CHAPTER XVIII The VII Corps Moves To Blunt the Salient Thus far the story of the German counteroffensive has been developed on a geographical pattern generally from east to west with particular attention given the initial battles fought by the American forces attempting to hold the shoulders of the salient, the defense of St. Vith, the VIII Corps' attempt to form a barrier line across the area of penetration, and the First Army's efforts to extend the north flank alongside the expanding bulge. While these bitter defensive battles were being waged, American forces were already moving to go over to the offensive in the south for as early as 19 December General Eisenhower and his field commanders had laid plans for a major counterattack. But before this counterattack, by the Third Army, takes stage center, three important developments are unfolding: the division of the Ardennes battlefield between Field Marshal Montgomery and General Bradley, the assembly and intervention of the VII Corps in an extension of the American north shoulder, and the initial defense of the Bastogne sector.1 Late on Tuesday evening, 19 December, Maj. Gen. Kenneth W. D. Strong, the SHAEF chief of intelligence, went to Maj. Gen. J. F. M. Whiteley, deputy chief of staff for operations at SHAEF, with a proposal which would have very audible repercussion. The German drive, said Strong, showed no sign of turning northwest toward Liège but seemed to be developing on a thrust line directly to the west. This meant, in his opinion, that the American forces north and south of the growing salient would be split by its further expansion toward the Meuse. It was his idea, therefore, that two commands should be created to replace General Bradley's 12th Army Group control of the divisive battle front, General Bradley to retain command of the troops on the southern shoulder of the salient, Field Marshal Montgomery to take those in the north under the wing of the British 21 Army Group. Strong's proposal seemed sound to Whiteley. Although both officers were British neither had broached this idea to the field marshal. Whiteley immediately took his colleague in to see the SHAEF chief of staff, Lt. Gen. Walter Bedell Smith. General Smith, famous in the headquarters for his hair-trigger temper, first reacted negatively and with considerable heat, then cooled off and admitted the logic of the proposal. Sometime that same evening Smith telephoned Bradley. Bradley was none too sympathetic toward the idea but did concede that [423] Montgomery would be more apt to throw British reserves into the battle under such a command arrangement. The next morning Smith brought up the matter in the Supreme Commander's usual meeting with his staff. Eisenhower in his turn telephoned Bradley, who agreed to the division of command. The new Army Group Boundary line, now ordered by Eisenhower, would extend from Givet, on the Meuse, to St. Vith. (That both these locations would be Montgomery's responsibility was not clarified until nearly twenty-four hours later.) The reorganization placed the U.S. First and Ninth Armies under Montgomery's 21 Army Group. Bradley would command all forces to the south of the salient-which in effect meant Patton's Third Army-and eventually he might add Devers' 6th Army Group. The reorganization required a like shift in the Allied air forces, meaning that the US IX and XXIX Tactical Air Commands (Maj. Gen. Elwood R. Quesada and Maj. Gen. Richard E. Nugent) were put under the operational control of the British Second Tactical Air Force commanded by Air Chief Marshal Sir Arthur Coningham. Because the British had very strong forces of fighter-bombers, enough of these planes were taken from IX Tactical Air Command to give Brig. Gen. Otto P. Weyland's XIX Tactical Air Command, slated to support Patton's counterattack into the German bulge, ten fighter-bomber groups.2 The decision to pass the US First and Ninth Armies to British command must have been hard to make, since both Eisenhower and Smith were acutely conscious of the smoldering animosity toward the British in general and Montgomery in particular which existed in the headquarters of the 12th Army Group and Third Army, not to mention the chronic anti-British sentiment which might be anticipated from some circles in Washington.3 This decision involved no question of Bradley's ability as a commander-that had been abundantly proven-but rather was a recognition of the communications problem presented by the German thrust between Bradley's headquarters in Luxembourg City and Hodges' headquarters, which had been moved on the 19th from Spa to Chaudfontaine. Face-to-face discussion between Bradley and Hodges-let alone Simpson-so needful if the army group commander was to give the continuous encouragement and counsel demanded in these trying days, was already difficult. If German raiders crossed the Meuse, it might become impossible. Bradley had last visited Hodges in the early evening of the 17th by motoring directly from Paris. Further visits would involve traversing three sides of a square: west from Luxembourg across the Meuse (and perhaps as far west as Reims), north into Belgium, then east again behind the none too certain American front. Telephone and radio contact still existed; indeed, Bradley talked half a dozen times on the 18th with Hodges and General Kean, the First Army chief of staff, and at least twice on the 20th. [424]

CAR BEARING GENERAL BRADLEY FORDS A BELGIAN RIVER But this was hardly a satisfactory substitute for personal presence. The 12th Army Group had approximately fifty important wire circuits on 16 December between Luxembourg and First and Ninth Armies, these extending laterally to link the three headquarters in sequence. The mainstay and trunk line of this system was a combination open-wire and buried cable line from Aubange, near Luxembourg, via Jemelle to Namur and Liège. Jemelle was a repeater station (near Marche) and the key to the whole northern network. As it turned out the Germans subsequently cut both the wire line and cable; the signal operators, as well as a rifle platoon and a few light tanks on guard duty at Jemelle, were ordered out when the enemy was in sight of the station. Very high frequency radio stations seem to have been available throughout the battle but transmission did not carry very far and had to be relayed. These stations twice had to be moved farther west to avoid capture. Nonetheless the Signal Corps would succeed in maintaining a minimum service, except for short interruptions, by stringing wire back into France and through the various army rear areas. Whether this would have sufficed for the 12th Army Group to exercise administrative as well as tactical control of the First and Ninth Armies from Luxembourg is problematical. [425]

GENERAL COLLINS, FIELD MARSHAL MONTGOMERY, AND GENERAL RIDGWAY, after A British major presented himself at the First Army headquarters about two-thirty on the morning of the 20th. Ushered up to Hodges' bedroom he told the general and Kean that Montgomery was moving 30 British Corps (Lt. Gen. B. G. Horrocks) south into the Hasselt-Louvain-St. Trond area to back up the Meuse line if needed, that four divisions were on the way and a Fifth would follow. Further, he said, the British were taking over the responsibility for the Meuse bridges at Namur, Liège, Huy, and Givet. One of Hodges' main worries could now be shouldered by somebody else. Whether there would be a sufficient force available to halt the German drive if it reached the Meuse River south of Givet was still open to question. News of the decision to split the American forces battling in the Bulge came to the First Army later in the morning when Bradley telephoned this word. Montgomery himself arrived at Hodges' command post an hour or so after noon, commencing a series of daily visits. He promptly agreed with Hodges that the V Corps' position jamming the German northern shoulder would have to be held at any cost and concurred in the handling of the XVIII Airborne Corps as it had been deployed in the past thirty-six hours. Eisenhower's formal order [426] placing the First and Ninth Armies under Montgomery's command stressed that the flanks of the penetration must be held but added that all available reserves should be gathered to start counterattacks in force. Montgomery's problem, then, was to cover the west flank of the First Army between the XVIII Airborne Corps and the Meuse while reforming his new command for the counterattack mission. It would appear that at this juncture the field marshal was thinking in terms of a counterattack against the western tip of the salient, for he told Hodges that he wanted the most aggressive American corps commander who could be found and sufficient troops to launch an attack from the area southwest of the XVIII Airborne. As to the first item, the marshal made his wishes very clear: he wanted Maj. Gen. J. Lawton Collins ("Lightning Joe"), whose VII Corps had been carrying the left wing of the December Roer River offensive; nor would he listen to any other names. Where to find the divisions needed was more difficult. But Bradley already had ordered the 84th Infantry Division to leave the Ninth Army and come in on Ridgway's flank, the 75th Infantry Division had just arrived from the United States and would reach the battle zone in a few days, the 3d Armored Division might be available in the proximate future. This, then, was the line-up for the new VII Corps when Collins reported to Hodges in the early morning of the 21st. Collins got the promise of an addition to his putative force when Brig. David Belchem, 21 Army Group chief of operations, who was visiting headquarters, suggested that the 2d Armored Division be taken from the Ninth Army reserve. Collins, who considered the veteran 2d and 3d the best armored divisions in the US Army, accepted with enthusiasm. Later in the day Montgomery met with Hodges and Simpson, confirming the proposed transfer of the 2d Armored from Simpson's command. Along the Roer River front the Ninth Army was being stripped progressively of its reserves as the German threat in the south increased. After the 7th Armored and 30th Infantry Divisions had been rushed to the First Army on 17 December, the next to go would be the 84th Infantry Division (Brig. Gen. Alexander R. Bolling), taken out of the Geilenkirchen sector. Bolling received orders on the night of the 19th to make ready for relief by the 102d Infantry Division, and at noon the next day his leading regimental combat team, the 334th, was on the road to Belgium. At Chaudfontaine the First Army G-3 told Bolling to assemble the 84th in the Marche sector, but the First Army staff could furnish little accurate information as to the location of friendly or enemy troops in that area. Temporarily attached to the XVIII Airborne Corps, Bolling had no knowledge of the embryo attack plan for the VII Corps. He was alerted, however, to be ready to attack northeast or east on order.4 [427] Two hours before midnight on 20 December the leading troops of the 84th entered Marche. The remainder of the division was coming out of the line about the same time, ready to begin the seventy-five-mile move from Germany to Belgium. As it stood it would be some twenty-four hours before Bolling could be sure of having the entire division in hand. The 84th had been blooded on the West Wall fortifications in the Geilenkirchen sector and had spent a month in combat before the move south. Battalions had been rotated in the front lines and were less battle-weary than many of the troops thrown into the Ardennes, but losses had been heavy and the division was short 1,278 men. The area in which the 84th Division (and the VII Corps) would assemble was high and rolling. There was no well-defined system of ridges but instead a series of broad plateaus separated by deep-cut valleys. Although some sections were heavily forested, in general the countryside was given over to farm and pasture land dotted with small wood lots. Concealment was possible in the narrow stream valley and the larger forests. The sector in question was bounded on the east by the Ourthe River, a natural barrier of considerable significance. At a right angle to the Ourthe another and less difficult river line composed of the Lesse and its tributary, L'Homme, ran south of Marche, through Rochefort, and into the Meuse near Dinant. Beyond Marche a plateau suffused with the upland marshes and bogs so common to the Ardennes extended as far south as St. Hubert. Marche was the central and controlling road junction for the entire area between the middle Ourthe and the Meuse. Here crossed two extremely important paved highways; that running south from Liège to Sedan; and N4, the Luxembourg City-Namur road which ran diagonally from Bastogne northwest to Namur and the Meuse with an offshoot to Dinant. Eight miles south and west of Marche the Liège-Sedan highway passed through the town of Rochefort, at which point secondary but hard-surfaced roads broke away to the west, north, and southwest. Rochefort, by road, was approximately twenty miles from Dinant and the Meuse. Marche was some twenty-eight miles from Bastogne and about the same distance from the confluence of the Sambre and Meuse at Namur. The entire area was rich in all-weather primary and secondary roads. (Map VIII) In the small, dark hours of 21 December while the leading regimental team of the 84th Infantry Division was outposting Marche and bedding down in the town, the advance guard of the crack 2d Panzer Division bivouacked on the west bank of the Ourthe only fifteen miles away. Neither of these future antagonists had knowledge of the other. At this point in the battle, the Fifth Panzer Army had taken the lead from the Sixth, whose hell-for-leather Peiper had run his tanks into a net on the north flank. Two armored divisions from the Fifth were driving for the gap which German reconnaissance had found open between the XVIII Airborne Corps and the VIII Corps. In the north the 116th [428] Panzer Division had righted itself, after the countermarch ordered on the night of 19 December, and had pushed the attack over Samrée on the 20th. The order for the following day was to cross the Ourthe in the neighborhood of Hotton, just northeast of Marche, before the Americans could bring troops into the area, and thus open the road straight to the Meuse. The 116th Panzer had lost at least twenty-four hours by the counter-march on the 19th, for on that night its armored cars had been as far west as the Bastogne-Marche road. In the neighboring corps to the south, the 2d Panzer Division finally had taken Noville on the 20th and been ordered to head for Namur, disregarding the fight which had flared up from Bastogne. When its reconnaissance battalion seized the Ourthe bridge at Ortheuville, shortly after midnight, the road to Marche and Namur opened invitingly. Luettwitz, the XLVII Panzer Corps commander, ordered Lauchert to disengage the 2d Panzer Division north of Bastogne and speed for the Meuse. Here, then, were two armored divisions from two different corps striking out for the Meuse, one in the possession of a crossing on the Ourthe, one expecting to seize a crossing in only a few hours, but both divisions with their flanks uncovered and both uncomfortably aware of the fact. Nonetheless the two corps commanders expected to thicken their armored thrusts within twenty-four hours: Luettwitz was trying to shake the Panzer Lehr loose south of Bastogne; Krueger had been promised that the 2d SS Panzer Division was on its way to the LVIII Panzer Corps. During the 21st, however, the Fifth Panzer Army's advance would be carried only by forward patrols of the 2d Panzer Division and the 116th, the two spearhead formations separated by the Ourthe River and, in ensuing days, fighting distinctly separate battles. 5 The commander of the 84th Infantry Division set up his command post in Marche on the late afternoon of 21 December under order to assemble his division in this area. The enemy, so far as he knew, was some miles away. The only friendly troops he found in the neighborhood were those of the 51st Engineer Combat Battalion, whose command post was located in Marche. This battalion was part of the small engineer force which the VIII Corps had gathered to construct the barrier line along the Ourthe River. The engineer commander, Colonel Fraser, spread out his two companies at roadblocks and demolition sites all the way from Hotton, on the river, to a point just south of the Champlon crossroads on the Bastogne-Marche highway. This latter road-block was only three miles north of the Ortheuville bridge, which the 2d Panzer advance guard wrested from the detachment of the 158th Engineer Combat Battalion during the night of 20 December. A few German patrols probed at the roadblock before dawn but no attempt was made to break through. The German reconnaissance troops bedded down in Tenneville, and batteries of the division flak rolled into position to guard the new bridgehead. For some hours this was all. Lauchert's tanks were waiting for gasoline and literally could not move. Although the 2d Panzer had captured enough American trucks, [429]

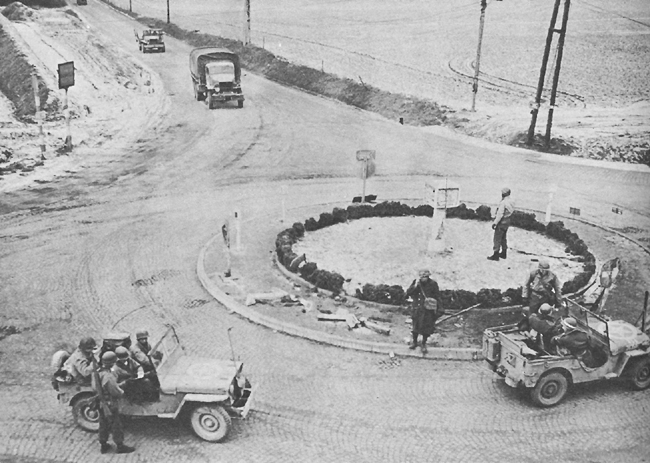

HOTTON, SHOWING KNOCKED-OUT GERMAN TANK jeeps, and half-tracks to motorize both of its bicycle battalions, the grenadiers would have to start the march west on foot for the same reason. Furthermore, fatigue had begun to tell; the 2d Panzer troops had been marching and fighting almost without respite since 16 December. Some of the human grit was beginning to slow the wheels of the military machine. But why Lauchert, a ruthless and driving commander, did not prod his reconnaissance and flak forward on the morning of the 21st can only be surmised. The first word of an attacking enemy reached the 84th Division command post in Marche at 0900, but the attack was being made at Hotton, to the northeast, where the 116th Panzer Division had thrown in an assault detachment to seize the Ourthe Bridge. General Bolling ordered his single RCT, the 334th under Lt. Col. Charles E. Hoy, to establish a perimeter defense around Marche. Meanwhile the 51st Engineer Combat Battalion asked for help in the Hotton fight. But when troops of the 334th reached the scene in midafternoon, [430] the embattled engineers, aided by a few men from the 3d Armored Division, had halted the enemy and saved the bridge-a feat of arms subsequently acknowledged by the German corps and army commanders. About noon Bolling received word from the XVIII Airborne Corps that the 334th was to hold the enemy south of the Hotton-Marche line, both these villages to be the responsibility of his division. A few minutes later a corps message arrived saying that fifteen German tanks and an infantry company had been reported five miles southeast of Marche in the hamlet of Bande and that they were heading west. By this time General Bolling had a more precise statement of his mission, for he had telephoned army headquarters about eleven o'clock to report the enemy blow at Hotton and to ask whether his single RCT should be committed to battle on the Marche-Hotton line. The answer was "Yes, hold." The question posed by the commander of the 84th had been much in the minds of Hodges and Collins that morning. With the German armored spearheads breaking out toward the west, the risk entailed in assembling the VII Corps piecemeal as far forward as Marche was very real, and the American commanders considered that perhaps the corps concentration should be made farther back to the north. But with the order given Bolling the die was cast. There remained the question of how best to bring in the rest of the 84th and the bulk of the corps. Collins asked for CCR of the 5th Armored Division, which was at Rötgen under V Corps, to be detailed to help the 3d Armored hold N4, the road from Namur. V Corps, however, still was hard beset and Hodges would not at this moment cut into its reserve. The commander of the 84th, who did not know that a 3d Armored picket still held Hotton, ordered the rest of his division to come in on a road farther to the west. By midnight of the 21st he had his entire division and the attached 771st Tank Battalion assembled and in process of deploying on a line of defense. About dark, as the second RCT detrucked, Bolling relieved the 334th of its close-in defense of Marche and moved the 2d and 3d Battalions out to form the left flank of the division, this anchored at Hotton where troops of the 3d Armored finally had been met. The 335th (Col. Hugh C. Parker) deployed to the right of the 334th with its right flank on N4 and its line circling south and east through Jamodenne and Waha. The 333d (Col. Timothy A. Pedley, Jr.), last to arrive, assembled north of Marche in the villages of Baillonville and Moressée ready to act as cover for the open right flank of the division and army-or as the division reserve. During the night the regiments pushed out a combat outpost line, digging in on the frozen ground some thousand yards forward of the main position, which extended from Hogne on Highway N4 through Marloie and along the pine-crested ridges southwest of Hampteau. The division now was in position forward of the Hotton-Marche road and that vital link appeared secure. Earlier in the day the 51st Engineer roadblocks on the Marche-Bastogne highway had held long enough to allow the 7th Armored trains to escape from La Roche and reach Marche, but at 1930 the tiny engineer detachments were [431]

84TH DIVISION MPs CHECKING VEHICLES AT TRAFFIC CIRCLE near Marche. given orders to blow their demolition charges and fall back to Marche, leaving the road to Bastogne in German hands. The main task confronting the 84th Division as day dawned on the 22d was to determine the location of the enemy. All through the day armored cars, light tanks, and infantry in jeeps and trucks probed cautiously along highways and byways east, south, and west. Some of these vehicles were shot up and the men came back on foot; others engaged in brief duels with unseen foes hidden in villages and wood lots. No German prisoners were taken, but it was clear that the enemy also was feeling his way. At noon an order from the XVIII Airborne Corps instructed Bolling to block all roads east, southeast, and south of Rochefort (seven and one-half miles from Marche) until the 3d Armored could extend its flank to this area. A rifle company was loaded into trucks and reached Rochefort in the late afternoon without trouble. Shortly after issuing this order Ridgway extended the mission of the 84th. Earlier General Collins had visited the First Army to express his concern that the enemy might crowd in south and west of Marche, thus interdicting the planned VII Corps concentration. Ridgway's order therefore called for the 84th to extend a [432] counterreconnaissance screen along the line Harsin-Grupont-Wellin, some ten miles south of Marche, at the same time sending security forces southwest to hold the vital crossroad villages at Rochefort, Wanlin, and Beauraing, the latter nearly twenty miles from the division command post at Marche. It will be recalled, as well, that Ridgway had ordered the newly arrived CCA of the 3d Armored Division to throw out a screen on the west bank of the Ourthe between La Roche and St. Hubert as further protection for the VII Corps assembly. At noon a task force from CCA was on its way but by dark had progressed only a short distance south of Marche. There it halted on word that the 335th Infantry might need help against tanks seen moving north toward Marche. Part of the task force became involved with enemy armored vehicles near Hargimont and in a short, sharp fight accounted for five of them. Bolling could free two rifle battalions and the necessary motors for what he regarded as the first-priority tasks. Early in the evening the two battalion task forces, augmented with tanks and tank destroyers, started out. The 1st Battalion of the 333d (Lt. Col. Norman D. Carnes) had orders to secure Wanlin and bar the Neufchâteau road to Dinant on the Meuse; the 3d Battalion of the 335th (Maj. Gordon A. Bahe) was to hold Rochefort and cover the road thence to Marche with detachments at Harsin, Hargimont, and Jemelle, the important repeater station. The task force from the 333d tried the Rochefort road to Wanlin but ran into the enemy near Marloie and had to detour back through Marche and roundabout through Haversin, reaching Wanlin at daybreak. The battalion of the 335th bumped into Germans at the same spot, left an infantry company to engage the enemy, then swung back through Marche and Humain, arriving at Rochefort in the early morning to find its own I Company in the town and no sign of the Germans. Although the enemy obviously was in front of the 84th Infantry Division in some strength and had shown signs of increasing his forces during the 22d, the assembly of the VII Corps was moving rapidly. Having turned over his old sector at Düren and its divisions to the XIX Corps, General Collins and some of the corps troops moved during the day into the new VII Corps area southwest of Liège. Of the divisions promised Collins the 84th was in the line, the "Hell on Wheels" 2d Armored Division closed to the rear in the area before midnight, as did the new 75th Infantry Division. The 3d Armored, of course, was still bitterly engaged as the right wing of the neighboring XVIII Airborne Corps. General Collins and his staff could feel at home in this new sector, for the VII Corps had driven the German forces out of the area during the first two weeks of September. Furthermore Collins had visited Bolling's command post and was convinced that the 84th had matters well in hand. The First Army commander's deep concern for his open western flank-a concern shared by Collins-was very considerably relieved on the 22d when Field Marshal Montgomery arrived at his headquarters with the welcome news that the British 29th Armored Brigade, equipped with fifty tanks, had taken over the defense of the Namur, Dinant, [433] and Givet bridges, and would move on the morrow to reconnoiter the west flank of the VII Corps assembly area.6 Because another twenty-four hours would be needed to deploy Collins' divisions and get the corps artillery into position, Montgomery and Hodges agreed that the VII Corps counterattack on which so much depended would commence on Sunday, the 24th. The new corps front (officially assumed by the VII Corps at 1630 on 23 December) would reach from the Ourthe River on the left to the junction of the Lesse and Meuse on the right, approximately fifty miles. The 2d Armored Division (Maj. Gen. Ernest N. Harmon) was intended to flesh out the right wing of the corps when the attack began, the 84th already held the center, and the 3d Armored Division was expected to fight its way farther south and become the left wing. Since the 75th Infantry Division was as yet untried, it was to be kept in reserve. The 2d Armored Division had small patrols scouting to the west of Marche on the 23d, but the bulk of the division assembled in three combat commands well to the north of Marche astride the main road to Huy. Its 70-mile road march (some units moved nearly a hundred miles) had been completed in twenty-two hours despite a cold rain, hazardous roads, and the delay normal to armored movement in column at night. All told the division had suffered some thirty damaged vehicles in traffic mishaps, including eight tanks. (Later one officer wryly remarked, "We lost more vehicles on the march down here than in the subsequent fighting.") The 2d Armored assembly had been handled with all possible secrecy and the entire division was under radio blackout, for Collins counted heavily on the combination of surprise and shock in the forthcoming counterattack. Events, however, were racing on to shatter the hope that the VII Corps would be allowed to mount a planned and co-ordinated assault. Harmon was conferring with his commanders an hour or so before noon on the 23d, when a message arrived that one of the armored cars out on patrol had been shot up at a little hamlet near Ciney, which was a critical road center northwest of Marche from which main highways debouched for Dinant and Namur. Without waiting for orders, Harmon dispatched CCA (Brig. Gen. John Collier) to rush full speed for Ciney and cut off any German tanks found there. This proved to be a false alarm; British armored patrols were in the town and there was no sign of the enemy. By now, however, reports of large enemy forces moving toward Ciney were pouring into the corps and division command posts. There was no longer any point in trying to hide the identity of the 2d Armored and it appeared certain that battle would have to be given without regard to the planned corps counterattack. Harmon started his whole division moving into line west of the 84th, displaced the 14th and 92d Field Artillery Battalions to support CCA, and ordered Collier to continue south on the Ciney-Rochefort road to seize Buissonville, where twenty heavy German tanks had been reported. CCA clanked through the darkness, led by a task force composed of the 2d Battalion, 66th Armored Regiment, and the [434] 2d Battalion, 41st Armored Infantry Regiment. About 2100 the combat command became involved in a scrambling skirmish with some Germans who had dismounted from half-tracks in the village of Leignon, wheeled a few small guns into position covering the road, and were now able to halt the Americans for some little time. By midnight Collier's advance guard of armored infantry was again on the move but this time with a more ambitious mission. The sortie toward Ciney had become a full-scale attack to aid the hard-pressed 84th Infantry Division and relieve those of its units cut off in Buissonville and Rochefort.7 German Armor Advances on the VII Corps When the advance guards of the 2d Panzer Division seized the bridge over the southern arm of the Ourthe at Ortheuville on the 21st, they stood only sixteen miles by road from Marche and less than forty from Dinant and the Meuse. It is difficult to determine whether the 2d Panzer Division and Manteuffel's Fifth Panzer Army were abreast of the German attack schedule or behind it. Certainly Manteuffel was two or three days behind the optimistic predictions generated in Hitler's headquarters, but on the other hand few of the lower field commands had committed themselves to any fixed march calendar. As of the 21st there is no evidence in the German accounts of any pressing concern about the rate at which the Fifth Panzer Army attack was proceeding. After all, Sepp Dietrich's much-touted Sixth Panzer Army had bogged down, the Fifth was well out in front, and German intelligence saw no viable American forces barring the door to the Meuse that had opened between Bastogne and the main valley of the Ourthe. Manteuffel still had a few problems to solve before he could make the final sprint for the Meuse River in force. Fuel deliveries for his tanks were flagging, his divisions had been fighting day and night since 16 December, a part of his left armored corps was hung up at Bastogne, and his armored corps on the right had been forced to retrace its steps with some appreciable loss in time. Manteuffel's first order, sent to the commander of the XLVII Panzer Corps, was to get the Panzer Lehr out of the Bastogne battle. With the 2d Panzer Division, now free of involvement in the army center, and with the Panzer Lehr and the 116th Panzer Divisions coming up on the left and right, respectively, Manteuffel would have the armor needed for a full-blooded blow northwest to the Meuse, and Dinant. The day of the 22d passed, however, with little activity on the part of the 2d Panzer and with little more than regrouping by Panzer Lehr, which finally had to start the march with part of the division still engaged in the fight for Bastogne. By the morning of the 23d these two divisions were on the move, but their component parts were widely spaced and [435] strung out over long miles of road. The German troops who hit the 84th Division outposts and patrols during the daylight hours and whose appearance west of Marche brought the 2d Armored Division precipitately into action constituted little more than a screen for the main body of the XLVII Panzer Corps. By the late afternoon, however, the advance guards of the 2d Panzer and Panzer Lehr had come up to the forward screen and were ready for attack. So far only the 84th Division had been identified as being in the way. The 2d Panzer Division, its first objective Marche, had the shortest road to follow but was delayed for several hours by the demolitions at the crossroads west of Champlon touched off by the detachment of the 51st Engineers. Not until early afternoon did the leading battalion of the 304th Panzer Grenadier Regiment overrun the 4th Cavalry Group outpost at Harsin, and it was dark when this battalion fought its way into Hargimont, there severing the road from Marche to Rochefort. Inexplicably the forward momentum of the 2d Panzer main column ceased early in the evening. When Luettwitz, the corps commander, hurried into Hargimont, he found that the attack had been halted for the night because American tanks were reported north of the village. Stopping briefly to tongue-lash and relieve the colonel in command, Luettwitz put in a fresh assault detachment which pushed west as far as Buissonville and there bivouacked. The appearance of this force was responsible for the reports reaching American headquarters shortly before midnight that Company E of the 333d had been trapped in Buissonville. Chief protagonist of the advance on the VII Corps thus far chronicled has been the main column of the 2d Panzer Division, which on the night of 23 December had its head at Buissonville and its body snarled in a long traffic jam on the single road through Hargimont, Harsin, and Bande. But German armored cars, tanks, and motorized infantry detachments had been encountered west and southwest of Marche all during the day. These troops belonged to the 2d Panzer reconnaissance battalion that during the night was attempting to reassemble as a homogeneous striking force west of Buissonville astride the road to Dinant. It was the point of this battalion which Collier's armored infantry encountered at Leignon. Under the new orders to attack toward Rochefort, CCA had driven a few miles south of Leignon when Capt. George E. Bonney, riding at the head of the column in a jeep, heard the sound of motors on the road ahead. Bonney whirled his jeep and rode back along the column of American halftracks, passing the word to pull off the road and let the approaching vehicles through. When the small German column was securely impounded, the Americans cut loose with the .30-caliber machine guns on the halftracks, killing thirty of the enemy and capturing a like number. Bonney had his leg almost cut off by slugs from one of his own tanks farther back in the column. Since the night was far spent, the enemy strength and location were uncertain, and his command had few if any detailed maps, Collier ordered the CCA task forces to reorganize and to laager until dawn. The leading task force by this time was near the village of Haid, eight miles from Rochefort. On the day before (23 December), [436] the Panzer Lehr had been brought forward on the left wing of the 2d Panzer Division, General Manteuffel himself leading the march from St. Hubert. The immediate objective was the road center at Rochefort, for this town, like Marche, had to be secure in German hands if a major assault with all its impedimenta was to be launched on the roads leading to Dinant. German gunners had shelled the town in the late afternoon without any return fire, and just at dark, scouts came back from Rochefort to report that the town was empty. Apparently the scouts had not entered Rochefort. If they had, they would have learned that the 84th Division had built up a garrison there during the past twenty-four hours. In fact the Rochefort defense under Major Bahe consisted of the 3d Battalion (minus Company L) of the 335th; a platoon each from the 638th Tank Destroyer Battalion, 309th Engineer Combat Battalion, and 29th Infantry; plus two platoons of the regimental antitank company. The approach to Rochefort by the St. Hubert road lay along a narrow defile between two hills. Perhaps General Bayerlein's military intuition told him that the town was defended and that the ground and the darkness presented some hazard, for he gave the order, "Also los, Augen zu, und hinein!" ("OK, let's go! Shut your eyes and go in!") The leading battalion of the 902d rushed forward, only to be hit by cross fire from the hills and stopped cold by a formidable barricade on the road. The Germans took heavy casualties. Bayerlein then set to work in systematic fashion to take Rochefort. He brought forward his guns to pound the hills and the town, and edged his troops in close as the night lengthened. He did not forget his main task, however, and sent a part of the 902d around Rochefort to find a way across L'Homme River, which looped the town on the north. These troops found one bridge intact, giving the Panzer Lehr access to the Dinant road. During the night Manteuffel and Luettwitz discussed the plan to seize Dinant. They altered the axis of the 2d Panzer attack to conform with the actual tactical situation, struck Marche from the operations map as an immediate goal, and instructed Lauchert's armor to bypass it on the southwest. Rochefort, it appeared, would have to be taken, but it was intended that the Panzer Lehr would reinforce its bridgehead force promptly and get the attack rolling toward Dinant while battering down the Rochefort defense. Luettwitz, a bold and experienced corps commander, was anxious to push on for the Meuse but worried about his flanks. Marche was an obvious sally port through which the Americans could pour onto the exposed flank of the 2d Panzer Division unless something was done to cut the road north of the town and thus interdict reinforcement. This task had been assigned the 116th Panzer Division, whose main strength was still separated from Luettwitz' divisions by the Ourthe River. Promising that the 116th would come forward to cover the 2d Panzer flank, Manteuffel set out by automobile to give the 116th a little ginger. The army group commander, Model, had said that the 9th Panzer Division would support the 2d Panzer on 24 December, but neither Manteuffel nor Luettwitz seems to have counted on its appearance. While commanding the 2d Panzer Division in Normandy Luettwitz [437] had learned the hard way about the reliability of flank protection promised by others. He had already begun to strip troops from both of his forward divisions for deployment on the shoulders of the thrust being readied for Dinant. The Panzer Lehr had most of one regiment (the 903d), as well as its antiaircraft and engineer battalions, strung all the way from Moircy (west of Bastogne) to the area southwest of Rochefort as cover on the left for the division attack corridor. Bayerlein had been forced to leave one regiment in the Bastogne battle; so his effective assault force on the 24th consisted of the division reconnaissance battalion, some corps and division artillery, and one reinforced regiment. All of the 2d Panzer Division was available to Lauchert, but the kampfgruppen of the division were widely separated and for every mile forward troops would have to be dropped off to cover the division north flank. When daylight came on the 24th, the head of the leading kampfgruppe had advanced well to the northwest of the Marche-Rochefort road in considerable strength. In this kampfgruppe were the reconnaissance battalion, one battalion of Panthers from the 3d Panzer Regiment, the 304th Panzer Grenadier Regiment, two artillery regiments, a battalion of heavy guns, and two-thirds of the division flak, the whole extending for miles. The remainder of the 2d Panzer remained on the Harsin road southeast of Marche under orders from Luettwitz to protect the corps right shoulder. The Main Battle Is Joined Pitched battles and fumbling skirmishes flared up all along the VII Corps front on 24 December. But the VII Corps front was not a homogeneous line, and the German drive was not conducted by division columns whose units were contiguous to each other and flanked by overwatching screening forces on parallel roads. The opposing commanders by this time did have a fairly accurate idea of what formations were on "the enemy side of the hill," but neither Americans nor Germans were too certain as to where these formations would be encountered. The hottest points of combat on the 24th were Rochefort, Buissonville, and the Bourdon sector east of the Hotton-Marche road. At Rochefort the Panzer Lehr commander began his main attack a couple of hours after midnight, but the defenders held and made a battle of it in houses and behind garden walls. Companies I and K of the 333d concentrated in and around a large hotel, dug in a brace of 57-mm. antitank guns and a section of heavy machine guns in front of the hotel, and so interdicted the town square. About 0900 on the 24th the 3d Battalion lost radio contact with the division, but four hours later one message did reach Marche: an order from General Bolling to withdraw. By this time a tree burst from a German 88 had put the antitank guns out of action. To disengage from this house-to-house combat would not be easy. Fortunately the attackers had their eyes fixed on the market place in the center of the town, apparently with the object of seizing the crossways there so that armored vehicles could move through from one edge of the town to the other. So preoccupied, they neglected to bar all the exits from Rochefort. Driven back into a small area [438]

CAPTURED GERMAN 88-MM. GUN around the battalion command post where bullet and mortar fire made the streets "a living inferno," the surrounded garrison made ready for a break. Enough vehicles had escaped damage to mount the battalion headquarters and Company M. The rest of the force formed for march on foot. At 1800 the two groups made a concerted dash from the town, firing wildly as they went and hurling smoke grenades, which masked them, momentarily, from a German tank lurking nearby. Sgt. J. W. Waldron manned a machine gun as a line rear guard, was wounded, but rejoined his company. (He received the DSC.) The vehicular column headed west for Givet, and it is indicative of the widely dispersed and fragmented nature of the German forces on this day that the American column reached the Meuse without being ambushed. The foot column, led by Lt. Leonard R. Carpenter, started north with the idea of reaching the outposts of the 3d Armored task force known to be thereabouts, but here the spoor of the enemy was very strong and movement was slow. During the night some trucks were sent east from Givet and found parts of Companies I and K; two officers and thirty-three men belonging to Company I were picked up in an exhausted state by 2d Armored patrols and brought back to the American lines. The defense of Rochefort had not been too costly: fifteen wounded men, under the care of a volunteer medic, [439] were left in the town and another twenty-five had been killed or captured. But the Panzer Lehr commander, who had fought in both engagements, would later rate the American defense in Rochefort as comparable in courage and in significance to that at Bastogne. Significantly, the Panzer Lehr Reconnaissance Battalion carried the attack for the Meuse without any help from the rest of the division until after midnight, when the 902d finally reached the Buissonville area. Buissonville had been the primary objective of the 2d Armored Division when Harmon first propelled his CCA into action. True, Rochefort was the goal when CCA resumed its march on the morning of the 24th, but Buissonville first had to be brought under American control. A glance at the map will show the reason why. The village lay in a valley where the Dinant-Rochefort highway dipped down, but in addition it controlled the entry to that highway of a secondary road net running west from the Marche-Rochefort road. The hamlet of Humain, four miles to the east, was the nodal point of this secondary system. During the night the Humain-Buissonville road had been jammed with German columns from the 2d Panzer reconnaissance battalion and advance guard. But now the wealth of good, hard-surfaced roads which characterize this part of Belgium came into play. Entering the main highway at Buissonville, the German units had gone north for about a mile, then made a V-turn back onto a secondary road running straight west to Conjoux, a village four miles south of Ciney. The Belgian telephone operator at Conjoux attempted to get word of this movement to the Americans, but the message had to pass surreptitiously through a number of hands and did not reach the 2d Armored command post until the afternoon of the 24th. The CCA sortie from Ciney, as a result, was being made obliquely to the German axis of advance and would intersect the enemy line of march at Buissonville only after the leading kampfgruppe of the 2d Panzer had passed on to the west. This is not to say that Collier's task forces encountered no opposition when CCA resumed the attack on the morning of the 24th. Flank guard and blocking detachments backed by tanks had been left to screen the 2d Panzer line of communications on the north and these had to be disposed of. Furthermore, CCA had to proceed with some caution, feeling out to the flanks as it went; indeed General Harmon added a reconnaissance company to Collier's command because "the situation is changing all the time." The leading American task force reached Buissonville in early afternoon and formed for an assault to encircle the village from the north. By chance the second task force, advancing in echelon on the right flank, had run into antitank fire and, in process of maneuvering onto a ridge overlooking the German guns, saw its sister detachment moving into the attack. An enemy column, coming in from Havrenne, appeared about the same time on the opposite side of the village. While the American attack swept through and round Buissonville, the tank and tank destroyer crews on the ridge opened fire, laying their guns at four thousand yards, and directing the salvos crashing in from the field batteries [440] supporting CCA. The final tally was 38 wheeled vehicles, 4 antitank guns, 6 pieces of medium artillery, 108 prisoners, and a large but uncounted number of German dead. After this action a squadron of P-38's strafed the village, probably on a mission which had been called for before the assault, killing one American officer and wounding another before the airplanes could be diverted. With Buissonville in hand, Harmon ordered Col. John MacDonald, whose 4th Cavalry Group had just been attached to the 2d Armored, to take Humain and thus put a stopper in the narrow channel between his division and the 84th which led to the west and the rear of the Marche position. MacDonald had only the 24th Squadron-his 4th Squadron was deploying in the west as a screen between CCA and CCB-and in the early evening he sent Troop A into Humain. The troopers experienced little opposition. Mines and booby traps were their greatest hazard, and by midnight they had full control of the village. All through the day messages had come into the 2d Armored Division headquarters telling of German tanks in increasing numbers in and around Celles, a main crossroads village southwest of Ciney and only four miles from the Meuse River. During the morning the British light armored cavalry patrolling this area had been forced back toward Dinant. At midday two P-51's flew over to take a look at Celles but got an exceedingly warm reception from flak batteries there and were driven off. Further evidence of a large German concentration came in the afternoon when the Belgian report of enemy columns in Conjoux finally reached the Americans. Harmon had not waited for confirmation of the early British reports, the right and rear of CCA being too exposed for that. At 1045 he ordered CCB (Brig. Gen. Isaac D. White) to secure Ciney-at the moment occupied by some of Collier's troops-"as a base for future operations." At the same time the division artillery commander, Colonel Hutton, sent two battalions of armored artillery into firing positions north of Ciney. (Throughout the day artillery support for both the 2d Armored and the 84th had been rendered under difficult circumstances. The location of friendly units was none too certain and a number of the advanced outpost positions along the VII Corps front were beyond the range of their own guns.) The eastern flank of the VII Corps was the third area of hot combat on the 24th. On the previous night the 116th Panzer Division finally had begun to build up a bridgehead on the west bank of the Ourthe. Perhaps Manteuffel's visit had had some effect, or, more likely, the 116th had more troops for the attack now that reinforcements were arriving to take on the Americans in the Soy-Hotton sector. The mission set for General Waldenburg's division was of critical importance to the Fifth Panzer Army attack. First, the 116th Panzer was to break through the American position forward of the Hotton-Marche road. Then, having cleaned out Marche in the process, the division was to swing north onto the Baillonville road, which offered good tank going, drive west through Pessoux, and make contact with the 2d Panzer Division in the neighborhood of Ciney. At that point the two divisions would provide reciprocal protection for their inner flanks. [441] Waldenburg was low on fuel for his tanks but attempted to set the ball rolling by sending two rifle companies through the dark to infiltrate the American lines at the junction point of the 334th and 335th Regiments. The tactic-penetration along boundary lines-was a German favorite, attended by success in the initial days of the offensive. The two companies (dismounted troops of the division reconnaissance battalion) stealthily worked their way forward and at dawn were to the rear of the 334th. There they sought cover on a wooded ridge north of Verdenne. This village, outposted by the Americans, was the immediate goal of the attack planned for the 24th. Commanding the Marche-Hampteau road-roughly the line held by the left wing of the 84th Division-it afforded immediate access via a good secondary route to Bourdon on the main Hotton-Marche highway, and its possession would offer a springboard for the German armored thrust. The 116th Panzer Division did not attack with daylight, for its fuel trucks had not yet appeared. Instead Waldenburg sent detachments of the 60th Regiment into the Bois de Chardonne, the western extrusion of a large wood lot partially held by the Germans southwest of Verdenne. Unusual movement in the Bois was noticed by the Americans during the morning, but this came into really serious light about noon when a prisoner revealed the presence of the two companies behind the 334th. General Bolling gathered the 1st Battalion, 334th, and three tank platoons of the 771st Tank Battalion to trap the infiltrators. It appears that his opponent, General Waldenburg, had postponed the German attack for an hour or so but that this order did not reach the two forward companies. When the American tanks suddenly appeared on the wooded ridge north of Verdenne, they ran head on into the enemy just assembling at the wood's edge in assault formation. The Germans broke and fled, some fifty were captured, and the woods were cleared. But this was only the first act. An hour later five enemy tanks and two half-tracks carrying or covering a hundred or so grenadiers struck Verdenne from the south, engaged the second platoon of Company I in what Waldenburg later called "a bitter house-to-house battle," finally overwhelmed the Americans, and pushed on to a château a stone's throw north of the village. In a last assault at eventide the attackers drove this wedge deeper. Companies I and K of the 334th fell back to a new line barely in front of the crucial Marche-Hotton road, and German light artillery moved up to bring the road under fire. Christmas Eve in the far western sector of the Ardennes Bulge found various shadings of uneasiness in the American headquarters and a pall of foreboding, silver-lined by the proximity of the Meuse, in the German. The attack planned for the VII Corps had turned into a defensive battle. On the east wing the 3d Armored (-CCB) was hard pressed and some of its troops were surrounded-indeed two regiments of the 75th Infantry Division were en route to help General Rose. The 84th Division, so far as then was known, had lost a battalion in Rochefort, might be driven out of Marche, and stood exposed to an armored exploitation of the penetration made at Verdenne. The 2d Armored Division had had a good day but was not yet securely linked to the 84th on the [442] left and could only surmise what tank strength the Germans had accumulated opposite CCB on the right. Field Marshal Montgomery, chipper as always but cautious, had taken steps during the day to bring the 1st Division (British) across the Meuse and into backstop position behind the First Army in the sector southeast of Liège. Other British troops were on the move to assist the 29th Armoured Brigade (British) if the enemy should hit the bridges at Givet or Namur. This was good news to the First Army commander and his staff, not to mention that some elation was abroad as the result of Allied air force activity on this clear day and the reports of prisoners and booty taken from the 1st SS Panzer Division at La Gleize. The gloomy side of the picture was all too readily apparent. The fall of St. Vith had opened the way for fresh forces and new pressure against the army center and right. The 82d Airborne Division was exposed to entrapment in the Manhay sector and in the course of the evening Hodges would order a withdrawal. The situation as it appeared in the VII Corps on the army right wing was, as just described, somewhat of a cliffhanger. On the left wing, in the V Corps sector, the enemy appeared ready to resume strong offensive operations, and after their Christmas Eve supper Hodges and Huebner sat down to plan the evacuation of the corps' heavy equipment in order to leave the roads free in the event that withdrawal to the north became mandatory. In the higher echelons of German command the attitude on Der Heilige Abend became more somber as the distance between the particular headquarters and the 2d Panzer position at the tip of the Bulge diminished. Rundstedt seems to have become reconciled, with the fatalism and aloofness of the aged and veteran soldier, to whatever the fortunes of war now might bring. Model, the commander of Army Group B, was outwardly optimistic; his order for Christmas Day called for the passage of the Meuse and the capture of Bastogne. This official mien of optimism contrasts sharply with the attitude his personal staff had noted on 18 December when, it since has been reported, he phoned Rundstedt and Jodl to say that the offensive had failed. Perhaps he saw in the events of 24 December the possibility that the Meuse at least might be reached and some degree of tactical success east of the river be attained, thus confirming his earlier opposition to the Big Solution dictated by Hitler and Jodl. Manteuffel, as Fifth Panzer Army commander, was the man in the middle. He was well aware of the exposed and precarious position of the 2d Panzer Division. He had traveled the forward roads at the tip of the salient, and his practiced eye recognized that the narrow corridor to the Meuse must be widened if the last stage of the drive to the river was to be logistically supported. Doubtless he recognized the tactical merit of Luettwitz' suggestion, probably made late in the afternoon of the 24th, that the forward columns of the XLVII Panzer Corps should be withdrawn from their position of dangerous isolation until such time as reinforcements arrived. On the other hand Manteuffel was well aware of the Fuehrer's attitude toward surrendering ground and could not possibly acquiesce in Luettwitz' proposal. During the evening Manteuffel telephoned Jodl with a personal and desperate [443] plea for assistance: he argued that his army, not the Sixth, was carrying the main effort of the offensive and that the divisions in the OKW reserve earmarked for Sepp Dietrich should be released at once to reinforce the attack to the Meuse. It would appear that Jodl spoke reassuringly of divisions en route to the Fifth Panzer Army, but this must have brought very cold comfort to Manteuffel.8

[444]

|