round-the-clock fire support for friendly infantry five to eight miles distant. Close-in defense was provided by a platoon of thirty stragglers who had been rounded up by an airborne officer and deployed three hundred yards south of the gun positions. (This platoon held for two days until all were killed or captured.) Browne's main weapon against the German tanks and self-propelled guns was not his howitzers but the seventeen Sherman tanks brought up by Team Pyle and Team Van Kleef the day before. These were disposed with nine tanks facing a series of wood lots west of the battery positions, four firing south, and the remaining four placed on the road to Villeroux. At daybreak the first task was to clear the enemy from the woods which lay uncomfortably near the firing batteries. Pyle's scratch force of riflemen entered the woods but found only a few Germans. Off to the northwest came the sound of firing from the area known to be occupied by a battalion of the 327th Glider Infantry; so Browne reported to Colonel Roberts that his team would join this fight as soon as the woods were clear. Before the sortie could be organized, a detachment from Kampfgruppe Kunkel struck out from Villeroux against the American flank. Direct tank fire chased the enemy away, but this was only the opener. During the afternoon the enemy made three separate assaults from the woods that earlier had been reported cleared, and again the tanks made short work of the Germans (Van Kleef reported eighteen enemy tanks destroyed during the day). As the afternoon wore on fog and snow [466]

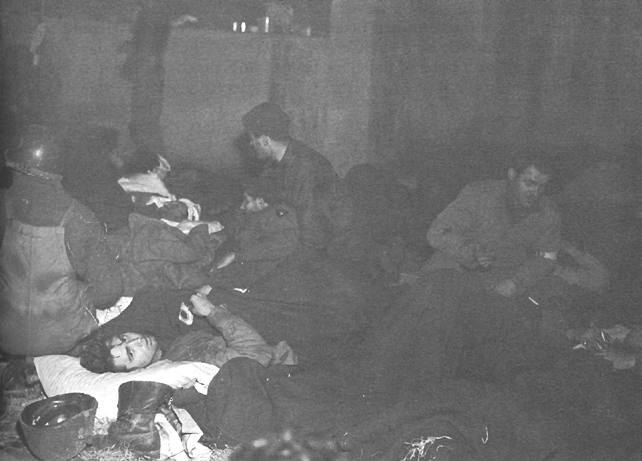

CASUALTIES IN AN IMPROVISED EMERGENCY WARD during the siege of Bastogne. clouded the scene and the tank gunners began to lose their targets. The American howitzer batteries, however, provided a static and by this time a well-defined target for enemy counterbattery fire. At twilight Colonel Browne radioed CCB that his heterogeneous team was taking "terrible casualties." Earlier he had asked for more troops, and McAuliffe had sent Company C of the 327th and Team Watts (about a hundred men, under Maj. Eugene A. Watts) from Team SNAFU. At dark the howitzer positions had a fairly substantial screen of infantry around them, although the enemy guns continued to pound away through the night. The airdrop laid on for the 22d never reached Bastogne-bad flying weather continued as in the days past. All that the Third Army air liaison staff could do was to send a message that "the 101st Airborne situation is known and appreciated." Artillery ammunition was running very low. The large number of wounded congregated inside Bastogne presented a special problem: there were too few medics, not enough surgical equipment, and blankets had to be gathered up from front-line troops to wrap the men suffering from wounds and shock. Nonetheless, morale was high. Late in the afternoon word was circulated to all the regiments that the 4th [467] Armored and the 7th Armored (so vague was information inside the perimeter) were on their way to Bastogne; to the men in the line this was heartening news. What may have been the biggest morale booster came with a reverse twist-the enemy "ultimatum." About noon four Germans under a white flag entered the lines of the 2d Battalion, 327th. The terms of the announcement they carried were simple: "the honorable surrender of the encircled town," this to be accomplished in two hours on threat of "annihilation" by the massed fires of the German artillery. The rest of the story has become legend: how General McAuliffe disdainfully answered "Nuts!"; and how Colonel Harper, commander of the 327th, hard pressed to translate the idiom, compromised on "Go to Hell!" The ultimatum had been signed rather ambiguously by "The German Commander," and none of the German generals then in the Bastogne sector seem to have been anxious to claim authorship.14 Lt. Col. Paul A Danahy, G-2 of the 101st, saw to it that the story was circulated-and appropriately embellished-in the daily periodic report: "The Commanding General's answer was, with a sarcastic air of humorous tolerance, emphatically negative." Nonetheless the 101st expected that the coming day-the 23d-would be rough. The morning of 23 December broke clear and cold. "Visibility unlimited," the air-control posts happily reported all the way from the United Kingdom to the foxholes on the Ardennes front. To most of the American soldiery this would be a red-letter day-long remembered-because of the bombers and fighter-bombers once more streaming overhead like shoals of silver minnows in the bright winter sun, their sharply etched contrails making a wake behind them in the cold air. In Bastogne, however, all eyes looked for the squat planes of the Troop Carrier Command. About 0900 a Pathfinder team dropped inside the perimeter and set up the apparatus to guide the C-47's over a drop zone between Senonchamps and Bastogne. The first of the carriers dropped its six parapacks at 1150, and in little more than four hours 241 planes had been vectored to Bastogne. Each plane carried some twelve hundred pounds, but not all reached the drop zone nor did all the parapacks fall where the Americans could recover them. Nevertheless this day's drop lessened the pinch-as the records of the 101st gratefully acknowledge. On 24 December a total of 160 planes would take part in the drop; poor flying weather on Christmas Day virtually scrubbed all cargo missions-although eleven gliders did bring in a team of four surgeons and some POL badly needed by Roberts' tanks. The biggest airlift day of the siege would come on the 26th with 289 planes flying the Bastogne run.15 The bulk of the air cargo brought to Bastogne during the siege was artillery ammunition. By the 24th the airborne batteries were down to ten rounds per tube and the work horse 420th Armored Field Artillery was expending no more than five rounds per mission, even on [468]

SUPPLY BY AIR. Pathfinder unit (above) sets up radar equipment. Medical supplies (below) are