FORT GEORGE G. MEADE, Md. (April 17, 2012) -- Ask any military kid and they'll tell you: Having a parent in the military can be hard. They must cope with deployments of one or both parents, frequent moves, making new friends, changing schools and the fear that comes from having a parent in harm's way. Often times, kids with parents in the military are asked to do a little more than their non-military counterparts, to grow up just a little faster.

Military kids also have to deal with their peers, and occasionally adults, misunderstanding the military lifestyle or even insulting it. Sometimes, it's difficult to explain to outsiders what having a parent in the military is like.

That's why programs developed with military children in mind -- programs that encourage them to express themselves creatively, and in turn, become better communicators -- are important.

A Backpack Journalist is one such program. It was pilot tested in 2008 with 12 young people attending basic writing and journalism classes on a university campus, Linda Dennis, program manager, explained. During the pilot, program administrators discovered that while younger children expressed themselves easily, older children -- specifically middle and high-schooled aged -- were struggling.

Hosting the classes on campus became cost prohibitive, so Dennis and the other administrative members made the program mobile.

"We built a digital lab and teachers got together and decided that we would go out and offer it at events," Dennis said. The Texas National Guard Family Support Foundation funded the development of the lab. After the successful pilot test in San Antonio, the program was presented to the Office of the Secretary of Defense for Reserve Affairs. From there, it took off.

A Backpack Journalist, which works mainly with National Guard and Reserve families, has three central goals: to help children learn how to express themselves creatively, communicate honestly and build self esteem through a journalistic curriculum.

"The key (goal) that we really strive for is to help a young person build resilience through creative expression," Dennis emphasized. The program offers writing, song writing, digital storytelling, filmmaking, poetry and photography modules that help teach youth different forms of expression.

A total of 26 modules in the program are directed at creative expression, Dennis said. Additionally, there are lesson plans that target specific emotions to help foster better interpersonal communication.

In March, the program held a camp at Fort Meade, Md., on writing and filmmaking, with children from the Army Reserve's 200th Military Police Command. One of the central themes of the weekend camp focused on what it is like to be a military child.

As a surprise, and in an effort to enhance his son's homeschooling experience, Capt. Tobias Clark enrolled his 12-year-old son Evan in the Fort Meade Backpack Journalist camp.

During the camp, Evan produced a minute-long video describing his life as a military kid. After multiple family moves, he summed up his experience in one word: unpredictable.

"I've heard a lot of things said about (life as a military youth), but never the word unpredictable," Dennis said. "And the way he said it was like, 'Wait a minute, that's the one word we all need to think about,' because it is unpredictable. And he explained it, (and) he went on to explain why."

Participants from one of the program's other sessions will be presenting a music video, "PTSD Won't Stop Me," to Congress in mid-April. Evan was invited to present his video as well.

"They were impressed by his video," Evan's mom, Ashley Clark, said. "It's a once-in-a-lifetime experience and we're really proud of him."

"(Dennis' goal) is to one, bring journalism to children and increase their writing skills and (self) awareness through photography (and other) forms of media," Ashley said. "But then her heart is in (supporting) military children, (helping) them express their thoughts and ideas through different types of media, and (teaching) them to present it."

In the camps, students like Evan are introduced to artistic pursuits like writing, photography and filmmaking, among others. One of the photography exercises includes the Photography Ice-breaking Experience, or PIE.

Children are paired up with someone they've never met and asked to conduct interviews, Dennis explained. The kids pick props for their partners based on interview answers and take photographs using those props. Afterward, they use the photographs to present their new friends to the group. Exercises like PIE help the kids learn the basics of interviewing techniques and public speaking, Dennis said.

"Grammar and punctuation are the last (things we stress)," Dennis said. "The first thing we do is say, 'If you can talk, you can write.'"

The program combines different teaching methods to ensure each participant takes away something from the experience, Dennis explained. The modules are blocked in two-hour sessions and rotated, so if one child doesn't enjoy the writing session, he may be able to learn writing-related skills in the song writing or filmmaking sessions.

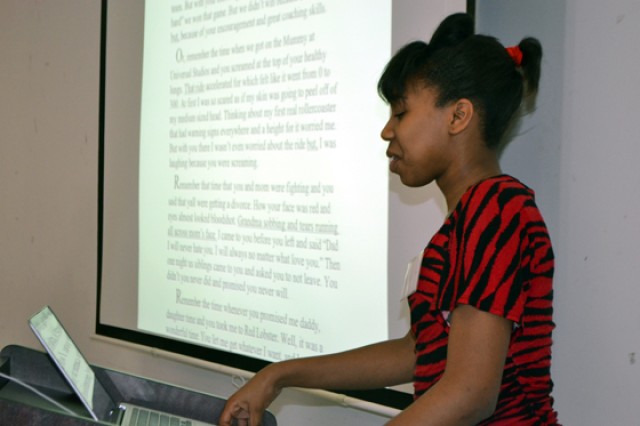

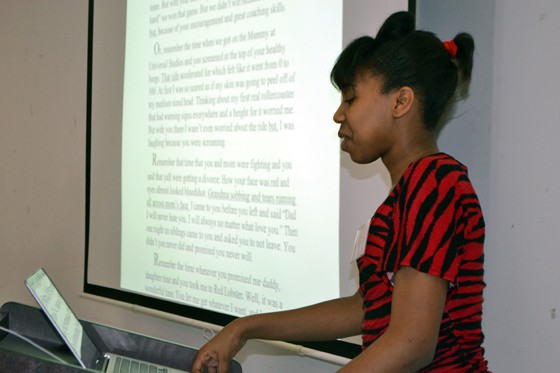

Kiara Jackson was also a participant in the writing and filmmaking workshop at Fort Meade. There, she learned how to improve her writing, but just as important, about the different perspectives of other military children.

"I learned what they had to go through," she said. "Like some of them had parents that were deployed to Afghanistan and things like that I got to learn about how they felt and I got to see other circumstances that I do not have."

The program also taught her that some children don't understand what military kids have to go through, Jackson explained. Part of the program's focus is to make the participants become better communicators so they can help explain the military lifestyle to others.

Jackson attends a public school off post. Her mother, Master Sgt. Marcia Jackson, is the inspector general with the 200th Military Police Command. Some of her classmates make fun of the military lifestyle and make rude comments when the class discusses the military, which bothers her.

"They think that it's all about (your parents being) in Afghanistan or Iraq or something like that," Jackson said. The program gave her the tools to help her express that just because a parent isn't in a war zone, doesn't mean that her position in the Army isn't worthwhile.

"It's like they gain a sense of confidence," Dennis said of students who have completed a workshop. "They discover its OK to be military kids, it's fine. They have different stresses and different challenges, but they're good kids. To express themselves is sometimes difficult, especially when they are in regular schools and are surrounded by other kids that aren't in the military, that don't understand it."

Evan found the program helpful on both academic and personal levels. He said he believes that it helps military children understand that it's all right to share their experiences, and it gives them the tools to express themselves.

"Even if you don't feel like doing it, it can really help you in the long run," he said. "If you don't feel like it may help you right off the bat, it may help you later on during a move, or when your mom or dad deploys. It's just good to do. It prepares you."

Dennis has received positive feedback from participants' parents, who said that children who didn't communicate much before are now talking more.

"Once a young person get comfortable and learns how to express themselves, whether it's music, or writing, or picking a camera up -- whatever it is that they learn how to do that's not traditional school -- you will find that they will be less troubled, less anxious," Dennis said. "There is something to finding one's voice that's very powerful within the human spirit."

For more information about A Backpack Journalist, and a schedule of the program's upcoming camps and events, visit www.abackpackjournalist.com

Social Sharing