FORT POLK, La. -- Any man's death diminishes me because I am involved in Mankind;

And therefore, never send to know for whom the bell tolls; it tolls for thee" -- John Donne, English poet, 1572-1631

And so on Sept. 11, at 9:03 a.m., the Main Post Chapel bells will toll; their haunting reverberations echoing throughout Fort Polk. The bells toll for the 2,974 people who died in the terrorist attacks of Sept. 11, 2001. They toll for the diminishment of the nation -- the world -- in the face of such tragedy. They toll for the loss of innocence, the naive belief that the nation was invulnerable to attack. They toll for every American: The bells "toll for thee."

Sept. 11, 2001: Now, eight years later, the date is etched into the nation's psyche, a date that belongs to America's collective memory. It's the date when unsuspecting civilians were

unwittingly used as terrorist pawns, a date when the best of human nature overcame its worst.

At Fort Polk the day dawned bright and clear. The ambient quality of light shining into office windows was gentle, a subtle reminder that cooler weather would soon overtake the harsh heat of summer. It was a Tuesday, the second day of the work week. People had settled into their routines. It was a day like any other.

At 8:46 a.m. eastern, American Airlines flight 11 crashed into New York City's World Trade Center North Tower and America watched in disbelief. United Airlines flight 175 hit the South Tower at 9:03 a.m. and America watched with horror. Another group of hijackers flew American Airlines flight 77 into the Pentagon at 9:37 a.m. and America watched with the undeniable realization that the nation was under attack. A fourth flight, United Airlines flight 93, whose ultimate target was later identified as the U.S. Capitol, crashed near Shanksville, Pa., at 10:03 a.m. And with those acts of terrorism, Sept. 11, 2001, became a day unlike any other.

Confusion and panic ensued. But before the dust had settled, while the fires still burned -- and in the midst of conflicting reports -- Americans responded.

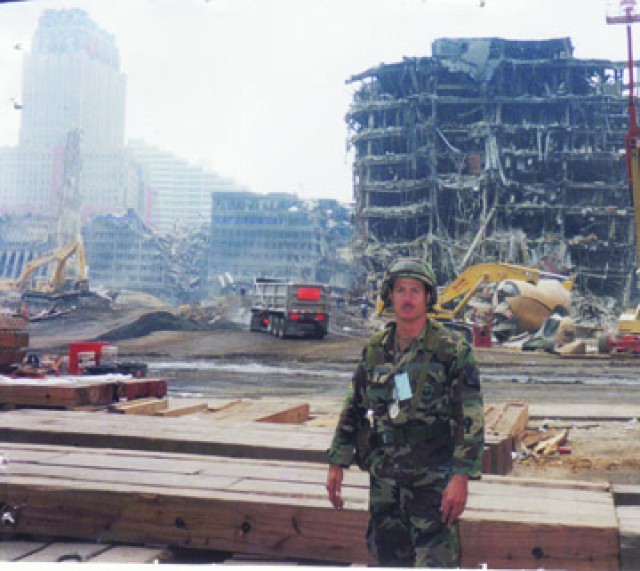

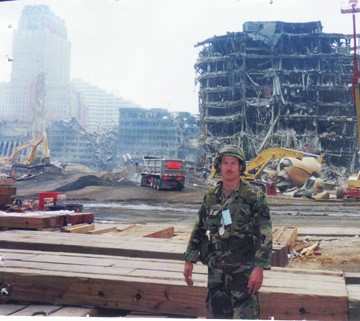

Paul Whelan is one of those Americans. Now in the Physician's Assistant Program at Bayne-Jones Army Community Hospital, during the attacks Whelan was with the New York State Police and the New York National Guard.

Like millions of other Americans, Whelan was uncomprehending when the news reports began flooding the airwaves. "I heard about a plane striking one of the World Trade Center towers, and it just didn't make sense. I thought it had to be a small commuter plane," he said.

"And then I heard that it was a full-sized commercial jet, and I felt cold chills throughout my body. A million things went through my mind, but terrorism was not among them," Whelan said. Until the second plane hit the South Tower 17 minutes later. "After that, two and two added up, and I wondered if my Guard unit would be called to respond."

It was. About two weeks after the attacks, Whelan found himself bunking at Fort Hamilton, an old Guard base in Brooklyn. "Every morning my unit was bussed to Ground Zero. I remember the first ride there. I wondered exactly what I would see. Near the site you could see closed parking garages filled with dust and debris. In those garages were abandoned cars, and you knew that many of those cars probably belonged to people who were no longer alive. It was an eerie feeling," he said.

Riding the bus, transfixed by what he saw outside the window, Whelan tried to prepare himself or that first glimpse of Ground Zero. "On T.V. you only get a small snapshot of the devastation. Seeing the debris, seeing the big picture and the massiveness of the destruction ... There were blocks of rubble, the biggest buildings in the world had been laid waste. The scope of the tragedy was vast.

"I felt angry about what had happened to America and deeply saddened for those who lost their lives and the families that were affected. Going back and forth to Ground Zero during the following weeks, there were thousands lining the perimeter with flowers and cards, crying and weeping. They were there every day. It was just tragic," Whelan said.

Whelan spent about two months at Ground Zero, helping secure the perimeter. For him, the tolling of the Main Post Chapel bells summons heart-wrenching memories. "At Ground Zero, the rescue workers who came across bodies would ring a bell so that everyone in earshot could have a moment of silence. Those bells rang countless times while I was there."

Before Sept. 11, 2001, a metal sculpture of the earth stood between the World Trade Center towers, a symbol of the international flavor of the business that took place there. Whelan struggled to find the words to describe how he felt seeing that globe after the towers collapsed.

"It was on the first or second day when I saw them pulling that globe out of the rubble. They placed it on a flatbed trailer. I felt so much emotion seeing that. I thought, 'Oh my God, this is a symbol of how the world has been smashed and crushed.' I can't tell you how I felt as I watched that globe being hauled out of there -- to the dump, I thought."

But the globe survived. It has been placed nearby at Battery Park, an eternal flame standing guard. It serves as a monument to those who died that day, and a reminder that despite great loss, the world can and will survive terrorism.

And the American spirit remained intact as well, even in the midst of despair.

"There was so much support there," Whelan said. The American Red Cross and other organizations had food, comfort items, clothing for the rescue workers and helped you contact home if needed. The nearby churches had priests on hand, military chaplains were all over the place. People came from across the country to help out however they could."

Like most Americans post 9-11, Whelan said he has changed. He has become less trusting, attuned to the fact that the impossible sometimes does happen.

"I would never have thought that terrorism to that scale would occur in the United States. I've become very wary. We all know now that it can."

While the terrorists boarded the planes they would later commandeer and crash, Col. Francis B. Burns, Fort Polk's garrison commander, was at work at the Pentagon. After spending the weekend attending the funeral of a close friend, Burns said he felt tired and emotionally drained -- until he saw news footage of both planes hitting the twin towers. "I immediately called one of my contacts who also worked at the Pentagon to ask what was happening. He told me they were tracking other planes, and he would call me back. I never got the return call."

Throughout the office, Burns and his coworkers were transfixed by the unfolding tragedy. One of those coworkers, an engineer, believed the towers would never come down. And at 9:37 a.m., Burns felt the massive Pentagon shake -- the aftershock of an explosion.

Now, eight years later, while the chapel bells toll, memories of that day linger: the disheveled secretary bursting into the office; an Army lieutenant colonel directing them away from the blast site to another exit; linking up at the office rendezvous point; the boss telling them all to go home and keep in touch via e-mail.

"I walked away from the flames still not knowing what had happened and who was left in the building," Burns said.

Burns made his way across Washington, D.C.'s Memorial Bridge toward the Metro station. But when he arrived there, the metro wasn't running. "Then I tried to rent a bicycle to ride home, but the rental owner wanted to physically hold my credit card as collateral, so I literally hit the trail."

It was a long walk -- 15 miles to Silver Spring, Md., a walk made longer by uncertainty over the wellbeing of his family. Listening to his Walkman as he made the trek, Burns heard that his coworker's prediction was wrong: The twin towers had collapsed. After hours walking, Burns arrived home to the hugs and kisses of his family.

Two days later, Burns returned to the Pentagon, the odor of the charred ruins permeating the building. That smell, and the aftermath of the terrorist attack are fresh in his mind.

"I remember visiting Brian Birdwell (who worked at the office of the Assistant Chief of Staff of Installation Management) at the George Washington Hospital Burn unit. More than 60 percent of his body was burned -- his head was the size of a melon. He was on his way to the latrine when the plane hit; everyone else in the ACSIM office was killed.

"As Brian was engulfed in diesel and flames, his polyester Class Bs were burned to his skin. The only thing that saved him as he crawled to the courtyard, was that he was old school. He wore the old black leather shoes, not the plastic corfram ones. His feet were the only place on his body not burned, so that's where the IVs were stuck," Burns said.

One hundred and eighty four people were killed at the Pentagon that day; hundreds more injured. The toll could have been much higher, according to Burns. "The Pentagon wall that was hit had been recently rebuilt with blast-proof windows, reinforced steel versus pure concrete and sprinkler systems. The structure actually stood for more than half an hour which enabled many to escape," he said.

The terrorist attacks of Sept. 11, Burns said, changed the way the U.S. military does business. "We're no longer fighting a Cold War. The Global War on Terror -- now overseas contingency operations -- is like a dimmer switch. It flares up, it settles down. And, the Army used to 'live to train.' Now we train to live so our Soldiers survive a combat deployment."

So today, while the chapel bells chime their lonely refrain, Burns will reflect on his thankfulness for surviving that day -- and the guilt he feels at walking away while so many others lost their lives and limbs.

Several weeks ago Burns made a trip to Walter Reed Army Hospital to visit a wounded Soldier. Afterward, he stopped at the Pentagon Memorial.

"I sat on one of the 184 benches situated there and offered some prayers for those we lost. They gave all of their days for our tomorrows."

Fort Polk family member Miguel Vera was in law enforcement in New York City when the planes struck.

"I was in Queens campaigning as a union delegate when I heard the news that a plane had hit the first tower. We thought it was an accident, but after the second hit, we knew it was something more. We headed back to the city, and it was really hard to get in. Everyone was trying to get out."

As a first responder assigned to guard the perimeter, Vera was witness to haunting, horrendous scenes of a hellish, surreal landscape. "On the first day, the rubble was so hot that you could only work for about 15 minutes before you had to change clothes. You just knew that no survivors were going to be walking out. I have never seen anything like it. Can you imagine seeing a skyline that no longer contained those huge, familiar buildings'"

After several days, Vera donned his National Guard uniform to lead organization efforts in a warehouse laden with an ever-growing number of donations and Federal Emergency Management Agency equipment. After the horror of those first few days, leaving the "front lines" was a relief, Vera said.

"The warehouse was the central location for all sorts of merchandise, from flowers to generators. There had to be about 50,000 boxes there. It was a daunting task to sort through it all, but after a little more than a week, we had straightened up. It was one of my proudest moments. I felt like I had done my part."

As the chapel bells toll, Vera will remember many things about Ground Zero. He will remember the first responder, a Vietnam vet, who cracked under the pressure of digging through a seemingly never-ending mountain of rubble. He will remember the trailers filled with body parts, more than 80,000 of them. He will remember a leg leaning on a piece of metal, a woman's leg he knew, because it wore a woman's shoe. But most of all, Vera said, he will remember the good in man, the good he saw taking place at Ground Zero during clean-up when people of all cultures, creeds and backgrounds did what they could.

So on this day the nation pauses to remember and reflect on what happened Sept. 11, 2001. And throughout the country, bells will toll. Even as the years progress, almost every American will remember where they were, what they were doing that day. Those shared memories unite America. They hang frozen in time, moments suspended with a crisp clarity that will not fade.

Social Sharing